Book

50 Chapters

Abstract

John W. Welch Notes

The text in Alma 23:1 picks up where Alma 22:27 had left off, with the remarkable extension of royal privileges to the sons of Mosiah granted by King Lamoni’s father. It is not surprising that he would extend this political, diplomatic privilege. Ambassadors and envoys were typically granted regal immunities and protections in the ancient world, since otherwise international communication and diplomacy would have been impossible. But more than that, Lamoni’s father had a special interest in protecting his missionary, Aaron, and also the other three sons, since he had made a special personal appearance in Middoni to free the four brothers from prison.

When Ammon and Lamoni returned to his land of Ishmael, Lamoni declared that his people “were free” and independent from his father’s rule (21:21), and Lamoni granted them “the liberty of worshiping the Lord their God according to their desires” (21:22).

Meanwhile, Lamoni’s father was converted by Aaron, with Omner and Himni and their companions, who accompanied him back to the land of Nephi (22:1). But recognizing “the hardness of the hearts of the people” and even the queen, who were ready to kill Aaron (22:21–22), Lamoni’s father “sent a proclamation “throughout all the land, amongst all his people who were in all his land, who were in all the regions round about” (22:27), which was a grant of absolute safe conduct for these four sons of Mosiah and their brethren. Freedom of religion was not granted by this decree, as it had been by King Lamoni in the land of Ishmael, but at least the missionaries were absolutely protected and granted free access into homes, temples, and holy spaces (23:2–3).

Apparently, the lands of Amulon, Helam, and Jerusalem, were outside the jurisdiction of King Lamoni, and so, even though the converts of Ammon (the Anti-Nephi-Lehis) will be butchered in those lands, Ammon himself and his brothers were protected there by this proclamation of Lamoni’s father. The four sons were never threatened or harmed. Indeed, when they finally meet up again with Alma, Ammon rejoices that they had been able to travel from “house to house” and also to teach in “their temples and their synagogues” (26:28–29). Although they had been spit upon, smitten on the cheeks, had stones thrown at them, and were cast into prison (26:29), they were apparently protected to a certain degree by this king’s royal proclamation.

All of this explains why the geographical explanation in Alma 22:27–34 was included in this text. While people studying the geography of the lands of the Book of Mormon rightly see this geographical aside as the best roadmap we have been given for the lands around Zarahemla, it is clear that its purpose here is to explain just one thing, namely the extent of the territory covered by the royal edict of Lamoni’s father, who controlled only “the land of Nephi and the wilderness round about” (22:34). But beyond that, except to some extent in the east (22:29), the Lamanites were “hemmed in” and had “no more possession on the north” (22:33), neither “on the west” (22:28), nor in “all the northern parts” (22:29–32).

The purpose of this geographical information was not to connect Alma with the Sons of Mosiah. None of Alma’s Nephite lands, such as Gideon, Melek, Sidom, Ammonihah, Jershon, or Antionum are mentioned here. Nor are the interior regions of the land of Nephi mentioned that were controlled by the king of the Lamanites. If this geographical statement had been made by Ammon or Aaron, one would have expected places such as the lands of Ishmael, Jerusalem, Ani-Anti, Middoni, Midian, Amulon, and Helam to have been mentioned. Mormon’s interests, however, were much more focused on the separation between the greater land northward and the political configuration of the land southward (22:30–32), and thus it makes sense that he would have included only this information, exclusively from his perspective, for the general benefit of his ultimate readers many years to come.

John L. Sorenson, The Geography of Book of Mormon Events: A Source Book, Revised Edition (Provo: FARMS, 1992), 242–248.

Joseph L. Allen & Blake J. Allen, Exploring the Lands of the Book of Mormon, Revised Edition (American Fork: Covenant, 2011), 402–416; new edition, with Sheryl Lee Wilson, Promised Place—Precious People (2020), 79.

Joe V. Andersen, F. Richard Hauck, Stanford Stoddard Smith, Ted Dee Stoddard, Lenard C. Brunsdale, A Compelling Geograpnhic Model of the Book of Mormon (Mesa, AZ: JVA Publishing, 2018), Appendix 7, 231–242.

It is also well to pause and think about the fact that these four missionaries were not only the sons of Mosiah, but also were the grandsons of King Benjamin. Ammon dutifully gives his father Mosiah credit for putting into practice in Zarahemla the law that there should not be “any slaves among them” (Alma 27:9), but it was his grandfather, Benjamin, who had announced that new law among all the people in the land of Zarahemla (Mosiah 2:13). Thus, it is noteworthy that the last words in the proclamation that the Lamanite king sent out in Alma 23:3 repeated almost exactly the very same five public law prohibitions found in King Benjamin’s speech in Mosiah 2:13, namely that people should not (1) murder, (2) plunder, (3) steal, (4) commit adultery, or (5) any manner of wickedness. These laws (1) protect life, (2) prohibit violence and lawlessness, (3) secure property against secret taking, (4) respect marriage and family, and (5) honor religion and righteousness.

The Lamanite king likely gleaned this material from Benjamin’s four missionary grandsons. When they preached the gospel, they opened the records and shared them with the people. Similarly, when the first Ammon and his brethren had compared their records with Zeniff and Noah down to the time of Limhi in the city of Nephi, they also opened up and shared the speech of Benjamin (see Mosiah 8:3). It is clear they all carried King Benjamin’s speech with them as one of their main scriptures. Upon his conversion, Lamoni’s father no doubt was taught and readily agreed that these five basic rules of public order had been wisely revealed by King Benjamin, that they had worked well for Nephite society, and so they should work well for people in the land of Nephi as well.

One of the implications here is that these Lamanite converts learned the Nephite heritage well. They took the new knowledge they had embraced very seriously. This can be seen when Ammon and Aaron converted these royal households and then entire lands. When the people of Ammon finally moved to Zarahemla, they integrated quickly and readily into the Nephite world. Regardless of one’s background, all are welcome into the fold of God, as Ammon rejoiced (26:4). People can change. No doubt many of us have witnessed how converts to the gospel of Jesus Christ can end up showing greater faith and devotion than those who have grown up in the Church.

In addition to the use of Benjamin’s words, there is another interesting feature of this decree. The king said that it should go:

Throughout the land unto his people, that the word of God might have no obstruction, but that it might go forth throughout all the land, that his people might be convinced concerning the wicked traditions of their fathers, and that they might be convinced that they were all brethren (Alma 23:3).

In that last part of his decree, he emphasized that everyone within his land were all brothers. While there were many different types of people living there—Lamanites, Lemuelites, Ishmaelites, Amulonites, etc.—he wanted to overcome tribal tension, clannish exclusivity, and social segregation by instilling a sense of brotherhood. The Gospel can do that.

Does the restored gospel hold the potential for convincing everybody in the world today, men everywhere, that they are all brothers? It most certainly does. Joseph Smith once said that “Fri[e]ndship…is the gr[a]nd fundamental prniple [principle] of Mormonism, to revolution[ize] [and] civilize the world.— pour forth love” (Joseph Smith, Journal, 23 July 1843, Book 3, 15 July 1843–29 February 1844, Journals 3:59–185, available online at Josephsmithpapers.org). The restored gospel is the greatest revolutionary power the world has even known, because it can cause all men to become friends with each other. It is remarkable that he made that revolutionary statement only 50 years after the American Revolution and 35 years after the French Revolution. World peace and harmony certainly would qualify as the greatest change upon the face of the earth and in every land in the world today. Joseph had a lot to say about friendship, and how he hoped to transform hearts to create friendship among all people; and King Lamoni and his father, in being converted through the wonderful doctrines of King Benjamin’s speech and the testimonies of the sons of Mosiah, wanted to make that happen. However, one royal decree did not turn everyone into good friends.

The Restored Gospel does an amazing job of successfully integrating people and peoples. Our wards and units are defined by geographic boundaries and not by social or economic choice. Members of many other churches may choose which church, priest, or pastor they want to follow, and as a result, people select the ones that they are most comfortable with. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is rare, if not totally unique in the world, in that it requires church members to belong to a ward and stake based on where they live and to regard everyone there as brothers and sisters. Imagine if this principle, of all being family, were implemented on a massive political and social scale. That would indeed be nothing short of a daring revolution that would civilize the entire world.

Seven seems to be an important number in the report of Ammon and the rejoicing of Alma, as we will see below. Here it is recorded that the sons of Mosiah converted Lamanites in seven lands or city-states: the lands of Ishmael, Middoni, Nephi, Shilom (meaning “peace”), Shemlon, Lemuel, and Shimnilom. The text doesn’t say there were seven, but they count up to that, “and these are they that laid down the weapons of their rebellion, yea, all their weapons of war, and they were all Lamanites (23:13).

Of course, there are seven churches found in the Book of Revelation, along with seven angels, seven trumpets, and seven seals; and the number seven is all over the place in the priestly book of Leviticus. When Alma the Elder came to the Land of Zarahemla, he received permission from King Mosiah and opened seven churches in Zarahemla (Mosiah 25:23). I wonder if the four sons of Mosiah ever pondered about having converted people in seven cities. Perhaps they saw these as doing seven-fold penance for the damage they had done to the church in the land of Zarahemla. In the process they also learned that God cared just as much about the Lamanites as he did about the people in Zarahemla. This equal, ecclesiastical setting offer yet again a good message for us today throughout the world.

The one main barrier that the sons of Mosiah ran into was the Amalekites: “And the Amalekites were not converted, save only one” and “neither were any of the Amulonites” (23:14). They become problems for the Nephite world. The Amulonites were the successors of the priests of Noah. The Amalekites are unidentified. They were not descendants of Laman or Lemuel. They may have been Ishmaelites. They may have been Zoramites, or perhaps Mulekites. Or they could have been complete outsiders.

One possibility is that they are related to the Amlicites. Because in the original manuscript of the Book of Mormon, the words Amalekite and Amlicite were spelled four or five different ways, we do not know whether they represented different groups. It is possible that Oliver Cowdery did not know how to spell this term every time the word came up. It is also possible that the words were pronounced differently depending on the ancient dialect. The history indicates that sometimes when Joseph Smith came across a new name in the Book of Mormon translation, he would spell it out. There is also manuscript evidence of in-process corrections of the spelling of some words. This means a word would be written, but then it would be crossed out and spelled again in line—not above the line, but right after it. However, that would only happen the first time it was spelled. And then Joseph expected Oliver to remember how it was spelled, which apparently did not always happen.

Book of Mormon Central, “How Were the Amlicites and Amalekites Related? (Alma 2:11),” KnoWhy 109 (March 27, 2016).

Royal Skousen, Analysis of Textual Variants of the Book of Mormon: Part Three, Mosiah 17–Alma 20 (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2006), 1605–1609.

J. Christopher Conkling, “Alma’s Enemies: The Case of the Lamanites, Amlicites, and Mysterious Amalekites,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 14, no. 1 (2005): 108–117, 130–132.

We are told in Mosiah 23:14 that one Amalekite was converted. Why might this have been mentioned? They worked so hard to convert these people by preaching in the synagogues of the Amalekites, and yet they came away empty except for this one.

Missionaries, take hope wherever you are, the worth of souls is great, even if it be only one soul! (D&C 18:15). It would have been easy for the account of the four sons to have said that they worked real hard but did not have much success among the Amalekites. But even one soul was worth mentioning in the record. Think of other stories in the Book of Mormon where just one was converted. Alma the Elder was the only convert of Abinadi in the courts of Noah. Was he worth something? In the city of Ammonihah, Amulek was initially the only one who listened to Alma, and what a convert and ally he became! Together, Amulek and Alma converted only Zeezrom. As far as we know, the others were driven out or killed. At times, missionaries in the Book of Mormon converted thousands, but that is not always the case. It begins so often with just one, and that one is important.

President Bateman gave a talk in which he reminded us that the Savior invited the people at the temple in Bountiful to “Arise and come forth unto me, that ye may thrust your hands into my side, and . . . feel the prints of the nails in my hands and . . . feet, that ye may know that I am the God of Israel, and the God of the whole earth, and have been slain for the sins of the world” (3 Nephi 11:14). President Bateman went on to say:

The record indicates that the multitude went forth “one by one until they had all gone forth, and did see with their eyes and did feel with their hands, and did know of a surety” (3 Nephi 11:15; emphasis added). Although the multitude totaled 2,500 souls, the record states that “all of them did see and hear, every man for himself” (3 Nephi 17:25). If each person were given 15 seconds to approach the resurrected Lord, thrust their hand into his side, and feel the prints of the nails, more than 10 hours would be required to complete the process.

That is the way the gospel works—one at a time. We all go through the same process. There are no missed steps for anyone.

Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Jesus Minister to the People One by One? (3 Nephi 17:21),” KnoWhy 209 (October 14, 2016).

Merrill J. Bateman, “One by One,” BYU Speeches (September 9, 1997).

In this setting, the king over the greater land of Nephi wanted to have a name by which all of the converts could be called. He and Aaron settled on the name “Anti-Nephi-Lehies” (23:16). This name embraces the land of Nephi, the common ancestry back to Lehi, and the idea that these converts are now a part of the Nephites.

There are a good number of names that begin with the prefix anti. Antionum, Antipas, Antipus, antion, and then of course there is the Anti-Christ. The anti in anti-Christ means something completely different from the usage here. Anti-Christ, it means against Christ. Transliterated words such as Antionum, are Nephite words with Nephite syllables.

We do not really know what anti means. That is one of the things I want to look up in the Nephite dictionary when we finally get it. This name may simply have designated “descendants of Lehi who are not descendants of Nephi,” or as we might say “non-Nephite Lehites.” But a better possibility is that it comes from the Egyptian nty, which means “the one who,” or “of,” or “part of.” In other words, these people wanted to be known as descendants of Lehi who were part of the Nephite religious order.

Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Converted Lamanites Call Themselves Anti-Nephi-Lehies? (Alma 23:17),” KnoWhy 131 (June 28, 2016).

“Anti-Nephi-Lehi,” Book of Mormon Onomasticon.

The king’s proclamation did not succeed in all ways, at least it did not please the Amulonites and the Amalekites, who opposed the king entirely and openly. In addition, the king’s proclamation was quickly ignored, because he passed the kingship to his son before he died (24:3). Whenever there was a new king, there was instant instability. Immediately there were people who wanted to attack those who had converted. Sadly, the Anti-Nephi-Lehies had taken an oath that they would not take up arms ever again; they would rather die than use their weapons. Since, as the text says, they had buried the weapons “deep in the earth” (24:17), they would have had to dig them out of the ground. Their king commanded them not to make any preparations for war (24:6), and more than a thousand of them died rather than violate their oath.

The essence of the words of the king of these converts is found in Alma 24:7–16. His words of assurance and reinforcement are a model of solidifying the repentance process. The story of the Ammonites offers great instructions on how we too can best go about the repentance process.

They began by being thankful for God’s goodness, for his messengers, for softening their hearts, and for taking away their guilt, no matter how great (24:7, 8, 9, 10). They then sought to distance themselves from everything they might use, such as their swords, to commit sin again. If God will take away our stains, we must not repeat the sin (24:12–15). Only Christ’s blood can overpower the bloodstains of our sins (24:13). This gives vibrant meaning to the idea of “blood for blood,” which will remain bright “unto future generations” (24:14).

These converts knew the importance of standing together in unity. The people all agreed with their leader. Together they came forth “vouching and covenanting with God” that their repentance was indelible. They then began to work hard together with their hands. They changed from being idolatrous (24:18). They firmly accepted the truth both verbally and practically—they really applied the gospel to themselves. That is an important example for us when we repent and want to change. Change is usually not easy. We cannot expect to repent and not have to expend effort. Doing it together is best.

They associated with good people. They became friendly with the Nephites, and that would really have helped their repentance. If we continue running with the wrong crowd, that does not facilitate our progress either.

Stunningly, they all remained committed as a group. This appears to be an ordinance that was not conducted one by one; they were all willing as a group to pledge to honor this commitment together. There was strength in numbers here. Perhaps, in the repentance process, we can become stronger in overcoming problems as communities if we are all committed to the change.

They all buried their weapons. They found whatever the implement of the sin was, and buried it deep within the ground. Maybe we could look for a symbol of our repentance too. I do not know what your implements might be, but, if you struggle with the Word of Wisdom, you may consider confiscating whatever food or drug tempts you. Whatever it might be, bury it deep and get it out of your way.

They faced the challenges and oppositions together, whatever the costs. Many were killed rather than take up arms again. The result was horrific, but the effect was more powerful than anything else they could have done, and many of their attackers came over to their side.

This brief section appears to have been inserted by Mormon to show how the wicked will not support each other, will turn against each other to everyone’s harm, and how the Lord’s prophecies will be fulfilled.

Some of those who had been violently opposed to the Anti-Nephi-Lehies were pure literal Lamanites, “actual descendants of Laman and Lemuel” (24:29), and they became very upset that their supposed allies had used them to kill so many of their own Lamanite brethren (24:28). Most of the leaders who had led the attacks on the Anti-Nephi-Lehies were, in fact, “after the order of Nehors” (24:28), who were Nephites, or were “the seed of Amulon,” who were priests of Noah, also a Nephite (25:4). The Lamanites, now becoming angry because those people had “slain their [Lamanite] brethren” (25:1), turned their vengeance “upon the Nephites” (25:1). In particular, they chose as their target “the land of Ammonihah,” not only because it was close (being near the head of the River Sidon, including the cities of Melek, Sidom and Ammonihah), but also because Ammonihah was the headquarters of the Order of Nehors. These Lamanites “fell upon the people in the land of Ammonihah and destroyed them” (25:1), leaving it as the “Desolation of Nehors” reported back in Alma 16:9–11. This explains the not so obvious reasons why the Lamanites attacked the borders of the land of Zarahemla and destroyed the city of Ammonihah (25:1–2).

While few details are given, among those who attacked this Nephite territory were both Lamanites, many of whom were driven and slain (25:3), and also “almost all the seed of Amulon,” and they were slain by the Nephties (25:4). The remainder of this Lamanite force, including “the remnant of the children of Amulon,” then fled into the east wilderness (not wanting to return to the land of Nephi). Those Amulonites then usurped “power and authority over the Lamanites” (25:5) and put to death any Lamanites who began to disbelieve the traditions of the Lamanites and wanted defect over to the side of the Nephites. But those additional martyrdoms caused “contention in the wilderness” (25:8), and those last remaining Amulonites were then hunted and killed, thus fulfilling the prophecies of Abinadi (25:7–12).

Many of these Lamanites return home and come over into the land of Ishmael, where they also bury their weapons of war, join the people of Lamoni, Ammon, and the sons of Mosiah. They keep the law, statutes, and ordinances according to the law of Moses, knowing that it was a type of Christ’s coming. “They did retain a hope through faith, unto eternal salvation.”

With one brief interruption from Aaron who thinks that Ammon’s joy carries him “away unto boasting” (26:10), this entire chapter gives us “the words of Ammon to his brethren.” He expresses amazement at the great blessings the Lord had granted them during their fourteen year mission, things they could not have imagined when they left their home and royal stations in Zarahemla. His reminiscence is very detailed:

In every respect, the rejoicing of Ammon in Alma 26 acknowledges the fulfillment of the blessings given to the sons of Mosiah at the outset of their mission. Thus, Aaron may have been a little too quick to quick in objecting to Ammon’s exuberance. He rejoiced as he glorified God, not himself (26:11–12, 35–36). We might well wonder if we rejoice in Ammon’s way often enough today.

In reading Ammon’s words, an interesting personal thread also runs through his exuberant reverie, namely the number of times his words echo the words of Alma, as he described the appearance of the angel to him and the four sons of Mosiah reported in Mosiah 27 or other words of Alma about their conversion. Take note of the following distinct verbal allusions:

Remember also that these sons of Mosiah were grandsons of Benjamin. Thus, be on the lookout for places in Ammon’s rejoicing that are drawn from King Benjamin’s foundational speech. For example:

Finally, notice that the word “joy” appears in Ammon’s ecstatic reflection seven times (“my joy,” 26:11; “with joy,” 11; “our joy,” 16; “our joy,” 30; “my joy,” 35; “my joy,” 36; “my joy,” 37).

Another seven-fold expression of complete joy will show up again in Alma 27:17–19, and yet a third time in Alma 29:5, 9, 10, 13, 14, 14, 16.

These triple expressions of joy to the seventh power, along with the many precise word choices in these deeply personal chapters seem far too literarily purposeful and symbolically meaningful to be accidental or unintentional.

Corbin Volluz, “A Study in Seven: Hebrew Numerology in the Book of Mormon,” BYU Studies Quarterly 53, no. 2 (2014): 57–83.

When the Lamanites returned, having gone on a campaign against the Nephites in the land of Ammonihah (see 25:13; 27:1), they found that the Amalekites were very angry and they begin to destroy the Anti-Nephi-Lehies. Ammon and his people decide to ask the Lord what to do. Ammon was told, “Get this people out of this land” (27:12). He gets permission from the king of the Lamanites to do this, and he takes his converts to the wilderness between the land of Nephi and the land of Zarahemla (27:14). There he leaves the people, while he and his brothers return to Zarahemla to see if they can negotiate terms on which these refugees can be given a place.

One can easily imagine why these righteous Ammonites, however, would have rightly been concerned about relocating to the land of Zarahemla. They would be leaving their homeland, their culture, their language, their climate, their normal occupations, going into the land of their traditional enemies, into a new religious and cultural mix, and facing many other challenges. Immigrants and refugees today can certainly relate well to the challenges that these recent converts must have faced. But they went, seeking safety, protection, the free exercise of religion, and to follow the instruction of the Lord to emigrate to a new land of promise.

On their way to the city of Zarahemla to consult with people in Zarahemla, the sons of Mosiah meet Alma, who was on his way from Gideon to Manti (Alma 17:1; see also Alma 16:15). This chance encounter produced this second seven-fold expression of joy (27:17–19):

Apparently without much difficulty, these five returned to Alma’s house and obtained permission of the Chief Judge, who without further consultation, issued a proclamation admitting the people of Anti-Nephi-Lehi into the Nephite nation. The voice of the people then approved the transfer of the land of Jershon to these people as a land of inheritance (27:22). They agreed to protect these people because of their oath not to take up arms, provided they would agree to give “a portion of their substance to assist” in maintaining the Nephite armies (27:24), a kind of a tax.

The immigrants happily agreed, were numbered equally among the people, were zealous toward God, honest in all things, and firm in the faith of Christ (27:27). About fifteen years later, these men and women will become the fathers and mothers of the boys who will become the stripling warriors of Helaman (in Alma 55–57).

Book of Mormon Central, “Why were the People of Ammon Exempted from Military Duty? (Alma 27:24),” KnoWhy 274 (February 13, 2017).

The Hebrew root word, Jerash (ירש) meant to inherit. When they put a nun (ן) at the end of a word, as in Jersh-on, it meant a place of—it is a toponymical suffix—and so the name Jershon literally means a place of inheritance, and it was given to them “for an inheritance” (27:22).

Book of Mormon Central, “Why Was Jershon Called a Land of Inheritance? (Alma 27:22).” KnoWhy 134 (July 1, 2016).

“Jershon,” Book of Mormon Onomasticon.

In this short chapter, a great battle—as had been threatened by the Amalekites, “because of their loss” of these people (27:2)—was fought. This battle was greater than any previous conflict in the land of Zarahemla (28:2). Evidently the Nephites were resolute in keeping their commitment to protect the Ammonites, who themselves were exempt from frontline duty. What made this war uniquely terrible? Several factors must have contributed. For one thing, the Zoramites had already defected from the central powers in Zarahemla and were building the city of Antionum in that area. They probably did not respond with their normal enthusiasm for the honors of battle. From a geo-political perspective, the lands of Jershon and Antionum must have been important to both the Nephites and the Lamanites. They were certainly willing to lose many lives in defending these neighboring lands, as “the bodies of many thousands” were given a proper burial and were “laid low in the earth,” while the bodies of many thousands were “mouldering in heaps upon the face of the earth,” presumably the bodies of the invaders that would not have been given anything but a token burial (28:11).

The war in this chapter occurred in the fifteenth year of the reign of the judges over the people of Nephi (28:7). Thus, Alma’s famous text in Alma 29 was written after an intense year of joy (with the return of the sons of Mosiah) and a devasting year (with the successful but very costly defense of Jershon). Thus, the beginning of the sixteen year of the reign of judges would have been the beginning of the forty-ninth year, the completing of the seventh sabbatical, since the time of King Benjamin’s speech. Such a sabbatical would have been a traditional time of great rest, of peace, of freeing the slaves, freeing of the debts, of rejoicing in the rest of the Lord. There had been thirty-three years from King Benjamin’s speech to the death of King Mosiah, and then these sixteen years more would equal forty-nine. King Benjamin’s speech itself may have occurred on some kind of sabbatical or jubilee occasion.

While a complete religious and literary analysis of Alma’s great introspective ode remains to be written, any careful reader comes away from this text inspired, sobered, instructed, happy, reminded, and fulfilled. In a manner that many readers can relate with, Alma expresses a devout wish, recognizes his limitations and God’s realities, poses introspective questions to himself, and most of all finds glorious joy in doing what God has commanded, remembering what God has done, sharing joy with others, and praying for their ultimate blessing.

But there is more going on here than that. Like a Bach fugue where every note has its place, every word in Alma’s composition is measured and counted. And like the text of a psalm that lends itself easily to singing, the opening lines of Alma 29 have been set unforgettably to music in one of the most successful musical settings ever given to any passage in the Book of Mormon.

While Alma 29 was certainly written as a part of the mourning and burials of the fallen soldiers who bravely defended the land of Jershon (see Alma 30:2), Alma’s words also made an exquisite sabbatical text. These words set the tone for the forty-ninth year, and also for the following fiftieth year, a jubilee year.

Whatever one calls Alma’s wonderful composition—a hymn, a psalm, a soliloquy, a high priestly benediction—it was the result of Alma’s fourteen years of service and struggle, his great joy at his reunion with the sons of Mosiah, but also his lamentation at the devastation of the war that has just ended.

It begins on a very high plane of confidence, recalling the voice of the Angel that had converted Alma and his four best friends. Alma must have still been pinching himself, realizing that his friends were still alive. For fourteen years, they had had no communication. They all could have been dead. They were thrown in jail. They were almost killed on several occasions. I suppose he had almost given up on ever seeing his friends again. What joy he would have had at their return!

And, notice again, that the word joy occurs in this chapter seven times (29:5, 9, 10, 13, 14, 14, 16). This is the third set in which the word joy is mentioned seven times. The number seven also has special significance in celebrating their 14 years apart. Ammon’s 7 mentions of the word joy plus Alma’s 7 equals 14.

The 49th year is also a sabbatical year, 7 x 7. So, the High Priest Alma is writing this at the beginning of the 49th year. This leads us to wonder if that year wasn’t recognized as the final sabbatical year before the Jubilee, which would be the 50th year from the time of King Benjamin’s speech, there having been 33 years from Benjamin’s Speech to the death of Mosiah and then these 16 years more. And notice that Alma 30:5 says that the 16th year of the Reign of Judges there was a year of peace, with no disturbances, and then that the 17th year was a year of “continual peace” (30:5). This is what the Sabbath and Sabbatical years were all about. Rest. Everything is peaceful. Even the land you let lie fallow. And what do you do the whole time? You celebrate, you rejoice. You remember the past. You praise God. You thank him for all the things that he has done. Just as Alma does in Alma 29.

Moreover, the Hebrew word jubel (יובל) means a trumpet. Alma 29:1 begins, “O that I were an angel and could speak with the voice of a jubel.” This is the word that the word Jubilee comes from. And at the beginning of each ritual year, there would also be a celebration of the Day of Atonement, a time for repentance as well as forgiveness leading to joy. And that theme follows next in Alma 29:2, as Alma wished that he could declare with a voice of thunder the need for repentance, the plan of redemption, that all would repent and come unto God, that there would be no more sorrow, and only happiness, on the face of all the earth. There could not be a better beginning for a Jubilee text than Alma 29:1–2, especially in the mind and heart of the High Priest over all the land.

When Alma, as the High Priest, begins this text with his wish to be able to “speak with the trump of God” (29:1), he invokes many high and holy contexts, for the blowing of the trumpets in ancient Israel was connected with many religious and political occasions. The “day of Yahweh” was a day for the sounding horns in joy over His victories. Horns would announce the commencement of an important feast-day, as required on the beginning of the New Year (Leviticus 23:24; Numbers 29:1), or the commencement of the Day of Atonement (Leviticus 25:9). Accompanying shouts for joy could occur in association with a royal jubilation, or when an individual experienced personal salvation, or to celebrate the making of a covenant by taking an oath, or in everyday life.

Alma 29 also ends with a high tone of personal reassurance, remembrance, praise and blessing, especially for those four brothers. I wonder if maybe this text might not be best understood as a high priestly prayer, a prayer of benediction in their behalf. All of this would fit perfectly, if this text was prepared in connection with a great sabbatical and jubilee moment.

In any event, it is hard to imagine any other person better suited to have composed this wonderful scripture, which also has some psalmodic qualities. For instance, Nephi’s psalm in 2 Nephi 4 was provoked, inspired, or brought about by the death of Lehi. Many psalms are expressions of lament. Likewise, it may have been the cumulation of Nephite and Lamanite deaths that made Alma so reflective and sober. Nephi, when he wrote his psalm was very vulnerable and going out into uncharted territory. I think Alma is also open here in recognizing his own vulnerability. With this writing, Alma began to reveal more about his worries, the fears that people had, the concerns about all the deaths. He could easily have kept this writing to himself, but we can be very grateful that he chose to keep it among his records and to share it with future generations, to let them know the deepest desires of his heart.

We can certainly learn many things about Alma’s character and personality from this beautiful spiritual expression.

For example, as always, Alma was not timid. He was a man of conviction. He wanted the people to repent and to come unto “our God.” He was not apologetic about his deepest wish. He knew what he knew, and he wanted people to come to his side.

Alma was not doubtful. He testified using the words “I know …” frequently. He knew whereof he spoke. He was a man of testimony.

He went on to say things like, “I know that God has granted man their agency, I know that there is a plan, that they should be able to choose.” His deepest motivation was “that there might not be more sorrow upon the face of the earth” (29:2). He was a compassionate man; he did not want these things for himself. The one wish of his heart was righteousness and benefits for all people.

He accepted God’s decrees. He was content with his assignment in life. He not only accepted but gloried in what he had been commanded to do.

He knows how to have joy: to be grateful for God’s mercies, to remember the deliverances (not the deaths), and to be happiest for the success of others.

Finally, Alma was a generous soul. The way he spoke of his joy is inspiring. His joy for other people took him even beyond his body to being overwhelmed (29:16). He was happy with his own success, but often when people have success in this competitive world, they hope that the competition does not succeed too much. That was not the way with Alma.

One can imagine that Alma realized the difficult choices made by the converts that Ammon brought back with him. Consider also the sacrifices of the four sons of Mosiah, who were gone for fourteen years as missionaries. There is never any mention anywhere in the Book of Mormon of any sons of Ammon, or of Aaron, Omner, or Himni, and there is not even an indication that they were ever married. How long they lived after their return is not recorded. Life expectancy was not very long in those days. They must have made some serious sacrifices in that matter, but Alma rejoiced for them even more than for himself. Such selflessness is characteristic of Alma. His soliloquy here is a genuine expression of his desire to bless others.

When Alma declared that he wanted to be an angel, he probably was not thinking about a random angel in the abstract. If you remember, Alma had first-hand experience with an angel. This angel cried repentance and spoke with the voice of thunder. The angel’s power knocked everybody down, and caused Alma to be physically afflicted for days. Alma was likely thinking that this was the kind of angel he wanted to be. An angel that had the power to bring about mighty repentance.

On an interesting note, Alma had been serving for the last eight years as the high priest of the temple. In the Israelite temple, angels appeared to God’s servants, such as Isaiah and Zacharias. Sometimes the angel was none other than the Lord himself. The angel of the Lord was often a name or euphemism for God himself appearing at the temple in the Holy of Holies. We do not know if Alma ever had angelic experiences in his service in the temple. Interestingly, Alma was not in the temple either time that the angel appeared to him. Alma knew that it was possible for an angel to appear outside of sacred precincts. His angelic experiences likely helped Alma recognize what it may have meant if he could have taught with angelic power: “And that I could have the wish of mine heart” (29:1).

What would you wish for if you could have the wish of your heart? We know what Alma’s heart was set on: wishing that he could bring repentance to every people. He was not some kind of an aristocratic, exclusivist leader, but rather wanted to embrace all people inclusively. That was unusual in the Israelite tradition because the high priest typically felt so strongly the need to protect his own purity. Jesus’ eating with the ordinary people, the sinners, the publicans, and the tax collectors, was concerning to people because that would have defiled him, in their minds. Even more so, the high priest needed to keep himself pure, but Alma did not approach his priesthood responsibility that way at all. He went out, even to do battle with Amlici and to call the unholy people in Ammonihah to repentance.

Book of Mormon Central, “Why Was Alma’s Wish Sinful? (Alma 29:3),” KnoWhy 137 (July 6, 2016).

Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Alma Wish to Speak “with the Trump of God”? (Alma 29:1),” KnoWhy 136 (July 5, 2016).

Dr. Glade Hunsaker, a former professor of English at BYU, commented on the beauty and appropriateness of the language as follows:

This beautiful soliloquy, as we sometimes call, it begins with, “O That I were an angel.” We take it so for granted. You notice that the “I”, the subject, does not seem to agree with were. Were seems to be plural, and there are very few folks today who realize that it is a singular subjunctive. We have PhDs in English that, unless they have studied German, French, or another language, have no clue what the subjunctive mood is. If this were really a product that had been put together in upstate New York by some flimsy folks, that piece would be lost to “O That I was an angel?” I would pick up my bag and leave. All the pieces are there. It is just exquisite.

While using the subjunctive “were” in this case may not have been the prevailing English grammatical usage in Joseph Smith’s day, it was not unknown then. Although Alma’s usage is unique in the Book of Mormon, it appears several times in the King James Bible. See 2 Samuel 15:4 (“Oh that I were made a judge”); Job 9:15, 21; Job 29:2 (“Oh that I were as in months past”); Psalms 50:12; 1 Corinthians 5:3; 2 Corinthians 13:2). Its linguistic touch in Alma 29 is compositionally elegant. Alma 29 is without a doubt a beautiful, powerful piece of writing. People can try to paraphrase the Book of Mormon, but to do so often diminishes its sophisticated beauty. In reading the writings of Alma, Mormon and Joseph Smith, the best presumption is that every phrase and every word is there for some very meaningful reason, and that reading technique certainly serves flawlessly well throughout Alma 29 in particular.

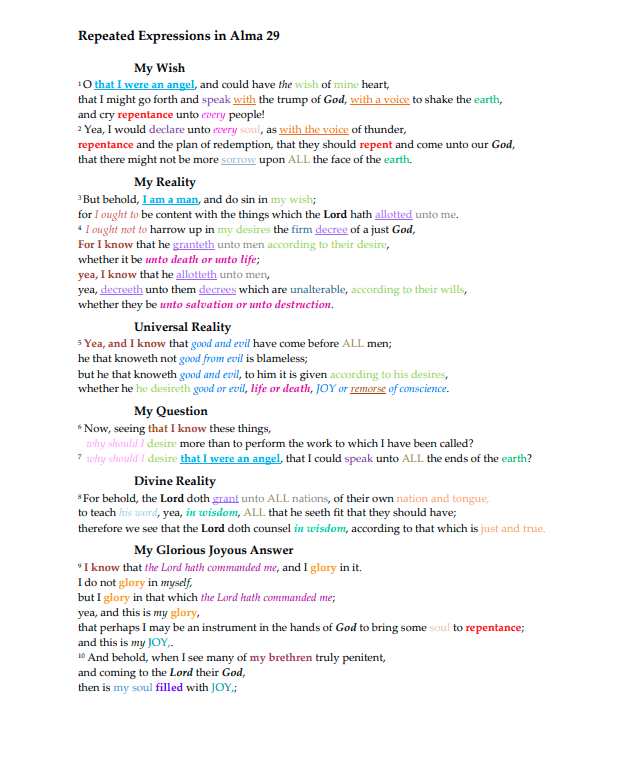

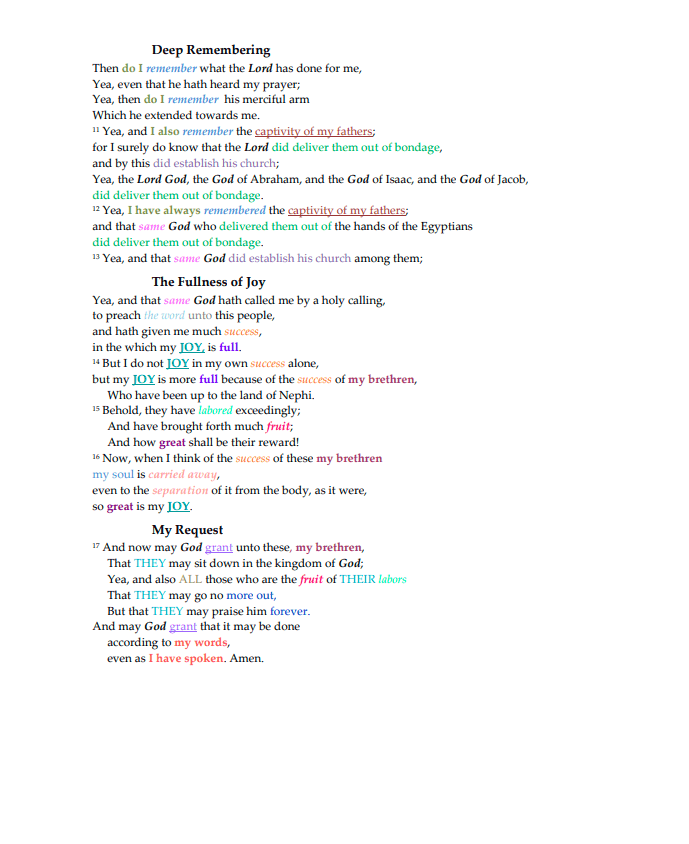

Having talked much about the wording of Alma 29, we are now prepared to read the words themselves. Hopefully these two final charts will help readers to see Alma’s masterpiece once again for the first time. However one reads this chapter, it always yields new insights. Here is a new arrangement of this text, with thematic subdivisions, with color coding to highlight the repetitions of individual words and phrases, with the text separated into poetic and parallelistic lines, and with chiastic inversions made apparent. This chart is followed by information that draws attention to word frequencies in Alma 29. Awareness of these textual characteristics and interactivities adds appreciation to the sophistication of this text at many levels.

Looking at words and phrases, the number of times each appears certainly does not appear to be random.

91 words appear in Alma 29 once and only once. This is a relatively high density in a text only 708 words long. Alma’s skill here gives solo emphasis to these singular terms, which in turn makes it more likely that the words used more than once were also intentionally chosen and counted.

Showing their diversity, the 91 words, in alphabetical order, are: Abraham, alone, always, am, amen, among, arm, away, because, before, blameless, body, calling, carried, coming, conscience, content, counsel, cry, declare, destruction, down, Egyptians, ends, exceedingly, extended, face, filled, firm, fit, forever, granteth, harrow, heard, heart, holy, how, instrument, Isaac, Jacob, kingdom, land, man, many, merciful, mine, myself, Nephi, no, O, our, penitent, perform, perhaps, plan, praise, prayer, preach, redemption, remorse, reward, salvation, separation, shake, shall, sin, sit, so, some, sorrow, surely, teach, than, there, therefore, think, those, thunder, tongue, towards, true, truly, trump, unalterable, upon, we, what, wills, words, work, would.

Reading these 91 words in the order of their appearance highlights the special power that each of these singular words has in the flow of this text: O, mine, heart, trump, shake, cry, would, declare, thunder, plan, redemption, our, there, sorrow, upon, face, am, man, sin, content, harrow, firm, granteth, unalterable, wills, salvation, destruction, before, blameless, remorse, conscience, than, perform, work, ends, tongue, teach, fit, therefore, we, counsel, true, myself, perhaps, instrument, some, many, truly, penitent, coming, filled, what, heard, prayer, merciful, arm, extended, towards, surely, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, always, Egyptians, among, holy, calling, preach, alone, because, land, Nephi, exceedingly, how, shall, reward, think, carried, away, separation, body, so, sit, down, kingdom, those, no, praise, forever, words, amen.

At least 27 words that appear twice, as doublets, in this text are color-coded as pairs in the chart of repeated expressions. These most often appear in synonymous or antithetical parallelisms, adding contrasts and drawing attention to nuances.

Only four words appear three times in this text, giving triadic solidarity to the central rejoicing of Alma, not only over the deliverance from bondage but also from sin:

Other triads, such as the God of Abraham / God of Isaac / God of Jacob, also appear (11).

Seven terms appear four times or in quatrains. Alma may have cast these fours in honor of his four friends, the four sons of Mosiah, his brethren, remembering the glory of their deliverance in the combat between good and evil:

The word “according to” appears five times:

Two words appear six times. They have to do with our desires, which make all the difference for all men, all nations, all that God wills, and all who bring forth good fruit, one of Alma’s main points:

Interestingly, four key words are given the special status of appearing seven times, emphasizing the completeness of revealed knowledge and of righteous joy, as well as the seven-fold holiness of the name of Jehovah (Lord):

1 O that I were an angel, and could have the wish of mine heart,

that I might go forth and speak with the trump of God, with a voice to shake the earth,

and cry repentance unto every people!

2 Yea, I would declare unto every soul, as with the voice of thunder,

repentance and the plan of redemption, that they should repent and come unto our God,

that there might not be more sorrow upon ALL the face of the earth.

3 But behold, I am a man, and do sin in my wish;

for I ought to be content with the things which the Lord hath allotted unto me.

4 I ought not to harrow up in my desires the firm decree of a just God,

For I know that he granteth unto men according to their desire,

whether it be unto death or unto life;

yea, I know that he allotteth unto men,

yea, decreeth unto them decrees which are unalterable, according to their wills,

whether they be unto salvation or unto destruction.

5 Yea, and I know that good and evil have come before ALL men;

he that knoweth not good from evil is blameless;

but he that knoweth good and evil, to him it is given according to his desires,

whether he he desireth good or evil, life or death, JOY or remorse of conscience.

6 Now, seeing that I know these things,

why should I desire more than to perform the work to which I have been called?

7 why should I desire that I were an angel, that I could speak unto ALL the ends of the earth?

8 For behold, the Lord doth grant unto ALL nations, of their own nation and tongue,

to teach his word, yea, in wisdom, ALL that he seeth fit that they should have;

therefore we see that the Lord doth counsel in wisdom, according to that which is just and true.

9 I know that the Lord hath commanded me, and I glory in it.

I do not glory in myself,

but I glory in that which the Lord hath commanded me;

yea, and this is my glory,

that perhaps I may be an instrument in the hands of God to bring some soul to repentance;

and this is my JOY,.

10 And behold, when I see many of my brethren truly penitent,

and coming to the Lord their God,

then is my soul filled with JOY,;

Then do I remember what the Lord has done for me,

Yea, even that he hath heard my prayer;

Yea, then do I remember his merciful arm

Which he extended towards me.

11 Yea, and I also remember the captivity of my fathers;

for I surely do know that the Lord did deliver them out of bondage,

and by this did establish his church;

Yea, the Lord God, the God of Abraham, and the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob,

did deliver them out of bondage.

12 Yea, I have always remembered the captivity of my fathers;

and that same God who delivered them out of the hands of the Egyptians

did deliver them out of bondage.

13 Yea, and that same God did establish his church among them;

Yea, and that same God hath called me by a holy calling,

to preach the word unto this people,

and hath given me much success,

in the which my JOY, is full.

14 But I do not JOY in my own success alone,

but my JOY is more full because of the success of my brethren,

Who have been up to the land of Nephi.

15 Behold, they have labored exceedingly;

And have brought forth much fruit;

And how great shall be their reward!

16 Now, when I think of the success of these my brethren

my soul is carried away,

even to the separation of it from the body, as it were,

so great is my JOY.

17 And now may God grant unto these, my brethren,

That THEY may sit down in the kingdom of God;

Yea, and also ALL those who are the fruit of THEIR labors

That THEY may go no more out,

But that THEY may praise him forever.

And may God grant that it may be done

according to my words,

even as I have spoken. Amen.

Book

50 Chapters

Items in the BMC Archive are made publicly available for non-commercial, private use. Inclusion within the BMC Archive does not imply endorsement. Items do not represent the official views of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or of Book of Mormon Central.