Evidence #92 | September 19, 2020

Book of Mormon Evidence: System of Judges

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

Abstract

The Nephite system of judges has parallels with ancient forms of government, and yet substantially differs from the political system present in Joseph Smith’s early 19th century environment.The Nephite System of Judges

With none of his sons available to succeed him as king, Mosiah instituted governmental reforms, abolishing the kingship and establishing judges who were, in some form, elected by “the voice of the people” (Mosiah 29:25).1 In this process, the people “assembled themselves together in bodies throughout the land, to cast in their voices concerning who should be their judges” (Mosiah 29:39; cf. Alma 2:5–6).

While this may initially seem like a form of modern American democracy,2 careful analysis suggests otherwise. Chief judges among the Nephites were sometimes appointed by their predecessors, such as when Alma gave up the judgement-seat to Nephihah (see Alma 4:20). In other cases, the judgement-seat seems to have been mostly inherited from father to son, as when Pahoran was appointed to the judgement-seat after his father died (Alma 50:37–40), or when Pahoran’s sons contended for the throne after his passing (Helaman 1:2).

These and other features of Nephite government led legal scholar John W. Welch to describe the Nephites’ change from monarchy to judges as “more nominal and cosmetic than substantive.”3 American historian Richard Bushman has explained,

Although democratic elements were there—the judges were confirmed by the voice of the people—the “reign of the judges,” as the Book of Mormon calls the period, was a far cry from the republican government Joseph Smith knew. Life tenure and hereditary succession would have struck Americans as only slightly modified monarchy.4

Judges in Ancient Israel

Readers may wonder if the Nephite system of judges was modeled after the form of government found in early Israelite history, as recorded in the book of Judges. On its face, this is certainly possible, considering that the book of Judges (or a version of it) may very well have been preserved on the Brass Plates. Yet there are obstacles to envisioning the Nephite system as a complete restoration of the early Israelite pattern of governance.

For one thing, many readers have viewed the book of Judges as a series of disconnected narratives about “charismatic military leaders and war heroes” who “did little, if any, judging of legal disputes.”5 In addition, “The era of the shophetim [judges] we see in the book of Judges was one of a much more loosely organized tribal society without any strong central government, perhaps without any central government at all, whereas the Nephite system had a clear center and periphery manifested by the chief judge and lesser judges.”6

On the other hand, some similarities are noteworthy. Gregory Dundas has argued that both the prominent and lesser known figures in the book of Judges seem to have assumed a variety of governing roles, including acting as judges of the people.7 The chief judges in the Book of Mormon also seem to have led in various capacities, such as acting as prophets, participating in battles, and functioning as governors (see, for example, Alma 2:16). For this and other reasons, Dundas concluded, “It … seems reasonable to suppose that the era of the shophetim [judges] served as part of the background from which Mosiah and his contemporaries drew in their understanding of the ‘reign’ of judges.”8

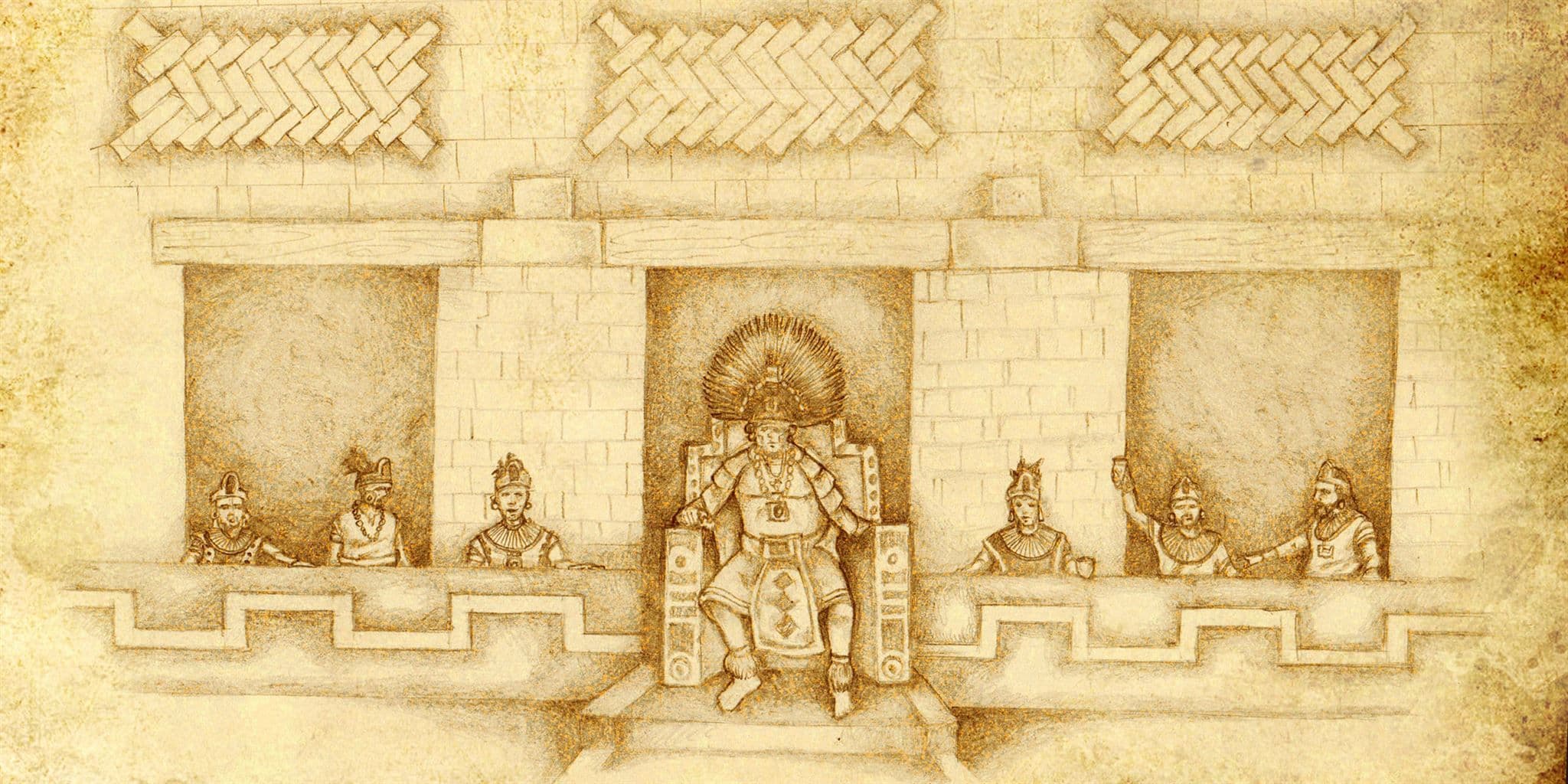

Systems of Judges in Mesoamerica

Parallels with ancient Mesoamerican governments may also be relevant. Brant A. Gardner has noted that “Mesoamerican monarchies existed on top of a system of rule that divided power among kin-based lineages, each with their own organizational structure.”9 Many cities had a popol nah (council house) “where non-ruling elite lineages might meet.” Archaeology “places this type of government in precisely the time period of Mosiah’s shift to the rule of judges.”10 As such, Gardner proposed,

What Mosiah did was remove the top layer of political authority by abolishing the position of king. This act easily moved rule to the next functioning level [the council of non-ruling elites, or “judges”] … It did not require the creation of any new level of government or even concept of government. It exalted an existing structure to the next higher level.11

Inscriptions indicate that in the ninth century AD, rather than being ruled by a king, Chichén Itzá was ruled “by council, by the heads of different lineages.”12 Gardner described their government as possibly being “the most parallel to what we see among the Nephites.”13 Even though this example post-dates the Book of Mormon, it is plausible that non-monarchal rule by a council of judges or governors from powerful lineages could have been established in earlier periods. As Gardner noted, “the structures that allowed it had been in place for a long time.”14

Conclusion

Commenting generally upon the Book of Mormon’s dissimilarity with American government and its similarities to the ancient world, Bushman concluded,

The Book of Mormon is not a conventional American book. Too much Americana is missing. … Historians will take a long step forward when they free themselves from the compulsion to connect all they find with Joseph Smith’s America and try instead to understand the ancient patterns deep in the grain of the book.

Gregory Steven Dundas, “Kingship, Democracy, and the Message of the Book of Mormon,” BYU Studies Quarterly 56, no. 2 (2017): 7–58.

Book of Mormon Central, “How Were Judges Elected in the Book of Mormon? (Mosiah 29:39),” KnoWhy 107 (May 25, 2016).

Brant A. Gardner, Traditions of the Fathers: The Book of Mormon as History (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2015), 242–253.

John W. Welch, The Legal Cases in the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: BYU Press and Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2008), 215–218.

Richard L. Bushman, “The Book of Mormon and the American Revolution,” BYU Studies 17, no. 1 (1976): 1–17, reprinted in Book of Mormon Authorship: New Light on Ancient Origins, ed. Noel B. Reynolds (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1982; reprinted by FARMS, 1996), 189–211.

- 1. See John W. Welch, The Legal Cases in the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: BYU Press and Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2008), 215–218.

- 2. Richard L. Bushman, “The Book of Mormon and the American Revolution,” Book of Mormon Authorship: New light on Ancient Origins, ed. Noel B. Reynolds (Provo UT: Religious Studies Center, 1982), 190–192.

- 3. Welch, Legal Cases, 215.

- 4. Bushman, “The Book of Mormon and the American Revolution,” 201.

- 5. Gregory Steven Dundas, “Kingship, Democracy, and the Message of the Book of Mormon,” BYU Studies Quarterly 56, no. 2 (2017): 37.

- 6. Dundas, “Kingship, Democracy, and the Message of the Book of Mormon,” 41.

- 7. Dundas, “Kingship, Democracy, and the Message of the Book of Mormon,” 39.

- 8. Dundas, “Kingship, Democracy, and the Message of the Book of Mormon,” 41; emphasis added.

- 9. Brant A. Gardner, Traditions of the Fathers: The Book of Mormon as History (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2015), 251.

- 10. Gardner, Traditions of the Fathers, 252. Subscript “2” next to Mosiah (indication that he is Mosiah the Second) silently omitted.

- 11. Gardner, Traditions of the Fathers, 252. Subscript “2” next to Mosiah (indication that he is Mosiah the Second) silently omitted.

- 12. David Drew, The Lost Chronicles of the Maya Kings (Berkley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 1999), 372. This parallel is pointed out in Gardner, Traditions of the Fathers, 251–252.

- 13. Gardner, Traditions of the Fathers, 252.

- 14. Gardner, Traditions of the Fathers, 252.