KnoWhy #752 | September 17, 2024

Why Was Zemnarihah Executed by Hanging?

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

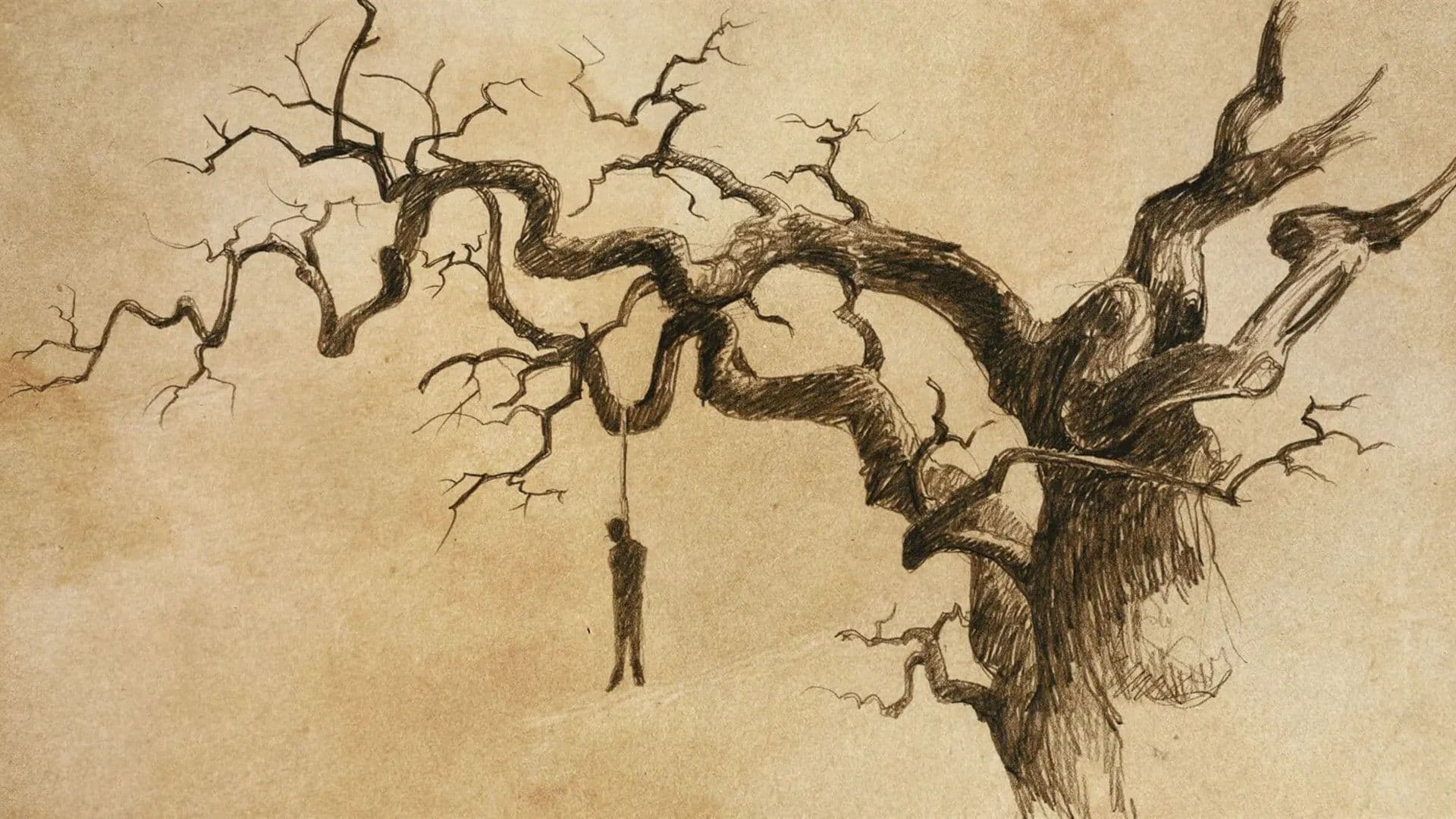

And their leader, Zemnarihah, was taken and hanged upon a tree, yea, even upon the top thereof until he was dead. And when they had hanged him until he was dead they did fell the tree to the earth, and did cry with a loud voice, saying: May the Lord preserve his people in righteousness and in holiness of heart, that they may cause to be felled to the earth all who shall seek to slay them because of power and secret combinations, even as this man hath been felled to the earth. 3 Nephi 4:28-29

The Know

After the combined Nephite and Lamanite forces defeated the armies of the Gadianton robbers, they executed the Gadianton leader Zemnarihah with ceremonial hanging, prayer, and celebration:

And their leader, Zemnarihah, was taken and hanged upon a tree, yea, even upon the top thereof until he was dead. And when they had hanged him until he was dead they did fell the tree to the earth, and did cry with a loud voice, saying: May the Lord preserve his people in righteousness and in holiness of heart, that they may cause to be felled to the earth all who shall seek to slay them because of power and secret combinations, even as this man hath been felled to the earth. (3 Nephi 4:28–29)

A few scholars, including John W. Welch and Daniel L. Belnap, have argued that the hanging of Zemnarihah in the Book of Mormon has roots in the Old Testament law and in Jewish tradition––particularly the idea of hanging as a shameful, cursed mode of punishment for violent criminals and political rebels.1

The Old Testament has many stories in which people are “hung.”2 Examples include the death of the baker who was imprisoned with Joseph, the executions of Amorite kings during Joshua’s conquests, the post-battle display of the bodies of Saul and his sons, the hanging of Haman, and others.3 Many of these seem to refer to the suspension of a body after the death of the individual, though a few have been interpreted to refer to death by hanging.4 As Welch notes, “The purpose of hanging the corpse was to publicly humiliate the offender and deter others from committing similar offenses,” as is often done universally.5 Like the execution of Nehor (which could have been a stoning, hanging, or both), it was a shameful, or “ignominious,” death.6

Moreover, the Old Testament goes beyond seeing the public shame of a hanging: a ritual impurity accompanied it. Deuteronomy prohibits a body to be hung overnight because it was said to ritually defile the land: “And if a man have committed a sin worthy of death, and he be to be put to death, and thou hang him on a tree: his body shall not remain all night upon the tree, but thou shalt in any wise bury him that day; (for he that is hanged is accursed of God;) that thy land be not defiled, which the Lord thy God giveth thee for an inheritance” (Deuteronomy 21:22–23).

Thus, hanging a body was a socially and spiritually derisive way to treat an executed individual. Although it is not totally clear what the qualifications for hanging were or whether individuals became “accursed of God” by their crime or by being hung itself, Belnap notes that cursing often indicated spiritual separation from God: “Cursing included not only death and misfortune but also, more significantly, being cut off and separated and even losing one’s name of place before God. … Thus, hanging was not only an act of humiliation, but an act of excommunication.”7

Belnap further suggests that the ritual curse connected to hanging may stem from being stuck between the heavens and the earth. This language can be found in the Old Testament account of the prince Absalom getting his hair stuck in a tree and hanging “between the heaven and the earth” before being killed by Joab (2 Samuel 18:9).8 The same language is used for Nehor’s shameful execution: “They carried him upon the top of the hill Manti, and there he was caused, or rather did acknowledge, between the heavens and the earth, that what he had taught to the people was contrary to the word of God; and there he suffered an ignominious death” (Alma 1:15; emphasis added). Regarding this language, Belnap noted: “Though this certainly works as a literal description of what happens when one is hung, the space in which he is found––neither on earth nor in heaven––suggests that [he] is suspended in a liminal space, somewhere in between, belonging in neither space … reflecting the cut-off status of the person from the community [and as] an act of excommunication.”9

Welch notes that texts in the Dead Sea Scrolls also recognizes hanging as “the prescribed penalty for one who ‘informs against [or slanders] his people, and delivers his people up to a foreign [pagan] nation,’ or one who ‘has defected into the midst of nations, and has cursed his people, [and] the children of Israel.’”10 The prescription of hanging for political rebels can help explain some of the passages involving hanging in the Old Testament like that of the baker, the Amorite kings, Absalom, and Ahithophel.11

All this also fits precisely with Zemnarihah’s crime. Welch wrote, “As a robber who had defected away from his people, who had been party to threatening demands that the Nephites deliver up their lands and possessions (3 Nephi 3:6), and who had attacked his people, Zemnarihah was a most notorious and despicable traitor. He received nothing short of the most humiliating public hanging.”12

The chopping of the tree upon which Zemnarihah hung further demonstrates the ritually cursed nature of hanging. Belnap notes that the tree may have been cut down with Zemnarihah still on it as a way to show that Zemnarihah was permanently trapped in a state between heaven and earth.13 The felling of the tree also served as a simile curse—a physical representation of what would happen to others who spiritually and politically rebelled: “May the Lord preserve his people in righteousness and in holiness of heart, that they may cause to be felled to the earth all who shall seek to slay them because of power and secret combinations, even as this man hath been felled to the earth.”14

Welch further connects the cutting of the tree to rabbinic customs surrounding hanging: “It is also significant that the tree on which Zemnarihah was hung was chopped down. This appears to have been done consciously in accordance with ancient legal custom. Although the practice cannot be documented as early as the time of Lehi, Jewish practice shortly after the time of Christ expressly required that the tree upon which the culprit was hung had to be buried with the body. Hence the tree had to be chopped down.”15

The Why

Knowing that hanging was understood to be a ritually cursed execution for political rebels situates Zemnarihah’s execution comfortably within ancient Israelite tradition. The presence of a simile curse as well as of non-biblical Jewish traditions in the Zemnarihah narrative bolster the graphic realism of the account.

The continuity of so many details about Israelite hanging and cursing among the Nephites also suggests that they, like Paul, would have understood Jesus’s crucifixion as a form of hanging.16 The ritual cursing that accompanied the suspension of someone, as seen in Zemnarihah’s story, adds additional meaning to the Crucifixion. Jesus thus took upon himself not only all sins but also all cursings, and He did so for our sake in order to deliver the faithful from everything, even the curse of breaking God’s law. Paul taught,

For as many as are of the works of the law are under the curse: for it is written, Cursed is every one that continueth not in all things which are written in the book of the law to do them. But … Christ hath redeemed us from the curse of the law, being made a curse for us: for it is written, Cursed is every one that hangeth on a tree: that the blessing of Abraham might come on the Gentiles through Jesus Christ; that we might receive the promise of the Spirit through faith. (Galatians 3:10–11, 13–14)

Similarly, long before the mortal coming of Christ, Jacob invited readers who look intently upon the ritually shameful death of Jesus by suspension to both acknowledge it and be willing to bear similar shame and metaphorical crosses for Christ’s sake. Being still close to his family’s ancient Israelite roots, Jacob taught that “they who have endured the crosses of the world, and despised the shame of it, they shall inherit the kingdom of God. … Wherefore, we would to God ... that all men would believe in Christ, and view his death, and suffer his cross and bear the shame of the world.”17

John W. Welch, The Legal Cases in the Book of Mormon (Brigham Young University Press; Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2008), 313–322.

Daniel L. Belnap, “‘They Did Fell the Tree’: The Hanging of Zemnarihah as a Ritual Resolution for Nephite Trauma,” in They Shall Grow Together: The Bible in the Book of Mormon, ed. Charles Swift and Nicholas J. Frederick (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Deseret Book, 2022).

John A. Tvedtnes, “More on the Hanging of Zemharihah,” in Pressing Forward with the Book of Mormon: The FARMS Updates of the 1990s, ed. John W. Welch and Melvin J. Thorne (Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies [FARMS], 1999).

John W. Welch, “The Execution of Zemnarihah,” in Reexploring the Book of Mormon: A Decade of New Research, ed. John W. Welch (Deseret Book; FARMS, 1992).

- 1. John W. Welch, The Legal Cases in the Book of Mormon (Brigham Young University Press; Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2008), 313–322, 351–356; Daniel L. Belnap, “‘They Did Fell the Tree’: The Hanging of Zemnarihah as a Ritual Resolution for Nephite Trauma,” in They Shall Grow Together: The Bible in the Book of Mormon, ed. Charles Swift and Nicholas J. Frederick (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Deseret Book, 2022), 143–178.

- 2. Belnap, “‘They Did Fell the Tree,’” 144–152. Several Hebrew words are translated “hang” in the King James Version of the Old Testament. Ludwig Koehler, Walter Baumgartner, and Johann J. Stamm, The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament, ed. Mervyn E. J. Richardson, 2 vols. (Boston, MA: Brill, 2001), s.vv. “תלה,” “תלא,” “יקע,” “תקע,” “חנק.”

- 3. Belnap, “‘They Did Fell the Tree,’” 144–152.

- 4. Welch, Legal Cases in the Book of Mormon, 352: “In Zemnarihah’s case, it is clear that he was not executed by stoning or otherwise before his body was hung on the tree; instead, he was ‘hanged ... until he was dead;’ apparently dying by strangulation or suffocation. This suggests that the Nephites understood Deuteronomy 21:22 to allow execution by hanging—a reading the rabbis also saw as possible. While the rabbis generally viewed hanging only as a means in their day of exposing the dead body after it had been stoned, they were aware of an archaic penalty of ‘hanging until death occurs.’” Hanging and various forms of execution with suspension are also attested in ancient America, though as with some instances in the Old Testament it is unclear whether the hanging occurred before or after death. See Scripture Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Pre-Roman Crucifixion,” Evidence ID# 449 (May 30, 2024); Scripture Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Treatment of Prisoners,” Evidence ID# 220 (July 31, 2021).

- 5. Welch, Legal Cases in the Book of Mormon, 351.

- 6. Welch, Legal Cases in the Book of Mormon, 231–232; Belnap, “‘They Did Fell the Tree,’” 157; Scripture Central, “Why Did Nehor Suffer an ‘Ignominious’ Death? (Alma 1:15),” KnoWhy 108 (May 26, 2016).

- 7. Belnap, “‘They Did Fell the Tree,’” 155; see also pages 147, 153–156. The phrase in Deuteronomy 21:23 literally reads, “For the one being hanged is a curse [of/from] God.” Because hanging could be reserved both for those who are already cursed from God and for those who are made an affront to God through hanging, the ambiguity has remained. Belnap (page 154) wrote, “In any case the hanged person is understood as cursed.”

- 8. Belnap, “‘They Did Fell the Tree,’” 148

- 9. Belnap, “‘They Did Fell the Tree,’” 148, 155.

- 10. Welch, Legal Cases in the Book of Mormon, 352–353.

- 11. Belnap, “‘They Did Fell the Tree,’” 155–156.

- 12. Welch, Legal Cases in the Book of Mormon, 353.

- 13. Belnap, “‘They Did Fell the Tree,’” 158: “If the corpse remained on the tree, as indicated above, then it is possible that the act symbolically rendered Zemnarihah in a permanent cursed state of separation.”

- 14. 3 Nephi 4:29, emphasis added; Belnap, “‘They Did Fell the Tree,’” 156–161; Welch, Legal Cases in the Book of Mormon, 342, 355; Scripture Central, “Why Did the People Cut down the Tree After Hanging Zemnarihah? (3 Nephi 4:28),” KnoWhy 192 (September 21, 2016).

- 15. Welch, Legal Cases in the Book of Mormon, 354; see also page 155.

- 16. Scripture Central, “Pre-Roman Crucifixion.”

- 17. 2 Nephi 9:18; Jacob 1:8. For more about Jacob’s association with shame and the cross, see Scripture Central, “Why Is Jacob’s Distinctive Voice Significant? (Jacob 1:17),” KnoWhy 725 (April 2, 2024); John Hilton III, Voices in the Book of Mormon: Discovering Distinctive Witnesses of Jesus Christ (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2024), 35–36.