Magazine

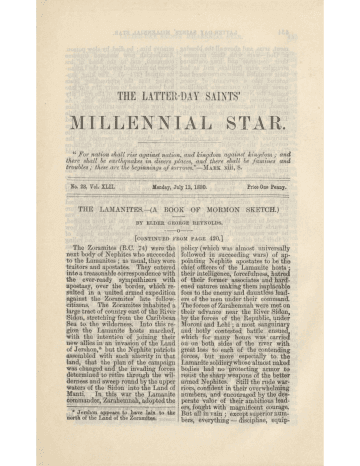

The Lamanites (A Book of Mormon Sketch) (12 July 1880)

Title

The Lamanites (A Book of Mormon Sketch) (12 July 1880)

Magazine

The Latter Day Saints' Millennial Star

Publication Type

Magazine Article

Year of Publication

1880

Authors

Reynolds, George (Primary)

Pagination

433–436

Date Published

12 July 1880

Volume

42

Issue Number

28

Abstract

This series sketches out the character of the Lamanites. Reynolds also writes concerning Sariah, Lehi’s wife. The fourth part covers the defection of the Zoramites to the Lamanites and the subsequent wars with the Nephites.

THE LAMANITES.—(A BOOK OF MORMON SKETCH.)

BY ELDER GEORGE REYNOLDS.

[Continued from page 420.]

The Zoramites (B.C. 74) were the next body of Nephites who succeeded to the Lamanites; as usual, they were traitors and apostates. They entered into a treasonable correspondence with the ever-ready sympathizers with apostasy, over the border, which resulted in a united armed expedition against the Zoramites’ late fellowcitizens. The Zoramites inhabited a large tract of country east of the River Sidon, stretching from the Caribbean Sea to the wilderness. Into this region the Lamanite hosts marched, with the intention of joining their new allies in an invasion of the Land of Jershon,1 but the Nephite patriots assembled with such alacrity in that land, that the plan of the campaign was changed and the invading forces determined to retire through the wilderness and sweep round by the upper waters of the Sidon into the Land of Manti. In this war the Lamanite commander, Zarahemnah, adopted the policy (which was almost universally followed in succeeding wars) of appointing Nephite apostates to be the chief officers of the Lamanite hosts; their intelligence, forcefulness, hatred of their former associates and hardened natures making them implacable foes to the enemy and dauntless leaders of the men under their command. The forces of Zarahemnah were met on their advance near the River Sidon, by the forces of the Republic, under Moroni and Lehi; a most sanguinary and hotly contested battle ensued, which for many hours was carried on on both sides of the river with great loss to each of the contending forces, but more especially to the Lamanite soldiery whose almost naked bodies had no protecting armor to resist the sharp weapons of the better armed Nephites. Still the rude warriors, confident in their overwhelming numbers, and encouraged by the desperate valor of their ambitious leaders, fought with magnificent courage. But all in vain; except superior numbers, everything—discipline, equipment, arms, and above all the blessing of God—were with their enemies: their desperate and long-continued struggles were fruitless, and at last their wounded leader surrendered and entered into a covenant of peace, never again to commence hostilities against the Nephites. Having given this promise, and after being disarmed, the magnanimous Moroni permitted the survivors to return to the Land of Nephi.

Peace, however, was but short lived; internal dissensions created by the intrigues of apostates and royalists convulsed the Nephite community. The rebels were led by a descendant of Zoram, the servant of Laban, named Amelekiah. Being overwhelmingly defeated by Moroni he fled to the Lamanites, and there evolved a plot worthy of a demon, which only ceased with life. He was a Napoleon in ambition and diplomacy, and possibly also in military skill. On the first favorable opportunity after reaching the Lamanite Court, he commenced to rekindle the fires of hatred towards his former friends. At first he was unsuccessful, the recollection of their late defeats was too fresh in the memory of the multitude. The king issued a war proclamation. It was disregarded. Much as his subjects feared the imperial power, they dreaded renewed war more. Many assembled to resist the royal mandate. The king, unused to such objections, raised an army to quell the advocates of peace, and placed it under the command of the now zealous Amaleckiah. The peace-men had chosen an officer named Lehonti for their king and leader, and he had assembled his followers at a mountain called Antipas. Thither Ameleckiah marched, but with no intention of provoking a conflict; he was working for the good feelings of the entire Lamanite people. On his arrival he entered into a sacred correspondence with Lehonti, in which he stipulated to surrender his forces on condition that he should be appointed second in command of the united armies. The plan succeeded, Amaleckiah surrendered to Lehonti and assumed the second position. Lehonti now stood in the way of his ambition; it was but a little thing to remove him; he died by slow poison. Amaleckiah now assumed supreme command, and at the head of his forces he marched towards the Lamanite capital (374—5). The king, supposing that the approaching hosts had been raised to carry the war into Zarahemla, came out of the royal city to greet and congratulate him. As he drew near he was traitorously slain by some of the creatures of the subtle general, who at the same time raised the hue-and-cry that the king’s own servants were the authors of the vile deed. Amaleckiah assumed all the airs of grief, affection and righteous indignation that he thought would best suit his purpose, then made apparently desperate, but purposely ineffectual efforts to capture those who were charged with the crime, and so adroitly did he carry out his schemes, that before long he wheedled himself into the affections of the queen. They were married, and he was recognized by the Lamanites as their future king.2 Thus far his ambition was realized, but it was far from satisfied, ambition seldom is. Amaleckiah now cherished the stupendous design of subjugating the Nephites and ruling singly and alone from ocean to ocean (B.C. 73). To accomplish this iniquitous purpose, he despatched emissaries in all directions, whose mission was to make inflammatory harangues to the populace, and stir up their angry passions against the Nephites. When this object was sufficiently accomplished, and the deluded people had become clamorous for war, he raised an immense army, armed and equipped with an excellence never before known amongst the Lamanites. This force he placed under the command of Zoramite officers, and ordered its advance into the western possessions of the Nephites.

The Nephites, during this time, had been watching Amaleckiah’s movements and energetically preparing for war. When the Lamanites reached Ammonihah they found it too strongly fortified to be taken by assault, they therefore retired to Noah, originally a very weak place, but now, through Moroni’s foresight and energy, yet stronger than Ammonihah. The Zoramite officers well knew that to return home without having attempted something would be most disastrous, they therefore, though with little hope, made an assault upon Noah, which resulted in throwing away a thousand lives outside its walls, whilst the well-protected defenders had simply fifty men wounded. After this disastrous attempt the Lamanites marched home. Great was the anger of Amaleckiah at the miscarriage of his schemes; he cursed God and swore he would yet drink the blood of Moroni.

During the next year the Lamanits were driven out of the great eastern wilderness which was occupied by numerous Nephite colonies, who laid the foundations of several new cities along the Atlantic coast. Moroni also established a line of fortifications along the Nephites’ southern border, which stretched from one side of the continent to the other.

It was not until the year B.C. 67, that Amaleckiah again succeeded in raising forces to invade Zarahemla. That time seemed most propitious for the success of his ambitious projects, as the Nephites were rent into factions and convulsed with the contentions of republicans and royalists, the latter being in traitorous correspondence with the Lamanite monarch. In this invasion the blood-thirsty king trusted no subordinate officers to lead his vast hosts, but commanded in person. He adopted a different policy to that which had marked former campaigns. He first invaded the extreme southeast of the Nephite possessions and attacked Moroni, the outlying city on the Atlantic seaboard. This he captured. Leaving a small garrison therein, he advanced northward along the sea shore, reducing one after another the fortified cities of Nephihah, Lehi, Morianton, Omner, Gid, Mulek and others of lesser note. Each city as he conquered it was yet more strongly fortified, and a small force left within its walls, whilst he, at the head of the great bulk of his forces, continued his pursuit of the retreating Nephites. This advance was continued until he reached the borders of Bountiful, the most northerly of the lands of the Nephites on the southern continent. Here he was arrested in his triumphal march by a Nephite army under Teancum, and after a day’s hard fighting (the last day of the Nephite year) he camped on the sea shore. During the night the valiant Teancum entered the Lamanite camp, sought out the royal tent, thrust a javelin into the heart of the king as he slept, and then escaped. The next morning the Lamanites, discovering that their leader was slain, retreated to the City of Mulek. Ammaron, the brother of Amaleckiah, succeeded him upon the throne. He continued the war policy, and took personal command of his armies in the south-west. Here also the Nephites had lost ground. The cities of Cumeni, Zeezrom and Antiparah, and to the eastward the Land and City of Manti, were held by the dark and savage warriors from the south. Year after year the war rolled on with heart-sickening loss to both sides, but with gradual relief to the patriot Nephites. Ammaron appears to have possessed all his brother’s hatred and vindictiveness, but not his consummate cunning and great executive ability. The first great disaster his armies suffered was the re-capture of Mulek, outside of which city Jacob (a Zoramite), the commander in that department, was slain. He was a man after Amaleckiah’s own heart—dauntless in battle, unflinching in danger, overflowing in hatred to the enemy, and full of a vicious enthusiasm with which he infused the soldiers under his command. His death was a great blow to the Lamanite cause, and from that time (B.C. 64) the Nephites rapidly, though not uninterruptedly, advanced to victory, and during yet four other years of bloodshed and destruction had to continue the warfare, before they succeeded in wresting every city from the grasp of the invader on both sides of the continent. When the Lamanites were driven to their last hold on Nephite soil—the City of Moroni—the impetuous Teancum determined to again venture into the enemy’s camp and slay King Ammaron, as he had before done his predecessor and brother. Again he succeeded, but at the cost of his own life. The death struggles of the king apprised the guards of the situation, and Teancum was pursued and slain.

And it came to pass in the year B.C. 60, that there were none of the Lamanites remaining to pollute the soil of the Nephites, and peace was restored to the exhausted nations, both of whom had spent their best energies and expended rivers of blood in the terrible struggle brought on to satisfy the hate and ambition of one traitor and murderer. The next king of the Lamanites of whom we read, was Tubal-oath, the son of Ammaron.

[To be continued.]

Subject Keywords

Bibliographic Citation

Terms of use

Items in the BMC Archive are made publicly available for non-commercial, private use. Inclusion within the BMC Archive does not imply endorsement. Items do not represent the official views of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or of Book of Mormon Central.