Magazine

Pitfalls Avoided by the Translator of the Book of Mormon

Title

Pitfalls Avoided by the Translator of the Book of Mormon

Magazine

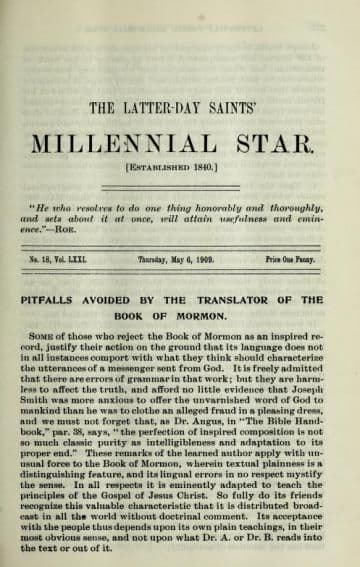

The Latter Day Saints' Millennial Star

Publication Type

Magazine Article

Year of Publication

1909

Authors

Brookbank, Thomas W. (Primary)

Pagination

273–279

Date Published

6 May 1909

Volume

71

Issue Number

18

Abstract

This two-part series describes many mistakes that Joseph Smith could have made if he were a fraud who wrote the Book of Mormon. For instance, Joseph Smith did not incorporate modern geographical names, punctuation, chapter and verse markings, modern terms for clothing, alcoholic beverages, military terms, days of the week, names of months, nor titles such as mister or doctor. The first part begins the series.

PITFALLS AVOIDED BY THE TRANSLATOR OF THE BOOK OF MORMON.

Some of those who reject the Book of Mormon as an inspired record, justify their action on the ground that its language does not in all instances comport with what they think should characterize the utterances of a messenger sent from God. It is freely admitted that there are errors of grammar in that work; but they are harmless to affect the truth, and afford no little evidence that Joseph Smith was more anxious to offer the unvarnished word of God to mankind than he was to clothe an alleged fraud in a pleasing dress, and we must not forget that, as Dr. Angus, in “The Bible Handbook,” par. 38, says, “the perfection of inspired composition is not so much classic purity as intelligibleness and adaptation to its proper end.” These remarks of the learned author apply with unusual force to the Book of Mormon, wherein textual plainness is a distinguishing feature, and its lingual errors in no respect mystify the sense. In all respects it is eminently adapted to teach the principles of the Gospel of Jesus Christ. So fully do its friends recognize this valuable characteristic that it is distributed broadcast in all the world without doctrinal comment. Its acceptance with the people thus depends upon its own plain teachings, in their most obvious sense, and not upon what Dr. A. or Dr. B. reads into the text or out of it.

Joseph Smith is freely charged by his opponents with every one of the lingual but unimportant errors appearing in his work of translation; but when we consider how his pathway was everywhere strewn with hidden pitfalls and deadly traps, it is simply a miracle that he did not make some mistake that no effort of his friends could conceal or explain away, and that might have vitiated his work from beginning to end. On every page of the Book of Mormon there was opportunity for the fall of an impostor had Joseph Smith been of that class; yet he was preserved from the lurking snares that surrounded him, and only the power of God was equal to the task of his deliverance. Specifying now particular instances in which the Divine guidance and protection are noticeable, we find:—

That the Book of Mormon makes no use of geographical names which belong exclusively to a later date than B.C. 600, excepting, of course, those that are of Nephite origin. In the time of Homer, or about B.C. 900, the world was regarded as a sort of circular plane, of which Greece appears to have been the centre. A line drawn from that country to the eastern boundaries of the Black Sea will give the half diameter of this earth-plane, and by drawing a circle round Greece, on the basis of the semi-diameter just given, one will get a fairly accurate outline of the geography of those early times. Hecatanis, about B.C. 550, gives us an enlarged view of the world, expanding its known limits considerably, but principally eastward and southward, eastward so as to include Media, and southward to the mouth of the Red Sea.

It was not until the days of Eratosthenes, B.C. 276 to B.C. 196, that geography was reduced to a regular system, and its foundation laid on clear and solid principles. It can not be denied, how ever, that adventurers occasionally passed beyond the limits of the world as mapped out in the Homeric period, and in the time of Hecateeus; but no permanent enlargement of geographical knowledge resulted from such expeditions; just as later the world’s boundaries were not laid beyond the Atlantic by geographers, when the Norsemen discovered America, long before Columbus obtained his first glimpse of its shores. It is very evident, therefore, that Nephi’s knowledge of the geography of the Old World was limited to the area already pointed out, and none of the other Book of Mormon writers could have been any better informed, and all of them were wholly in darkness respecting the existence of the New World until they set foot upon it. A few’ names of ancient application that are familiar to us, were also well known to them; among which may be mentioned Egypt, Babylon, and Red Sea,—the latter a mere translation from original terms meaning “red” and “sea.” These, and others that might be mentioned are all Biblical names, and were used in the Scriptures long before B.C. 600, and, therefore, their occurrence in the Book of Mormon has the sanction of antiquity.

Now, the book just named speaks of three different colonizing movements, all of them having the land now called America for their objective. One of these colonies set out from Babylon, the other two from Jerusalem. Nephi gives us far greater details of that one to which he belonged than we find anywhere of the others. Beginning with the starting point—Jerusalem—he tells us what direction his people took, and finally brings them down to the shores of the Red Sea, and having launched them, with himself, upon its waters in a ship specially built for the voyage to the “land of promise,” he immediately ceases all mention of further geographical details. Such a course does not accord very well with certain features of the first part of his narrative, but he could not do otherwise than he did, for just there he was at the limit of the geography of his day, and a single further step forward in this connection would have involved the Book of Mormon in an inexplicable blunder. The Indian and the Pacific Oceans were not down on any map that Nephi possessed. What restrained him from naming the waters on which the colony voyaged after passing out of the Red Sea? How does it transpire that he does not even say that they then came to the great “Ocean”? That would be only one little word and apparently nothing serious could result from its use by Nephi; yet that single term, if used, would be almost as fatal to his claim of being au historical character as though he had said that after leaving the Red Sea they crossed the Indian Ocean, then passed into the quiet Pacific and finally came to America; for that word “ocean” is derived from a Latin term, and at the time when Nephi left Jerusalem, B.C. 600, the Latins were not of sufficient importance to give names to far-distant divisions of either land or water; and especially to those that were unknown to European geographers, and not down on the maps.

Respecting the colony that set out from Babylon, we are informed that it first went northward, and later crossed “many waters” in barges that were built for that purpose. These “many waters” were the inland seas of Asia. In this instance, the thoughtless naming of all, or of any of these bodies of water with either ancient or modern names would have been an irretrievable error, for when the colony of Jared crossed them about B.C. 2200, they had no names, and doubtless for centuries thereafter they were unnamed by man. As it is not the Nephites, but the Jaredite historians who give the original account of the Jaredite people, the Book of Mormon records would be in a sad tangle if they made it appear that those far inland seas were named at a time when the population of the whole world was concentrated around the tower of Babel.

Again, the Book of Mormon speaks in a number of places of the “narrow neck of laud” which is known to us as the Isthmus of Panama. In this neighborhood, and in the Andean countries of Bolivia, Peru, Equador and Colombia, the scene of the greater portion of the Nephites is laid. Its writers speak of rivers and mountains there, and of large bodies of water northward—presumably the great lakes of North America—but never is there a slip made in identifying any of them by the use of modern names; nor is any point or place located by the familiar principles of latitude and longitude. The writers of the Book of Mormon do not refer to the later rulers of their people as Incas, nor do they appeal to the existence of ruins remaining in their land in order to verify their story. References far less openly modern in origin than those just given would be fatal to their claims as writers of authentic history.

The life of the Book of Mormon is thus seen to hang suspended, as it were, upon the use of a compromising word, a single reference with a distinct modern coloring only, or we might say, the careless slip of a pen. But blunders of this character (so easily made in a spurious work simulating the character of the Book of Mormon) are not found in it. Multitudes of instances of the kind just noticed, and every one of them affording an opportunity for disgrace and ruin, swarm about the pathway of any man, unlearned or learned, who dares attempt the task of writing by his own power the history of an ancient people without having a scrap of their authentic history for a guide.

Let us now imagine Joseph Smith, a young man, unlearned, unschooled, wholly untrained for writing a book of any kind, not to mention the unusual difficulties and dangers connected with a work like the Book of Mormon, attempting to compose the latter as a religious romance, or a purposed fraud. His knowledge of all ancient matters amounts practically to nothing. (How defiant it was for him to choose the field of which he knew the least for his operations!) There are limits, or boundaries between the ancient and the modern which he cannot pass, and still retain for a moment the confidence of his fellow-men as an inspired translator of ancient records. We see him reach the line between safety on the one side and discredit and disgrace on the other. This line of separation is sometimes almost invisible, and as he reaches it the impetus of his progress seems sufficient to bear him onward to ruin as a word or two will do the work; but he pauses at the proper point, always pauses there, and some people try to explain his course, or account for his preservation, on one contradictory theory or another, ever failing to perceive that if Joseph Smith were such a man as his opponents claim, he would doubtless have plunged headlong into the first one of these pitfalls that lay hidden from him but so directly in his way.

Joseph Smith avoided another blunder of a serious nature when he refrained from dividing the text of the Book of Mormon into chapters and verses. The title page of later editions shows that Orson Pratt, Sen., is the author of those divisions; and it was he also who added the references, etc. These divisions, therefore, formed no part of the original text, and that fact is a solid truth in the Mormon foundation. The practice of thus dividing the scriptures is of comparatively recent date, and the ancient Jews knew nothing of such work. The first book that ever appeared in printed form was a copy of the Vulgate—a Latin version of the scriptures by Jerome, who was engaged on the work of translation from 382 A.D. to 405 A.D. This version was the first publication that was ever divided into chapters and verses as our Bibles now are; but this work was not performed until 1227 A.D., when Cardinal Hugo undertook it. The Massoretic versification of the scriptures was in use before this time; but that was an arbitrary arrangement of the text by which it could be recited melodiously; and was in no way similar to our present Biblical division into chapters and verses. Such, in brief, is the history of the early work of dividing the contents of books, and especially the scriptures, into convenient parts, and none of it, as practised at present, antedates the thirteenth century. Since the early Palestinian Jews knew nothing of this divisional system, it is plain that Nephi and his fellow-writers were no wiser. We thus see that if the Book of Mormon had come from the hands of Joseph Smith separated into chapters and verses as original work of antiquity, he would have been open to the charge of fraud. When engaged in his work he had before him, in the Bible, a whole volume of the word of God separated divisionally in every part as we now find it, and it may be assumed, very properly, that, for anything he knew to the contrary, these divisions were of ancient date, if they did not form part of the original writings. How many of the “young, unlearned” men of his day, brought up as he was, knew anything whatever concerning this matter? What power or influence restrained him from making a fatal mistake at this point? When did Joseph Smith study ancient history to such an extent that he is so often—always, we should say—found in harmony with it, and with the developments of human knowledge?

Closely related to the possible blunder just noticed which Joseph Smith did not make, is another that an impostor almost certainly would have made somewhere in his work. In the Book of Mormon there are many quotations from the ancient Jewish scriptures, comprising about a score of whole chapters, besides numerous others of less extent, and indirect references may be found on many pages; but in no instance is the chapter or verse where they are originally recorded given. Quotations from the writings of the early prophets and other writers of scripture are made in the Book of Mormon no more definitely as to the particular section where quoted from than was done by Christ and His apostles.

Joseph Smith avoided making a fatal blunder when he prepared the manuscript of his translation and delivered it to the printer without a mark of punctuation in it. It seems almost beyond belief that such was the case; but we have the statement of the printer (Mr. Gilbert) of the first edition of the Book of Mormon to that effect. In response to an inquiry by two gentlemen named Kelly, residents of Michigan, who personally visited him for the purpose of investigating some phases of the “Mormon” question, Mr. Gilbert said: “I * * * have seen Joseph Smith a few times; but (was) not acquainted with him. Saw Hyrum (Smith) quite often. I am the party that set the type from the original manuscript for the Book Mormon. I would know the manuscript to-day if I should see it. The most of it was in Oliver Cowdery’s handwriting, some in Joseph’s wife’s, a small part though. Hyrum Smith always brought the manuscript to the office; he would have it under his coat, and all buttoned up as carefully as though it were so much gold. He said at the time that it was translated from plates by the power of God, and they were very particular about it. We had a great deal of trouble with it. It was not punctuated at all. They did not know anything about punctation, and we had to do that ourselves.”

Mr. Gilbert in his statement that the manuscript of the Book of Mormon was not punctuated because “they”—Joseph and Hyrum Smith and Oliver Cowdery—“knew nothing about punctuation,” does not give the real reason why the papers were handed to him by Hyrum Smith in that condition. If Joseph Smith and his brother knew nothing about punctuation, no one can consistently claim that Oliver Cowdery, who was a school teacher, was no better informed; and ordinary regard for his own reputation would never have allowed him to pass a manuscript of his own writing to a public printer without some attempt being made to put in place some of the most common marks of punctuation at least. There can be no doubt that he would have done this work, if Joseph Smith had authorized or permitted it. Mr. Gilbert’s testimony discloses to us the intense feelings of sacredness with which Joseph Smith and his immediate associates regarded the work in which they were engaged. The manuscript of the translation from the original plates of the Book of Mormon was as precious in their sight as gold was in Mr. Gilbert’s eyes—as precious as he thought that coveted metal would be in the sight of men who seldom saw its color, and who badly needed it.

Now, there was nothing of our present system of punctuation found anywhere in the original Nephite writings, and not one jot or tittle would their translator add in any respect without the authority of the Holy Spirit. Our modern system of punctuation was wholly unknown to the Nephites. In the Bible Dictionary accompanying the American Revised Bible, Standard Edition, Thomas Nelson and Sons, New York, Article, Writing (Hebrew), we find the following statement: “There was no system of punctuation, nor clear spacing between words.” Dr. Angus, in the Bible-Handbook, page 37, says: “In the ninth century the note of interrogation and the comma were introduced; and on the same page he further says that a manuscript systematically punctuated is not earlier than the eighth century. It is generally supposed that our present system of punctuation grew out of the work of the Massoretes, whose finished labor can not be placed earlier than the seventh century. It is thus clearly seen that it was impossible for the Book of Mormon authors to apply modern punctuation in their writings, and especially when recorded in hieroglyphics. The consistency observable in Joseph Smith’s work when he prepared the manuscript of his translation without separating points, is beautiful and significant, and Mr. Gilbert's statement does not reflect upon the intelligence of Joseph and Hyrum Smith or Oliver Cowdery; but it is invaluable as showing how profoundly sacred all these men regarded the work that they were called upon to perform. The writer is free to confess that among all the rational evidences which make up the demonstration of good faith on the part of Joseph Smith and his co-laborers in the work of translation, there is not one that impressed him more deeply than that unpunctuated manuscript. Men who did not dare add even a comma to what they regarded as sacred, were far too honest to practice deception upon their fellow-men, and we are grateful that none of them vitiated their great work by glossing it over with modern devices. The Book of Mormon records were very properly brought forth in the translation as the Nephite writers closed them; but when at last they became public property through the press, modern divisional arrangements were introduced to meet modern requirements—to facilitate the reading of the records by people of our times.

Thomas W. Brookbank.

(To be continued.)

Subject Keywords

Bibliographic Citation

Terms of use

Items in the BMC Archive are made publicly available for non-commercial, private use. Inclusion within the BMC Archive does not imply endorsement. Items do not represent the official views of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or of Book of Mormon Central.