Magazine

Parentage of Ancient American Art and Religion (3 November 1910)

Title

Parentage of Ancient American Art and Religion (3 November 1910)

Magazine

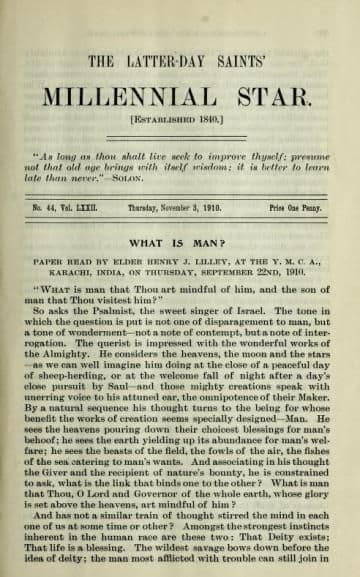

The Latter Day Saints' Millennial Star

Publication Type

Magazine Article

Year of Publication

1910

Authors

Brookbank, Thomas W. (Primary)

Pagination

692–695

Date Published

3 November 1910

Volume

72

Issue Number

44

Abstract

This series discusses the Babylonian and Israelite people who established Book of Mormon civilizations. Brookbank suggests that the Jaredites were Semites. The ancient ruins left in America have distinct Babylonian and Assyrian influence. The Nephite-Israelite people of the Book of Mormon have also left their mark upon civilization. The sixth part covers low relief sculptures, sub-river tunnels, large walls, aqueducts, and mechanical appliances.

PARENTAGE OF ANCIENT AMERICAN ART AND RELIGION.

(Continued from page 686.)

Your attention is now particularly requested to the fact that this design gave to the Babylonians a “holy house in a high place.” It should not be forgotten, since later much will be said about the Israelitish holy “houses in high places.” It is evident from the descriptions of these Babylonian temples that whatever ceremonies were conducted in the “cell” or “chapel” at the summit of the pyramid, the mass of worshippers could not witness them. The Babylonians were a highly religious people in their way, and so the grounds round about the temples were also devoted to religious purposes. This arrangement gave room for the accommodation of the masses who attended the public ceremonials at the temples, and paid their devotions to the gods. The terraces in the temple foundations, arranged like tiers of seats, could afford the nobility and the priestly officials admirable view-points, and places for couches, where the occupants might recline at their ease during the services. But we yet lack some recognized authority for the statement that the grounds around the temples were consecrated to religious purposes, and we turn to the American Encyclopedia Britannica for it, which, describing the temple of Bel at Babylon, says that on the topmost platform was a shrine, and at the base of the whole structure there was another shrine, with a table and two images of solid gold. The account continues, “Two altars were placed outside the chapel, the smaller one being of the same metal as the images within the lower shrine, or gold. From what has now been remarked respecting these matters, the following points are clear:

(1.) Temples in Babylonia were pyramidal in form.

(2.) At the summit of the pyramid was a shrine, or chapel.

(3.) The sides of the pyramid were constructed in series of steps or platforms.

(4.) Altars were erected at the base of the temple proper.

(5.) Images were placed before the altars.

Can we now find the counterpart of all this in America? The answer is of great worth to our case, if an affirmative answer can be truthfully returned, and this is precisely what the ancient ruins in this land warrant in every particular.

A single quotation from the authority last named ought to set at rest all questions relating to the identity in design between the Babylonian temples and the Teocallis, or temples, of the ancient Americans. It says of later Mexican structures that they “were pyramids composed of terraces placed one above another, like the temple of Belas at Babylon. * * * One or two small chapels stood upon the summit enclosing images of the deity.” (There was also a golden image in the topmost chapel of the temple of Bel.)

Stephens and other explorers among the American ruins confirm this statement of the American Encyclopedia Britannica, by their descriptions of these Teocallis, as they are called, pyramidal buildings with shrines, chapels, or temple “cells,” are of frequent occurrence, and, as Mr. Stephens says, there is not a pyramid in America, (so far of course as he was aware), which had not a building, or the remains of one on its summit; and the steps or terraces in the sides of the foundations on which the shrines or other buildings rest, are frequently mentioned by him in his works.

Now, it is manifest that there is a period of time extending from the era when Copan and Palenque were built in ancient America, down to the more recent Mexican era, and which covers a thousand years, or more likely two thousand, during which the Babylonian plan of building pyramidal temples was followed in this country in early days. The ineffaceable hold which this design had upon the minds of the people of the Euphrates districts and the ancient Americans alike, is evidence such as can seldom be produced to establish racial affinity. But the case is not yet concluded.

We have found that at or near the base of the great temple in Chaldea, were placed images and alters. Turning to Mr. Stephen’s plan of Copan, Travels in Central America, etc., Vol. I, facing page 133, we find all along the south side of the temple enclosure, remains of pyramidal buildings. The “idols” and altars marked C, D and E, on the plan, are near the base of the temple walls. From round and about the position of the altar and “idols” marked A and B pyramidal temple bases rise on almost all sides. Among the group of altars and “idols” at the right in the plan, the two pointed out as S and T stand close together, with the accompanying altar in front. It is especially observed by Mr. Stephens that the one marked T stands at the foot of a “wall of steps.” Other remains of walls apparently identical in structure partly enclose most of the “idols” in this southern cluster, and from the circumstance of the encircling wall being certainly terraced in places, there can be little doubt but all the idols at that particular point were erected also near the bases of pyramidal temples—time and the ravages of the elements having reduced them to fragments of walls of steps. But be the fact as it may in these instances, the relative position of the other “idols” and associated altars near the temple bases, completes the Babylonian plan for temple structures and consecrated grounds around them with all the essentials for idolatrous worship and ceremonials. Who can successfully maintain that this combination of remarkable and similar features manifested together in one matter, like that other example embracing harem concerns, is due to chance?

24. Low Relief Sculpture.

The best works of the Assyrian sculptors, are found among their low-reliefs. Professor Rawlinson speaking on this point says that “The low-relief was to the Assyrian the practical mode in which artistic power found vent among them. They used it for almost every purpose to which mimetic art is applicable : to express their religious feelings and ideas ; to glorify their kings; to hand down to posterity the nation’s history and its deeds of prowess,” etc., etc. The professor concludes his remarks of a similar kind with the statement that “It is not too much to say that we know the Assyrians, not merely artistically, but historically and ethnologically, chiefly through their bas-reliefs, which seem to represent to us the entire life of the people.”

A quotation from an article by Mr. Charles Hallock, M. A., entitled The Primeval North American, and which appeared in Harper s Magazine for August, 1902, sets forth in a plain and concise manner about all that need be said respecting this same artistic feature among the ancient Americans. He states that “Memorabilia of permanent occupancy in bas-relief sculpture, and hieroglyphics occur everywhere among the ruins of the exhumed cities of Yucatan, and are repeated all over Central America and parts of South America.”

Describing the ruins of the great city of Palenque, Stephens makes no mention of any sculpture not of the low-relief order, examples of which are numerous at that city, and other visitors to the remains there, and to other cities elsewhere, frequently mention this characteristic of the ancient work, and so it appears that we may without claiming too much, say, paraphrasing the language of Professor Rawlinson, that the ancient Americans may be known ethnologically as being related to the Assyrians and the Babylonians by the multitudinous examples of their low-relief sculpture.

25. Hieroglyphical Identities, and Like Customs.

A reference to the hieroglyphical system of writing that obtained among the aborigines of this country having just been made, what is to be said respecting this matter will be concluded now.

Quoting Mr. Hallock again we find that the hieroglyphics include the outlines of animals, clan marks, totems, secret-society insignia, challenges, defiances, taunts, since practised by all Indian tribes, cautions against ambuscades and natural obstacles, directions to water holes, camping grounds, and rendezvous, as well as mention of skirmishes, forced marches, misadventures, and special events—practices which were in vogue in Palestine and Egypt in Biblical times. Every new archaeological discovery adds testimony to establish the more than hypothetical origin of our American aborigines, and the close relationship between their ancestors of Central America and the peoples of Egypt and Asia.

The Bureau of Ethnography at Washington has remarked the identity of certain hieroglyphics in form and significance with those of Egypt and the East.

When such remarkable facts as these are being developed by scientific men, who have no affiliation with the “Mormons,” it seems impossible that the time can be much longer prolonged until such a flood of light will be thrown upon certain ethnological questions that are closely associated with others of a religious nature, and which now occupy much of the world’s attention, that he who will not see and acknowledge the truth in the matter, is wilfully blind, and stiff-necked almost beyond the hope of relief.

There are quite a number of other corresponding art features that are deserving of extended consideration; because each and every one of them is competent to a greater or less extent to assist in establishing the proposition that the source of ancient American art, science and civilization is found in Babylonia; but for the present a brief notice of a few of them must suffice, and those selected are as follows:—

27. Tunnels Under Rivers.

A tunnel was constructed under the Euphrates, connecting the two sections of the City of Babylon which were built on opposite banks of the river. At a place near Chavin De Huanta in Peru, a river there is said to have been tunneled.

28. Walls of Great Thickness and Height.

In both countries concerned, immense walls for various purposes were constructed.

29. Great Aqueducts and Canals.

Babylonia was traversed by great canals which could dry the Euphrates. The ancient Americans built great aqueducts hundreds of miles long—facing them sometimes with hewn stone, and cutting them through mountain ranges.

30. Mechanical Appliances of Immense Power.

The immense stones moved and put in place by the aboriginal inhabitants of America, is evidence that they had machines of equal power with any that could be found in Babylonia.

(To be continued.)

Subject Keywords

Bibliographic Citation

Terms of use

Items in the BMC Archive are made publicly available for non-commercial, private use. Inclusion within the BMC Archive does not imply endorsement. Items do not represent the official views of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or of Book of Mormon Central.