Book

50 Chapters

John W. Welch Notes

Alma chapter 13 is among my favorite chapters in all the Book of Mormon, if not all of scripture. Chapter 13 is the concluding second half of Alma’s patient words to the hostile Nehorites in the city of Ammonihah. Together, these profound chapters stand at the center of Alma’s horrific half-year experience there.

To see this discourse in its original historical context, here is a basic outline of “the words of Alma and also the words of Amulek” (Alma 9–14) and their subsequent outcomes (Alma 15–16):

A | Alma arrived in Ammonihah, warned them of their utter destruction, and was rejected (Alma 9). | |||

| B | Amulek received Alma into his house. Amulek converted and testified openly in Alma’s behalf (Alma 10). | ||

|

| C | Zeezrom tried to bribe Amulek, who withstood and silenced Zeezrom (Alma 11). | |

|

|

| D | Alma answered Zeezrom’s questions by explaining the creation, fall, God’s commandments, redemption, the resurrection, judgment, and the holy order of priests who help people repent and enter into God’s rest (Alma 12–13). |

|

| C | The people burned the women and children and imprisoned Alma and Amulek who escaped (Alma 14). | |

| B | Zeezrom was healed by Alma and Amulek in Sidom. They went to Alma’s house in Zarahemla (Alma 15). | ||

A | Ammonihah was utterly destroyed. Alma and Amulek were received throughout the land (Alma 16). | |||

At that point, the book of Alma reverts (in Alma 17) back to the account of the four sons of Mosiah beginning in the first year of the reign of the judges.

One of the main teachings of Nehor was that his priests should “become popular” and “ought not to labor with their hands” but “be supported by the people” (Alma 1:3). Alma the Elder and other Nephite leaders saw it otherwise: “the priests were not to depend upon the people for their support; but for their labor they were to receive the grace of God, that they might wax strong in the Spirit, having the knowledge of God, that they might teach with power and authority from God” (Mosiah 18:26). Alma’s understanding of the holy order of priesthood stood in sharp contrast to the Nehorite program.

Alma began his exposition on the priesthood where he had left off at the end of chapter 12. He said: “I would cite your minds forward to the time when the Lord God gave these commandments unto his children” (13:1, emphasis added). What does Alma mean by “these commandments”? This continues the discussion at the end of chapter 12, starting in verse 33: “But God did call on men, in the name of his Son … saying: If ye will repent, and harden not your hearts, then will I have mercy upon you, through mine Only Begotten Son.” So, the commandments to which Alma refers here include to the need for these people in Ammonihah to “repent” and to “harden not [their] hearts.” Since followers of Nehor believed that God “had redeemed all men,” they stood resolutely against the idea of needing to obey God’s commandments, let alone to repent for breaking them, in order to “have eternal life” (Alma 1:4).

Interestingly, here Alma added another point. We often think of man calling upon God in the name of God’s Son; but in this verse, God calls upon man “in the name of his Son”—emphasizing the role of the Savior as a mediator and intercessor going between God and mankind. The use and power of the Savior as mediator works both ways.

In addition, in Alma 13:2 Alma taught that God not only calls upon man in the name of his Son, but he ordains priests after the “order of his Son,” to function similarly, marking the way between God and man. The very nature of priesthood ordinations somehow symbolically demonstrated “in what manner to look forward to his Son for redemption” (Alma 13:2). Both Jesus and the priests use and model the way of conciliation and atonement. Of course, the Nehorites also denied that redemption required any particular action on the part of mankind (Alma 1:4). So, Alma provided a more detailed explanation, as follows.

First, men were called, and then some kind of initiatory preparation was given. This happened “from the foundation of the world, according to the foreknowledge of God” (13:3). After establishing the nature of these priesthood callings, Alma mentions that men were also “ordained unto the high priesthood of the holy order of God, to teach his commandments unto the children of men, that they also might enter into his rest” through their repentance (13:6, emphasis added).

In verse 11, we learn that this Nephite ordinance included some manner of sanctification. Men were made holy and were “sanctified,” and “their garments were washed white.” So, we know that this ordination made some use of important garments, and that they were cleansed through the blood of the Lamb. On the Day of Atonement every year, the ancient Israelites sacrificed lambs and other animals, and Nephites used that blood as a symbol of the blood of the Savior that would eventually be shed. That blood would then be used ritually and symbolically to sanctify the people and purify their garments.

Ritual sanctification is also closely tied to temple worship. We know that the Nephites built a temple after the manner of the Temple of Solomon, only not so grand (2 Nephi 5:16). We also know that the Temple of Solomon had three chambers: (1) the court of the priests, where the altar of sacrifice stood, then (2) the main inner room of the temple, and then, separated by the veil from that room, was (3) the Holy of Holies. From the outer court, the priests would go up a step into the second room, and then only the High Priest could step up again, this time through that final veil, into the third room. They were symbolically ascending, in a ritual model of the cosmos, as they progressed through the three levels within the Temple. Entering into the Holy of Holies represented entering into God’s rest, or entering into his presence.

The inner hall, the hekal in Solomon’s Temple, represented the days of creation as God worked through the veil, which represented the divider between heaven and earth. In the hall they had the menorah, which was the light—“let there be light”—on that day. There was, on the table, vegetables which represented the creation of organic elements. Animals were also represented. The different parts of the creation were all there.

This is typical of temples in the ancient world, which often tend to portray the Creation with symbols. In Egypt, all the temples had to do with the emergence of the first lotus, and the first bit of ground out of the primordial waters. All the Creation-related rituals that brought people like Horus back from the dead are answering the question, “How can we be raised again to life and never die again?” That is why the Egyptians mummified people. It was all connected with their understanding of the holy order of the priesthood, and eternal blessings and promises. In the Book of the Dead, people were being given certain things that they needed to say in order to pass by the angels and the sentinels that guard the way to eternal life. People who were not supposed to enter into the afterlife did not know how to do that if they had not had that blessing.

If you did not see hints of all of this in Alma chapters 12 and 13 the first time through, you now have a little orientation. Go back and read Alma’s words with some temple lenses on, and see what you make of it. Of course, reading these two chapters with priesthood and temple lenses on are not the only ways to read this richly rewarding text. I encourage you to read the two chapters several times in the next few days. Each time you read these chapters and verses, approach them from a different vantage point and look for something different:

1. Read these two chapters from Alma’s personal perspective. Why was he personally motivated to mention these particular things? How do these words relate to Alma’s conversion, previous speeches, needs, or experiences? What emotions and feelings does he communicate to you in these words? What does he hope will happen to all listeners as a result of this speech?

2. Then read these two chapters again and outline Alma’s main subjects and most emphatic words. How was this speech organized? Do all of its pieces work together logically, structurally, developmentally, and persuasively? Which words and phrases stand out most prominently to you?

3. What would it mean to hear these words through the ears of the people in Ammonihah? Which words might have stood out most prominently to that audience, especially if they were hearing some of this for the first time?

4. Then read these two chapters from Zeezrom’s perspective. Did Alma answer all the questions that Zeezrom had raised in Alma 12:7–8? How did these words contribute to Zeezrom’s further conversion and permanent change of heart?

5. And next, read these two chapters from Amulek’s perspective. Being a recent convert with a wicked background, Amulek might have taken special note of certain words and explanations that he would have heard with new and important meanings to him.

6. Then read this speech for yourself. Can you imagine yourself hearing Alma deliver this speech? What lessons might you learn personally from this text? What does it tell you about how you may know the mysteries of God, or about the purposes of this life, or about the Savior, or on what basis will we all be judged?

Book of Mormon Central, “How a Tangent About Foreordination Helps Explain Repentance (Alma 13:3),” KnoWhy 398 (January 11, 2018).

Book of Mormon Central, “What Did the Book of Mormon Teach Early Church Leaders about the Order and Offices of the Priesthood? (Alma 13:8),” KnoWhy 330 (June 23, 2017).

While I realize that sometimes words can appear in a text a random or insignificant number of times, I believe that more is going on here in Alma 12–13 than just something inadvertent or unintended. It would appear that Alma had probably given something like this speech more than once. After all, he had been dealing with the repercussions of the execution of Nehor for ten years. All this in Ammonihah occurred during the tenth year of the reign of judges (Alma 8:3; 15:19). The appearance of key words either seven, ten, or twelve times may well reflect, to some degree, careful composing of this text.

Hebrew numerology assigns symbolic meanings to certain numbers. The number twelve is believed to represent official judgment. For example, there were twelve apostles, twelve tribes, and twelve months of the year. It is an ordering number. Perhaps not coincidentally, there are five words that appear twelve times in this text. This feature would have been designed to enhance the holiness of the holy order of God, one of Alma’s main topics. Alma was only a man, but he was indicating, in a solemn, esoteric way, that his words were authorized by a governing force. The words he chose to repeat twelve times are noteworthy in this regard:

In addition, four words appear here ten times: men, high, Son, and hearts. Thus, men can be called to the high priesthood through the redemption of the Son if their hearts are pure. Alma points here to the underlying mystery, namely, that humans, as the children of God, can become perfect like their Father. And on the receiving end, Alma equally uses the injunction to “harden not” ten times. Ten is typically the number of perfection, and the high priesthood after the order of the Son of God is the medium of perfection.

Thirteen words make an appearance seven times each. They are: also, brethren, called, calling, faith, many, ordained, plan, prepared, priesthood, repent, repentance, and spoken. Seven was perhaps the most significant number in the Bible, representing spiritual perfection, completion, the seven days of creation, the seven-fold ceremonies throughout the book of Leviticus, the requirement to forgive seventy times seven (or forty-nine times ten), the seventh heaven mentioned by Paul, or the seven churches, candlesticks, lamps, seals, horns, eyes, trumpets, thunders, crowns, plagues, vials, and angels in the final completion of the history of the world in John’s Apocalypse. Accordingly, the fulfillment of the principles that Alma mentions seven times leads all people to spiritual completion.

Corbin Volluz, “A Study in Seven: Hebrew Numerology in the Book of Mormon,” BYU Studies Quarterly 53, no. 2 (2014): 57–83.

Diane E. Wirth, “Revisiting the Seven Lineages of the Book of Mormon and the Seven Tribes of Mesoamerica,” BYU Studies Quarterly 52, no. 4 (2013): 77–88.

John W. Welch, “The Number 24,” in Reexploring the Book of Mormon: A Decade of New Research, ed. John W. Welch (Provo and Salt Lake City, UT: FARMS and Deseret Book, 1992), 272–274.

John W. Welch, “Counting to Ten,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 12, no. 2 (2003): 42–57, 113–114.

To drive home the power of the true order of the priesthood of God in implementing the plan of salvation, Alma turned his attention next to Melchizedek and the Melchizedek Priesthood. Alma’s comprehension and articulation of the preeminence of Melchizedek is amazing in many ways, only a little of which we have time to highlight here.

When I was studying in a seminar conducted by James H. Charlesworth at Duke University in the early 1970s, I was very excited to learn about a recently published text from the Dead Sea Scrolls, named 11Q Melchizedek. As a Latter-day Saint, to whom the name Melchizedek is a more meaningful household word than among any other people in the world, it was impressive to me to find that certain Jews at Qumran, before the time of Christ, revered Melchizedek and expected him to lead his holy men to return to sweep the earth in God’s great cleansing and sanctifying of the world. This especially rang a bell for me because of Alma 13. There Alma also turns to Melchizedek as the greatest known holder of the high and holy priesthood after the order of the Son of God. I spent much of the next summer researching the history of Melchizedek among ancient Jews and Christians, and then presented a paper on that topic at the public celebration at BYU of Hugh Nibley’s 65th birthday on March 27, 1975. Finding even more to say on this subject, I continued to update and expanded this groundbreaking study in an article, “The Melchizedek Material in Alma 13:13–19,” which was included in the Hugh Nibley Festschrift, published in 1990. That study provided greater context and meaning about Melchizedek’s role in Alma 13 by analyzing various treatments of Melchizedek throughout history, not only in the Old Testament and Book of Mormon, but also in the Joseph Smith Translation of Genesis 14, in the Book of Jubilees, 2 Enoch, Qumran texts, Philo, and other ancient texts.

A great deal has been written about Melchizedek having been a type of Christ. There are even people who believe that Melchizedek, who appeared to Abraham and to whom Abraham paid tithing, was the angel of the Lord himself. We are in good company when we talk about the order of Melchizedek, which Alma equates with the Holy Order after the order of the Son of God. There is very important symbolism and material involved here.

For example, the name Melchizedek—Melchi-zedek—meant my king is righteous, or righteousness to the Lord. This name could easily be applied to Christ himself. Nevertheless, when Alma refers to Melchizedek, he is not referring to an angel. He is speaking of an actual king, the king of Salem, and a righteous king and a priest, of whom “none was greater” (Alma 13:19).

In verse 18, we read something very striking. Melchizedek was a king who exercised mighty faith. He received the office of the High Priesthood, but also, Melchizedek was working with wicked people. He had very wicked people to deal with just like Alma, and he converted them! Through teaching according to the Order of the High Priesthood with which he had been charged, he was able to preach repentance to these people, and as Alma said, “behold, they did repent.” That was the greatest miracle of them all!

Is there anything done by the power of the Priesthood that does not try, ultimately, to bring people to repentance? For example, baptism is for the remission of sins after repentance. The priesthood ordinance of blessing the Sacrament is for the renewal of baptism, that we might be forgiven of sins. The main, but not exclusive, use of Priesthood power is to bring about repentance in the lives of people, and that is how Alma would have hoped to be able to use his priesthood in Ammonihah.

At the end of his speech, Alma gently echoed the words of King Benjamin, gave comfort, and offered persuasion without condemnation and with love unfeigned (see 13:28). It is amazing that he could love such people that were truly his deepest and most entrenched enemies, knowing sadly that what he was doing would ultimately work to the condemnation of most of them. Nevertheless, as did that angel who stood before Alma and brought about his repentance and conversion, the greatest wish of his heart was that he could be an angel and do the same.

Book of Mormon Central, “Why Are Ordinances So Important? (Alma 13:16),” KnoWhy 296 (April 5, 2017).

Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Alma Talk about Melchizedek? (Alma 13:14),” KnoWhy 120 (June 13, 2016).

John W. Welch, “The Melchizedek Material in Alma 13:13–19,” in By Study and Also by Faith, 2 vols., edited by John M. Lundquist and Stephen D. Ricks (Salt Lake City and Provo, Utah: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1990), 2:238–272.

Jews, early Christians, Gnostics, and all kinds of people have been fascinated with Melchizedek. It is clear that he was an important person, but there is so little about him in Genesis 14 that it is very hard to know exactly what we are supposed to make of him. However, Alma seems to know more about Melchizedek than any of these other people. The Joseph Smith Translation builds on this subject even further, and now we have texts coming along like 2 Enoch and texts among the Dead Sea Scrolls, which may shed further light on Melchizedek’s legacy. And you can imagine my excitement in learning that people at Qumran believed that Melchizedek would come back, that he was a King and a High Priest, and he would stand as God’s right-hand-man carrying out the judgments of God.

Alma, however, did not see Melchizedek as a great warrior standing at the head of all his men. Alma did not have any soldiers to call on. What Alma really admired in Melchizedek was that Melchizedek had exercised mighty faith, and the people repented. Alma raised Melchizedek as an example to the people of Ammonihah, who also had “waxed strong in iniquity and abomination.” Alma was trying to help them recognize that repentance was still possible.

Melchizedek was also a solo operator, at least as far as the scriptures reveal. We know nothing about his father or about his lineage. He comes out into the battlefield and Abraham gives him tithes of all that he had. Here, Alma was doing some of the same things. He was operating alone, he had gone into Ammonihah armed with nothing but the Melchizedek Priesthood and the office of the High Priest after the Holy Order of God, which had been handed down from Enoch according to the Joseph Smith Translation and perhaps the version of Genesis on the plates of brass.

Melchizedek preached repentance, and the people repented. He used the power of the priesthood in such an effective way. Can you imagine Alma’s longing to do the same? A little later, Alma will exclaim, “O that I were an angel, and could have the wish of mine heart, that I might go forth and speak with the trump of God, with a voice to shake the earth, and cry repentance unto every people!” (Alma 29:1). In Alma 13, he is sort of saying, “O that I were Melchizedek! I know I have the same power as he held.” What a miracle it was to bring about repentance and establish peace in the land. That was why he was called the King of Peace, and why the scriptures make particular mention of him.

There is nothing greater that we can do with the priesthood than to bring people to repentance. That is what the power of the priesthood and every ordinance of the priesthood is for, whether it is baptism, the sacrament, or even marriage. Priesthood ordinance workers are working to help people to repent and turn their lives over to God. That was why Alma said, “And now is the time to repent. Now is your chance, people. If you will do this, you will have joy, not the Nehorite kind of rejoicing, but real joy.”

Verse 27 shows us the heart of Alma. Even under enormous pressure, even at the risk of his life, he spoke “from the inmost part of my heart, yea, with great anxiety, even unto pain.” Alma’s desire was traumatic enough that it appears he somehow already felt the coming pain—surely emotional and spiritual pain, but perhaps also some degree of physical pain. He declared, I wish that you “would hearken to my words, and cast off your sins, and not procrastinate the day of your repentance; But that ye would humble yourselves before the Lord and, call on his holy name, and watch and pray continually” (v. 27). And remember that the Nehorites refused to pray. Why should they pray if they did not believe in sin? If God was going to redeem them all anyway, as they thought, what was there to be asked for?

“Watch and pray,” Alma said, “that ye may not be tempted above that which ye can bear, and thus be led by the Holy Spirit, becoming humble, meek, submissive, patient, full of love and all long-suffering” (v. 28). At this point, Alma quotes King Benjamin. Why does he quote Benjamin at the very end of his last chance to speak to the people in Ammonihah? The ancestors of these Nehorites, their grandfathers, had been part of King Benjamin’s community, and Alma probably referred to Benjamin, hoping it would touch their hearts. It might have even occurred to them that they too could have “that mighty change” that King Benjamin had spoken of.

Then Alma offered the following: “Having faith on the Lord, having a hope that ye shall receive eternal life, having the love of God always in your hearts, that ye may be lifted up [resurrected] at the last day and enter into his rest” (v. 29). Alma followed that with an interesting thought, “And may the Lord grant unto you repentance” (v. 30, emphasis added). Have you ever thought of being granted repentance? Usually we think of repentance as something that we do, but here, Alma realized that the only way these people, and the only way any of us really repent, is when God grants us repentance, to soften our hearts and help us to be able to repent fully. This is the only place I know of where that concept appears in scripture—a wish that God will grant repentance. And there Alma ends.

These are wonderful chapters, as deep and profound as possible. We may wonder why he would throw such pearls before swine! As he addressed the most wicked people in his area of responsibility, he gave them the holiest and most sublime teachings that the High Priest possibly could give. He was giving them every opportunity, and he was being very directly responsive to their concerns and giving them every reason to turn around and repent and live their lives properly. It is a beautiful example of a faithful high priest.

Alma was successful with many of the ordinary men in Ammonihah, but apparently not with the priests. We do not know the composition of the group that he addressed, nor do we know where their chief judge fits here. Alma may have been doomed because so many people began to believe in him. The Nehorite leaders may have been alarmed as the people began to realize that for ten years, they had been told how bad Alma was. He had their hero, Nehor, executed. But after hearing Alma preach in person, some of them began to soften their hearts and repent.

Amulek and Zeezrom are both portrayed as real-life human beings. It is interesting how much can be pulled out of the record about these people to reconstruct their concerns, their backgrounds, and how they used language.

Zeezrom’s arguments were closely related to the Nehorite doctrines. What Nehor taught, especially according to Alma chapter 1, consistently fueled the arguments raised against Alma and Amulek and provided the political platform of the Nehorite people. It was not just a casual, “What-can-we-ask-him?” kind of thing. The questions posed to Alma were crucial for establishing the difference between the Nephite point of view and the Nehorite view. Alma and Amulek answered those questions in detail and with conviction. Zeezrom went along to Antionum after his conversion and healing, and that is an interesting part of his story. Zeezrom is initially thought of as one of the villains of the Book of Mormon, one of the bad people. But after his encounter with Alma and Amulek, he was totally converted. He reconsidered when he heard what they taught, and he became a powerful convert. What a hero he was. He became sick, he was healed, and then he went on to be a missionary companion to Alma.

We can also consider how Amulek must have felt after being told, “The blessing of the Lord shall rest upon thee and thy house” (Alma 10:7), yet he had to watch many righteous women and children in his community being burned to death. It does not say whether or not Amulek’s family were among the sufferers, but I think it was very likely that they were. For, after this incident and the healing of Zeezrom, Alma took Amulek home with him to the land of Zarahemla “and did administer unto him in his tribulations, and strengthened him in the Lord” (Alma 15:18), which certainly suggests that he had no family to go home to after he and Alma had been delivered from prison by an earthquake.

Amulek had said that Alma had blessed “my women and my children,” so one wonders who else was in Amulek’s family. He may have been taking care of his mother or aunts. Perhaps Amulek had responsibility for the widow of a deceased brother under the Levirate marriage system. Whatever the situation, he was responsible for a large household. Rising above his unimaginable losses and personal trials, he became Alma’s second witness in Ammonihah, and then became Alma’s main companion as he traveled for the rest of his missionary work.

In Alma 34, the Book of Mormon preserves another chapter of Amulek’s powerful testimony. Amulek’s experiences in Ammonihah help explain what he says to the Zoramite poor. There we have the strongest teaching in the Book of Mormon about the infinite power of Christ’s Atonement, the infinite ability of God to make things right. Amulek was the only person in the Book of Mormon who spoke of being embraced in the arms of God’s safety. He used the word safety and no one else does. That word must have meant a lot to him after the risks he had experienced.

Book of Mormon Central, “What Kind of Earthquake Caused the Prison Walls to Fall? (Alma 14:29),” KnoWhy 121 (June 14, 2016).

Who were the women and children that were burned? Do you think they were Amulek’s children? We know that Amulek’s women and children accepted Alma, and were among the believers. The text makes a point of that in Alma 10.

Why did Amulek not rush in to rescue his family from the fire? Well, both he and Alma were bound. They had been stripped, tied up, and starved for many days. He was in a very weakened and impossible condition. His heart must have ached as he watched. He asked Alma if they could do something miraculous to save them. He was hoping that Alma would call on the powers of Heaven to stop the suffering. Elijah was able to make a fire burn to destroy the priests of Baal. Why could not Alma make a fire stop burning? The Spirit constrained Alma, however, unlike when he was able to request the powers of Heaven to get them out of the prison. He recognized that “the Spirit constraineth me that I must not stretch forth mine hand” (Alma 14:11). Even a prophet cannot do something if the Spirit does not tell him it is right.

Alma explained that it was necessary for the event to reach its conclusion so a just judgment could come upon the people according to the hardness of their hearts. It is one of those awful events, but Amulek believed that in the end the women and children would be rewarded for their faithfulness.

God will typically not intervene to undo people’s choices. One wonders how our Heavenly Father, who loves and feels deeply, can bear to watch people using their agency. This event is strong testimony of the importance of the principle of agency and choice. As Captain Moroni wrote, “For the Lord suffereth the righteous to be slain that his justice and judgment may come upon the wicked; therefore ye need not suppose that the righteous are lost because they are slain; but behold, they do enter into the rest of the Lord their God” (Alma 60:13).

Consider that while Joseph Smith was healing people, his own children died, and Emma asked, “Why do you not raise our children? Why can you not heal our children?” He replied that it was the Lord’s will, not his. Think of Joseph and Hyrum in Carthage too. Even there, the jail walls did not come down with an earthquake as it did for Alma and Amulek, but Joseph knew, “I go as a lamb to the slaughter.” He did not expect those walls to come crashing down on the murderers who were invading that jail to kill him.

Often, such miracles happen to help those around, but the people in Ammonihah were beyond that kind of help. It may have strengthened Amulek when he and Alma were delivered by the power of God as the jail was opened.

Book of Mormon Central, “Why Does God Sometimes Allow His Saints to Be Martyred? (Alma 14:11),” KnoWhy 351 (August 11, 2017).

Alma and Amulek had been cast out of Ammonihah, and had fled to Sidom, where they encountered Zeezrom, who was sick. He, the former Nehorite accuser of Alma, was healed, converted, and baptized. He “began from that time forth to preach unto the people” (Alma 15:12). Eventually, Zeezrom served with Alma, two of his sons, and Amulek, in teaching the Zoramites in Antionum (Alma 31:6, 32).

This verse is one of many time markers in the Book of Mormon. It records the end of the tenth year of the reign of the judges. The text provides good information about some of the years in which Alma was the high priest during this time (Figure 1). We recall that he

Figure 1 John W. Welch, Greg Welch, "Alma as High Priest: Years 0–19 of the Reign of the Judges," in Charting the Book of Mormon, chart 25.

was the Chief Judge as well as the high priest for the first eight years of the Reign of Judges. He then gave up the judgment seat to focus on being the High Priest, and that happened in the ninth year. Alma immediately went to set the Church to rights, first in Zarahemla, then in Gideon. In Alma 8:2, we read, “And thus ended the ninth year of the Reign of the Judges over the people of Nephi,” and in 8:3, it is recorded that “… it came to pass in the commencement of the tenth year of the Reign of the Judges over the people of Nephi, that Alma departed from thence and took his journey over into the land of Melek.”

The tenth year began, then, as he is going to Melek to teach, but when did the tenth year end? It is recorded in this verse, Alma 15:19. “And thus ended the tenth year of the Reign of the Judges over the people of Nephi.” That is the end of chapter 15. They got out of prison in Ammonihah, and fled from there to the neighboring city of Sidom, where some of the persecuted male converts had fled.

Everything that was covered from the time Alma went to Melek, all the time in Ammonihah, all the horrifying events, and until Alma and Amulek returned to Alma’s home in Zarahemla, happened within one year. In fact, most of it happened within the second half of that year. A great deal of information is compressed here into a rather short time.

Apart from Ammonihah’s being destroyed, all in a single day, after the fifth day of the second month in the eleventh year (16:1, 10), the Nephites enjoyed a few years of peace until the Lamanites attacked again while chasing the converts of Ammon, whom Ammon had brought to the Land of Zarahemla. The Lamanites did not like that at all; they did not like losing all those people from their population. Thus, there was a bitter war in the fourteenth year of the reign of the judges. But then again, in the fifteenth and sixteenth years, peace returned. Notice also that the Zoramites in Antionum would also react bitterly when Alma and Amulek and other missionaries converted back and away many of the Zoramite working class.

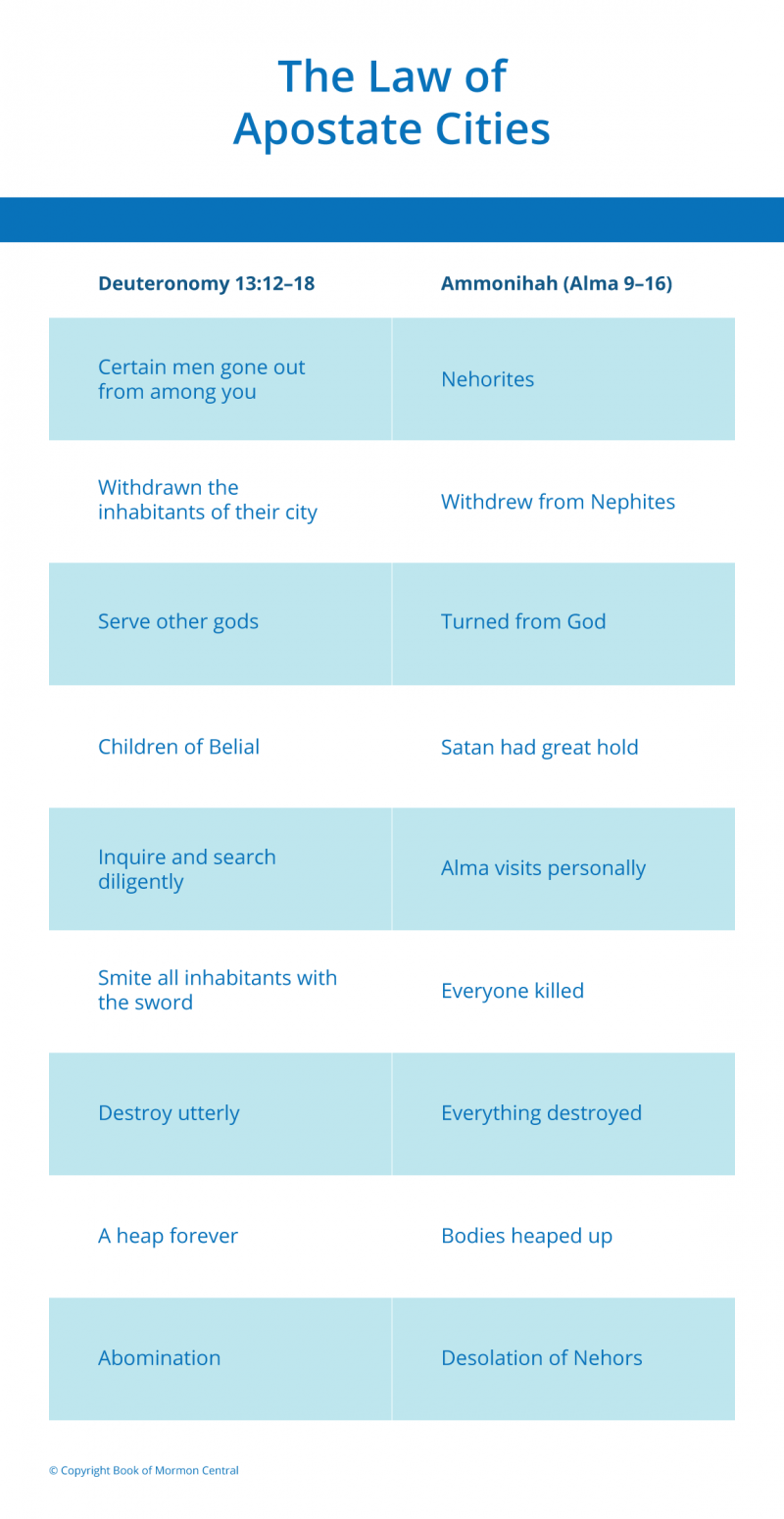

Ammonihah, on the other hand, was destroyed as prophesied and in accordance with the Law of Moses, which sets forth the procedures to be followed against an apostate city. Many details in the account of the trial of Alma and Amulek in Ammonihah are based solidly on legal provisions in the Law of Moses (Figure 2). In particular, it appears highly likely that Alma had Deuteronomy 13:12–17 specifically in mind in his accusation against the wicked people in the city of Ammonihah. That biblical text provided that an apostate city should be destroyed and anathematized in a particular way, involving a thorough investigation that produced clear evidence that the inhabitants of the city had withdrawn to serve other gods and had become “children of Belial” (or of Satan; for that detail, see Alma 8:9), followed by execution by the sword, leaving the city as “an heap for ever” (Deuteronomy 13:16). Of course, Alma no longer commanded the armies of the Nephites, and thus he did not have the military power at his disposal to carry out the destruction of an apostate city by his own physical means, but in due time, God brought the scourge of war upon the city of Ammonihah at the hands of an invading Lamanite army that would “slay the people and destroy the city” utterly, killing “every living soul” (Alma 16:2, 9). And indeed, it remained a “heap” for at least seven years (perhaps a ritual fallow sabbatical period), from the beginning of the eleventh year to the end of the nineteenth year (see Alma 16:1; 49:1).

Figure 2. John W. Welch and Greg Welch, "The Law of Apostate Cities," in Charting the Book of Mormon, chart 126.

John W. Welch, The Legal Cases in the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: BYU Press and Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2008), 238–271 discusses, among other things, the legal reasons why the women, children, and sacred books were burned, but not the men, who were banished (260–262); the legal significance of smiting on the cheek (263–266); the abusive imprisonment of Alma and Amulek (266–267); and the total infraction of all ten provisions of the code of judicial ethics in Exodus 23 (269–270), and thus articulating the justifications for the disastrous outcome in this case.

John W. Welch, “The Destruction of Ammonihah and the Law of Apostate Cities,” in Reexploring the Book of Mormon: A Decade of New Research, ed. John W. Welch (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1992), 176–179.

John W. Welch, “Law and War in the Book of Mormon,” in Warfare in the Book of Mormon, ed. Stephen Ricks and William Hamblin (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS., 1990), 91–95.

Here we have an interesting event, in which Zoram, the chief captain over the armies and his two assistant sons came to consult the prophet to find out where to go to reclaim captives. There is a famous precedent in which King Hezekiah consulted Isaiah to seek counsel to save Jerusalem. Isaiah prophesied that the Assyrians would be defeated and Sennacherib would die. Interestingly, King Hezekiah prayed for deliverance (2 Kings 19:1–7). It would be a wonderful way to run a country. Recall also that Nephi went to Lehi to ask where he could find food (1 Nephi 16:23).

Alma returned to preaching repentance, the whole point of learning the Gospel. Earlier, at the Waters of Mormon, Alma the Elder had taught specifically that they should “preach nothing save it were repentance and faith on the Lord, who had redeemed his people” (Mosiah 18:20). Here, Alma the Younger is still following his father’s guidance.

Shortly after the destruction of Ammonihah, Alma and Amulek went around preaching, “Holding forth things which must shortly come; yea, holding forth the coming of the Son of God, his sufferings and death, and also the resurrection of the dead.” They were preaching exactly the things that the people in Ammonihah rejected.

Then, in verse 20, the people began to ask questions, “And many of the people inquired concerning the place where the Son of God should come. And they were taught.” Alma must have received specific information by revelation that the Savior “would appear unto them after his resurrection.” This seems to be the first time that this important detail was spoken quite so clearly and publicly in the Book of Mormon. Earlier prophecies about the resurrection spoke about “all the earth [seeing] the salvation of the Lord” (1 Nephi 19:17), and about Christ appearing “to his people” in an old-world context in connection with the subsequent destruction of Jerusalem (2 Nephi 25:14). Learning this new expectation that the Lord would come to them in the new world, no doubt, filled the people of Alma “with great joy and gladness” (16:20).

Wherever Alma was preaching, among hostile opponents or with faithful followers, he was asked tough questions. No doubt he sometimes had to say things like, “I don’t know the answer to all these things.” Here he was asked about “the place where the Son of God should come.” But what were they asking? Did they want to know “Which holy place?” “Which temple?” “Which city or land?” “Which isle of the sea?” How specific was their question? Certainly, Alma knew that the Son of God would come. That much he knew. And he answered cautiously, “He will appear to them, but not until after his resurrection.” And that much was enough to satisfy them deeply.

Does this say something to us? We do not always know the answers to all the questions that are thrown at us. In that case, it is better to say we don’t know something than to speculate beyond the limits of our understanding, especially without first clarifying that what we are teaching is speculation rather than revealed knowledge. At the same time, it is also essential to say what we do know. Typically, we know more than we might think we know, and usually we know all that we need to know.

Book

50 Chapters

Items in the BMC Archive are made publicly available for non-commercial, private use. Inclusion within the BMC Archive does not imply endorsement. Items do not represent the official views of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or of Book of Mormon Central.