Evidence #367 | September 5, 2022

Book of Mormon Evidence: Periphrastic Did

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

Abstract

The Book of Mormon extensively uses a grammatical form called periphrastic did in a manner consistent with texts from the 1500s and 1600s but markedly different from standard 19th century usage. This syntactic feature supports the miraculous nature of the Book of Mormon’s translation.Throughout the Book of Mormon, the verb did (including do and does) is often used as an auxiliary verb, as in the phrase “his soul did rejoice” (1 Nephi 1:15).1 Grammatically speaking, this type of past-tense usage to affirm simple declarative statements is periphrastic.2 Periphrastic did usage can be divided into three main subcategories:3

1. Adjacency: Where did is immediately followed by the verb it is affirming.

Example: “his soul did rejoice” (1 Nephi 1:15)

2. Intervening Subject: Where a subject is inserted between did and the verb it is affirming.

Example: “on this wise did he speak unto me” (Jacob 7:6)

3. Intervening Adverbial: Where an adverb or an adverbial phrase is inserted between did and the verb.

Example: “I Nephi did again with my brethren go forth into the wilderness” (1 Nephi 7:3)

Overall, the Book of Mormon uses periphrastic did over 1700 times with over 400 different verbs, resulting in a total usage rate of 20.2%.4 This further breaks down into 92.2% adjacency (1,627 instances), 4.4% intervening subject (78 instances), and 3.4% intervening adverbial (59 instances).5

Periphrastic Did in Early Modern English

According to Stanford Carmack and Royal Skousen, “Beginning in the 1530s and continuing throughout the rest of that century, the periphrastic did flourished as a past-tense marker in positive statements.”6 For some texts in this time period, periphrastic did is used more than 50% of the time, while others have lower frequencies, ranging down to 5% or less.7 Often usage in this period “ebbs and flows” within a single text, as it does in the Book of Mormon.8 The following chart compares an unusually high concentration in a passage from 1 Nephi with a text written by William Marshall in 1543.9

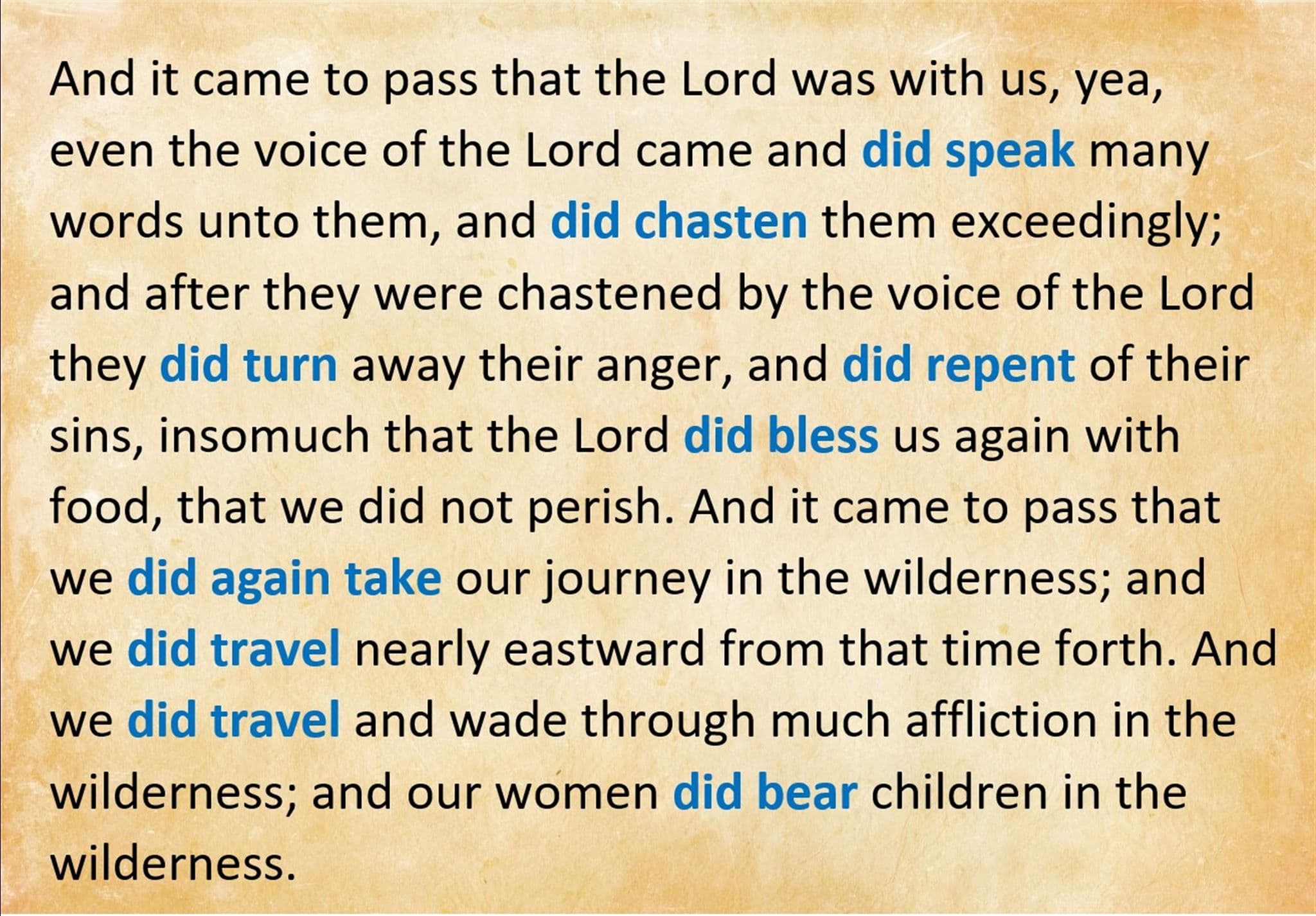

1 Nephi 16:39–17:1 | A Plain and Godly Exposition (1543) |

And it came to pass that the Lord was with us, yea, even the voice of the Lord came and did speak many words unto them, and did chasten them exceedingly; and after they were chastened by the voice of the Lord they did turn away their anger, and did repent of their sins, insomuch that the Lord did bless us again with food, that we did not perish. And it came to pass that we did again take our journey in the wilderness; and we did travel nearly eastward from that time forth. And we did travel and wade through much affliction in the wilderness; and our women did bear children in the wilderness. | The disciples of John did fast, but they did backbite the disciples of Christ and spake evil of them, for that they did more seldom fast. The Manichees did abstain and forbear from all manner of beasts or sensible creatures: but they did dispraise and condemn the creature of god: and secretly and in corners did fill themselves with delicious meats both more dainty and also more costly. The pharisees did pray, but they did it in the heads of many ways, where they might be most seen. In their chambers, either they did occupy themselves about trifles, or else did count and tell money. |

Overall, “the Book of Mormon’s past-tense usage agrees with Early Modern English usage on multiple levels, particularly the patterns prevalent from the mid-1500s to the last part of the 1500s and then extending, but diminishing, throughout the 1600s until disappearing around 1700.”10 Areas of similarity include “rate of occurrence, syntactic distribution, and individual verb use.”11 The following chart compares the rate of occurrence and syntactic distribution for the Book of Mormon and 7 texts from the 1500s.12

Author/Text | Year | Periphrastic did | Adjacency | Intervening Subject | Intervening Adverbial |

Marshall | 1534 | 38% | 76.5% | 7.4% | 18.9% |

Elyot | 1537 | 22% | 94% | 2% | 4% |

Boorde | 1542 | 52% | 93% | 2% | 5% |

Harpsfield | 1557 | 8.5% | 33.5% | 18.5% | 48% |

Machyn | 1563 | 18% | 96.2% | 3.3% | 0.5% |

Studley | 1574 | 6.7% | 59.4% | 1.9% | 38.7% |

Daniel | 1576 | 51% | 86.9% | 6% | 8.1% |

Book of Mormon | 1829 | 20.2% | 92.2% | 4.4% | 3.4% |

Naturally, there is variation among all these texts, but several of them have percentages comparable to the Book of Mormon in one or more domain.13 Interestingly, the texts with higher overall levels of periphrastic did also tend to have high levels of adjacency, just like the Book of Mormon. The works written by Elyot and Machyn are particularly similar. The Book of Mormon also sometimes parallels Early Modern usage rates on a verb-by-verb basis. The following chart provides comparative rates for 13 verbs analyzed by Carmack, 10 of which have similar rates of periphrastic did usage.14

Verb | Early Modern English | Book of Mormon |

Become | Low | Low |

Begin | Low | Low |

Minister | High | High |

Prosper | High | High |

Say | Low | Low |

Take | Medium | Medium |

Cease | Medium-High | High |

Come | Low | Medium-Low |

Die | Low | Zero |

Preach | Medium-High | High |

Go | Low | Medium |

See | Medium | Low |

Behold | High | Low |

Periphrastic Did through the Centuries

Generally speaking, the overall rate of periphrastic did in the English language has always been comparatively low. Although some authors in the 1500–1600s used it at high frequencies (some over 50%), it appears to have never averaged above 10% in the general textual record.15 Its rates then fell precipitously in the late 1600s and early 1700s.

Using modern databases to help verify the results of prior research on this topic, Carmack concluded that periphrastic did “had all but vanished sometime in the 1700s.”16 By the 1820s, the usage rates, estimated to be at or below 1%, “were less than half of 1700 levels and about the same as present-day levels of use.”17 Thus, the Book of Mormon was published more than 200 years after the short-lived surge of periphrastic did in the 1500s.

The King James Bible

The Book of Mormon’s usage rates in this domain most likely weren’t derived through imitation of the King James Bible. As demonstrated in the following chart, the periphrastic did rates for each text are different in syntactic distribution and especially in overall frequency.18

Text | Year | Periphrastic did | Adjacency | Intervening Subject | Intervening Adverbial |

Bible | 1611 | 1.7% | 72.7% | 24% | 3.3% |

Book of Mormon | 1829 | 20.2% | 92.2% | 4.4% | 3.4% |

The Bible doesn’t come close to the Book of Mormon’s high 20.2% overall usage rate, and its adjacency rate is approximately 20% lower (with the use of intervening subject being about 20% higher). There are also differences when it comes to individual verbs. Most notably, a significant portion of the Bible’s adjacent use of periphrastic did comes from a single verbal phrase—did eat (or didst eat)—which is used 115 times.19 In contrast, the Book of Mormon uses this phrase only once. Here are further examples of notable verbal dissimilarities:20

Differences | King James Bible | Book of Mormon |

Instances of did eat | 115 | 1 |

Instances of did eat & drink | 20 | 0 |

Instances of did go | 0 | 57 |

Instances of did cause | 2 | 50 |

Instances of did come | 1 | 41 |

Instances of did cry | 1 | 31 |

Instances of did have | 0 | 19 |

Instances of multiple ellipsis | 0 | 6 |

Rate of did preach | 0% | 78% |

Rate of did minister | 6% | 74% |

Rate of did pursue | 3% | 59% |

Rate of did pitch | 1% | 54% |

Rate of did build | 4% | 56% |

Pseudo-biblical Texts

As another control, Carmack and Skousen compared the Book of Mormon’s periphrastic did usage with several pseudo-biblical texts from the late 1700s and early 1800s:21

Text / Author | Year | Periphrastic did | Adjacency | Intervening Subject | Intervening Adverbial |

John Leacock | 1774 | less than 2% | 57% | 43% | 0% |

Richard Snowden | 1796 | 1% | 8% | 92% | 0% |

Michael Linning | 1809 | less than 1% | 0% | 100% | 0% |

Gilbert Hunt | 1816 | 2% | 5% | 95% | 0% |

Ethan Smith | 1823 | 0.6% | 12.5% | 37.5% | 75% |

Book of Mormon | 1829 | 20.2% | 92.2% | 4.4% | 3.4% |

The key indicator, of course, is that all of the pseudo-biblical texts have overall usage rates similar to that of the Bible (each with 2% or less) but far less than the Book of Mormon’s 20.2%. Nor do any of them approach the Book of Mormon’s 92.2% adjacency rate. Leacock’s text comes the closest on that front, but its already limited data is somewhat misleading due to its use of verbs that maintained higher-than-normal rates for periphrastic did.22

The following chart may help put the Book of Mormon’s high adjacency rate into perspective.23 It’s 1,627 instances are staggering when contrasted with the pseudo-biblical texts, none of which have more than 4 clearly viable instances.24

Text / Author | Year | Approximate Total Word Count | Total Adjacency Usage |

John Leacock | 1774 | 17,000 | 4 |

Richard Snowden | 1796 | 56,000 | 1 |

Michael Linning | 1809 | 22,000 | 0 |

Gilbert Hunt | 1816 | 49,000 | 1 |

Ethan Smith | 1823 | 57,000 | 1 |

Book of Mormon | 1829 | 270,000 | 1,627 |

Other 19th Century Texts

The stark results reported above are somewhat tempered by the fact that a small number of texts from the 19th century are known to have high periphrastic did/do rates.25 Most notable is the Chronicles of Eri, written by Roger O’Connor and published in 1822. Its periphrastic did rate most likely exceeds that of the Book of Mormon. It is possible, however, that its unusual usage is partly due to the author’s extensive literary knowledge and Irish background (as well as the text’s Irish content).26

Also of note is that when compared to O’Connor’s work, the Book of Mormon has noticeably lower relative rates for some verbs (did begin, did say, did see, and did speak), which better reflects Early Modern tendencies. The Book of Mormon also has a few subtypes not found in the Chronicles of Eri that were rare in Early Modern English and highly unlikely to all show up together in a single 19th century text. Thus, while Chronicles of Eri, along with a few other 19th century texts with higher rates, demonstrate that robust periphrastic did usage wasn’t an impossibility for 19th century authors, the specific usage patterns in the Book of Mormon are still uniquely archaic.27

The Absence of Periphrastic Did in Joseph Smith’s Writings

Joseph Smith’s 1832 account of his personal history, much of which was written in his own hand, is a valuable resource for assessing his personal language patterns near the time of the Book of Mormon’s translation.28 In his analysis of this account, Carmack found that there “is no did-periphrasis in positive declarative statements in the 1832 History, even though 88 past-tense main verbs are present. To match Book of Mormon rates there would need to be 26 instances of periphrastic did in this account.”29

Ten early letters written by Joseph Smith have also been searched. They have no fewer than 44 regular past tense verbs and yet only one instance of periphrastic did. When these letters are added to Joseph Smith’s 1832 history, his early writings manifest approximately 0.6% periphrastic did usage. Although it comes from a limited sample, this usage rate is comparable to the pseudo-biblical texts and doesn’t come close to the Book of Mormon’s 20.2% rate.30

Conclusion

For a text produced in 1829, the Book of Mormon’s high concentration and unique patterns of periphrastic did usage is highly unusual. With over 1700 instances spread out among more than 400 verbs, the legitimacy of this textual feature can’t be questioned.31 The text’s strong preference for adjacency is also noteworthy.

Could Joseph Smith have been responsible for the Book of Mormon’s periphrastic did usage? Perhaps he was one of those rare authors who picked up on this tendency through exposure to Early Modern English texts (despite their being largely inaccessible to someone in his circumstances).32 Or perhaps he noticed periphrastic did usage in the Bible and then considerably expanded its frequency, adjusted its syntactic distribution, and drastically changed its verbal tendencies.

While not inconceivable, such scenarios seem doubtful.33 The minimal use of periphrastic did in Joseph’s personal writings, its minimal and verbally different usage in the Bible, its minimal and syntactically different usage in a sampling of contemporary pseudo-biblical texts, and its very limited use in the broader corpus of 19th century texts all point in the other direction. Moreover, those few 19th century texts with rates comparable to the Book of Mormon, like the Chronicles of Eri, lack the Book of Mormon’s rare archaic subtypes and verbal patterns. If Joseph were responsible for the English wording of the Book of Mormon’s translation, it is more likely that its contents would reflect the standard usage of his day, or the slightly heightened but still minimal usage predominant in the pseudo-biblical literature.

The Book of Mormon’s unusually high use of periphrastic did with high adjacency is consistent with a number of other studies which argue that the text’s language largely derives from Early Modern English, rather than from Joseph Smith’s 19th century dialect.34 When viewed collectively, this data supports the position that the Book of Mormon’s English translation was revealed to Joseph Smith word for word by the gift and power of God.

Royal Skousen with the collaboration of Stanford Carmack, The Nature of the Original Language, Parts 3–4 of The History of the Text of the Book of Mormon, Volume 3 of The Critical Text of the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: FARMS and BYU Studies, 2018) 564–574.

Stanford Carmack, “How Joseph Smith’s Grammar Differed from Book of Mormon Grammar: Evidence from the 1832 History,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 25 (2017): 239–259.

Stanford Carmack, “The Implications of Past-Tense Syntax in the Book of Mormon,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 14 (2015): 119–186.

- 1. See Royal Skousen with the collaboration of Stanford Carmack, The Nature of the Original Language, Parts 3–4 of The History of the Text of the Book of Mormon, Volume 3 of The Critical Text of the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: FARMS and BYU Studies, 2018) 564–574; Stanford Carmack, “The Implications of Past-Tense Syntax in the Book of Mormon,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 14 (2015): 119–186.

- 2. The verbs did, do, and does are all still regularly used today as auxiliary verbs in various contexts: to show emphasis (“He did throw the ball!”), to negate a verb (“He did not throw the ball”), to show contrast (“Unlike the other players, he did throw the ball”), to give a command (“Do throw the ball, now!”), and to ask a question (“Did he throw the ball?”). Only the use of these verbs (do, did, does) to affirm simple declarative statements (“He did throw the ball”) has become obsolete. See Carmack, “The Implications of Past-Tense Syntax in the Book of Mormon,” 121.

- 3. See Skousen and Carmack, The Nature of the Original Language, 567. Note that the terminology used here differs somewhat from that presented in Carmack, “The Implications of Past-Tense Syntax in the Book of Mormon,” 122, which describes “intervening subject” as “inversion.” Also this evidence summary will not discuss a fourth subcategory which Carmack describes as “ellipsis.”

- 4. See Skousen and Carmack, The Nature of the Original Language, 566. The authors further explain, “In order to determine this rate, we considered 524 different verbs that take the simple past-tense form in the earliest text of the Book of Mormon. Most of these have instances of positive declarative periphrastic did, but 109 do not. In estimating the percentage of positive declarative periphrastic did in the Book of Mormon, we decided to include in the estimate the highly frequent, but mostly invariant phrase ‘came to pass’ as well as to limit counts to where did immediately precedes the infinitive form of the verb come (that is, ‘did come to pass’). This inclusion makes for a rather strong bias against periphrastic did since there are 1,404 instances of “came to pass” in the original text but only two of ‘did come to pass,’ in Helaman 11:20 and 3 Nephi 1:26” (p. 566). In other words, the unusually high usage of a single phrase (“it came to pass”) brings down the overall periphrastic did rate considerably. Carmack’s previous estimate for overall periphrastic did usage in the Book of Mormon was 27%, partly because “it came to pass” was excluded from the analysis. See Carmack, “The Implications of Past-Tense Syntax in the Book of Mormon,” 137, 154.

- 5. See Skousen and Carmack, The Nature of the Original Language, 567.

- 6. Skousen and Carmack, The Nature of the Original Language, 567. It should be noted that the heading for this chapter is different in that it attributes its contents first to Stanford Carmack and second to Royal Skousen, suggesting that Carmack took the lead in its authorship. For this reason, whenever this reference is cited, Carmack will be listed as the first author throughout the body of this article, with Skousen following.

- 7. See Skousen and Carmack, The Nature of the Original Language, 568; Carmack, “The Implications of Past-Tense Syntax in the Book of Mormon,” 169.

- 8. Skousen and Carmack, The Nature of the Original Language, 570.

- 9. See Skousen and Carmack, The Nature of the Original Language, 566–577.

- 10. Skousen and Carmack, The Nature of the Original Language, 566.

- 11. Skousen and Carmack, The Nature of the Original Language, 567. Syntactic distribution refers to the varying rates of adjacency, intervening subject, and intervening adverbial.

- 12. Chart data derived from Carmack, “The Implications of Past-Tense Syntax in the Book of Mormon,” 169; See also, Skousen and Carmack, The Nature of the Original Language, 570: “In the sixteenth century we can find heavy periphrastic did syntax in a number of lesser-known prose texts, although there is a least one famous work, a long extended poem, that has it: Edmund Spencer’s allegorical The Faerie Queene. … We have estimated the periphrastic did rate of The Faerie Queene at approximately 18 percent.”

- 13. It should be clarified that the position of Carmack and Skousen isn’t that the Book of Mormon follows the overall periphrastic did rates in the 1500s and 1600s. Rather, their position is that when it comes to this syntactic feature most of the known texts with rates comparable to the Book of Mormon come from that time general period. The Book of Mormon fits right in with multiple 16th century texts, whereas it looks very different from most 19th century texts.

- 14. Carmack, “The Implications of Past-Tense Syntax in the Book of Mormon,” 159.

- 15. Carmack, “The Implications of Past-Tense Syntax in the Book of Mormon,” 143–147.

- 16. Carmack, “The Implications of Past-Tense Syntax in the Book of Mormon,” 143. Carmack first looked at the conclusions of the Swedish linguist Alvar Ellegård. He then used different types of searches in modern data bases to confirm that Ellegård’s conclusions were essentially correct. This included searching modern databases and a sampling of pseudo-biblical texts for features like adjacency, ellipsis, and specific verbs. See Carmack, “The Implications of Past-Tense Syntax in the Book of Mormon,” 123–149.

- 17. Carmack, “The Implications of Past-Tense Syntax in the Book of Mormon,” 145–146.

- 18. The data for these rates derives from Skousen and Carmack, The Nature of the Original Language, 570. The percentages for biblical usage reported here are slightly different from the rates presented in Carmack, “The Implications of Past-Tense Syntax in the Book of Mormon,” 173, which reports an adjacency rate of 61% and an intervening subject rate of 31%. The overall periphrastic did usage, however, is the same for both estimates (1.7%).

- 19. See Skousen and Carmack, The Nature of the Original Language, 570; Carmack, “The Implications of Past-Tense Syntax in the Book of Mormon,” 177–179.

- 20. See Carmack, “The Implications of Past-Tense Syntax in the Book of Mormon,” 173. Interestingly, the Book of Mormon has a much closer match with the Early Modern writings of Henry Machyn, based on analysis of verbs with at least 10 usages or more in each text. “The correlation of [periphrastic] did rates for 75 individual verbs in the KJB and in the BofM is weak—30% (p < 1%). Performing a similar correlation between Machyn’s Diary (from the 1550s and ’60s) and the BofM yields a relatively strong correlation of 79% (12 verbs; p < ½%).” Accordingly, “We are 99% confident that only a weak relationship exists between the BofM and KJB, and we are 99.5% confident that a fairly strong relationship exists between the BofM and Machyn’s writing.” Carmack, “The Implications of Past-Tense Syntax in the Book of Mormon,” 172.

- 21. Data has been gathered from the following publications: Skousen and Carmack, The Nature of the Original Language, 570–574; Carmack, “The Implications of Past-Tense Syntax in the Book of Mormon,” 163–168. For some counts there were minor discrepancies, likely due to slight adjustments in the criteria used in each study. In such cases, the data from the more recent publication (The Nature of the Original Language) has been prioritized.

- 22. See Skousen and Carmack, The Nature of the Original Language, 571, 574.

- 23. Total counts of adjacency in the pseudo-biblical texts were derived from Skousen and Carmack, The Nature of the Original Language, 570–573; Carmack, “The Implications of Past-Tense Syntax in the Book of Mormon,” 165. As for the approximate total word counts, most of them were calculated by WordCruncher. The only exception is Ethan Smith’s View of the Hebrews. Its total was derived by copying its text from archive.org and placing it in Microsoft Word (which automatically provides a word count). All counts were rounded to the nearest thousand.

- 24. Stated differently, the Book of Mormon has about 173 instances of adjacency for every instance in the pseudo-biblical texts (after their rates have been combined and normalized so that they can be meaningfully compared with the Book of Mormon). The pseudo-biblical texts average 9.4 instances for every 270,000 words, in contrast to the Book of Mormon’s 1,627 instances for the same amount. That ratio reduces down to 173 instances in the Book of Mormon for every instance in the pseudo-biblical texts.

- 25. The information in this section is based on unpublished research by Stanford Carmack and has been summarized here with his permission.

- 26. Irish is a Celtic language that prefixes a d sound to verb stems when they begin with a vowel sound, somewhat analogous to periphrastic did (which provides two d sounds before the verb).

- 27. A religious document produced by a Shaker community known as A Holy, Sacred and Divine Roll also has robust periphrastic did usage—almost 7%. A few other works with potentially high rates include Chronicles of Andrew (1815), Ye Ancient Chronicles of the Land of Gotham (1888), and an 1856 translation of Homer’s Iliad by Francis Norman. Carmack has noted that Norman’s translation may have used periphrastic did/do to help with rhyme and meter, as Edmund Spencer’s Faerie Queen (1590) most likely did. The other two texts are much shorter and therefore not as statistically significant. Carmack hasn’t analyzed these texts to get precise estimates of periphrastic did/do usage, but limited sampling suggests they each have higher-than-normal 19th century rates.

- 28. See “History, circa Summer 1832,” p. 1, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed August 22, 2022.

- 29. Stanford Carmack, “How Joseph Smith’s Grammar Differed from Book of Mormon Grammar: Evidence from the 1832 History,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 25 (2017): 250.

- 30. This data comes from unpublished research by Stanford Carmack and has been summarized here with his permission.

- 31. It clearly isn’t an artifact of limited sampling or the result of an outsized usage of a single verb (such as the Bible’s strong preference for did/didst eat). It is a real textual phenomenon based on a robust and diverse set of verbal data.

- 32. Carmack notes that “access to the relevant texts was extremely limited in the 1820s, especially to someone living away from populated eastern cities with research libraries. And the 16c printed books containing the heavy use of this syntax were still largely to be found only in British libraries.” Carmack, “The Implications of Past-Tense Syntax in the Book of Mormon,” 185.

- 33. For an in-depth discussion of why biblical imitation is doubtful source of the Book of Mormon’s periphrastic did usage, see Carmack, “The Implications of Past-Tense Syntax in the Book of Mormon,” 172–179.

- 34. For a fairly comprehensive survey of these studies, see Royal Skousen with the collaboration of Stanford Carmack, The Nature of the Original Language, Parts 3–4 of The History of the Text of the Book of Mormon, Volume 3 of The Critical Text of the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: FARMS and BYU Studies, 2018); Royal Skousen, “The Language of the Original Text of the Book of Mormon,” BYU Studies Quarterly 57, no. 3 (2018): 81–110; Stanford Carmack, “A Comparison of the Book of Mormon’s Subordinate That Usage,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 50 (2022): 1–32; Stanford Carmack, “The Book of Mormon’s Complex Finite Cause Syntax,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 49 (2021): 113–136; Stanford Carmack, “Personal Relative Pronoun Usage in the Book of Mormon: An Important Authorship Diagnostic,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 49 (2021): 5–36; Stanford Carmack, “Pitfalls of the Ngram Viewer,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 36 (2020): 187–210; Stanford Carmack, “Bad Grammar in the Book of Mormon Found in Early English Bibles,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 36 (2020): 1–28; Stanford Carmack, “Is the Book of Mormon a Pseudo-Archaic Text?” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 28 (2018): 177–232; Stanford Carmack, “On Doctrine and Covenants Language and the 1833 Plot of Zion,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 26 (2017): 297–380; Stanford Carmack, “How Joseph Smith’s Grammar Differed from Book of Mormon Grammar: Evidence from the 1832 History,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 25 (2017): 239–259; Stanford Carmack, “Barlow on Book of Mormon Language: An Examination of Some Strained Grammar” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 27 (2017): 185–196; Stanford Carmack, “The Case of Plural Was in the Earliest Text,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 18 (2016): 109–137; Stanford Carmack, “The Case of the {-th} Plural in the Earliest Text,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 18 (2016): 79–108; Stanford Carmack, “Joseph Smith Read the Words,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 18 (2016): 41–61; Stanford Carmack, “The More Part of the Book of Mormon is Early Modern English,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 18 (2016): 33–40; Stanford Carmack, “What Command Syntax Tells Us About Book of Mormon Authorship,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 13 (2015): 175–217; Carmack, “The Implications of Past-Tense Syntax in the Book of Mormon,” 119–186; Stanford Carmack, “Why the Oxford English Dictionary (and not Webster’s 1828),” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 15 (2015): 65–77; Stanford Carmack, “A Look at Some ‘Nonstandard’ Book of Mormon Grammar,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 11 (2014): 209–262. In addition to these articles, here are a few presentations (recorded on video) by these same authors: Royal Skousen and Stanford Carmack, “Editing Out the ‘Bad Grammar’ in the Book of Mormon,” The Interpreter Foundation, 2016; Stanford Carmack, “Exploding the Myth of Unruly Book of Mormon Grammar: A Look at the Excellent Match with Early Modern English,” The Interpreter Foundation/BYU Studies, 2015; Royal Skousen, “‘A theory! A theory! We have already got a theory, and there cannot be any more theories!’” The Interpreter Foundation/BYU Studies, 2015.