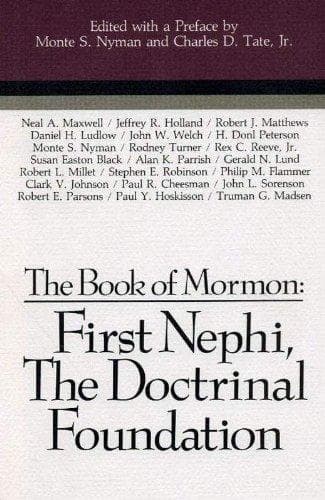

Book

21 Chapters

Paul R. Cheesman

Paul R. Cheesman was professor emeritus of ancient scripture at Brigham Young University when this was published.

The story of the Book of Mormon and Lehi’s exodus from the Old World begins in Jerusalem, the capital of the kingdom of Judah and the most prominent city in all Israel. Latter-day Saint visitors to Jerusalem, who are inspired by these surroundings as they relate to the life of Christ, should also remind themselves that this is where the prophet Lehi lived. In Lehi’s time, priests and Levites who officiated in the ordinances of the law of Moses, worshippers from the other tribes of Jacob, merchants from Egypt and neighboring countries, and artisans in various trades—all considered Jerusalem a center of civilization in the Near East.

The country was divided into two parties—pro-Egyptian and pro-Babylonian. Most of the people favored the Egyptian influence. Hugh Nibley has suggested that Lehi had been closely associated with Egypt as a merchant and thus had traveled between the two countries. [1] This experience would have been a great advantage to Lehi for the journey that he was eventually commanded to undertake. Lehi probably spoke and wrote Egyptian, which he taught his sons. [2]

The story of Lehi’s leading the company of Israelites from Jerusalem to America is told in 1 Nephi 2–18. Many of these chapters, however, deal with Nephi’s visions (1 Nephi 11–15) and his comments on the records he is keeping (1 Nephi 6, 9). That leaves about twenty-five pages wherein the group’s travels are recorded, and most of these pages record opposition of the elder sons Laman and Lemuel to their father and younger brother Nephi. The result is that we have only a sketchy account of Lehi’s travels given us in the Book of Mormon. We are therefore left to surmise several related things based upon consideration of other evidences.

That Lehi lived in Jerusalem did not necessarily mean that he dwelt in the city of Jerusalem. The land of Jerusalem encompasses much more of the immediate area surrounding the city. We are of the opinion that Lehi’s property lay somewhere in the land of Jerusalem and not within the walls of the city.

Lehi was of the tribe of Manasseh and was obviously a man of considerable wealth (Alma 10:3–4). He and his wife, Sariah, had four sons and some daughters. He received many dreams and visions in which the Lord instructed him to warn the people of Jerusalem to repent. Rather than listen and repent, the people were angry with Lehi and sought his life. As a result, he was commanded to leave Jerusalem. He went into the wilderness and left behind great treasures of gold, silver, and other precious items, carrying with him only the necessities for traveling and existing in the wilderness (1 Nephi 2:4).

Lehi’s wealth seemed to reflect the possibility of his being a trader, acquiring all manner of “precious things” (1 Nephi 2:4, 11). We can assume that he was an experienced traveler because his preparation for the trip into the wilderness was so complete that he did not have to send back for any provisions. Nibley reminds us that Manasseh was the tribe living in the most remote part of the desert. [3]

There are three possible routes from Jerusalem to the Red Sea: (1) from Jerusalem northeast to Jericho, east across the Jordan River, and then south on the east side of the Dead Sea; (2) from Jerusalem to Jericho and down the west side of the Dead Sea; and (3) from Jerusalem southwest through Hebron, then east or southeast to a point below the Dead Sea. All three routes converge south of the Dead Sea and lead to Aqaba.

Lynn M. and Hope Hilton have suggested that Nephi could have seen metal smelting and shipbuilding at Aqaba that would have benefited him later. [4] From Aqaba Lehi’s group journeyed “three days in the wilderness” and camped in the “valley of Lemuel” (1 Nephi 2:10, 14). After traveling in this area, the Hiltons conclude that the valley of Lemuel is most probably the place now known as Al Beda in the Wadi El Afal, in Saudi Arabia. Al Beda contains the ruins of what has been considered the traditional home of Moses’ father-in-law Jethro. The ruins are still called by his name. Lehi’s colony could have stayed at Al Beda several seasons. [5]

In this valley Lehi built an altar and offered a sacrifice to the Lord, giving thanks for their journey. His description of the valley’s being firm and steadfast and immovable is in contrast to the modern vernacular of Joseph Smith, who probably would have referred to the mountains and hills as the everlasting and stronghold areas. To the Arabs, the valleys, not the mountains, are the source of their strength and permanence. [6]

It seems to be a tradition among Semitic people to name even already-known places after their current personal experiences, perhaps to give greater meaning to the areas. [7]

It was in the valley of Lemuel that Lehi had a dream commanding him to send his sons back to Jerusalem to obtain the brass plates. After a successful mission, the sons returned with the brass plates and also with Zoram, the servant of Laban, who was the keeper of the plates. [8]

Nephi had made Zoram take an oath that he would not return to Jerusalem. One might consider this a strange custom, but to the people of that day there was “nothing more sacred than the oath among the nomads.” [9] Such action supports the Book of Mormon as an ancient Israel document.

The Lord also counseled Lehi to have his sons return to Jerusalem a second time to bring the family of Ishmael, who was of the tribe of Ephraim, to join them on their journey. Again the mission was successful and the family of Ishmael, including his sons and their wives and children, plus Ishmael’s single daughters, left Jerusalem and joined the family of Lehi in the wilderness. This allowed the sons of Lehi the opportunity for marriage and family.

According to Erastus Snow, Joseph Smith said that Ishmael’s “sons [had] married into Lehi’s family.” [10] This combination of families would increase the number who continued the journey to approximately twenty to thirty people, depending on the number of children among them. This number increased during this eight-year wilderness journey as two sons, Jacob and Joseph, were born to Sariah and Lehi (1 Nephi 18:7), and other families also bore children (1 Nephi 17:1, 20).

The Book of Mormon indicates that after the group left the valley of Lemuel, they traveled for the space of four days in a “south-southeast direction” (1 Nephi 16:13). Most researchers believe that the trail Lehi took was near or on the passage most commonly taken by travelers, and known as the Frankincense Trail. It is reported that Joseph Smith was of the opinion that Lehi’s party “traveled nearly a south-southeast direction until they came to the nineteenth degree of north latitude; and then nearly east to the sea of Arabia.” [11] The exact route is not known. It was revealed to Lehi where he was to go, and so it is not possible or necessary to establish the exact route.

Reynolds suggests that the ancient Aztec map known as the Boturini Codex bears certain figures in hieroglyphic drawing which might depict Lehi’s travels. [12]

The Lord gave directions through “a ball of curious workmanship” (1 Nephi 16:10), which Nephi refers to as a compass (1 Nephi 18:12). Alma records the name of the instrument as the Liahona (Alma 37:38). But the Liahona should not be compared to a mariner’s compass. Lehi’s “compass” indicated the directions in which Lehi should go; the mariner’s compass only tells the traveler which way is magnetic north. The Liahona worked on the principle of faith and according to the diligent attention given to it (Alma 37:40). Mosiah refers to it as a director (Mosiah 1:16). It not only gave directions to the travelers, but writing also appeared on the ball (1 Nephi 16:26).

It is believed by some that the word Liahona means “To God Is Light”; that is to say, God gives light as does the sun. [13] The unique quality of the Liahona was in providing spiritual guidance as well as travel direction.

It was approximately eight years from the time the Lehi colony left the valley of Lemuel until they reached a place they called Bountiful. Since they carried seeds of every kind, we can suppose they took time to plant along the way and also wait for the harvest before proceeding. This would mean that their travels may have been seasonal. Perhaps they traveled in the cooler months of the year. It is estimated that their trip to the Arabian Sea was somewhere near twenty-five hundred miles in length.

The company would probably travel for a few days, rest, hunt, and then take up their journey as the Liahona directed. Perhaps when they found good soil and water they would plant seeds and harvest the crops.

The food eaten on this trip probably consisted of their own crops and probably grapes, olives, and figs, which grow in the area, and also meat (1 Nephi 16:31; 17:1–2). Other fruits which are grown in the Middle East and could have been used include dates, coconuts, and pomegranates.

An average encampment was calculated to be about twelve days long, but some crop-growing ones were perhaps as long as six months. [14] How fast did the Lehi company travel? Major R. E. Cheesman, an experienced traveler in that area in the 1920s, has estimated that the average caravan could travel thirty miles a day. [15]

During this journey, the group also may have fished along the coasts of the Red Sea, as this body of water contains mackerel, tuna, sardines, and horgie. [16]

On the probable trail which Lehi traveled there are today 118 waterholes, spaced (on the average) eighteen miles apart. [17] It was the custom of experienced travelers in Arabia that they never built a fire, as it could attract the attention of a prowling, raiding party. [18] As a result, they ate much of their food raw, as recorded in the Book of Mormon (1 Nephi 17:2). Attacking and plundering camps still seems to be the chief object of some Arab tribes.

Lehi’s journey, besides being difficult because of the terrain, also became troublesome because of the constant rebellion of Laman and Lemuel and some of Ishmael’s children.

It seems that the keynote of life in Arabia is and was hardship. Albright notes concerning the general area where we know Lehi had traveled that it is a land of “disoriented groups and of individual fugitives, where organized semi-nomadic Arab tribes alternate with . . . sedentary society, with runaway slaves, bandits, and their descendants.” [19]

How did they travel through this difficult terrain and environment? From all observations, camels seem to be the mode of travel. No matter which route Lehi took to the Red Sea, he would have encountered camel markets which would have allowed him to use this animal even if he started only with donkeys. Camels can take two 150- to 180-pound packs on their backs, and Lehi brought his tents, provisions, and seed with him to plant and harvest en route and to use in his promised land. Although the Book of Mormon does not mention camels, it may be that they were not mentioned because they were taken for granted.

After traveling four days from the valley of Lemuel, the company camped in a place they called Shazer (1 Nephi 16:13). Calculating their average traveling distance, this place could be the modern oasis of Azlan in the Wadi Azlan. Even another harvest season could have elapsed in this area. Because of the spelling and pronunciation of similar place names in Palestine, Nibley proposes that this could have been a name given to a place where trees grew. [20]

After leaving Shazer, the narrative indicates that Nephi broke his bow and the colony was desperate for food (1 Nephi 16:18ff). Nephi found wood to build a new bow (1 Nephi 16:23). Archaeologist Salim Saad calls our attention to the fact that wood from the pomegranate tree which grows around a place called Jiddah would make a good bow. These particular trees, with especially hard wood, were an absolute necessity for bow-making purposes. Evidently the areas where Nephi could have found wood suitable for a bow were not plentiful, hence the need for divine guidance at this point in the journey. It was also providential at this point that this area contained many animals suited for food. [21]

Nibley cites another witness to the building of a new bow. According to Arab writers, the only bow wood available grew near the mountains of Jasum and Azd. [22] As nearly as we can surmise, this is where the Lehi group was encamped when Nephi broke his bow and sought to make another (1 Nephi 16:23). Jiddah is also a shipbuilding city and perhaps Nephi could have observed craftsmen in this area which would have benefited him later.

Moving on in the same easterly direction, they came to a place that was called Nahom. It was not named by Lehi but was apparently a desert burial ground. It was here that Ishmael died and was buried (1 Nephi 16:34). Nibley explains the possibility that the name Nahom is related to an Arabic root word meaning “to moan.” When Ishmael died, the “daughters of Ishmael did mourn exceedingly” (1 Nephi 16:35). It seems that among the desert Arabs, mourning rites are monopolized by the women. [23] A possible site of Nahom where Ishmael was buried is thought by the Hiltons to be al Kunfidah in Arabia. Rows of graves found in Al Kunfidah sustain the possibility that it was an ancient burial ground. [24]

After traveling in an easterly direction, as the Book of Mormon indicates (1 Nephi 17:1), the party went through an area where they “did wade through much affliction.” This arid wasteland was perhaps the worst desert of all. It did merge, however, into a paradise by the sea which they named Bountiful. There is just such an area in the Qara Mountains on the southeasterly coast of Arabia. There is one place in the entire fourteen-hundred-mile southern Arabian peninsula that meets the description of Bountiful in the direction from Nahom suggested in the Book of Mormon and by the Prophet Joseph Smith as noted earlier (note 12). This is modern Salalah. They called the new land “Bountiful, because of its much fruit and also wild honey” (1 Nephi 17:5). Hilton reports that today in Salalah a person finds many fruits growing—citrons, limes, oranges, dates, bananas, grapes, apricots, coconuts, figs, and melons. [25]

It was at Bountiful where Nephi was commanded to build a ship (1 Nephi 17:7–8). The Lord himself instructed Nephi on the details of building the ship that carried the Lehi colony to the promised land. It must have been a unique structure, since we are told that it was not built after the manner of men (1 Nephi 18:1–2). Consequently, we cannot compare it to the traditional ships built in that time period. Even Nephi’s brethren remarked on the workmanship as being unusually good (1 Nephi 18:4). Even though building a ship was a new experience for Nephi, he surely would have observed native shipbuilders in the many villages he passed as he traveled along the coast of the Red Sea.

The sycamore-fig shade tree that grows in the desert produces a very hard wood, is strong, resistant to water, and almost free from knots. These trees still grow in the area of Salalah, where Nephi might have been when he was instructed to build his ship. Surely the wisdom of the Lord was involved in the selection of areas where the Nephites lived in the wilderness as he directed their journey via the Liahona.

Because of the length of time involved in this exodus—eight years to make the journey from the valley of Lemuel in addition to the years required for building the ship—the number in Lehi’s extended family could have enlarged to as many as forty or fifty people. If the numbers were that high, the ship would have had to be at least sixty feet long to accommodate such a large group, especially if there was enough space for dancing, which the record states that they did (1 Nephi 18:9). The ship was built and the people sailed for the promised land.

The weather and geography of Arabia have changed little, if any, since Lehi’s day. [26] Most LDS scholars are of the opinion that current studies of Arabic geography and history are in complete harmony with Lehi’s story. [27] It is also the opinion of those who have traveled and studied the area involved in Lehi’s exodus that everything recorded in 1 Nephi concerning the travels of Lehi actually could have happened. [28]

With the passing of time and with continued study, the case for the Book of Mormon record will increase in strength. I can foresee the day when the world of scholarship and archaeology in academic circles outside the Church will continue to uncover and unearth such thrilling evidences that the world will be left without excuse. It is my hope that all of our endeavors will be in studies that will sustain and support the truth in this marvelous record of Lehi’s extended family. It is my desire to eliminate obstacles so that the student and scholar will become so impressed and fascinated with this sacred record that they will eventually open the Book of Mormon, read it, and gain a testimony of its eternal truths.

[1] Hugh W. Nibley, Lehi in the Desert and the World of the Jaredites (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1952), pp. 8, 12–13, 36–38.

[2] Although Lehi wrote Egyptian as well as Hebrew, the language of the Book of Mormon was Reformed Egyptian, a combination of Hebrew and Egyptian that was known only to the Nephites; see 1 Nephi 1:2; Mosiah 1:4; Mormon 9:32–33.

[3] Nibley, Lehi in the Desert, p. 41.

[4] Lynn M. Hilton and Hope Hilton, In Search of Lehi’s Trail (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 1976), p. 39.

[5] Ibid., p. 74.

[6] Nibley, Lehi in the Desert, p. 105.

[7] Hilton and Hilton, p. 27.

[8] This record contained the first five books of the Bible and other biblical books to the time of Jeremiah (1 Nephi 5:1–14). It documented God’s dealings with his covenant people. When these young men were asked to return to Jerusalem to obtain the brass plates, the idea of records being kept on metal plates certainly was not new or strange to any of them. For a treatise of evidence that ancient records were kept on metal plates, see Paul R. Cheesman, Ancient Writing on Metal Plates (Bountiful, Utah: Horizon Publishers, 1985), p. 85.

[9] A. Janssen, “Judgements,” Revue Biblique XII (1903), 259 CF Surv. Wstn. Palest., p. 327, as quoted in Nibley, Lehi in the Desert, p. 118.

[10] Erastus Snow, Journal of Discourses, 23:184.

[11] B. H. Roberts, New Witnesses for God, 3 vols. (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1951), 3:501–3. “In a compendium of doctrinal subjects published by the late Elders Franklin D. Richards and James A. Little, the following item appears: ‘Lehi’s travels.—Revelation to Joseph the seer: The course that Lehi and his company traveled from Jerusalem to the place of their destination: They traveled nearly a south, southeast direction until they came to the nineteenth degree of north latitude; then, nearly east of the Sea of Arabia, then sailed in a southeast direction, and landed on the continent of South America, in Chili, thirty degrees south latitude.’

The only reason so far discovered for regarding the above as a revelation is that it is found written on a loose sheet of paper in the handwriting of Frederick G. Williams, for some years second counselor in the First Presidency of the Church in the Kirtland period of its history, and it follows the body of the revelation contained in Doctrine and Covenants, section vii., relating to John the beloved disciple, remaining on earth, until the glorious coming of Jesus to reign with his Saints. The handwriting is certified to be that of Frederick G. Williams, by his son Ezra G. Williams, of Ogden; and endorsed on the back of the sheet of paper containing the above passage and the revelation pertaining to John. The indorsement [sic] is dated April, the 11th, 1864. The revelation pertaining to John has this introductory line: “A Revelation Concerning John, the Beloved Disciple.” But there is no heading to the passage relating to the passage about Lehi’s travels. The words “Lehi’s Travels,” and the words “Revelation to Joseph the Seer,” are added by the publishers, justified as they supposed, doubtless, by the fact that the paragraph is in the handwriting of Frederick G. Williams, Counselor to the prophet, and on the same page with the body of an undoubted revelation, which was published repeatedly as such in the life time of the Prophet, first in 1833, at Independence, Missouri, in the “Book of Commandments,” and subsequently in every edition of the Doctrine and Covenants until now. But the one relating to Lehi’s travels was never published in the life-time of the Prophet, and was published nowhere else until published in the Richards-Little’s Compendium.

[12] George Reynolds and Janne M. Sjodahl, The Story of the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1955), pp. 10–11.

[13] Daniel H. Ludlow, A Companion to Your Study of the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 1976), p. 113.

[14] W. E. Jennings-Bradley, The Bedouin of the Sinaitic Peninsula, PEFQ, 1907, p. 284.

[15] Cheesman, In Unknown Arabia, pp. 27, 52.

[16] Hilton and Hilton, p. 90.

[17] Ibid., p. 33.

[18] Cheesman, In Unknown Arabia, pp. 228, 234, 240, 280.

[19] W. F. Albright, Archaeology and the Religion of Israel (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1942), p. 101.

[20] Nibley, Lehi in the Desert, p. 90.

[21] Hilton and Hilton, pp. 81–83.

[22] Nibley, Lehi in the Desert, p. 68.

[23] Ibid., pp. 90–91.

[24] Hilton and Hilton, p. 95.

[25] Ibid., p. 105.

[26] Ibid., p. 116.

[27] In addition to Hugh Nibley and the Hiltons, see Eugene England, “Through the Arabian Desert to a Bountiful Land: Could Joseph Smith Have Known the Way:” in Book of Mormon Authorship: New Light on Ancient Origins (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Religious Studies Center, 1982), pp. 143–56.

[28] 28. Nibley, Lehi in the Desert, p. 129.

Book

21 Chapters

Items in the BMC Archive are made publicly available for non-commercial, private use. Inclusion within the BMC Archive does not imply endorsement. Items do not represent the official views of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or of Book of Mormon Central.