Magazine

Book of Mormon Names

Title

Book of Mormon Names

Magazine

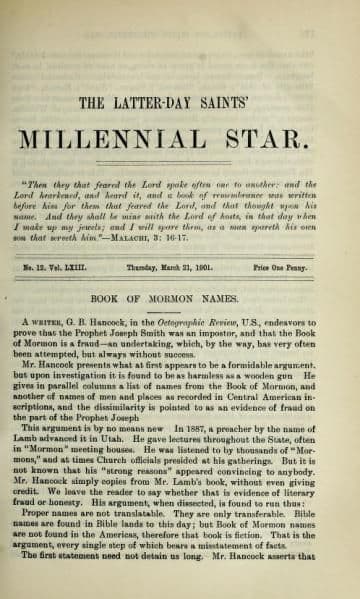

The Latter Day Saints' Millennial Star

Publication Type

Magazine Article

Year of Publication

1901

Editors

Lyman, Francis M. (Secondary)

Pagination

177–180

Date Published

21 March 1901

Volume

63

Issue Number

12

Abstract

This article refutes a polemical claim that Book of Mormon proper names are not translatable, only transferable from one language to another. The fact that no Book of Mormon names appear in Central America does not prove the Book of Mormon to be false. The author cites Book of Mormon names that have Hebrew origins and shows Mayan similarities to Book of Mormon names.

BOOK OF MORMON NAMES.

A writer, G.B. Hancock, in the Octographic Review, U.S., endeavors to prove that the Prophet Joseph Smith was an impostor, and that the Book of Mormon is a fraud—an undertaking, which, by the way, has very often been attempted, but always without success.

Mr. Hancock presents what at first appears to be a formidable argument, but upon investigation it is found to be as harmless as a wooden gun He gives in parallel columns a list of names from the Book of Mormon, and another of names of men and places as recorded in Central American inscriptions, and the dissimilarity is pointed to as an evidence of fraud on the part of the Prophet Joseph

This argument is by no means new. In 1887, a preacher by the name of Lamb advanced it in Utah. He gave lectures throughout the State, often in “Mormon” meeting houses. He was listened to by thousands of “Mormons,” and at times Church officials presided at his gatherings. But it is not known that his “strong reasons” appeared convincing to anybody. Mr. Hancock simply copies from Mr. Lamb’s book, without even giving credit. We leave the reader to say whether that is evidence of literary fraud or honesty. His argument, when dissected, is found to run thus:

Proper names are not translatable. They are only transferable. Bible names are found in Bible lands to this day; but Book of Mormon names are not found in the Americas, therefore that book is fiction. That is the argument, every single step of which bears a misstatement of facts.

The first statement need not detain us long. Mr. Hancock asserts that “the names of men, cities, towns, countries and rivers are not translatable,” but that the same sound is given to them, as near as possible, in each language. Proper names, however, are translatable. Nathaniel means “the gift of God”; Baruk, “blessed”; Hagar, “flight”; Ramah, “high place”; Joshua, “God is salvation,” and so on. Modern names, too, have their meaning, and are, consequently, translatable. William, or Wilhelm, means a “golden helmet”; Rothschild, a “red shield”; Bountiful, Battle Creek, Salt Lake, are proper names with well understood meanings. In the ancient Maya language names such as Coh, Moo, Aac, Mayach, etc., are all translatable. In fact, all proper names have originally been translatable, although the meaning of many is now lost. Even the alphabet, if Mr. Plongeon’s theory is correct, is translatable. This is sufficient proof of how much reliability, the critic of the Book of Mormon names can have placed to his credit at the outset.

His second statement is hardly less unreasonable. “One can take the Bible,” Mr. Hancock says, “and go into Bible lands, there to find the names of men, countries, cities and rivers, just as given in that book from the remotest antiquity.” The author of that broad assertion would confer a favor upon the world by going into Bible lands and pointing out such places as Capernaum, Golgotha, Zoar and scores of other places about the location of which scholars can now only venture a guess. The fact is that some Bible names have been retained in Bible lands, while many have been entirely lost, and others have been changed beyond recognition.

The latter fact deserves special notice. The Bible has never been entirely lost It has been a force in human civilization in all ages; it has been read, studied with sacred reverence, and circulated by thousands, nay, millions of copies. And yet many of its most important proper names are almost eliminated from the vernacular of Palestine to-day. Jerusalem is no longer, in the language of the people there, Jerusalem, but El Kuds; Hebron is El Chalil; Jericho, Er Riha; Bethania, El Asarije; Sichem, Nablous; Samaria, Sebastije; Jezreel, Serin, Gath Heper, El Mschhed; Capernaum, Tell Hum; Damascus, Esh Sham, and so on. Thus names have changed even in Bible lands, and in spite of uninterrupted history. We are confronted by the same fact, if the names of the Bible are compared with the names of Bible lands as recorded in ancient secular inscriptions.

There is, for instance, a hieratic papyrus of the fourteenth century B.C., which contains a description of a carriage journey through Syria, made by an Egyptian officer, but the identification of the names, so scholars tell us, is “very dubious.” In some other records in cuneiform inscriptions the names Hazzatu, Ursallimmu and Samarina are found among others, supposed to be Gaza, Jerusalem and Samaria respectively. Thus names change. Hazzatu of the cuneiform inscription is Gaza in Gen. 10:19, while on modern maps it is Ghuzzeh. Jerusalem was once Ursalimmu, while to-day it is El Kuds.

What force is there, then, in the allegation that Bible names still remain in Bible lands? Some do, but a great many do not. But suppose that every copy of the Bible had been buried shortly after the destruction of Jerusalem, as the sacred implements of the ancient temple were once hid by a Prophet. Suppose the Christians had been previously all but annihilated by persecution. Suppose that the Bible lands had been overrun with Saracene and Arabic civilization minus the elements of Christian origin, and that finally a copy of the Bible had been found. Would it, under those circumstances, have been possible to identify a single Bible name? The fact that so many names have changed, notwithstanding every effort to preserve them, is sufficient reply to all these questions. Where would a modern scholar, with a newly-discovered Bible, lost for centuries, look for Canaan ? In the name Palestine there is no indication as to what region is meant by Canaan. Or where would he look for Mizraim? Could he guess that Egypt is the Old Testament Mizraim? What about Shur? What about such names as Tubal, Javan, Gog, Armageddon and others?

The third statement is a plain case of begging the question. Mr. Hancock says Book of Mormon names are not found in the Americas. To prove that, he gives an incomplete list of such names, and a still more defective list of ancient American names, and behold! because one mutilated list shows no resemblance to some fragments of another, therefore, one is a fraud. If this reasoning were applied to the Bible, that sacred record would also have to be pronounced fiction. From what has been said in paragraphs, it is clear that it would be easy to pick out half a hundred Bible names of cities, rivers and countries, and place beside them an equal number of modern or ancient names, totally different, though many of them would stand for the same places,. It is equally easy to make a similar experiment with names of persons. The following names are supposed to represent the same historical persons:

Bible Names: Secular Records:

Pul 3 Kin, 15:19 … Khinziros.

Merodach-Baladan, Is. 39:1 … Mardokempados.

Sargon, Is. 20:1 … Arkeanos.

Essar-Haddon, 2 Kings, 19:37 … Asaridinos.

Darius, Dan. 9:1 … Cyaxares.

Belshazzar, Dan. 7:1 … Labynetus.

This brief list is sufficient to show the nature of the disrcepancies between some Bible names and those on other records. What value, then, has the argument, against the Book of Mormon, founded on discrepancies in names? Were the history of ancient America as well known as is the history of Egypt, Assyria, Babylonia and Syria, those discrepancies might easily be accounted for.

The critic of the Book of Mormon should not lose sight of the history of that volume. According to the book itself, shortly after the deluge some members of the human family were brought to the Continent, where they became the bearers of their own peculiar civilization. These were the Jaredites. Six hundred years before Christ another colony came from the Holy Land and settled in South America. From this colony the Nephites and the Lamanites sprung. The two, although of one common stock, soon developed on different lines, somewhat similar to the two branches of the house of Abraham. A third colony also came to this hemisphere from Jerusalem shortly after the one just mentioned. It flourished for centuries, and was finally discovered by a party of Nephites, traveling northward.

Between the Nephites and the Lamanites there were constant wars, and the former were almost annihilated. Before this, however, the Prophet Mormon gathered the records of the people and copied them in an abridged form. Moroni, his son, finished this work, and hid the completed volume in the hill Cumorah. Nephi was, as he informs us, a Hebrew and Egyptian scholar, and without doubt the knowledge of these two languages was perpetuated as far as it was possible to do so while wars were raging, causing more or less unsettled conditions. When finally the compilation of the Nephite records was made, the vernacular had, naturally, been so modified that it was practically a new tongue.

With these facts before us it is plain that we cannot look for any large list of Book of Mormon names among the secular records of any one nation of American aborigines. As is to be expected, when the history of the book is considered, the early names of places and persons are of pure Hebrew or Egyptian origin. Lehi, Nephi, Melek, Sam, Ishmael, Gilgal, Gideon, Jerusalem, are instances of this. Later names show modifications and changes, some of which are difficult to account for at the present stage of American archaeological knowledge.

But Mr. Hancock assures us that “there is not a name in the entire Mormon list that bears the remotest resemblance to any of the ancient names of Central America.” The name Ishmael certainly closely resembles Uxmal, if it is remembered that X in the Maya language is the equivalent of the English Sh. It also resembles Izamal. Jacob and Ukub present another striking resemblance. Isaiah may be Itzaob. Imox (X pronounced as Sh) would not be much of a variation from Enos.

We may add a suggestion that the very name Cumorah, which at one time was called Rama, may be composed of Maya words. Without venturing assertions, we merely suggest that that proper noun might in Maya read Kumalaha, there being no R sound in that language. But according to Maya scholars, Ku means God; Mo, ma or me is place, earth. La is eternal truth, and ha is water. Kumalaha, or Cumorah, would then perhaps mean “the place of the truth of God, that has come from the other side of the water.” Rama, or Lama in Maya has nearly the same meaning: La, truth, and Ma, place—the place of truth.

We do not claim that it is at present possible to account for all the proper names in the Book of Mormon, but we do claim that the reasoning which stamps the volume as a fraud, because of the apparent difference between some of these names and some others which happen to be found on ancient monuments, is absurd. The same fallacious reasoning, if admitted as correct, would compel us to set aside the Bible as well as the Book of Mormon.—Deseret News.

Subject Keywords

Bibliographic Citation

Terms of use

Items in the BMC Archive are made publicly available for non-commercial, private use. Inclusion within the BMC Archive does not imply endorsement. Items do not represent the official views of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or of Book of Mormon Central.