Evidence #145 | February 2, 2021

Book of Mormon Evidence: Destruction of Records

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

Abstract

The deliberate destruction of ancient records has a long history in ancient America and is consistent with the concern Nephite writers expressed over the dangers to their own literary tradition.Nephite Records

Book of Mormon prophets taught that their most valuable records were to be passed down from generation to generation with stern admonitions to keep them safe from abuse and destruction (Alma 37:14–18). Nephi knew that sacred writings had to be carefully preserved from those who “seek to destroy the things of God” (2 Nephi 26:17). Enos wrote that Lamanite enemies, “swore in the wrath that, if it were possible, they would destroy our records and us, and also all the traditions of our fathers" (Enos 1:14; emphasis added), and the Book of Mormon shows that it was only through painstaking labor that they were able to be successful in doing so.

Demonstrating that the destruction of records was no idle concern, an instance of actual destruction of records is recorded in the book of Alma. After casting out the righteous men, the city’s wicked inhabitants burned women and children, along with their sacred records (Alma 14:7–8).

Not long before the annihilation of the Nephite nation, Mormon hid up all the sacred writings of his people in his possession, “for the Lamanites would destroy them” (Mormon 6:6).1 In ancient Mesoamerican the practice deliberately altering or destroying historical materials is well known.

Spanish Destruction of Aztec Histories

Attempts to destroy records of the past have a long and tragic history. According to H. B. Nicholson,

Deliberate destruction of records frequently accompanied pre-hispanic as well as post-Conquest military takeovers. As always, one of the principles prizes of military victory was the past (cf. Orwell’s ‘who controls the past controls the future; who controls the present controls the past.’), and conscious alteration of existing records for political advantage in the wake of conquests and related upheavals must have been common and creates problems in long range chronological interpretation.2

The Spanish Conquest led to the irreparable loss of valuable historical knowledge about the pre-Columbian past. Friar Diego Duran, who tried to reconstruct the history of the Mexica, wrote with frustration, “Some early friars burned ancient books and writings and thus they were lost. Then too, the old people who could write these books are no longer alive to tell of the settling of this country, and it was they whom I would have consulted for my chronicle.”3

The sparse details concerning Tlaxcaltecan rulers given in the Anonimo Mexicano, a document written decades after the Conquest, sadly points to the dearth of historical knowledge caused by the loss of such records. In a passage which speaks of earlier kings, the writer recounts,

He was called Cuauhtzinteuctli, grandson of the ruler of Acolhua. And he made himself the ruler.And this ruler's accomplishments were not written, because the books about his rulership perished. Then he was succeeded by Ilhhuicamina. After he died, Matlaccoatl followed behind him and was made ruler. After this ruler died, a son called Tezcacoatl received the rulership. After this Tezcacoatl died, one named Tezcapoctli ruled. After this Tezcapoctli died, the lord Teotlehuac followed him. But the accomplishments of all these lords are not found in the painted books. When the Spanish entered, they destroyed all these books.4

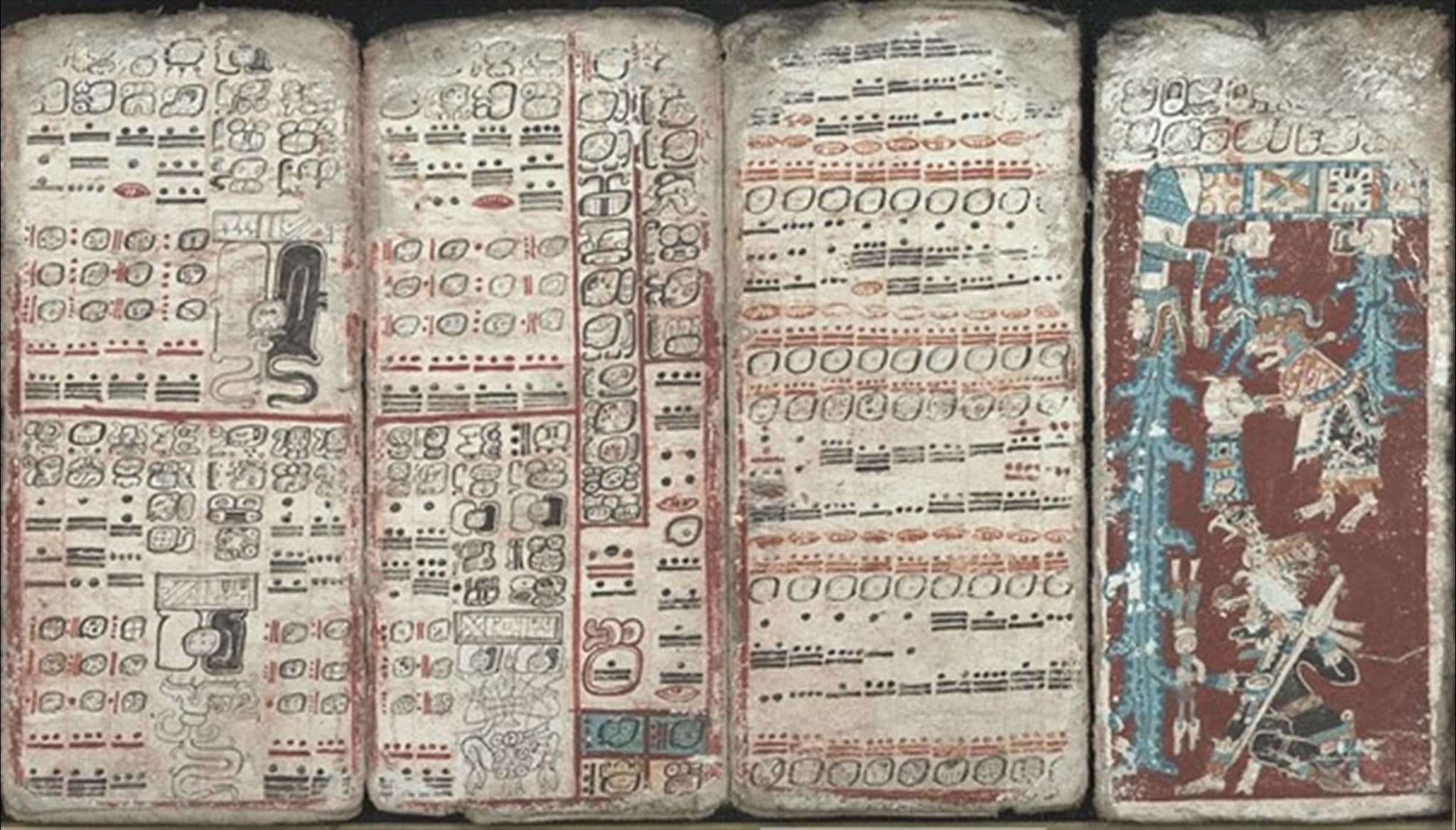

Spanish Destruction of Maya Records

In Yucatan, Bishop Diego de Landa directed and oversaw the destruction of numerous Maya codices of which less than a handful survive today. He wrote:

These people also made use of certain characters or letters, with which they wrote in their books their ancient matters and their sciences, and by these drawings and by curious signs in these drawings, they understood their affairs and made others understand them and taught them. We found a large number of books in these characters and, as they contained nothing in which there were not to be seen superstition and lies of the devil, we burned them all, which they regretted to an amazing degree, and which caused them much affliction.5

According to Bernardo de Lizana, Landa discovered a cache of codices in a cave.

He collected the books and the ancient writing and he commanded them burned and tied up. They burned many historical books of the ancient Yucatan which told of its beginning and history, which were of much value if, in our writing, they had been translated because today there would be something original. At best there is no great authority for more than the traditions of these Indians.6

Spanish clergy and historians lamented the willful destruction of such records.

Afterwards some of our friars understood and knew how to read them, and even wrote them, but because in these books were mixed many things of idolatry, they burned almost all of them, and thus was lost the knowledge of many ancient matters of that land which by them could have been known.7

Jose de Acosta wrote,

In the province of Yucatan, where is the so-called Bishopric of Honduras, there used to exist some books of leaves, bound or folded after a fashion, in which the learned Indians kept the distribution of their times and the knowledge of plants, animals, and other things of nature and the ancient customs, in a way of great neatness and carefulness. It appeared to a teacher of doctrine that all this must be to make witchcraft and magic art; he contended that they should be burned and those books were burned and afterwards not only the Indians but many eager-minded Spaniards who desired to know the secrets of that land felt badly. The same thing has happened in other cases where our people, thinking that all is superstition, have lost many memories of ancient and hidden things which they might have used to no little advantage. This follows from a stupid zeal, when without knowing or even wishing to know the things of the Indians, they say as in the sealed package, that everything is sorcery and that the peoples there are only a drunken lot and what can they know or understand. The ones who have wished earnestly to be informed of these have found many things worthy of consideration.8

Destruction of Pre-Columbian Records by the Aztecs

Attempts to alter or erase a knowledge of the past occurred in pre-Columbian times as well. Native accounts from the Valley of Mexico indicate that during the reign of Itzcoatl (1427–1440) many Aztec records were deliberately burned by Aztecs rulers themselves for ideological purposes. The rulers at Tenochtitlan rewrote their own history and destroyed earlier versions.

According to Doris Heyden, “The Aztec had to be put in a favorable light in order to eradicate their early and probably undistinguished past.”9 The Florentine Codex states, “A council of rulers of Mexico took place. They said: ‘It is not necessary for all the common people to know of the writings; government will be defamed, and this will only spread sorcery in the land; for it containeth many falsehoods.’”10 Joyce Marcus suggests that these burned histories likely “contained the deeds of previous rulers, their genealogies, and their relations with neighboring peoples.”11 Such records conflicted with the new propaganda promoted by Aztec elite.

In the official Mexica version of the conquest of Azcopalzalco, the Mexica did not acknowledge the substantial aid they received from their allies, the Alcohua of Texcoco; in fact, they neglected to mention that they had had any help. To legitimize their new prominence, the Mexica also needed to establish that they had had a glorious and worthy heritage; thus, they decided to claim descent from the last great civilization, that of the Toltec. They also decided to elevate their patron deity of war, Huitzilopochtli, to a level above that of the other deities populating the cosmos …. Itzcoatl thought that the Mexica’s historical archives were no longer appropriate to their new-found prominence, so he burned them and wrote a new history that was more in line with current needs.12

“The famous burning of the books by (Aztec) Itzcoatl,” wrote Davies, “was hardly an isolated case and the Maya were surely not alone in ritually destroying their carved texts.” 13

Destruction of Pre-Columbian Records by the Maya

The pre-Columbian Maya also destroyed codices and carved texts on monuments. Nigel Davies believed that codices “were destroyed at intervals and history was then rewritten to suit the ruler of the day.”14 Monuments and Stela were defaced and destroyed throughout most of Mesoamerican history. Such monuments, written on stone, however, constituted only a small part of what once must have been a robust and widespread literary tradition of records written on perishable materials. Mayanist Michael Coe wrote that the end of the Classic Period of Maya culture sadly saw the destruction of many such records.

It was not just the “stela cult”—the inscribed glorification of royal lineages and their achievements—that disappeared with the [Maya] collapse, but an entire world of esoteric knowledge, mythology, and ritual. Much of the elite cultural behavior … such as the complex underworld mythology and iconography found on Classic Maya funerary ceramics, failed to re-emerge with the advent of the Post-Classic era, and one can only conclude that the royalty and nobility, including the scribes who were the repository of so much sacred knowledge, had “gone with the wind.” They may well have been massacred by an enraged populace, and their screen-fold books consumed in a holocaust similar to that carried out centuries later by Bishop Landa.15

Conclusion

The Lamanites had rival traditions which conflicted with those held by the Nephites (Mosiah 10:12–17; Alma 54:16–18; 3 Nephi 3:10).16 Nephites dissenters, some of whom found value in keeping records for economic reasons, were not interested in preserving much else from Nephite tradition (Mosiah 24:5–7). Additionally, the Lamanites, in their campaign of cultural genocide, actively sought to destroy all Nephite records and traditions when they could (Enos 1:14; Mormon 6:6).

Thus, based on the text itself, readers should be very hesitant to expect clear traces of Nephite culture to readily turn up in the archaeological and historical record. Those Nephite texts that weren’t destroyed by the Lamanites or other cultures would have been hidden up in the earth, to come forth at some future day as guided by the hand of the Lord.

The known practice of eradicating cultures found in later stages of Mesoamerican history proves that the Book of Mormon’s claims on this matter shouldn’t be taken as fanciful. Furthermore, although intentional cultural annihilation is a well-known fact among historians, that doesn’t mean that it is widely familiar to non-specialists. It is therefore questionable whether Joseph Smith in 1829 would have even been aware of this historical phenomenon.

John L. Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex: An Ancient American Book (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book and the Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2013), 184–232.

John L. Sorenson, Images of Ancient America: Visualizing Book of Mormon Life (Provo, UT: Research Press, 1998), 158–163.

John L. Sorenson, “The Book of Mormon as a Mesoamerican Record,” in Book of Mormon Authorship Revisited, ed. Noel B. Reynolds (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1997), 391–521.

- 1. For more examples of hidden records and relics among Book of Mormon peoples, see Evidence Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Ancient Hidden Records,” November 18, 2020, online at evidencecentral.org.

- 2. H. B. Nicholson, “Western Mesoamerica: 900–1620,” in Chronologies in New World Archaeology, ed. R. E. Taylor and Clement W. Meighan (New York, NY: Academic Press, 1978), 320.

- 3. Diego Duran, The History of the Indies of New Spain. ed. and trans. Doris Heyden (Norman and London: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994), 20.

- 4. Richley H. Crapo and Bonnie Glass-Coffin, eds., Anonimo Mexicano (Logan, UT: Utah State University Press, 2005), 26.

- 5. Alfred M. Tozzer, ed., Landa Relacion de las Cosas de Yucatan (Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, 1941), 169.

- 6. Tozzer, Landa Relacion de las Cosas de Yucatan, 78.

- 7. Alonzo de San Juan Ponce, in Tozzer, Landa Relacion de las Cosas de Yucatán, 78.

- 8. Jose de Acosta, in Tozzer, Landa Relacion de las Cosas de Yucatán, 78.

- 9. Heyden, The History of the Indies of New Spain, 81, note 7.

- 10. Charles E. Dibble and Arthur J. O. Anderson, eds., The Florentine Codex. Book 10: The People (Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research and the Museum of New Mexico, 1961), 191.

- 11. Joyce Marcus, Mesoamerican Writing Systems: Propaganda, Myth, and History in Four Ancient Civilizations (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992), 146.

- 12. Marcus, Mesoamerican Writing Systems, 148–149.

- 13. Nigel Davies, “The Aztec Concept of History: Teotihuacan and Tula,” in The Native Sources and the History of the Valley of Mexico, ed. Jacqeline de Durand-Forest (Oxford: BAR, 1984), 207.

- 14. Davies, “The Aztec Concept of History,” 207.

- 15. Michael D. Coe, The Maya, 5th ed. (London: Thames and Hudson, 1993), 128.

- 16. For more evidence of competing historical and political narratives among Lehi’s descendants, see Noel B. Reynolds, “Nephi’s Political Testament,” in Rediscovering the Book of Mormon: Insights You May Have Missed Before, ed. John L. Sorenson and Melvin J. Thorne (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1991), 221; Noel B. Reynolds, “The Political Dimension in Nephi’s Small Plates,” BYU Studies Quarterly 27, no. 4 (1987): 15–37.