KnoWhy #762 | November 12, 2024

Why Was the Brother of Jared’s Name Not Included in the Book of Ether?

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

“And the brother of Jared being a large and mighty man, and a man highly favored of the Lord, Jared, his brother, said unto him: Cry unto the Lord, that he will not confound us that we may not understand our words.” Ether 1:34

The Know

Joseph Smith identified the name of the brother of Jared as Moriancumer (or Mahonri Moriancumer), but the man is unnamed in the Book of Ether as Moroni abridged it.1 A variety of reasons have been proposed to explain this, including that the name was lost, that the book emphasized Jared’s lineage, or that problems in translation occurred.2 Most recently, Walker Wright suggests that the absence of the brother of Jared’s name has to do with the biblical background of Jared and his brother—particularly the story of the Tower of Babel and early aspects of the book of Genesis.3

Wright suggests that the brother of Jared remains nameless as a deliberate contrast from the people trying to “make a name” for themselves by building the tower of Babel (Genesis 11:4). Throughout the early chapters of Ether, other subtle contrasts between the people of Jared and the people of Babel help support this conclusion.4 Furthermore, contrasting the brother of Jared with a wicked people would accord well with contrasts recorded in the Bible between Israel and their wicked neighbors.5

Genesis reports details of the wicked society that the brother of Jared left. Genesis 6 mentions that before the Flood, illicit marriages were taking place outside the covenant between the “sons of God” and “daughters of men.” The children of these unions are called “giants,” “mighty men,” and “men of renown,” which in Hebrew is literally “men of name.”6 These people’s wickedness was temporarily washed away by the Flood, but their legacy of seeking renown seemed to be revived afterwards.7 One of the more significant individuals that both Genesis and Ether mention is Nimrod, a king, hunter, and “mighty one.”8 Though he is said to be “before the Lord,” most traditions actually considered him to be a wicked man, similar to the pre-Flood “mighty men” to whom he has been compared.9

Nimrod’s people in the land of Shinar certainly also maintained the concern with renown that the earlier “mighty men” had. The people of Babel said, “Let us build us a city and a tower, whose top may reach unto heaven; and let us make us a name, lest we be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth” (Genesis 11:4; emphasis added). The Lord responded by confounding the language of the people of Babel, which halted their construction project, and then He scattered them from that location (Genesis 11:5–9).

Wright suggests that each of the three goals of Nimrod’s people at Babel—resisting scattering and dispersion, making a name for themselves, and improperly entering into the presence of God—is a sin with which the brother of Jared and his people deliberately contrast in desire and method.10 Knowing these goals can help elucidate several details of the brother of Jared narrative in Ether.

Resisting Scattering and Dispersion

One of the reasons explicitly listed in scripture why Nimrod’s people built their tower and tried to make a name is so that they would not be scattered (Genesis 11:4). Scripture suggests that scattering is typically a divine punishment, so the desire not to be scattered was not inherently inappropriate. In this instance, it may have been wrong because it defied God’s pressing command to spread forth and replenish the earth. Josephus, a later Jewish historian, suggested that the people of Babel thought construction technology could make them immune to punishments from God like Noah’s Flood, therefore trusting in the arm of flesh rather than in God.11

Jared and his brother had no such fear of dispersion, or at least it was outweighed by a desire to be led by God and avoid the punishments coming upon Babel. Wright notes, “The brother of Jared and his company also did not resist the Lord’s command to fill the earth and allowed him to ‘drive [them] out of the land’ to ‘a land which is choice above all the earth’ (Ether 1:38). . . . Instead of being part of the name-hungry, disobedient, and forcibly scattered people of Babel, the Jaredite origins are rooted in the humility and experiences of an unnamed man.”12

Making a Name

One goal of Nimrod’s society at Babel and of the “men of name” who preceded them was to “make a name” for themselves and to achieve renown for their might. This could be done through demonstrations of power like the construction of the Tower of Babel. Renown seems to also be connected to the idea of not being scattered: a sufficiently large empire, with its harsh monarchy, was probably thought to be invincible and immune to God’s judgment.13

The brother of Jared, by contrast, remains nameless but is made renowned by the Lord; his vision of all things will be revealed to the world at some future time (Ether 4). Rather than wanting to build up a legendary kingdom among his own people, the brother of Jared rejected power and urged his people not to appoint a king. Perhaps based on what he had learned from Babel’s wicked kings, he could testify, “Surely this thing leadeth into captivity” (Ether 6:23).

Improperly Entering God’s Presence

Biblical scholars generally agree that the so-called Tower of Babel was a Mesopotamian ziggurat, an artificial mountain that served as a temple to connect heaven and earth.14 Many ziggurats were built in Mesopotamia for a specific deity, so perhaps idolatrous worship was one of Babel’s sins.15 Some have also suggested that seeking to make a name could have been a corrupt form of temple worship, either in worshipping a false deity or in rebelling against Jehovah.16

Nimrod is described in Genesis 10:9 as being “before the Lord,” though the Joseph Smith Translation replaces this with “in the land” and Jewish, Islamic, and Christian traditions see Nimrod as being wicked.17 The phrase “before the Lord” is often understood in a temple context in the Old Testament. Thus, there is a level of irony in Nimrod attempting to gain God’s presence forcibly with his temple-tower.18

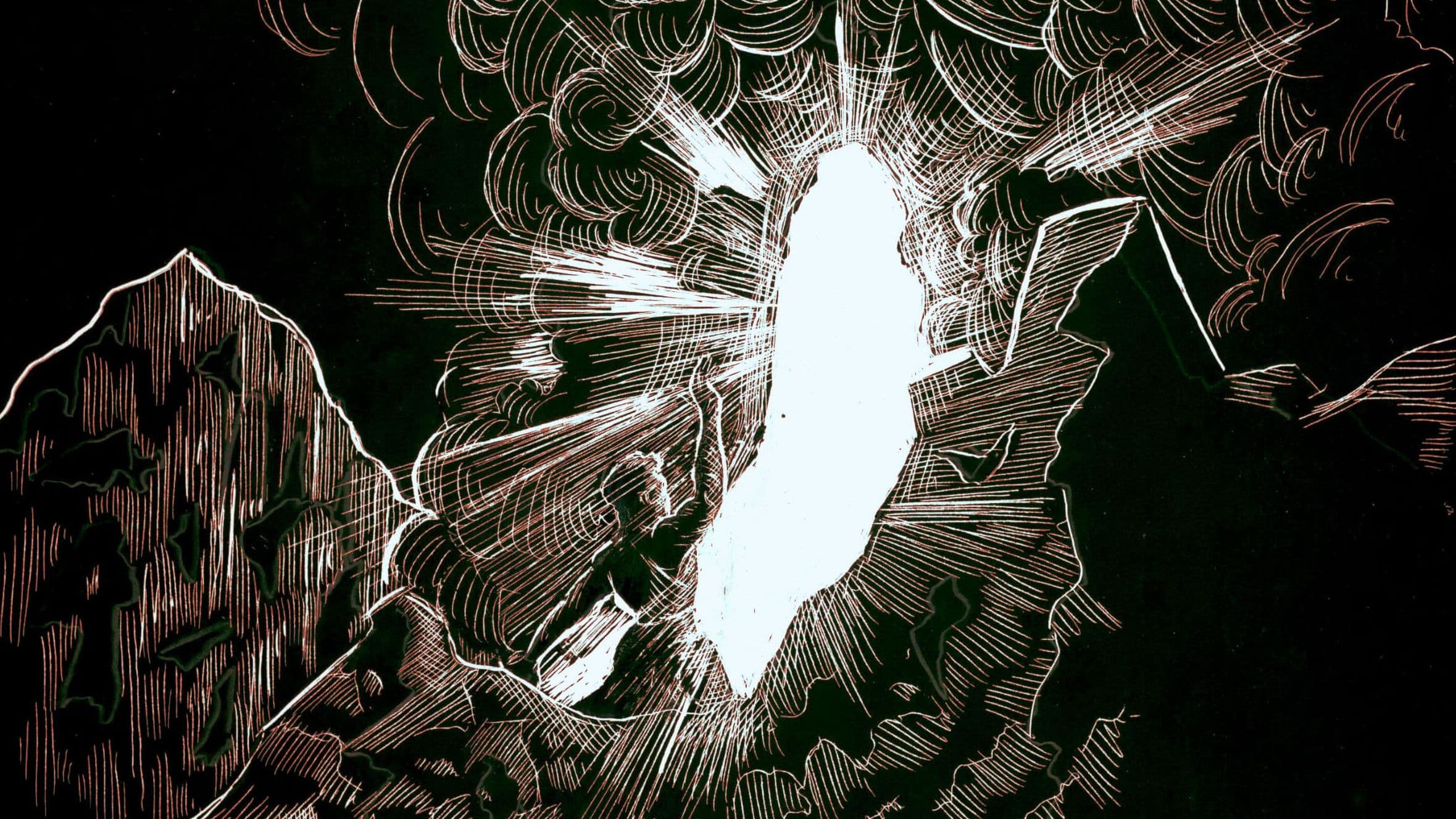

In contrast to the wicked King Nimrod, the brother of Jared was able to literally enter God’s presence.19 Thus, it makes sense that the brother of Jared is described as being before the Lord repeatedly and in his temple-like experiences on Mount Shelem, a natural temple that stands in stark contrast to the idolatrous temple-tower of Babel.20 There, the premortal Jesus appeared to the brother of Jared and showed him a vision of all things.21 In fact, to some extent his entry into God’s presence was a surprise intrusion, leading Elder Jeffrey R. Holland to call the brother of Jared “not . . . an unwelcome guest but perhaps technically an uninvited one.”22 The brother of Jared’s strong faith therefore contrasts with the prideful attempted intrusion of Nimrod into the sky. Or, as Wright observed, “In essence, the brother of Jared is shown to be everything Nimrod failed to be; the anti-Nimrod.”23

The Why

It is not wrong in principle to desire to gather with others, build cities, build temples, receive a name, and ultimately enter God’s presence. Righteous Jaredites, Nephites, and Latter-day Saints have done so, and Joseph Smith suggested that such is the whole purpose of the gathering of Israel.24 While these desires can be righteous, they must never keep us from obeying God’s commandments. Failure to keep those commandments will only serve to alienate us, like the people of Babel, from God. Furthermore, desiring to approach God solely to gain renown and power is an unrighteous desire that brought upon Babel the punishments of God.

God is the most powerful being in the universe and enjoys incomparable power, glory, and renown, residing in the heavens and overseeing the affairs of humankind. Enjoying such power and glory cannot be achieved if one appeals to “the nature and disposition of almost all men” because “as soon as they get a little authority, as they suppose, they will immediately begin to exercise unrighteous dominion” (Doctrine and Covenants 121:39). Scripture informs us that Satan proposed his malicious plan in the premortal realm because he desired God’s honor and glory for himself, setting the ultimate example of who not to follow.25

In contrast, the scriptures suggest that the power that God enjoys and exercises is strictly attached to His perfect virtue (D&C 121:41–42). In fact, it is achieved paradoxically by shunning it. Jesus, who received all power, descended below all things; He taught us that the greatest among us is our servant (Matthew 20:25–28). All people are to emulate God’s virtue rather than unrighteously imitate His power. By bringing ourselves down into the depths of humility, as the brother of Jared did, we can experience the fullest blessings of the Lord because then he will “come down” to us (Ether 2:4). Indeed, as Matthew L. Bowen has observed, “Moroni seems to have made an ongoing narrative effort to associate the name Jared [whose name means ‘to go down; descend’] with the Lord’s theophanic ‘condescensions’ or ‘coming[s] down’ and the origin of the Jaredites as a people.”26

Thus, the comparison of the brother of Jared with the people of Babel can reinforce how little pride and reputation matter. Though many of the Saints in scripture and history remain nameless in our time, we are reassured that the faithful and their deeds are all recorded in the book of life and will be remembered and lauded forever. We can follow Jesus’s teaching that those who “have glory of men . . . have their reward. But . . . let not thy left hand know what thy right hand doeth: that thine alms may be in secret: and thy Father which seeth in secret himself shall reward thee openly.”27

Walker Wright, “The Man with No Name: The Brother of Jared as an Anti-Babel Polemic,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 62 (2024): 319–333.

Matthew L. Bowen, “Coming Down and Bringing Down: Pejorative Onomastic Allusions to the Jaredites in Helaman 6:25, 6:38, and Ether 2:11,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 42 (2021): 397–410.

Jeffrey M. Bradshaw and David J. Larsen, In God’s Image and Likeness 2: Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel (Eborn Books; Interpreter Foundation, 2014), 379–439.

- 1. The name Moriancumer appears as a place name in Ether but not as the name of the brother of Jared (Ether 2:13). The name of the brother of Jared was noted to be Moriancumer in an 1835 letter by Oliver Cowdery. See Oliver Cowdery, “Letter VI. To W. W. Phelps, Esq.,” Messenger and Advocate, April 1835, 112; reprinted as “Rise of the Church: Letter VI,” Times and Seasons, April 1, 1841, 362. However, in 1834 Joseph Smith had blessed a baby and gave it the name Mahonri Moriancumer Cahoon, and a publication by George Reynolds almost sixty years later in 1892 asserted that Joseph Smith had revealed it as the full name of the brother of Jared. Mahonri Moriancumer Cahoon died four years before the publication (in 1888), but Reynolds claimed Mahonri’s still-living brother William F. Cahoon as a source for the knowledge. George Reynolds, “The Jaredites,” Juvenile Instructor, May 1892, 282. Rex C. Reeve Jr., “The Brother of Jared,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow, 4 vols. (Macmillan, 1992), 1:235–236.

- 2. Daniel H. Ludlow, A Companion to Your Study of the Book of Mormon (Deseret Book, 1976), 310; Brant Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 6 vols. (Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 6:166.

- 3. Walker Wright, “The Man with No Name: The Brother of Jared as an Anti-Babel Polemic,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 62 (2024): 319–333. For another comparison between the brother of Jared story and biblical traditions about Jonah, see Scripture Central, “How Were Jonah and the Brother of Jared Able to Find Comfort? (Ether 3:2),” KnoWhy 256 (August 2, 2019).

- 4. Wright, “Man with No Name,” 320, postulates, “The opening of the book of Ether could be seen as a polemic against Babel and its leader, with Moroni’s telling of the brother of Jared story serving as the main contrast.” A table containing a list of comparisons between the brother of Jared and the people of Babel can be found on pp. 323–324 of Wright’s article.

- 5. Scholars have long noted how aspects of the Old Testament appear to be written as a deliberate argument or polemic against Israel’s neighbors. This can be seen, for example, in the Creation account in Genesis 1, which shows the superiority of God to neighboring cultures’ idols. For a treatment of how the Old Testament narrative compares with and argues against those from neighboring cultures, see John D. Currid, Against the Gods: The Polemical Theology of the Old Testament (Crossway, 2013); Gerhard F. Hasel, “The Polemic Nature of the Genesis Cosmology,” Evangelical Quarterly 45, no. 2 (1974): 81–102. Wright, “Man with No Name,” 319–322, specifically notes the Creation narrative, the Joseph story, and the plagues of Egypt as biblical polemics, with additional potential polemics found in the book of Abraham. For a discussion on how the plagues of Egypt may have been sent in response to Egyptian beliefs, see Scripture Central, “Why Were Particular Plagues Sent Against Egypt? (Exodus 7:3, 5),” KnoWhy 631 (March 31, 2022).

- 6. Genesis 6:1–5. A common interpretation of these verses, popular in early Judaism, was that the giants (nephilim) were the children of angelic men (sons of God) and mortal women whose giant children had supernatural abilities. However, in Moses 8:13–21 and some other ancient commentaries, the marriages are considered to be outside of the covenant instead of with supernatural beings, and the children of these marriages are not directly connected with giants. See Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, In God's Image and Likeness 1: Creation, Fall, and the Story of Adam and Eve (Eborn Books, 2014), 585–590; Ludwig Koehler, Walter Baumgartner, and Johann J. Stamm, The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament [HALOT], ed. Mervyn E. J. Richardson, 2 vols. (Brill, 2001), s.v. “נְפִילִים.” The phrase “men of name” is also translated in the King James Version as “men of renown” in Numbers 16:2 but as “famous men” in 1 Chronicles 5:24. See Koehler, Baumgartner, and Stamm, HALOT, s.v. “שֵׁם.”

- 7. Righteous traditions also survived the Flood that appear to be at play in the early chapters of Ether. One possibility is that the brother of Jared’s shining stones were an imitation of a similar stone used by Noah. See Scripture Central, “Where Did the Brother of Jared Get the Idea of Shining Stones? (Ether 6:3),” KnoWhy 240 (August 21, 2019).

- 8. Genesis 10:8–10; Ether 2:1. Some have equated Nimrod with either Sargon or Naram-Sin, the Akkadian kings who built the first known empire in the region circa 2200 BCE. Others equate him with later Babylonian kings like Sulgi and Hammurabi. His status is somewhat legendary; some ancient authors considered him to be a giant, while some modern scholars have associated him with hunters among the Mesopotamian demigods and gods like Gilgamesh, Marduk, Nergal, or Ninurta. Bradshaw and Larsen, In God’s Image and Likeness 2: Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel (Eborn Books; Interpreter Foundation, 2014), 346–352; Yigal Levin, “Nimrod the Mighty, King of Kish, King of Sumer and Akkad,” Vetus Testamentum 52, no. 3 (2002): 350–366.

- 9. See Wright, “Man with No Name,” 325.

- 10. Wright, “Man with No Name,” 333, notes, “The people of Babel, led by the mighty hunter Nimrod, refused God’s command to multiply and fill the earth. Instead, they gathered together, built a high tower—a false temple—to reach the heavens, and sought to make a name or legacy for themselves. . . . The brother of Jared was a mighty, unnamed man who communed with the heavens on top of a high mountain. The language of his people was spared, and they spread across the face of the promised land. This is how Moroni’s abridgement of Ether presents the anti-Babel origins of the Jaredites.”

- 11. Bradshaw and Larsen, Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel, 394–396; Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, 1.114–115.

- 12. Wright, “Man with No Name,” 327. Matthew L. Bowen, “Coming Down and Bringing Down: Pejorative Onomastic Allusions to the Jaredites in Helaman 6:25, 6:38, and Ether 2:11,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 42 (2021): 401–403, also notes a wordplay between the name Jared, which means “to go down, descend,” and the instructions given by the Lord to “go . . . down” into the Valley of Nimrod, where the Lord himself “came down” to visit them, as recorded in Ether 1:41–2:4.

- 13. Bradshaw and Larsen, Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel, 394–396; Wright, “Man with No Name,” 329–330; F. Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, 1.114.

- 14. For a survey of potential options for the Tower of Babel, see Bradshaw and Larsen, Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel, 379–386.

- 15. Hugh Nibley, “What Is a Temple?,” in The Temple in Antiquity: Ancient Records and Modern Perspectives (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1984) 29, suggested the Tower of Babel was “the first pagan temple.” Josephus suggested that Nimrod was attempting to enter heaven to fight God, which may also support this view. Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, 1.114. Additionally, Joseph Smith taught on one occasion that Babel was actually in physical pursuit of the city of Zion in the sky. George Laub retrospectively reported that Joseph Smith taught, “Now I will tell the story of the designs of building the tower of Babel. It was designed to go to the city of Enoch for the veil was not yet so great that it hid it from their sight so they concluded to go to the city of Enoch. For God gave him place above the impure air for he could breath a pure air and him and his city was taken, for God provided a better place for him.” Bradshaw and Larsen, Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel, 396; Eugene England, “George Laub’s Nauvoo Journal,” BYU Studies 18, no. 2 (1978): 175.

- 16. Bradshaw and Larsen, Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel, 388–397.

- 17. Wright, “The Man with No Name,” 328–330; Kent P. Jackson, Joseph Smith’s Translation of the Bible: The Joseph Smith Translation and the King James Translation in Parallel Columns (Deseret Book; Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2021), 64.

- 18. Wright, “Man with No Name,” 328; Menahem Haran, Temples and Temple-Service in Ancient Israel: An Inquiry into Biblical Cult Phenomena and the Historical Setting of the Priestly School (Eisenbrauns, 1985), 26.

- 19. Ether 3:2, 6, 9, 13; 6:12. Though Shelem is said to be thus named because of its height, Walker cites scholarship suggesting that the name Shelem may be linked to the word for a peace offering performed in ancient temples and covenantal relationships. Wright, “Man with No Name,” 331–332; M. Catherine Thomas, “The Brother of Jared at the Veil,” in Temples in the Ancient World: Ritual and Symbolism, ed. Donald W. Parry (Deseret Book; Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies [FARMS], 1994), 390.

- 20. For a discussion on these contrasts, see Wright, “Man with No Name,” 331–332. On p. 332, Wright notes, “Mount Shelem is shown to be the true gateway to God. Once again, the brother of Jared and his people are shown to achieve where Babel failed—the anti-Babel.”

- 21. Scripture Central, “Why Did Moroni Use Temple Imagery while Telling the Brother of Jared Story? (Ether 3:20),” KnoWhy 237 (August 21, 2019); Scripture Central, “Why Did Jesus Say ‘Never Have I Showed Myself unto Man’? (Ether 3:15),” KnoWhy 584 (November 10, 2020).

- 22. Jeffrey R. Holland, “Rending the Veil of Unbelief,” in The Voice of My Servants: Apostolic Messages on Teaching, Learning, and Scripture, ed. Scott C. Esplin and Richard Neitzel Holzapfel (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Deseret Book, 2010), 157–158: “The brother of Jared, on the other hand, stands alone then (and we assume now) in having thrust himself through the veil, not as an unwelcome guest but perhaps technically an uninvited one. . . . We may ask here, ‘Could God have stopped the brother of Jared from seeing through the veil?’ At first blush one is inclined to say, ‘Surely God could block such an experience if He wished to.’ But think again. Or, more precisely, read again. ‘This man . . . could not be kept from beholding within the veil; . . . he could not be kept from within the veil’ (Ether 3:19–20; emphasis added).” Also see Jeffrey R. Holland, Christ and the New Covenant (Deseret Book, 1997), 13–29.

- 23. Wright, “Man with No Name,” 330.

- 24. “What was the object of gathering . . . the people of God in any age of the world? . . . The main object was to build unto the Lord a house whereby He could reveal unto His people the ordinances of His house and the glories of His kingdom, and teach the people the way of salvation; for there are certain ordinances and principles that, when they are taught and practiced, must be done in a place or a house built for that purpose. . . . It is for the same purpose that God gathers together His people in the last days, to build unto the Lord a house to prepare them for the ordinances and endowments, washings and anointings, etc.” “History, 1838–1856, volume D-1 [1 August 1842–1 July 1843],” p. 1572, The Joseph Smith Papers; Bradshaw and Larsen, Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel, 406.

- 25. Moses 4:1. Referring to the king of Babylon as Lucifer or a morning star, Isaiah also condemned this king for the same unrighteous desires of aspiring to godlike power in an inappropriate way—a condemnation that can be applied to the devil as well. Isaiah 14:12–15.

- 26. Bowen, “Coming Down and Bringing Down,” 402.

- 27. Matthew 6:2–4. Elder Uchtdorf spoke about this need to serve without concern for title or rank: “Individual recognition is rarely an indication of the value of our service. We do not know the names, for example, of any of the 2,000 sons of Helaman. As individuals, they are unnamed. As a group, however, their name will always be remembered for honesty, courage, and the willingness to serve. They accomplished together what none of them could have accomplished alone. . . . When we stand close together and lift where we stand, when we care more for the glory of the kingdom of God than for our own prestige or pleasure, we can accomplish so much more.” Dieter F. Uchtdorf, “Lift Where You Stand,” October 2008 general conference.