Evidence #360 | July 27, 2022

Book of Mormon Evidence: Exodus and Alma’s People

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

Abstract

The account of the deliverance of Alma and his people contains numerous parallels with the Israelite Exodus from Egypt.In a study of the role of the Exodus in biblical memory, Ronald Hendel observes, “the deliverance from Egypt is the main historical warrant for the religious bond between Yahweh and Israel; it is the gracious act of the great lord for his people on which rests the superstructure of Israelite belief and practice.”1

As with the Bible, the memory of the Israelite Exodus from Egypt also significantly shaped narratives in the Book of Mormon, a record of a remnant of the house of Israel.2 Deliverance events among the people of Nephi are told in ways that recall the biblical Exodus and thereby lend authority to the prophetic leaders who, like Moses, helped their people escape from various types of bondage. Alma, a repentant former priest of the wicked King Noah, is one example of such a leader.

A New King

After settling in the land of Helam, Alma and his people prospered until the Lamanites discovered their whereabouts. The king of the Lamanites then appointed Amulon, who had once been one of King Noah’s wicked priests, to be “a king and a ruler” over Alma’s people (Mosiah 23:39). Additionally, we are told that Amulon “knew Alma that he had been one of the king’s priests” (Mosiah 23:9).

This appears to be an inversion of the Exodus account, which begins, “Now there arose up a new king over Egypt, which knew not Joseph” (Exodus 1:8). In each case, a new king comes into power and the narrative emphasizes that this king “knew” or “knew not” the spiritual leader of God’s chosen people.

Cunning Taskmasters

In response to the growing Israelite population, the new king of Egypt declared, “Come on, let us deal wisely with them; lest they multiply, and it come to pass, that, when there falleth out any war, they join also unto our enemies, and fight against us, and so get them up out of the land” (Exodus 1:10). The context here suggests that “wisely” (Hebrew: ḥāḵam) refers to worldly wisdom or cunning, which is why other biblical translations often render this term as “shrewdly.”3 The Lamanites in Alma’s exodus story possessed the same quality: “the Lamanites … began to be a cunning and a wise people, as to the wisdom of the world, yea, a very cunning people, delighting in all manner of wickedness and plunder” (Mosiah 24:7).

In both stories, the cunning of the oppressor nation is immediately connected to their enslavement of God’s people. After the comment about Pharaoh dealing “wisely” with the Israelites, the next verse in the biblical story states that the Egyptians “set over them taskmasters to afflict them with their burdens” (v. 11). The same sequence shows up in Alma’s exodus account. Right after commenting on the “cunning” and “wisdom” of the Lamanites, the narrator reports that Amulon “put tasks upon” Alma’s people “and put task-masters over them” which led to “great … afflictions” (Mosiah 24:9).

They “Knew Not God”

In the account in the book of Mosiah, the narrator emphasizes that the Lamanites who had captured Alma and his people “knew not God” (Mosiah 24:5). This phrasing doesn’t seem to be included by happenstance, considering that a main theme in the Exodus account is Pharaoh’s lack of familiarity and belief in the God of Israel. In his first meeting with Moses and Aaron, Pharaoh declared, “Who is the Lord, that I should obey his voice to let Israel go? I know not the Lord, neither will I let Israel go” (Exodus 5:2). The theme of knowing (or not knowing) God, including a knowledge of his attributes and greatness, is brought up over and over throughout the biblical exodus narrative (see Exodus 6:7; 7:5, 17; 8:10, 22; 9:14, 29; 10:2; 14:4, 18; 16:6, 12).

False Promises

On various occasions throughout the biblical account, Pharaoh falsely promised to set the children of Israel free. For instance, after suffering a pestilence of frogs, Pharaoh asked Moses, “Entreat the Lord, that he may take away the frogs from me, and from my people; and I will let the people go, that they may do sacrifice unto the Lord” (Exodus 8:8). Yet after the plague was removed, “Pharaoh saw that there was respite,” and “he hardened his heart” and refused to let them go (v. 15). This scenario was repeated several times over (Exodus 8:28; 32; 9:28, 35; 10:17, 20; 12:31–32; 14:5).

The Lamanites in Alma’s exodus account also gave a false promise of freedom:

And it came to pass that the Lamanites promised unto Alma and his brethren, that if they would show them the way which led to the land of Nephi that they would grant unto them their lives and their liberty. But after Alma had shown them the way that led to the land of Nephi the Lamanites would not keep their promise; but they set guards round about the land of Helam, over Alma and his brethren. (Mosiah 23:36–37)

Cries, Punishment, and the Threat of Death

When they were in Egypt, the children of Israel “sighed by reason of the bondage, and they cried, and their cry came up unto God by reason of the bondage” (Exodus 2:23). When Pharaoh heard of the Israelites desire to leave Egypt, he declared, “therefore they cry, saying, Let us go and sacrifice to our God. Let there more work be laid upon the men, that they may labour therein” (Exodus 5:8–9). Not only were their burdens increased, but the Israelites felt that they were in danger of death, complaining that Moses had metaphorically “put a sword in [the Egyptians’] hand to slay us” (v. 21).

Alma and his people were also greatly afflicted by their oppressors, and “so great were their afflictions that they began to cry mightily to God” (Mosiah 24:10; v. 12). When he saw this, Amulon “put guards over them to watch them, that whosoever should be found calling upon God should be put to death” (Mosiah 24:11). Thus, in both narratives, after the enslaved people cried unto the Lord, their captors further oppressed them and their lives became endangered.

Remembering the Covenant

When the children of Israel were afflicted in Egypt, “God heard their groaning, and God remembered his covenant with Abraham, with Isaac, and with Jacob” (Exodus 2:24). When these afflictions intensified, the Lord told Moses, “I have also heard the groaning of the children of Israel, whom the Egyptians keep in bondage; and I have remembered my covenant. Wherefore say unto the children of Israel, I am the Lord, and I will … rid you out of their bondage” (Exodus 6:5).

The Lord also heard the cries of Alma and his people, after which he said unto them, “Lift up your heads and be of good comfort, for I know of the covenant which ye have made unto me: and I will covenant with my people and deliver them out of bondage” (Mosiah 24:13). In each story, therefore, the Lord connects his promise to deliver his people “out of … bondage” with his remembrance of a prior “covenant.”

Deliverance from Burdens

In both exodus narratives, the Lord also promised to relieve “burdens” in connection to “bondage.” Through Moses, he said, “I will bring you out from under the burdens of the Egyptians, and I will rid you out of their bondage, and I will redeem you with a stretched out arm” (Exodus 6:6). Through his prophet Alma, the Lord promised, “I will ease the burdens which are put upon your shoulders, that even you cannot feel them upon your backs, even while ye are in bondage” (Mosiah 24:14).

On the Morrow

On several occasions in the biblical Exodus, Moses declared that a sign or a wonder would be delivered “to morrow” or “on the morrow” (Exodus 8:10, 23; 9:5–6, 18, 10:4). Although the word “morrow” is never stated in the Passover narrative, the nature of the miracle clearly implies the same sort of immediacy, with the miracle taking place at night and the people being delivered the next day (Exodus 10–13).4

This imagery resurfaces again in the account of Joshua right before the Israelites passed over the Jordan river: “And Joshua said unto the people, Sanctify yourselves: for to morrow the Lord will do wonders among you” (Joshua 3:5). This river crossing, as well as many other details in the Joshua narrative, clearly adhere to the Exodus pattern.5 With this backdrop in mind, the Lord’s statements to Alma in Mosiah 24:16 takes on additional significance: “Be of good comfort, for on the morrow I will deliver you out of bondage.”

The Lord Visits His People in Their Afflictions

The Lord commanded Moses to tell the children of Israel, “I have surely visited you and seen that which is done to you in Egypt: And I have said, I will bring you up out of the affliction of Egypt” (Exodus 3:16–17). He also promised them, “And I will take you to me for a people, and I will be to you a God: and ye shall know that I am the Lord your God, which bringeth you out from under the burdens of the Egyptians” (Exodus 6:7).

When comforting and strengthening Alma and his people, the Lord similarly explained, “And this will I do that ye may stand as witnesses for me hereafter, and that ye may know of a surety that I, the Lord God, do visit my people in their afflictions” (Mosiah 24:14).

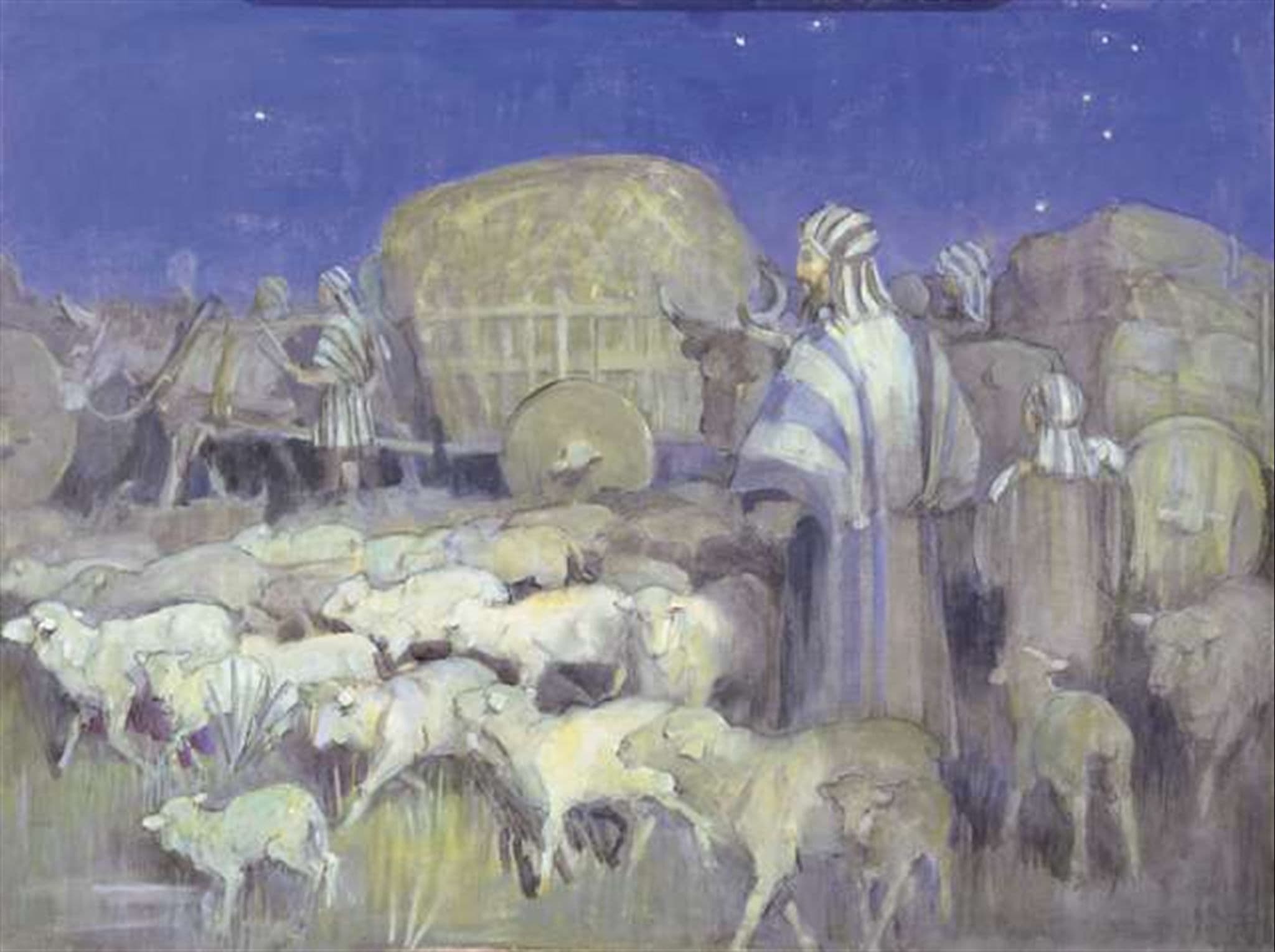

Hasty Night-Time Preparations and Departure

In the biblical account, Pharaoh “called for Moses and Aaron by night, and said, Rise up, and get you forth from among my people, both ye and the children of Israel; … Also take your flocks and your herds, as ye have said, and be gone” (Exodus 12:31–32). The people also “took their dough [a grain product] before it was leavened” (v. 34). The Egyptians “were “urgent upon the people, that they might send them out of the land in haste” (v. 33). The Lord further declared that this was “a night to be much observed unto the Lord for bringing them out from the land of Egypt: this is that night of the Lord to be observed of all the children of Israel in their generations” (v. 42).

This may help to explain the emphasis on the hasty night-time preparations and departure in the account in Mosiah, including the mention of their gathering flocks and grain: “Now it came to pass that Alma and his people in the night-time gathered their flocks together, and also of their grain; yea, even all the night-time were they gathering their flocks together” (Mosiah 24:18). The Lord then told Alma, “Haste thee and get thou and this people out of this land” (v. 23).

The People Camp

When they went out of bondage the children of Israel camped near the Red Sea (Exodus 14:2). When Alma and his people escaped from bondage in the land of Helam they camped in valley which they named after Alma (Mosiah 24:20).

Futile Pursuit

After the children of Israel camped near the Red Sea, the Lord warned them that Pharaoh “shall follow after them,” yet the Lord also promised to thwart their enemies: “I will be honoured upon Pharaoh, and upon all his host; that the Egyptians may know that I am the Lord” (Exodus 14:4). Just as the Lord predicted, “the Egyptians pursued after them” (v. 9), yet the “Lord overthrew the Egyptians in the midst of the sea. And the waters returned, and covered the chariots, and the horsemen, and all the host of Pharaoh” (v. 27–28).

After Alma and his people camped in the valley, the Lord similarly warned them that “the Lamanites have awakened and do pursue thee; therefore, get thee out of this land, and I will stop the Lamanites in this valley that they come no further in pursuit of this people” (Mosiah 24:23). The Lord apparently did so, seeing that Alma and his people arrived safely in the land of Zarahemla (v. 25). Thus, in each story the Lord warned of a pursuit, promised to thwart the enemy, and then exercised his divine powers of protection.

Praise and an Etiology

After escaping through the Red Sea, the children of Israel collectively sang a song of praise and thanksgiving unto the Lord (Exodus 15:1, 20–21), declaring things like “Thou in thy mercy hast led forth the people which thou has redeemed [i.e. freed from bondage]” (v. 13) and “Who is like unto thee, O Lord, among the gods? who is like thee, glorious in holiness, fearful in praises, doing wonders?” (v. 11; cf. Exodus 9:14).

After initially escaping from the Lamanites, Alma and his people similarly

poured out their thanks to God because he had been merciful unto them, and eased their burdens, and had delivered them out of bondage; for they were in bondage, and none could deliver them except it were the Lord their God. And they gave thanks to God, yea, all their men and all their women and all their children that could speak lifted their voices in the praises of their God. (Mosiah 24:21–22).6

Interestingly, each of these outpourings of praise is closely connected to a wilderness journey and a named location for which an etiology (explanation of origin) is given. In the biblical narrative, the people traveled into the wilderness until they came to Marah, and they “could not drink of the waters of Marah, for they were bitter: therefore the name of it was called Marah” (Exodus: 15:23). This is reported immediately after the mention of the song of praise.

Likewise, right before Alma’s people praised the Lord, the narrator notes that “Alma and his people departed into the wilderness; and when they had traveled all day they pitched their tents in a valley, and they called the valley Alma, because he led their way in the wilderness” (Mosiah 24:20).

A Prophet Like Moses

Alma, in his capacity as a righteous prophet, is clearly portrayed as a Moses-like figure who was an instrument in the hands of God in delivering his repentant people. When they wanted to make him a king in the land of Helam, Alma adamantly refused, reminding them of how they had escaped from Egyptian-like bondage to King Noah and his priests:

And now I say unto you, ye have been oppressed by king Noah, and have been in bondage to him and his priests, and have been brought into iniquity by them; therefore, ye were bound with the bands of iniquity. And now as ye have been delivered by the power of God out of these bonds; yea, even out of the hands of king Noah and his people, and also from the bonds of iniquity, even so I desire that ye should stand fast in this liberty wherewith ye have been made free, and that ye trust no man to be a king over you (Mosiah 23:12–13).

Alma is likewise shown to be a prophet like Moses when he and his people were delivered from Lamanite bondage in Helam. The Lord told Moses, “certainly I will be with thee” (Exodus 3:11–12). To Alma he said, “Thou shalt go before this people, and I will go with thee and deliver this people out of bondage” (Mosiah 24:17). By casting Alma in the role of a prophet-deliverer like Moses, the narrator highlights the divine validity of Alma’s teachings against unrighteous kings and teachers, as well as his teachings concerning Christ.

In a study of the Moses type in the Bible, Dale Allison notes that prophets like Moses “tend to appear at crucial transitions” in the history of God’s people.7 Significantly, Alma also plays a central role in the Nephite transition from kingship to the reign of judges, as well as in the introduction of the Church of Christ to the people of Zarahemla, of which Alma the high priest was considered the prophetic founder (Mosiah 23:16; 29:47). The miraculous Exodus-like experiences of Alma and his people must have provided a sense of divine providence and guidance throughout these dramatic innovations and transitions.

Conclusion

When viewed collectively, the parallels between the deliverance of Alma and his people from bondage and the Israelite exodus from Egypt are striking and persuasive. They suggested that whoever authored the account in Mosiah 23–24 was not only intimately familiar with the Israelite Exodus, but was also aware of the manner in which later biblical texts consistently allude to Exodus themes and motifs. These parallels are understandable and even expected if the Book of Mormon is what it claims to be: a record from an ancient branch of Israel that perpetuated the literary and cultural traditions of their Hebrew ancestors.

S. Kent Brown, “The Exodus Pattern in the Book of Mormon,” BYU Studies 30, no. 3 (Summer 1990): 111–126, reprinted in S. Kent Brown, From Jerusalem to Zarahemla: Literary and Historical Studies of the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1998), 75–98.

David R. Seely, “‘A Prophet Like Moses’: Deuteronomy 18:15–18 in the Book of Mormon, the Bible, and the Dead Sea Scrolls,” in “To Seek the Law of the Lord”: Essays in Honor of John W. Welch (Orem, UT: Interpreter Foundation, 2017), 360–374.

Noel B. Reynolds, “The Israelite Background of Moses Typology in the Book of Mormon,” BYU Studies 44, no. 2 (2005): 5–23.

Noel B. Reynolds, “Lehi as Moses,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 9, no. 2 (2000): 26–35.

Terrrence L. Szink, “Nephi and the Exodus,” in Rediscovering the Book of Mormon: Insights You May Have Missed Before, ed., John L. Sorenson and Melvin J. Thorne (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1991), 50–51.

Alan Goff, “Mourning, Consolation, and Repentance at Nahom,” in Rediscovering the Book of Mormon: Insights You May Have Missed Before, ed., John L. Sorenson and Melvin J. Thorne (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1991), 92–99.

George S. Tate, “The Typology of the Exodus Pattern in the Book of Mormon,” in Literature of Belief: Sacred Scripture and Religious Experience, ed., Neal E. Lambert (Provo, UT: BYU Religious Studies Center, 1981), 245–262.

Bible

Book of Mormon

- 1. Ronald Hendel, “The Exodus in Biblical Memory,” Journal of Biblical Literature 120, no. 4 (2001): 601. See also R. Michael Fox, ed., Reverberations of the Exodus in Scripture (Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications/Wipf and Stock, 2014); David Daube, The Exodus Pattern in the Bible (London: Faber and Faber, 1963); Michael Fishbane, Biblical Interpretation in Ancient Israel (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988), 358–368; Yair Zakovitch, “And You Shall Tell Your Son”: The Concept of the Exodus in the Bible (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1991).

- 2. See for example, George S. Tate, “The Typology of the Exodus Pattern in the Book of Mormon,” in Literature of Belief: Sacred Scripture and Religious Experience, ed. Neal E. Lambert (Provo, UT: BYU Religious Studies Center, 1981), 245–262; S. Kent Brown, “The Exodus Pattern in the Book of Mormon,” BYU Studies 30, no. 3 (Summer 1990): 111–126, reprinted in S. Kent Brown, From Jerusalem to Zarahemla: Literary and Historical Studies of the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: BYU Religious Studies Center, 1998), 75–98; Terrrence L. Szink, “Nephi and the Exodus,” in Rediscovering the Book of Mormon: Insights You May Have Missed Before, ed. John L. Sorenson and Melvin J. Thorne (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1991), 50–51; Noel B. Reynolds, “The Israelite Background of Moses Typology in the Book of Mormon,” BYU Studies 44, no. 2 (2005): 14; David R. Seely, “‘A Prophet Like Moses’: Deuteronomy 18:15–18 in the Book of Mormon, the Bible, and the Dead Sea Scrolls,” in “To Seek the Law of the Lord”: Essays in Honor of John W. Welch (Orem, UT: Interpreter Foundation, 2017), 360–374.

- 3. See https://biblehub.com/exodus/1-10.htm.

- 4. The Lord told Moses, “Yet will I bring one plague more upon Pharaoh, and upon Egypt; afterwards he will let you go hence” (Exodus 11:1). This plague, which entailed the killing of all the firstborn of men and beasts in Egypt, was said to strike “about midnight” (vv. 4–5). Furthermore, the Israelites were to have their “loins girded, your shoes on your feet, and your staff in your hand; and ye shall eat it in haste,” suggesting that they would be departing in the morning (Exodus 12:11). After the plague struck, Pharaoh “called for Moses and Aaron by night, and said, Rise up, and get you forth from among my people, both ye and the children of Israel; and go, serve the Lord, as ye have said …. And the Egyptians were urgent upon the people, that they might send them out of the land in haste” (vv. 31–33). In addition, it is reported that the Israelites “baked unleavened cakes of the dough which they brought forth out of Egypt, for it was not leavened; because they were thrust out of Egypt, and could not tarry, neither had they prepared for themselves any victual” (v. 39). All of this indicates that the Lord indeed delivered the people on the morrow, immediately after the Passover, without delay.

- 5. See Dallaire and Morris, “Joshua and Israel’s Exodus from the Desert Wilderness,” 18–34.

- 6. For a related parallel in another Book of Mormon text, see Evidence Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Songs of Moses and Ammon,” Evidence# 0236, September 7, 2021, online at evidencecentral.org.

- 7. Dale C. Allison, The New Moses: A Matthean Typology (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 1993), 49.