KnoWhy #811 | September 2, 2025

Why Were the Latter-day Saints Driven Out of Jackson County, Missouri?

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

“Therefore, they must needs be chastened and tried, even as Abraham, who was commanded to offer up his only son. For all those who will not endure chastening, but deny me, cannot be sanctified.” Doctrine and Covenants 101:4–5

The Know

From 1831 to 1833, many Latter-day Saints lived in Jackson County, Missouri. Many of these Saints lived in Independence, the county seat, after the Lord had declared that Independence was “the center place” and “the place for the city of Zion” (Doctrine and Covenants 57:2–3). During the two years the Church had a presence in Jackson County, however, the leaders there often had heated disagreements with Joseph Smith and other leaders still in Kirtland. As Grant Underwood observed, “Petty arguments had occurred off and on from the fall of 1831 to the summer of 1833. Surviving letters show they were trying to work through their disagreements, but a lack of full harmony among the leadership seemed to persist.”1

During these two years, the Lord had constantly warned the Saints in Missouri that they must remain humble. On March 18, 1833, the Lord stated that if Church leaders and members in Zion would not repent and strive to follow all of the commandments they had been given, “I, the Lord, will contend with Zion, and plead with her strong ones, and chasten her until she overcomes and is clean before me.”2 In the few months following this revelation, the leaders in Jackson County resolved their differences with Joseph again and were working closely with him to make plans for the city of Zion and the temple. “However,” Brent M. Rogers notes, “a multi-faceted conflict between the [Latter-day Saints] and their neighbors deterred . . . plans to build the city of Zion.”3 This conflict, instigated by the non-member residents of Jackson County, would ultimately conclude with all the Latter-day Saints being forcibly driven from their homes and the county.

The conflict between those Missourians and the Latter-day Saints, Andrew H. Hedges notes, “was rooted in a variety of factors. Perhaps most fundamental was the ideology between the two groups.”4 As with many similar disputes that arose in the early history of the United States and especially in the early years of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ideological conflicts were especially rooted in the political landscape of the day. Missouri had gained statehood in 1821, just a decade before Latter-day Saints first arrived in Independence. Its path to statehood had been rocky, as debates regarding slavery dominated the United States: the southern states accepted the practice of slavery, but the other half outlawed it and also sought to limit its spread into new states and territories acquired by the country.

Eventually, Missouri was accepted as a slave state through the Missouri Compromise of 1820, in which Maine was admitted as a free state at the same time keeping the balance between free and slave states even. As the population in Missouri grew, most of the state’s “early settlers were southerners, and her political and economic sensibilities were clearly oriented toward the South both before and after obtaining statehood.”5 Missouri was also the westernmost state in the country at this time, making Jackson County “the frontier of the United States in the early 1830s.”6 Thus, it had become not only the outfitting head of the Santa Fe Trail heading west and into Mexico but also “a rendezvous for fugitives from justice in the states” back in the east. This led one Christian evangelist to earlier remark how Jackson County was a “godless place, filled with so many profane swearers . . . [who] make a mild profession of Christian religion, but it is mere words, not manifested in Christian living.”7

The Latter-day Saints, on the other hand, came “largely from the anti-slavery Northeast and Puritan New England and [were] looking for a place to raise families and worship their God.” 8 Furthermore, even though the Saints had been commanded to wait for an appointment to move to Zion so as to not overwhelm the limited resources available to the bishop or to the Saints, many moved there without that appointment from the Lord.9 This influx led Missourians to worry that the Latter-day Saints would soon become a political majority capable of controlling local affairs, and they even feared being driven out of their lands.10

As President Dallin H. Oaks and Marvin S. Hill noted, “Although the [Latter-day Saints] did not become involved in local politics during their first year [in Independence in Jackson County], many Missourians [there] feared that the immigrants would soon monopolize political offices. As Mormons occupied public lands, the old settlers perceived them as economic rivals.”11 Their fears only increased when William W. Phelps, in Missouri, published an article in the July issue of the new Church periodical The Evening and Morning Star that cautioned Black converts from settling in Independence because it was a slave state.12 This article was wildly misconstrued, and even though “relatively few Jackson County citizens owned slaves,” people there falsely claimed the Latter-day Saints were attempting to instigate a slave rebellion.13

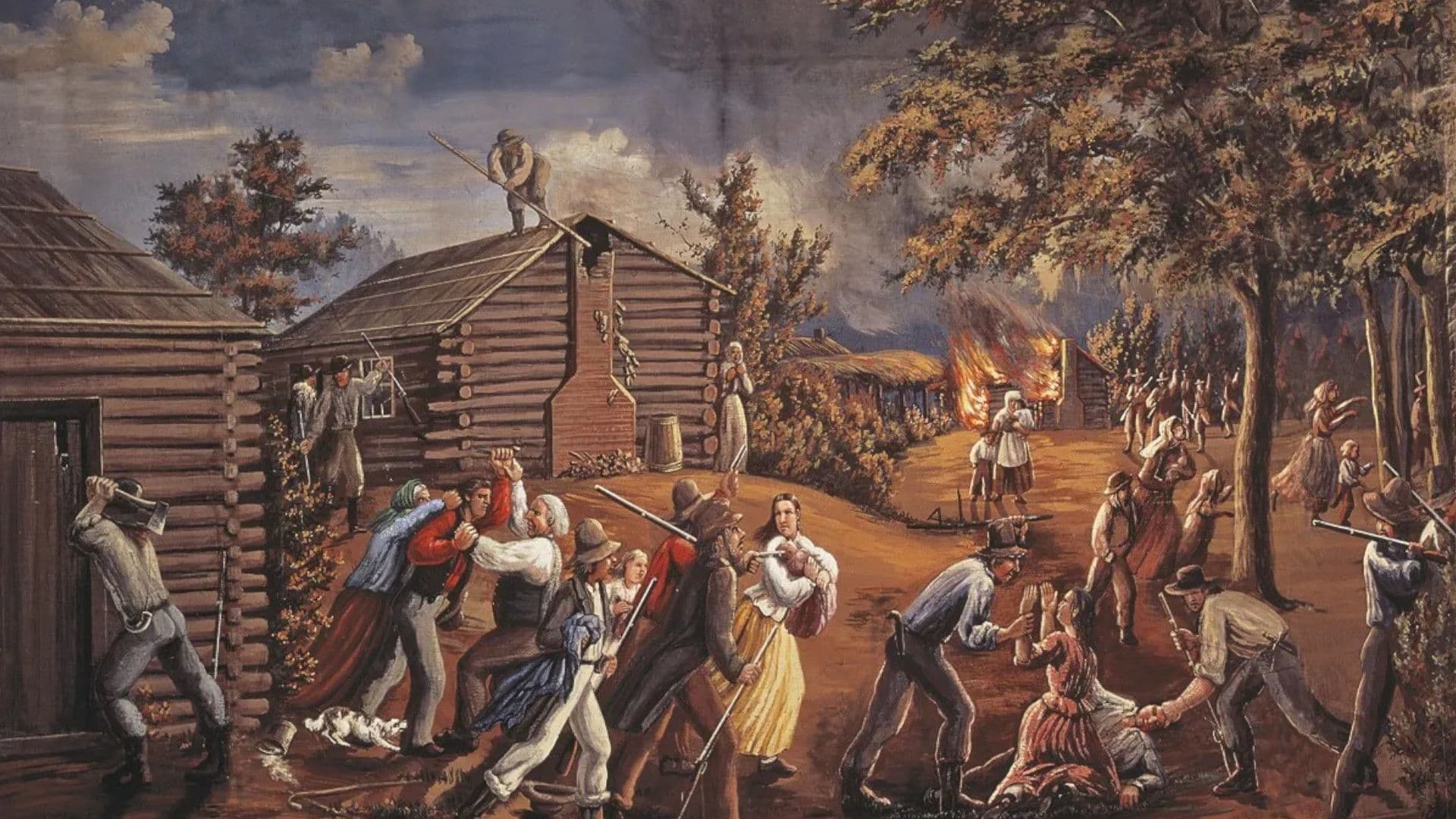

Action from the incensed Missouri mob came quickly. They drew up a manifesto demanding (1) that no additional Latter-day Saints be allowed to move into Jackson County, (2) that those Latter-day Saints already in Jackson County sell their property and move elsewhere, (3) that the Evening and Morning Star cease all its publications, and (4) that all stores owned by Latter-day Saints close.14 Bishop Edward Partridge was given only fifteen minutes to consider and agree to these demands. When he did not, the mob burned William W. Phelps’s press down and tarred and feathered Partridge and Charles Allen.15 After forcing the Church leaders to sign an agreement that all the Saints would leave Jackson County in 1834, the mob became further angered when they learned that some of the Saints began seeking legal representation in order to maintain title to their lands and to assert protections under their constitutional rights. As a result, their homes were destroyed and innocent people were whipped and beaten, and all the faithful Saints were forcibly driven from the county in the dead of the winter of 1833.16

The Why

In August 1833 when Joseph Smith heard about the extreme persecutions that the Saints were suffering, he sought to comfort and reassure the Saints. In a revelation given on August 6, 1833, back in Ohio, the Lord stated, “He giveth this promise unto you, with an immutable covenant that they shall be fulfilled; and all things wherewith you have been afflicted shall work together for your good, and to my name’s glory, saith the Lord” (Doctrine and Covenants 98:3). This echoed a previous promise the Lord had made in August 1831:

Ye cannot behold with your natural eyes, for the present time, the design of your God concerning those things which shall come hereafter, and the glory which shall follow after much tribulation. For after much tribulation come the blessings. Wherefore the day cometh that ye shall be crowned with much glory; the hour is not yet, but is nigh at hand.” (Doctrine and Covenants 58:3–4)

In another revelation received on December 16–17, 1833, the Lord also stated that much of this persecution had occurred due to transgressions of some of the Saints in Independence. This persecution was not meant to revoke the blessings of Zion, however. Rather, “they must needs be chastened and tried, even as Abraham, who was commanded to offer up his only son. For all those who will not endure chastening, but deny me, cannot be sanctified” (Doctrine and Covenants 101:4–5). Through these trials, the faithful Saints would indeed deeply learn to rely on God so that they could become more like Him.17

Although these trials in Missouri were, unfortunately, just beginning in 1833, many of the Latter-day Saints who found themselves in the refiner’s fire of Missouri came out firmer in their faith.18 Even as they were driven from the state of Missouri five years following, the body of the Saints took comfort in the promise that “all they who have mourned shall be comforted. And all they who have given their lives for my name shall be crowned. Therefore, let your hearts be comforted concerning Zion; for all flesh is in mine hands; be still and know that I am God. Zion shall not be moved out of her place, notwithstanding her children are scattered” (Doctrine and Covenants 101:14–17).

Similarly, when modern Latter-day Saints experience personal trials of their own, they can likewise find comfort in the promises God has made to His children, trusting that all the trials they suffer will eventually be sanctified to work together for their good.

“Jackson County Violence,” Church History Topics, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Clark V. Johnson and Leland H. Gentry, “Missouri,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (Macmillan, 1992), 922–27.

Max H. Parkin, “Missouri Conflict,” in Ludlow, Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 927–32.

Brent M. Rogers, “Prelude to the March: The Expulsion from Zion and Plans for Redemption,” in Zion’s Camp, 1834: March of Faith, ed. Matthew C. Godfrey (History of the Saints, 2018), 5–31.

Grant Underwood, “Expulsion from Zion,” in Joseph Smith, the Prophet and Seer, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Kent P. Jackson (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Deseret Book, 2010), 138–50.

Andrew H. Hedges, “Mobocracy in Jackson County,” in Joseph: Exploring the Life and Ministry of the Prophet, ed. Susan Easton Black and Andrew C. Skinner (Deseret Book, 2005), 207–17.

T. Edgar Lyons, “Independence, Missouri, and the Mormons, 1827–1833,” BYU Studies 13, no. 1 (1972): 10–19.

- 1. Grant Underwood, “Expulsion from Zion,” in Joseph Smith, the Prophet and Seer, ed. Richard Neitzel Holzapfel and Kent P. Jackson (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Deseret Book, 2010), 138.

- 2. Doctrine and Covenants 90:36. Joseph Smith would reiterate these warnings in his own letters to the Saints in Zion, warning them that their antagonistic spirit was “wasting the strength of Zion like a pestilence, and if it is not detected and driven from you it will ripen Zion for the threatened judgments of God.” “Letter to William W. Phelps, 11 January 1833,” p. 18–19, The Joseph Smith Papers; spelling and punctuation silently modernized.

- 3. Brent M. Rogers, “Prelude to the March: The Expulsion from Zion and Plans for Redemption,” in Zion’s Camp, 1834: March of Faith, ed. Matthew C. Godfrey (History of the Saints, 2018), 7.

- 4. Andrew H. Hedges, “Mobocracy in Jackson County,” in Joseph: Exploring the Life and Ministry of the Prophet, ed. Susan Easton Black and Andrew C. Skinner (Deseret Book, 2005), 207.

- 5.

- 6. Hedges, “Mobocracy in Jackson County,” 207; emphasis in original.

- 7. T. Edgar Lyons, “Independence, Missouri, and the Mormons, 1827–1833,” BYU Studies 13, no. 1 (1972): 15–16.

- 8. Hedges, “Mobocracy in Jackson County,” 208.

- 9. See Doctrine and Covenants 58:56; Hedges, “Mobocracy in Jackson County,” 209.

- 10. While Doctrine and Covenants 45:72 directly forbade the Saints from doing any such thing, many Missourians took the idea that Independence was to be Zion out of context, driving fears that the Saints would forcibly remove Missourians from their homes. See Hedges, “Mobocracy in Jackson County,” 208–10; Rogers, “Prelude to the March,” 7–8, 10.

- 11. Dallin H. Oaks and Marvin S. Hill, Carthage Conspiracy: The Trial of the Accused Assassins of Joseph Smith (University of Illinois Press, 1975), 8.

- 12. Underwood, “Expulsion from Zion,” 139; Oaks and Hill, Carthage Conspiracy, 8; Rogers, “Prelude to the March,” 11.

- 13. See Underwood, “Expulsion from Zion,” 139; Rogers, “Prelude to the March,” 11.

- 14. Lyons, “Independence, Missouri, and the Mormons,” 18.

- 15. Rogers, “Prelude to the March,” 12; Underwood, “Expulsion from Zion,” 139.

- 16. Rogers, “Prelude to the March,” 13–17; Lyons, “Independence, Missouri, and the Mormons,” 18–19.

- 17. For additional context on these revelations, see David W. Grua, “Waiting for the Word of the Lord: D&C 97, 98, 101,” in Revelations in Context: The Stories Behind the Sections of the Doctrine and Covenants, ed. Matthew McBride and James Goldberg (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2016), 196–201.

- 18. For a discussion of the later expulsion of the Latter-day Saints from the state of Missouri in 1838–39, see Scripture Central, “Why Were the Saints Driven from Missouri in the Fall of 1838? (Doctrine and Covenants 121:6),” KnoWhy 620 (February 17, 2023).