Evidence #6 | September 19, 2020

Book of Mormon Evidence: Chiasmus Overview

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

Abstract

The Book of Mormon’s pervasive and often complex chiastic structures are better explained as having come from various ancient writers than as having been created by Joseph Smith, especially under the circumstances described by the witnesses of the translation.Introduction

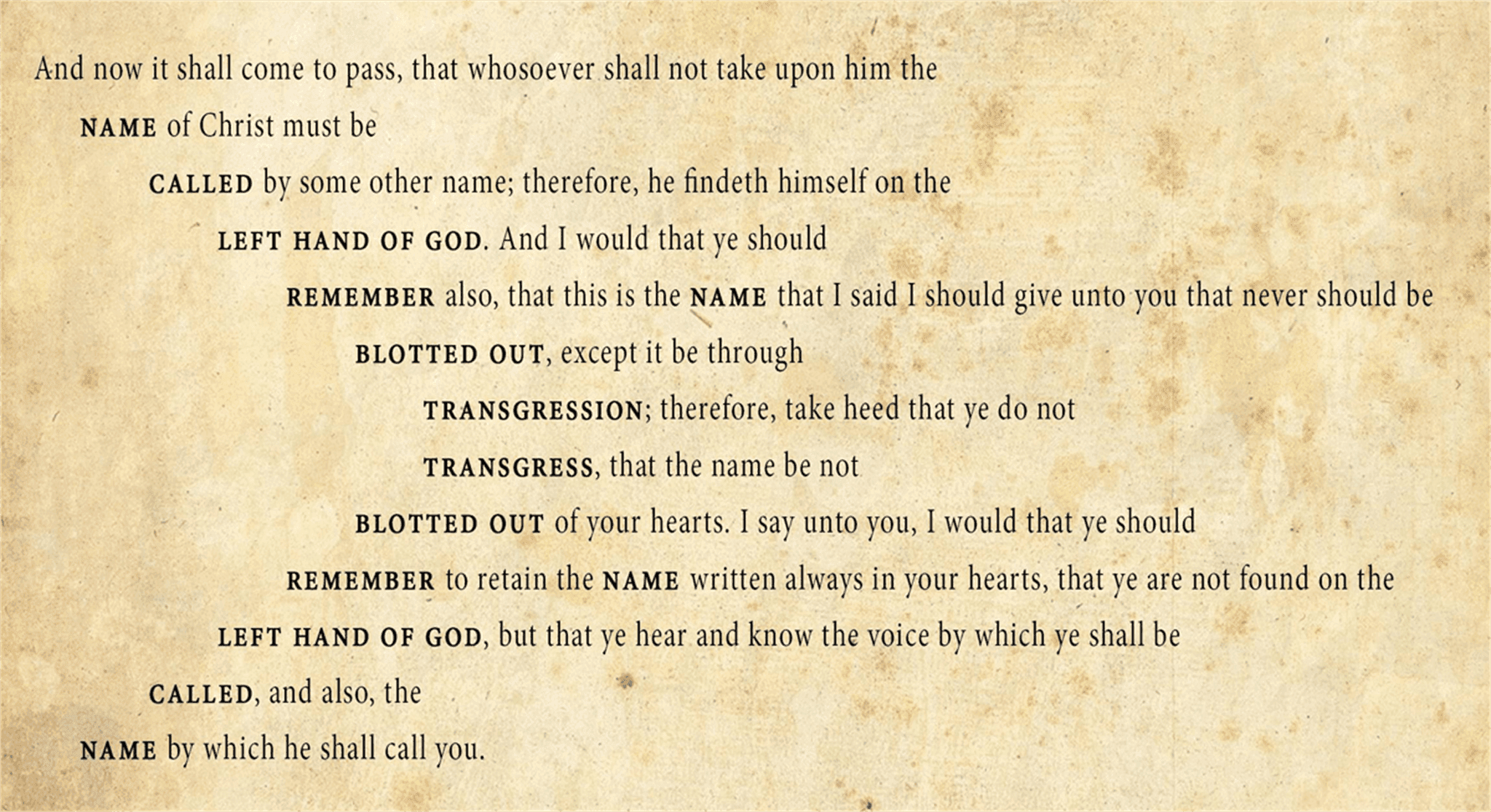

Chiasmus is a type of literary structure that has been used in both poetry and prose for thousands of years in a variety of cultures and languages. It can be described as an inverted parallelism, where key words, phrases, or ideas in the first half of the structure are reversed and repeated in the second half. For example, Jesus taught that “many that are first shall be last; and the last shall be first” (Matthew 19:30). To help readers keep track of corresponding elements, chiasms are often formatted as follows:

A | many that are first | |

B | shall be last; | |

B | and the last | |

A | shall be first. | |

Not all chiasms, however, are so simple or follow precisely the same pattern. This more developed chiasm from Christ’s Sermon on the Mount has a 7-layer structure:

A | Ye shall know them by their fruits. | ||||||

B | Do men gather grapes of thorns, or figs of thistles? | ||||||

C | Even so every good tree | ||||||

D | bringeth forther good fruit; | ||||||

E | But a corrupt tree | ||||||

F | bringeth forth evil fruit. | ||||||

G | A good tree | ||||||

F | cannot bring forth evil fruit | ||||||

E | neither can a corrupt tree | ||||||

D | bring forth good fruit. | ||||||

C | Every tree | ||||||

B | that bringeth not forth good fruit is hewn down, and cast into the fire. | ||||||

A | Wherefore by their fruits ye shall know them. (Matthew 7:16–20) | ||||||

Notice that in this chiasm the middle element (G) stands on its own without being repeated. Moreover, instead of being similar or the same, elements C are related but opposite concepts (the first instance discusses men who gather fruit for harvest and the second mentions the fruit-bearing trees being cast into a fire to be destroyed). Thus, while the fundamental parallel structure (inverted repetition) is always present, chiasmus can be implemented in a variety of nuanced ways.

Criteria for Identifying Chiasmus

In the last fifty years, scholars in many fields have found, or proposed to find, chiasms in ancient Ugaritic, Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek, Latin, and Mesoamerican writings, as well as in Medieval, Renaissance, Arabian, Hindu, and modern literatures, including Shakespeare, Montaigne, and beyond. It has also been abundantly identified in the Book of Mormon.1

Some researchers have overzealously engaged in what can be called chiasmania—seeing chiasmus everywhere in writings, whether it was likely intended or not.2 Others, meanwhile, have argued that chiasmus may have occurred by mere chance in the Book of Mormon or in other texts.3 These opposing perspectives attest to the need for reliable criteria to distinguish between chiastic patterns that were most likely deliberate creations and those that occur randomly. Fortunately, a number of scholars have addressed this issue and their efforts have now been brought together for easy comparison on the Chiasmus Resources website.4 The most widely agreed upon standards can be summarized as follows:

- Chiasms should conform to natural literary boundaries.

- A climax or turning point should usually be found at the center.

- A chiasm’s inverted pattern should display a relatively well-balanced symmetry.

- Most of a chiasm’s repeated words or ideas should have significant meaning.

- Chiasms should manifest little, if any, extraneous repetition or divergent material.

- Chiastic structures should typically not compete or overlap with other strong literary forms.

While these criteria are helpful, the evaluation of chiastic structures necessarily remains an interpretive exercise. Hence, rather than advancing absolute, final judgments, those proposing chiastic arrangements in a text should recognize that all “chiastic passages manifest varying degrees of chiasticity.”5 It is even possible that different individuals will agree generally that a passage is chiastic, but may disagree on the particulars of its arrangement. In the final analysis, one can never definitively prove that an author intended to implement a chiasm. Yet, when a given proposal meets many or all of the most widely accepted standards, a chiasm’s likelihood of being intentional significantly increases.

In this regard, some researchers have sought to reduce the role of reader subjectivity by using statistical methods to evaluate chiastic patterns.6 These methods are able to determine that some proposed chiastic patterns were very likely to have been created deliberately, but they cannot prove if others which, statistically speaking, could plausibly have occurred by chance, actually did occur by chance.7 As such, statistical analysis is best used together with additional criteria to evaluate the merits of any proposed chiasm.8

Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon

The presence of chiasmus in the Book of Mormon was discovered by John W. Welch in 1967 while he was serving as a missionary in Germany.9 After returning home from his mission, Welch further developed and eventually published his findings,10 which helped initiate a wave of new literary studies on the Book of Mormon, including many more explorations of its use of chiasmus.11 Since then, various scholars and researchers have proposed hundreds of chiastic structures in its pages (see Chiasmus Resources).

These chiasms vary in length, complexity, and persuasiveness, but many of them measure up well against even the strictest sets of criteria. For example, statistical analysis conducted by Boyd and Farrell Edwards indicates that some of the Book of Mormon’s chiasms—namely Alma 36, Mosiah 3:18–19, Mosiah 5:10–12, and Helaman 6:9–11—are very unlikely to have occurred randomly or by accident.12 More recently, Dennis Newton has applied the same statistical technique to 15 chiasms in 1 and 2 Nephi, finding “there is strong likelihood that nine of these were composed intentionally and that it is probable that another three were intentional.”13

Overall, the Book of Mormon manifests a remarkable degree of chiasticity. Even if some of its proposed chiasms were not deliberately intended by the text’s authors, there are so many good candidates that it is hard to see them collectively as having been produced unintentionally or by random chance. For a comprehensive list of formatted chiasms in the text, see the Appendix.

Could Joseph Smith Have Known about Chiasmus in 1829?

Some Renaissance authors,14 especially William Shakespeare,15 made use of chiasmus in English texts. And to varying degrees the inverted structure persisted into the 19th century.16 However, discussions of chiasmus (or related concepts) seem to crop up rather infrequently in either the literature of Joseph Smith’s day or in the extensive volumes of literary criticism that have since been published about the literature of his time.17 Even when chiasmus has been identified in 18th or early-19th century texts, most proposed instances are simple A-B-B-A patterns.18 Some examples of macro chiastic structures (sometimes referred to in literary studies as “ring compositions” or “ring forms”) are also found in texts from that era,19 but such large structures are rather different from most of the proposed chiasms in the Book of Mormon.20

It is also possible that Joseph Smith could have learned about chiasmus from emerging biblical studies, but the relevant research was primarily being published across the ocean in London. In his investigation of this subject over the years, Welch has found no evidence that the published research had “reached America, let alone Palmyra or Harmony, in the 1820s.”21 As close as one can find is a brief summary of John Jebb’s 1820 work that was included in the second, 1825 edition of Thomas Hartwell Horne’s massive introduction to the critical study of the Bible, printed both in London and Philadelphia.22 Yet, as Welch has argued, it is unlikely that Joseph Smith ever came across this summary.23

Finally, some may assume that Joseph Smith simply noticed chiasmus in the Bible or in Shakespeare’s writings or from some other source. This possibility can never be completely ruled out, but it should be remembered that anything much more complex than chiastic couplets are typically not consciously noticed by readers. It took over 130 years for anyone to draw attention to the pervasive, complex chiastic structures in the Book of Mormon. And likely millions of people have read extensively from the Bible without ever recognizing its many chiasms. It is simply not a literary structure that readers—especially Western readers—are prone to consciously notice without it being pointed out to them.24

What Does Chiasmus Prove in the Book of Mormon?

The Book of Mormon indicates that it was written in an Egyptian script by ancient American prophets who preserved the literary tradition of their Hebrew ancestors. That being the case, it is noteworthy that chiasmus shows up anciently in Egyptian texts,25 and it was a “dominant, if not essential, element of Hebrew writing” in the centuries surrounding Lehi’s day.26 Preliminary evidence also suggests that chiasmus was prominent in early documents from Mesoamerica27—where many Latter-day Saint scholars and researchers believe the primary events recorded in the Book of Mormon took place. The large quantity of chiastic structures identified in the Book of Mormon is therefore what readers might expect to find, based on the text’s own claims about its origins and Joseph Smith’s understanding of its geographical setting.

On the other hand, the Book of Mormon’s pervasive chiastic structures seem to be out of place for an early 19th century text. Perhaps further research will someday demonstrate that other texts from that literary era are comparable in their quantity and variety of complex, multi-layered chiasms, but until then, the Book of Mormon appears to have a remarkable—and perhaps unparalleled—degree of overall chiasticity for its time.

It should also be remembered that multiple witnesses described the Book of Mormon, a notably lengthy and complex book, as having been rapidly dictated (historical evidence suggests it was completed in approximately 60 working days28) by an uneducated farmer who didn’t make use of any outlines, reference materials, working notes, or substantive revisions.29 How an inexperienced author like Joseph Smith could have implemented so many impressive chiastic structures under such constraining circumstances remains to be explained by naturalistic theories about the text’s origins.30 At the very least, the text’s extraordinary chiasticity places a heavy burden on such theories, while at the same time helping affirm the Book of Mormon’s claimed ancient origins.

Donald W. Parry, Poetic Parallelisms in the Book of Mormon: The Complete Text Reformatted (Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2007), 565.

Robert F. Smith, “Assessing the Broad Impact of Jack Welch’s Discovery of Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 16, no. 2 (2007): 68–73, 98–99.

Boyd F. Edwards and W. Farrell Edwards, “Does Chiasmus Appear in the Book of Mormon by Chance?” BYU Studies Quarterly 43, no. 2 (2004): 103–130.

John W. Welch, “What Does Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon Prove?” in Book of Mormon Authorship Revisited: The Evidence for Ancient Origins, ed. Noel B. Reynolds (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1997), 199–224.

John W. Welch, “Criteria for Identifying and Evaluating the Presence of Chiasmus,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 14, no. 2 (1995): 1–14.

John W. Welch, “Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon,” Ensign, February 1972, online at ChurchofJesusChrist.org.

Do to formatting constraints when transitioning to the new website, the formatted chiastic structures that were previousyly presented in this appendix have been removed. Those looking for a large survey of many chiastic structures found in the Book of Mormon can consult the following source: Donald W. Parry, Poetic Parallelisms in the Book of Mormon: The Complete Text Reformatted (Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2007). A list of all chiasms can be found specifically on page 565.

- 1. See “Chiasmus Index,” online at chiasmusresources.org.

- 2. See, for example, various proposals at latterdaychiasmus.com or davidicchiasmus.com.

- 3. See, for example, Brent Lee Metcalfe, “Apologetic and Critical Assumptions about Book of Mormon Historicity,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 26, no. 3 (1993): 162–171. For a response to Metcalfe, see William J. Hamblin, “An Apologist for the Critics: Brent Lee Metcalfe’s Assumptions and Methodologies,” Review of Books on the Book of Mormon, 6, no. 1 (1994): 493–499. See also Boyd F. Edwards and W. Farrell Edwards, “Does Chiasmus Appear in the Book of Mormon by Chance?” BYU Studies Quarterly 43, no. 2 (2004): 105–106. For a wide-ranging collection of discussions about the phenomenon of chiasmus in general, see Boris Wiseman and Anthony Paul, ed., Chiasmus and Culture (New York, NY: Berghahn Books, 2014).

- 4. See “Criteria Chart,” online at chiasmusresources.org.

- 5. John W. Welch, “Criteria for Identifying and Evaluating the Presence of Chiasmus,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 14, no. 2 (1995): 14.

- 6. See Boyd F. Edwards and W. Farrell Edwards, “Does Chiasmus Appear in the Book of Mormon by Chance?” BYU Studies 43, no. 2 (2004): 103–130; Boyd F. Edwards and W. Farrell Edwards, “When are Chiasms Admissible as Evidence?” BYU Studies 49, no. 4 (2010): 131–154; Dennis Newton, “Nephi’s Use of Inverted Parallels,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 22 (2016): 79–106; Yehuda T. Radday, “Chiasmus in Hebrew Biblical Narrative,” in Chiasmus in Antiquity: Structures, Analysis, Exegesis, ed. John W. Welch (Hildesheim, GER: Gerstenberg Verlag, 1981; reprint Provo, UT: Research Press, 1999), 50–117. For recent statistical linguistic research aimed more generally at detecting chiasmus in texts, see Marie Dubremetz and Joakim Nivre, “Rhetorical Figure Detection: Chiasmus, Epanaphora, Epiphora,” Frontiers in Digital Humanities 5 (2018); Marie Dubremetz and Joakim Nivre “Machine Learning for Rhetorical Figure Detection: More Chiasmus with Less Annotation,” Proceedings of the 21st Nordic Conference of Computational Linguistics, May 2017, 37–45; Marie Dubremetz and Joakim Nivre, “Syntax Matters for Rhetorical Structure: The Case of Chiasmus,” Proceedings of the Fifth Workshop on Computational Linguistics for Literature, 2016, 47–53; Marie Dubremetz and Joakim Nivre, “Rhetorical Figure Detection: the Case of Chiasmus,” Proceedings of the Fourth Workshop on Computational Linguistics for Literature, 2015, 23–31.

- 7. See Edwards and Edwards, “Does Chiasmus Appear,” 109: “Though a moderate or a large value of P for a passage implies that its chiastic structure could easily be replicated by random rearrangements, this does not imply that chiastic structure is likely to have been unintentional on the part of the author. Moderate and large values of P say absolutely nothing about intentionality. The author of a passage with a moderate or large value of P may well have intentionally invoked the chiastic form in composing the passage, but such a value simply provides no evidence that she did, nor does it provide evidence that she did not.” See also, Edwards and Edwards, “When are Chiasms Admissible,” 141, 154: “Some chiasms with P > 0.05 have literary value and might well have appeared by design. … Failing our statistical admissibility test does not mean that a chiasm was not intentional. For such chiasms, other compensating merits and other analytical approaches, such as Welch’s fifteen criteria, can be considered in reaching a judgment about intentionality.” Newton, “Nephi’s Use of Inverted Parallels,” 88 emphasizes this same point: “this does not mean the lower probability candidates were not written intentionally.” This is inherent in statistical reasoning, which is why a p-value < 0.05 yields the conclusion to “reject the null-hypothesis” (that X occurs by random chance), but a p-value > 0.05 only leads to the conclusion “fail to reject the null-hypothesis” rather than simply accepting the null-hypothesis.

- 8. For an attempt to employ statistical methods in conjunction with additional criteria, see Newton, “Nephi’s Use of Inverted Parallels,” 79–106.

- 9. For Welch’s own recounting of this story, see John W. Welch, “The Discovery of Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon: Forty Years Later,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 16, no. 2 (2007): 74–87, 99; John W. Welch, “Forty-Five Years of Chiasmus Conversations: Correspondence, Criteria, and Creativity,” 2012 FairMormon Conference address, online at fairmormon.org. See also, Book of Mormon Central, “How Was Chiasmus Discovered in the Book of Mormon? (Mosiah 5:11),” KnoWhy 353 (August 16, 2017).

- 10. For Welch’s first publication on chiasmus, see John W. Welch, “Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon,” BYU Studies 10, no. 1 (1969): 69–84.

- 11. See Robert F. Smith, “Assessing the Broad Impact of Jack Welch’s Discovery of Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 16, no. 2 (2007): 68–73, 98–99. For a broad survey of publications on chiasmus generally, see “Chiasmus Bibliography,” online at chiasmusresources.org.

- 12. Edwards and Edwards, “Does Chiasmus Appear,” 125.

- 13. Newton, “Nephi’s Use of Inverted Parallels,” 98.

- 14. See William E. Engel, Chiastic Designs in English Literature from Sidney to Shakespeare (Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, 2009); Jeffrey Bilbro, “The Form of the Cross: Milton’s Chiastic Soteriology,” Milton Quarterly 47, no. 3 (2013): 127–148; William E. Engel, “John Milton’s Recourse to Old English: A Case Study in Renaissance Lexicography,” LATCH 1 (2008): 19–20; Dunya Muhammad Miqdad I’jam and Zahraa Adnan Fadhil, “Chiasmus as a Stylistic Device in Donne’s and Vaughan’s Poetry,” Journal of Education and Practice 7, no. 26 (2016): 43–52.

- 15. See James E. Ryan, Shakespeare’s Symmetries: The Mirrored Structure of Action in the Plays (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2016); William L. Davis, “Structural Secrets: Shakespeare’s Complex Chiasmus,” Style 39, no. 3 (2005): 237–258; William L. Davis, “Better a Witty Fool than a Foolish Wit: the Art of Shakespeare’s Chiasmus,” Text and Performance Quarterly 23, no. 4 (2003): 311–330; Ira Clark, “‘Measure for Measure’: Chiasmus, Justice, and Mercy,” Style 35, no. 4 (2001): 659–680.

- 16. See Richard Copley, The Formal Center in Literature: Explorations from Poe to the Present (Rochester, NY: Camden House, 2018); Mark J. Bruhn, “William Wordsworth: The Prelude (1798, 1799, 1805, 1850),” in Handbook of British Romanticism, ed. Ralf Haekel (Boston, MA: De Gruyter, 2017), 399–402; Sanford Budick, “Chiasmus and the Making of Literary Tradition: The Case of Wordsworth and ‘The Days of Dryden and Pope’,” ELH 60, no. 4 (1993): 961–987; Keith G. Thomas, “Jane Austen and the Romantic Lyric: Persuasion and Coleridge’s Conversation Poems,” ELH 54, no. 4 (1987): 893–924; Richard Kopley, “Chiasmus in Walden,” The New England Quarterly 77, no. 1 (2004): 115–121.

- 17. Besides the relatively sparse results gained from searching for various chiasmus-related terms in 19th century texts (or in the subsequent literature about those texts) in online search engines and databases, fairly recent discussions of this topic often hint that formal knowledge or discussion about chiasmus was sparse in Joseph Smith’s day. For example, Davis, “Structural Secrets,” 237 remarks that “even though these [chiastic] patterns were commonly used in earlier centuries, an awareness of the large-scale biblical patterns appears to have begun fading into the background with the passage of time, and English Renaissance books on rhetoric and poetry remain silent on the subject.”

- 18. For example, Henry David Thoreau’s frequent use of simple chiasms (with an A-B-B-A pattern) seems somewhat puzzling to Richard Kopley, who writes: “Precisely how Thoreau learned his chiastic skill is uncertain.” This uncertainty would not likely exist if chiasmus was a standard part of 19th century literary instruction or a matter frequently brought up in the literary criticism of the day. As a possibility, Kopley proposed that perhaps Thoreau learned of chiasmus from “his rhetoric textbook at Harvard, Richard Whately’s Elements of Rhetoric, which discusses the ABBA pattern.” Kopley, “Chiasmus in Walden,” 120. Yet, not only does Whately’s text (published in 1832) fail to explicitly describe the A-B-B-A pattern, it doesn’t even show any examples of it. Another possibility presented in the footnote is that Thoreau learned of chiasmus from George Campbell, The Philosophy of Rhetoric, 2 vols. (London: W. Strahen, and T. Cadell, and W. Creech, 1776), 2:353–355. This seems to be a much more likely option. It provides several examples of chiasmus, which it refers to as an “inverted” arrangement of repeated words (p. 354). This widely influential text could indeed have been a source for Thoreau or other late-18th and 19th century authors. However, it appears that its treatment of chiasmus never goes beyond simple couplets with the A-B-B-A formula.

- 19. Not all proposals of what has been called “ring composition” are necessarily macro structures (sometimes ring composition can refer to smaller chiasms), but most examples tend to involve much larger amounts of text than most of the proposed chiasms in the Book of Mormon.

- 20. For a brief discussion of ring composition in relation to the Book of Mormon, see Benjamin McGuire, “The Book of Mormon as a Communicative Act: Translation in Context,” 2016 Fair Mormon Conference presentation, online at fairmormon.org. For proposals of ring composition in a variety of ancient and modern texts, see Mary Douglas, Thinking in Circles: An Essay on Ring Composition (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007); William L. Benzon, “Ring Composition: Some Notes on a Particular Literary Morphology,” online at academia.edu. For a cautionary critique of ring composition proposals, see Joseph A. Dane, “The Notion of Ring Composition in Classical and Medieval Studies: A Comment on Critical Method and Illusion,” Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 94, no 1. (1993): 61–67. See also Welch, “Criteria for Identifying and Evaluating the Presence of Chiasmus,” 4: “The degree of certainty about the presence of chiasmus in a text usually varies in inverse proportion to the total length of the text. In other words, the more spread out the proposed chiasm, the less certain the fact of its chiasticity becomes, except in remarkable circumstances. Hence, the more extended the proposed chiasm, the greater will be the need for multiple corroborating factors before the passage can be meaningfully described as chiastic.”

- 21. John W. Welch, “How Much Was Known about Chiasmus in 1829 When the Book of Mormon Was Translated?” FARMS Review 15, no. 1 (2003): 76.

- 22. In 1825, Horne published the 4th edition of his three-volume Introduction to the Critical Study and Knowledge of the Holy Scriptures (Philadelphia, PA: Littell, 1825). It seems to have been the first American publication to mention Jebb’s work on chiasmus. A 6th edition of this biblical encyclopedia was published in 1828, with changes mostly to its typesetting. In 1827, Horne published the 2nd edition of a condensed version of his encyclopedia, called Compendious Introduction to the Study of the Bible (New York, NW: Arthur), and in 1829 he published a 3rd edition. These works contained an even briefer mention of Jebb’s chiasmus-related writings (p. 191 in the 1827 edition and p. 144 in the 1829 edition). These encyclopedic volumes never discussed Boys’ research on chiasmus in the Psalms and in the New Testament, and it appears that only Horne’s 1825 edition was published in America. This information corrects and expands what was known in the 1960s and 1970s about these obscure sources. See Welch, “How Much Was Known about Chiasmus in 1829?” 63–68.

- 23. In its 28-page chapter on Hebrew poetry, Horne’s publication contains only three short examples of “parallel lines introverted” in the Old Testament and two A-B-B-A examples in the New Testament. Horne, Introduction to the Critical Study, 456–457, 467. Moreover, as Welch has observed, “Horne’s work is massively intimidating … [and] mentions virtually everything in the then-known world of biblical scholarship. Merely locating the discussion of chiasmus, epanodos, or introverted parallelism in this vast array is difficult, even when one knows what to look for. Welch, “How Much Was Known about Chiasmus in 1829?” 78. Thus, while it is technically possible that Joseph Smith could have stumbled upon a summary of the London-based research, it seems unlikely that he actually did.

- 24. See John W. Welch, “What Does Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon Prove?” in Book of Mormon Authorship Revisited: The Evidence for Ancient Origins, ed. Noel B. Reynolds (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1997), 219: “On the other hand, it may be suggested that Joseph Smith could have sensed intuitively the nature and importance of chiasmus as a reader of the Bible. This factor, however, is not very persuasive for several reasons. First, it is rarely the case that the Hebrew or Greek chiastic patterns have been preserved rigorously through the process of English translation. In many cases, the English translators preferred to correct the inverted verb orders and to restructure them in more natural English word orders. Moreover, many biblical scholars who work regularly with the texts do not naturally write in chiastic forms themselves, and many of them are not aware, either consciously or subconsciously, of the chiastic structure of biblical text. When I presented a paper on chiasmus in biblical law to a conference of the Jewish Law Association held in Boston, several distinguished Jewish scholars were quite astonished that a Gentile could show them something as distinctive and remarkable in their own Torah as the arrangements in Leviticus 24 and elsewhere. I was not the first to discover chiasmus in Leviticus 24, but the present point is simply to show that structures such as these do not naturally jump out at readers—even at those who read this text regularly and assiduously, and in Hebrew—without someone pointing these patterns out to them. Consequently, it assumes too much to believe that the young Joseph Smith’s reading of the King James English adequately explains the extensive and objectively rigorous instances of chiasmus in the Book of Mormon.”

- 25. See “Ancient Egyptian Texts,” online at chiasmusresources.org.

- 26. Welch, “What Does Chiasmus in the Book of Mormon Prove?” 213.

- 27. See Book of Mormon Central, “Was Chiasmus Known to Ancient American Writers? (Alma 29:4),” KnoWhy 346 (July 31, 2017); Kerry M. Hull and Michael D. Carrasco, eds., Parallel Worlds: Genre, Discourse, and Poetics in Contemporary, Colonial, and Classic Maya Literature (Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado, 2012); Allen J. Christenson, “The Use of Chiasmus in Ancient Mesoamerica” (FARMS Preliminary Report, 1988); Allen J. Christenson, “Chiasmus in Mayan Texts,” Ensign, October 1988, online at churchofjesuschrist.org;

- 28. See John W. Welch, “Timing the Translation of the Book of Mormon: ‘Days [and Hours] Never to Be Forgotten’,” BYU Studies Quarterly 57, no. 4 (2018): 10–50; Book of Mormon Central, “Why Is the Timing of the Book of Mormon’s Translation So ‘Marvelous’? (2 Nephi 27:26),” KnoWhy 506 (March 15, 2019).

- 29. See John W. Welch, “The Miraculous Timing of the Translation of the Book of Mormon,” in Opening the Heavens: Accounts of Divine Manifestations, 1820–1844, ed. John W. Welch, 2nd edition (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and BYU Press, 2017), 143, 168; Daniel C. Peterson, “Editor’s Introduction—Not So Easily Dismissed: Some Facts for Which Counterexplanations of the Book of Mormon Will Need to Account,” FARMS Review 17, no. 2 (2005): xiii–xvi; Royal Skousen, “How Joseph Smith Translated the Book of Mormon: Evidence from the Original Manuscript,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 7, no. 1 (1998): 24.

- 30. For a brief summary of the Book of Mormon’s various types of complexity, see Melvin J. Thorne, “Complexity, Consistency, Ignorance, and Probabilities,” in Book of Mormon Authorship Revisited: The Evidence for Ancient Origins, ed. Noel B. Reynolds (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1997), 179–193.