Magazine

Ancient Cities of Arizona

Title

Ancient Cities of Arizona

Magazine

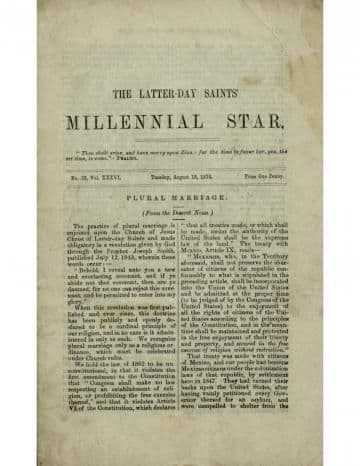

The Latter Day Saints' Millennial Star

Publication Type

Magazine Article

Year of Publication

1874

Editors

Smith, Joseph F. (Secondary)

Pagination

516–518

Date Published

18 August 1874

Volume

36

Issue Number

33

Abstract

This article considers a chain of ancient cities located about a mile apart in Arizona and New Mexico and the artifacts found there. It looks at their sophisticated tools, reservoirs, place of worship, and other items.

ANCIENT CITIES OF ARIZONA.

The ruins of the ancient cities of Southern Arizona are just now attracting considerable attention. Until recently the only information that has come to the surface has been that obtained from adventurers, who, while passing through that section in search of gold, have jotted down that which forced itself upon their vision during their hasty transit. Many of these stories have contained such marvelous statements that they have been cast aside as cleverly written pieces of fiction, as the writers were unknown. The murderous Apaches are gradually giving way before the advance of civilization; are being hurled back into their mountain retreats; into eternity and on to reservations by General Crook and his soldiers, and that most wonderful country is soon to teem with the life and industry of white men. Arizona is known to be one of the richest mineral bearing countries in the world, and her valleys contain a remarkably productive soil, under the influence of irrigation.

Mr. J.A. Parker Superintendent of the Montezuma Canal Company, whose works are located in Pueblo Viejo Valley, Arizona, has arrived in this city and from him we have obtained a fund of information relative to that country. The Pueblo Viejo Valley lies south of and bordering on the Gila River, and between it and the Graham range of mountains. It is about 400 miles east of Yuna, thirty miles north of Camp Grant, and sixteen miles west of the New Mexico line. This valley is about sixty miles long and averages four miles in width, and contains as fine agricultural and grazing land as can be found anywhere. About a year ago four companies commenced the construction of irrigation canals at this point, and have now completed from three to six miles each of their works.

In this beautiful and fertile valley is a chain of well-marked ruins of ancient cities located about a mile apart. In some places the walls of the houses still show above the surface, and at others the rolling mounds, from ten to forty feet in height, covered with earth and vegetation, show that ages must have passed since they were laid prostrate. Mr. Parker, who is a man possessed of an inquiring turn of mind, and is backed by literary attainments of a high order, has devoted most of his spare time during the last year in researches among these ancient ruins. The walls are composed of rough stone, laid in mortar. Excavations within their limits indicate that all the cities were destroyed by fire.

Among the debris are found pottery, household utensils and human bones; but as yet no warlike implements have been brought to light, The human bones show unmistakable evidence of having been burned, and crumble to pieces upon being handled. Several ollas (pronounced o-yahs)—jug-shaped earthen vessels now used by the Indians for holding water—were found, which contained ashes, small pieces of human bones and fragments of charcoal, which would indicate that cremation was practiced by that extinct people. Axes, hammers and sledges of various sizes and shapes, and made from stone which is much heavier and harder than any now known of have been brought to light. One of these axes, found by Mr. Parker, was tested by him. He cut a rod of iron in two with it, and no perceptible effect was produced upon the axe by the operation. This relic has been sent to the World’s Fair for exhibition.

Mr. Parker has quite an extensive collection of pieces of pottery which he dug out of these ruins. He brought with him to the city several specimens, which ho has presented to the Alta. The vessels were evidently made of clay, which is now of a dark gray color and as hard as stone. The surfaces are nicely glazed and covered with lines and characters of different colors from the work. One piece has a black surface, covered with yellow, irregular lines, and surrounded by a similar colored border of wedge-shaped characters. Another piece is covered with white and black figures, the lines being more regular than in the other piece, and containing on its surface what is known among printers as a “Roman border,” outside of which are serrated rows of black and striped lines, the whole being surrounded by circular lines of white and black.

Among the collection before us is a white, translucent stone, which looks as if it had bubbled out from a seething mass of the same material. It is flinty in character and will cut glass. There are three smaller stones of the same variety, each containing a crimson hue, the smaller being quite red and brilliant. Besides these there are two pebbles of ebony hue externally, but which upon being held up to the light are perfectly transparent. One of them has been broken in two, and the surface presented is as smooth and brilliant as that of a polished crystal.

A careful examination shows that there is a large canal extending from the Gila River, at the eastern end of the valley, down through these ancient cities, in each of which is found a large triangular-shaped reservoir, and containing from three to five acres. These reservoirs have been reported by parties who have made but a casual examination of them, as the ruins of old fortifications. The edges of the canal and reservoir are laid with stone, and are constructed in a very substantial manner. Some of the reservoirs, which were six or eight feet deep, are cut in two by walls of masonry extending from side to side.

On the bank of the Gila River, or about ten miles below Florence, are the ruins of a most singular structure— a building fifty-one by fifty-seven feet, built of adobie, which is now so hard that a pick cannot be driven into it. There are two walls—a building within a building—which are separated about ten or twelve feet, and which are between twenty-eight and thirty inches thick at the base. In the walls, up about nine feet, and extending entirely around the structure, was placed at the time the building was put up, a row of cedar beams, which probably served to brace and strengthen the building. The ends of these timbers, which are still in a fair state of preservation, show that they were consumed by fire, up to and, in some instances, part way through the wall. There are now three stories of the walls still standing, in one place, The windows are long and narrow, and seem to have been placed where they were needed, and without regard to external symmetry. The doors are at the corners. At the top of the inside wall are several round holes, about the size of a hat. The art of plastering seems to have been perfect in those days, as the inner wall is still smooth and of a yellowish white color. What this building was used for can only be conjectured, as it stands in an open space surrounded by the same class of ruins as those above referred to. It is probable that it was a church, or, if that people did not worship God, idols may have received adoration there.

Near this building, and at other points among these ruined cities, are still standing rows of cedar posts, set on very accurate lines. The upper ends of these posts look old, and have been worn by the elements, still they are in a good state of preservation. The portions that are in the ground are much larger, and are very little affected by age.

The same class of ruins described above can be found all over Southern Arizona, New Mexico Territory, and the northern part of Mexico, wherever there are fertile valleys and flowing streams. Little or nothing is known of the people who built these cities or when they existed. The Indians say that long ago the inhabitants of these places were summoned off to the south, and engaged in a battle in which they were all killed. They probably derived this story from the early Americans or Mexicans who visited this section and, seeing the ruins, concluded that they were formerly occupied by one of the semi-civilized tribes with whom Montezuma, the Mexican king, made war, and perhaps plundered their cities and burned them. This is simply conjecture. If these were the facts, as Montezuma kicked up his troubles about 360 years ago, we would probably have had some account of it. And then, again, there are, we believe, no such pottery and household implements in Mexico as have been found in the Arizona ruins.

The theory that the wanderers through Asia, about 1,000 or 1,500 years ago, crossed Behring Strait and made their way down the Pacific coast of this Continent into the temperate and torrid zones, may and possibly does come nearer to offering an explanation. But what has become of their race and its history? Were both blotted out at once, and if so, by whom? Now, that the bloody Apaches are being subjugated and exterminated, a fine opportunity is offered for academies of natural science, and men with money to expend for the enlightenment of mankind, to encourage the exploration of these ancient buried cities, and to bring to light what has been enveloped in mystery? Who will be the first to move in this matter? —Alta California.

Subject Keywords

Bibliographic Citation

Terms of use

Items in the BMC Archive are made publicly available for non-commercial, private use. Inclusion within the BMC Archive does not imply endorsement. Items do not represent the official views of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or of Book of Mormon Central.