Magazine

American Antiquities: Corroborative of the Book of Mormon (4 February 1860)

Title

American Antiquities: Corroborative of the Book of Mormon (4 February 1860)

Magazine

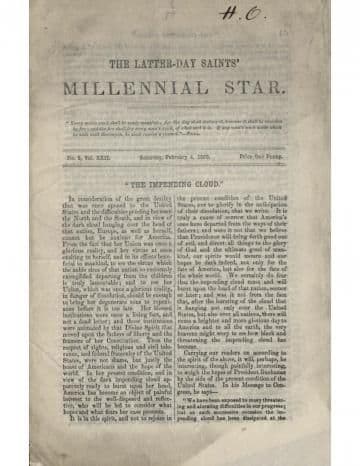

The Latter Day Saints' Millennial Star

Publication Type

Magazine Article

Year of Publication

1860

Editors

Lyman, Amasa (Secondary)

Pagination

77–78

Date Published

4 February 1860

Volume

22

Issue Number

5

Abstract

This 47-part series provides evidence to confirm the authenticity of the Book of Mormon. It describes the contents of the Book of Mormon and archaeological findings and discoveries, such as ancient cities, temples, altars, tools, and wells. Each part contains several excerpts from other publications that support the Book of Mormon.

AMERICAN ANTIQUITIES,

CORRORATIVE OF THE BOOK OF MORMON.

(Continued from page 63.)

(From Wilson's “Mexico and its Religion,” &c., published in London 1856.)

“We have removed to a greeter antiquity, but have not got rid of the question of the origin of Mexican civilization. The year 600, named by Humboldt, may be considered as the time of their appearance on the table-land; but many of the ruins in the hot country might claim a thousand years earlier antiquity. These massive remains must have stood, abandoned as they now are, in the midst of the forest, for a long time before the Conquest, as their very existence was unknown to the Spaniards until near the close of the last century.’’

(From Madden’s “Shrines and Sepulchres of the Old and New World,” published in London in 1851.)

“Mr. Harriss, a member of the Massachusetts Historical Society, gives an interesting account of the ancient graves which are scattered over the whole face of the western country of America:— 'The places called graves are small mounds of earth, from some of which human bones have been taken. In one were found the bones, in their natural position, of a men buried nearly east and west, with a quantity of isinglass (mica membranea) on his breast: in others, the bones laid promiscuously; some of them appeared partly burned and calcined by fire; also stones evidently burned, charcoal, arrow-heads, and fragments of a kind of earthenware. An opening being made at the summit of the great conic mound, there were found the bones of an adult, in a horizontal position, covered with a flat stone. Beneath this skeleton were three stones placed vertically, at small and different distances; but no bones were discovered. That this venerable monument might not be defaced, the opening was closed without further search. It is worthy of remark that the walls and mounds were not thrown up from ditches, but raised by bringing the earth from some distance, or taking it up uniformly from the surface of the place. The parapets were made probably of equal height and breadth; but the waste of time has rendered them lower and broader in some parts than others. It is in vain to conjecture what tools or machinery were employed in the construction of those works; but there is no reason to suppose that any of the implements were of iron. Plates of copper have been found in some of the mounds, but they appear to be parts of armour. Nothing that would answer the purpose of a shovel has ever been discovered.’"

(From Hill's “Travels in Peru and Mexico,” published in London in the present year of 1860.)

“It is not possible to travel in Peru without having the mind constantly occupied with the consideration of what more concerns the ancient inhabitants than the present possessors of the country. … The accounts, however, given by the Peruvians concerning the origin and progress of the civilization they had attained before the arrival of the Spaniards, have been justly considered by the author of the ‘History of the Conquest of Peru’ as mere fable, partly because they cover a period too long to have been occupied by the reign of only thirteen Incas, which is the number mentioned in their history, and also on account of the discovery of the ruins of great edifices on the shores of the lake Titicaca, which are acknowledged by the Peruvian historians to have been erected before the reign of the first Inca. It appears, indeed, certain that a race of men considerably advanced in civilization must have existed in Peru before the time of the Incas. … After mounting a steep and winding pathway on the western side of the city, [Cuzco,] we first came to a terrace, upon which are the remains of the palace of the first Inca, Manco Ccapac, or such as are so called; for the truth of the prevailing opinion has been doubted by several Spanish historians, which has led, indeed, to curious conjectures concerning the origin of Peruvian civilization. … This remarkable relic of a former age is situated immediately below the heights upon which are found the remains of the great fortress we were about to visit. It consists chiefly of a wall of about twelve feet in height, which stands upon a firm terrace paved with smooth stones of irregular forms and sizes, but fitted to one another in the same manner as those in the walls of the buildings of the ancient town. … After entering the open doorway upon the terrace, we mounted some stone steps which brought us to a cultivated field on a level with the front wall. On the inner side of this are found massive ruins of ancient edifices, amongst them are the remains of a wall of about thirty feet in length, and eight or ten feet in height, the stones in which are placed with the same exactness as in the temples below. Other remains of buildings were also strewed about on the same side of the hill we were ascending, which, although they do not seem to have any connection with one another, are all supposed to have belonged to the establishment of the first Inca. … We reached Chdincheroa, an Indian village at the distance of five leagues from Cuzco, containing about 300 inhabitants. During a short stay which we made here, we observed that there were three distinct masses of ruins, besides the wreck of many other ancient buildings distributed about the place. … The ruins which it was the chief object of my expedition to inspect were at Ottantaitambo, less than half a day’s journey further. … Innumerable ruins of stone buildings were distributed everywhere in the most thorough confusion. … The whole of the ruins were strewed about in as much confusion as if an earthquake had distributed them. Neither the bounds of the particular dwellings nor the form or size of any one of them could be distinguished."

(To be continued.)

Subject Keywords

Bibliographic Citation

Terms of use

Items in the BMC Archive are made publicly available for non-commercial, private use. Inclusion within the BMC Archive does not imply endorsement. Items do not represent the official views of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or of Book of Mormon Central.