Magazine

The Book of Abraham - Its Genuineness Established, Chapter IV

Title

The Book of Abraham - Its Genuineness Established, Chapter IV

Magazine

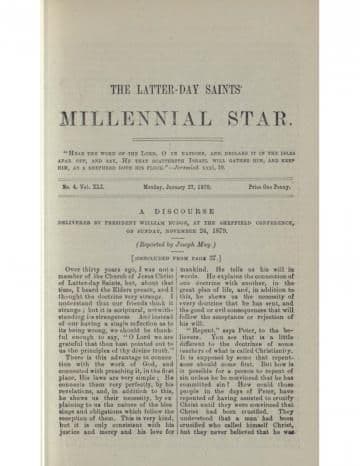

The Latter-Day Saints' Millennial Star

Publication Type

Magazine Article

Year of Publication

1879

Authors

Reynolds, George (Primary)

Pagination

53-55

Date Published

Jan. 27, 1879

Volume

XLI

Issue Number

4

Abstract

Abraham in Egypt.—Confirmatory Statements of Josephus, Nicolaus of Damascus, etc. —Abraham's influence on the Religions of Persia and Hindostan — Traces of Gospel teaching in the mythologies of the ancients.

THE BOOK OF ABRAHAM—ITS GENUINENESS ESTABLISHED.

BY ELDER GEORGE REYNOLDS.

[continued from page 19.]

CHAP. IV.

Abraham in Egypt.—Confirmatory statements of Josephus, Nicolaus of Damascus, &c—Abraham's influence on the Religions of Persia and Hindostan— Traces of Gospel teaching in the mythologies of the ancients.

The Book of Abraham states that God commanded the Patriarch to show unto the Egyptians the things that He hid revealed unto him. Josephus, in narrating this portion of Abraham’s history—being only partially acquainted with the facts of the case from the authorities at his disposal—tells us that Abraham went down into Egypt to avoid the famine in Canaan, and to “become an auditor of their priests, and to know what they said concerning the gods; designing either to follow them if they had better notions than He, or to convert them into a better way if his own notions, proved the truest.”1 After his arrival in Egypt, and the circumstances arising out of the attempt of Pharoah to add Sarai to the number of his wives, the out come of which placed the monarch under obligations to the Patriarch, Josephus states that “Pharoah gave Abraham leave to enter into conversation with the most learned among the Egyptians, from which conversation, his virtue and his reputation became more conspicuous than they had been before. For, whereas the Egyptians were formerly addicted to different customs, and despised one another's sacred and accustomed rites, and were very angry one with another on that account, Abraham conferred with each of them and confuting the reasoning is they made use of, every one for his own practices, he demonstrated that such reasonings were vain and void of truth; whereupon he was admired by them in those conferences as a very wise man, and one of great sagacity, when he discoursed upon any subject he undertook; and this not only in understanding it, but in persuading other men also to assent to him.”2 In another place the Jewish historian states “He (Abraham) was a person of great sagacity, both for understanding all things, and persuading his hearers, and not mistaken in his opinions; for which reason he began to have higher notions of virtue than others had, and he determined to renew and to change the opinion all men happened then to have concerning God.”3

So far as Josephus’ testimony, confirmatory of this portion of the Book of Abraham, is concerned we deem the above abundant. In later chapters we shall show the great political and religious changes that Abraham’s visits to Egypt produced.

From Egypt we will turn to Persia, and from the writings of various modern authors adduce testimony to prove that Abraham’s power as a religious teacher was felt, known and re cognized in the faith and creed of that nation.

In the sacred book of the ancient Persians and modern Parsees—the Zend Avista—“it is declared that the religion taught in it was received from Abraham; and according to Hyde, who supports his statements by quotations and references, this was believed by leading Arabian writers not only of Persian Magianism but of Indian Brahmanism.” The same writer remarks: “The claims of Magianism to have been influenced by the revelations made to Abraham are far from being discountenanced by the laws of historical probability. For the war waged so successfully by Abraham in behalf of his kinsman, Lot, against the five kings, among whom was the king of Elam (i.e. Persia) is of itself a sufficient proof that the father of the faithful, Abraham, the Hebrew from Ur of the Chaldees, must have been as well known to the eastern kingdoms as Moses was in after times.4

It is generally admitted that in the days of Abraham the forefathers of the Persians and Brahmins were one people, inhabiting one region of country. It is supposed that the ancestors of the latter race moved to India from 1,500 to 1,300 years B. C. That these two races are of common descent is urged from the close relationship existing between the Sanskrit, the language of the Brahmins, and the Zend or Persian; it is also said that the remarkable identity between the Brahminical and Persian mythologies indicates, unerringly, the original union of the two.” It may also be noticed that Hitzig, in his “Geschichte des Volkes Israel,” reasons from the identity of certain practices observed by Abraham and the Patriarchs of Israel on the one hand, and by Brahminical Hindoos on the other, that a community of some kind once existed between these people.

The two nations being thus admitted by authors of research, to have been one people in Abraham’s time, it is supposable that the Brahmin as well as the Persian branch of the family would exhibit some traces of Abraham's ministry. On this point it has been written “Abraham’s influence extended to Bactria, and the most complete proof at once of its spread, and the spread with it of the name and renown of Abraham, is contained in the language and name of the Brahminical Hindoos.”5

“The name Brahma signifies he who multiplies, the name Abraham likewise means the father of a multitude,” (Arabec. Rahama, a multitude. Gen. xxii, 5). The wife of Brahma was named Savitree. The wife of Abraham was named Sarai or Sarah.”6

Mr. Goodsir, remarking on this last extract, writes: “These coincidences appear to us to be well deserving of attention, though we are not aware that they have ever before been noticed. We leave them and the whole question of the identity of Brahma and Abraham to the judgment of our readers, merely observing, in conclusion, that, having found Adam and Noah and Ham to have been the father gods of Egyptian mythology, and Japhet the father-god of that of Greece, there is abundant analogy as well as probability in our inference that the father-god of the Indian superstition was Abraham.”

Admitting the truth of the following extract from the writings of Nicolaus of Damascus, referred to by Josephus, it is very easy to understand when and how Abraham obtained his great influence in Persia; and we know of no conflicting testimony, to render the statements unworthy of our consideration. He writes, in the fourth book of his history, “Abram reigned in Damascus, being a foreigner, who came with an army out of the land above Babylon, called the land of the Chaldees; but after a long time he got him up and removed from that country also, with his people and went into the land, then called the land of Canaan, but now the land of Judea … Now the name of Abram is even still famous in the country of Damascus, and there is shewed a village named from him, the habitation of Abraham.”

We now come to the cons ide ration of the traces, oft times scarcely discernible, found in the pagan religions of the ancient nations of the eastern continent, of a time when the worship of the true God was taught and under stood in their midst, for we fully believe that having made of one blood all the nations of the earth, “God guided and ruled over pagan nations in a manner, the same in kind, though much modified in degree, as in the case of the chosen people; and for the same great final end.” Let it not be supposed, in the following pages, that we desire to extenuate the sinfulness, or to palliate the foulness of idolatrous, cruel, unclean and licentious paganism in any of its branches. Our desire is to exalt the goodness of God, as well as to show that under all the vileness, the indecency, the lust and cruelty of many of the forms of ancient paganism could be found a sub-stratum of pure revealed truth, testifying to us that, at some period, the fathers of these peoples held intercourse with the servants of the true God, but had fallen away from the principles of righteousness aforetime taught them, and after their own peculiar ways and to suit their own peculiar notions and desires had heaped to themselves gods and demons, creeds and rites, ceremonies and mysteries, oracles and auguries, differing in different nations, according to the force of circumstances and the direction given to them by master minds.

As a proof of the truth of our position, we have but to refer to the fact, that it has been demonstrated that the further we go back through the centuries to the primeval days, succeeding the dispersion of mankind at the Tower of Babel, the more frequent and more noticeable are the traces of pure religious truth found intermingled with the follies and vagueries of man-made religions. As an example of this it is recounted by Levy, the Roman historian, that certain sacred books having been found at the burying place of Numa, the great religious legislator of early Rome, they were burned because they were not suited to the times in which they were discovered, when Rome had added scores of gods to its Pantheon, though they were considered suited to the early era in which they were written, when Numa forbade images and their worship as well as the offering of human sacrifices.

Subject Keywords

Bibliographic Citation

Terms of use

Items in the BMC Archive are made publicly available for non-commercial, private use. Inclusion within the BMC Archive does not imply endorsement. Items do not represent the official views of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or of Book of Mormon Central.