KnoWhy #737 | June 25, 2024

What Materials and Formats Were Used by Nephite Record Keepers?

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

And now there are many records kept of the proceedings of this people, by many of this people, which are particular and very large. … But behold, there are many books and many records of every kind, and they have been kept chiefly by the Nephites. Helaman 3:13, 15

The Know

The Book of Mormon frequently mentions various records kept by Nephite historians and prophets.1 In many cases, these records were made on metal plates.2 In addition to metals, a wide variety of writing materials were used in the ancient world, including stone, clay tablets, pottery shards, wooden and ivory tablets, papyrus, and parchment.3 The Nephites almost certainly used many of these different kinds of writing materials, some of which would have been perishable materials for making copies for more regular use among the population. A hint of this is found in the account of Alma and Amulek’s preaching at Ammonihah, when wicked men executed believers by fire and then “brought forth their records which contained the holy scriptures, and cast them into the fire also, that they might be burned and destroyed by fire.”4

Modern readers may naturally assume that all these records were in book form, or what scholars call a codex—that is, a series of leaves or pages bound together on one side—since that is the format most common today. Indeed, the codex form is consistent with the form of Mormon’s final record, as described by Joseph Smith and the witnesses who saw and handled it.5 Yet in the ancient world, a book-length document could take a variety of forms, and each form could be made using metal or more perishable materials.

Scroll

The most common format for lengthy documents, at least in the ancient Near East during the early first millennium BC, was a scroll, usually of papyrus or sometimes parchment. This format goes back to at least 3000 BC.6 Scrolls could also be made of metal, as attested by the Copper Scroll found among the Dead Sea Scrolls, which is made of multiple copper plates riveted together and rolled up into a scroll.7 A small pair of inscribed silver scrolls were found in Jerusalem dating right to Lehi’s time, illustrating that metal scrolls existed in Lehi’s day.8

Codex

The traditional codex (plural, codices) form may have also been in use in Lehi’s day. This is the type of book that many readers today would think of, with a series of leaves bound together on one side.9 Some codices were made of metal plates in the Roman Empire, which issued hundreds of thousands of military diplomas each engraved on a set of two bronze plates bound together by two rings to make a four-page codex.10 In ancient and medieval India, many sets of lengthy texts engraved on large copper plates have been found bound together variously by one or two rings.11 The Book of Mormon’s binding is similar to these ancient examples, except it had three D-shaped rings, which has proven to be a more optimal binding format for such a lengthy text.12

The scholarly consensus long held that the codex was not invented until the first or second century AD, but a recent discovery illustrates that codices were in use in Egypt as early as the third century BC. “A 10-by-6-inch piece of papyrus is, researchers now believe, part of the world’s first [known] book. The papyrus fragment … began as a bound document dating to 260 BC.”13 This makes the possibility that the plates of brass—which may have had a connection to Egyptian literary practices (Mosiah 1:3–4)—were bound in a codex format in the first millennium BC significantly more plausible.

Writing Boards and the Screenfold Codex

Long compositions could also be written on series of wooden or ivory writing tablets that were then hinged together so that they could be unfolded accordion style.14 Examples of two or three boards hinged together are well attested throughout the ancient Near East in the early first millennium BC, and “fairly long compositions could be accommodated by hinging together a number of individual boards.”15 In the sixth or seventh century AD, this format was used with gold plates in Korea, where lengthy texts consisting of fourteen to nineteen leaves bound together by hinges in an accordion style.16

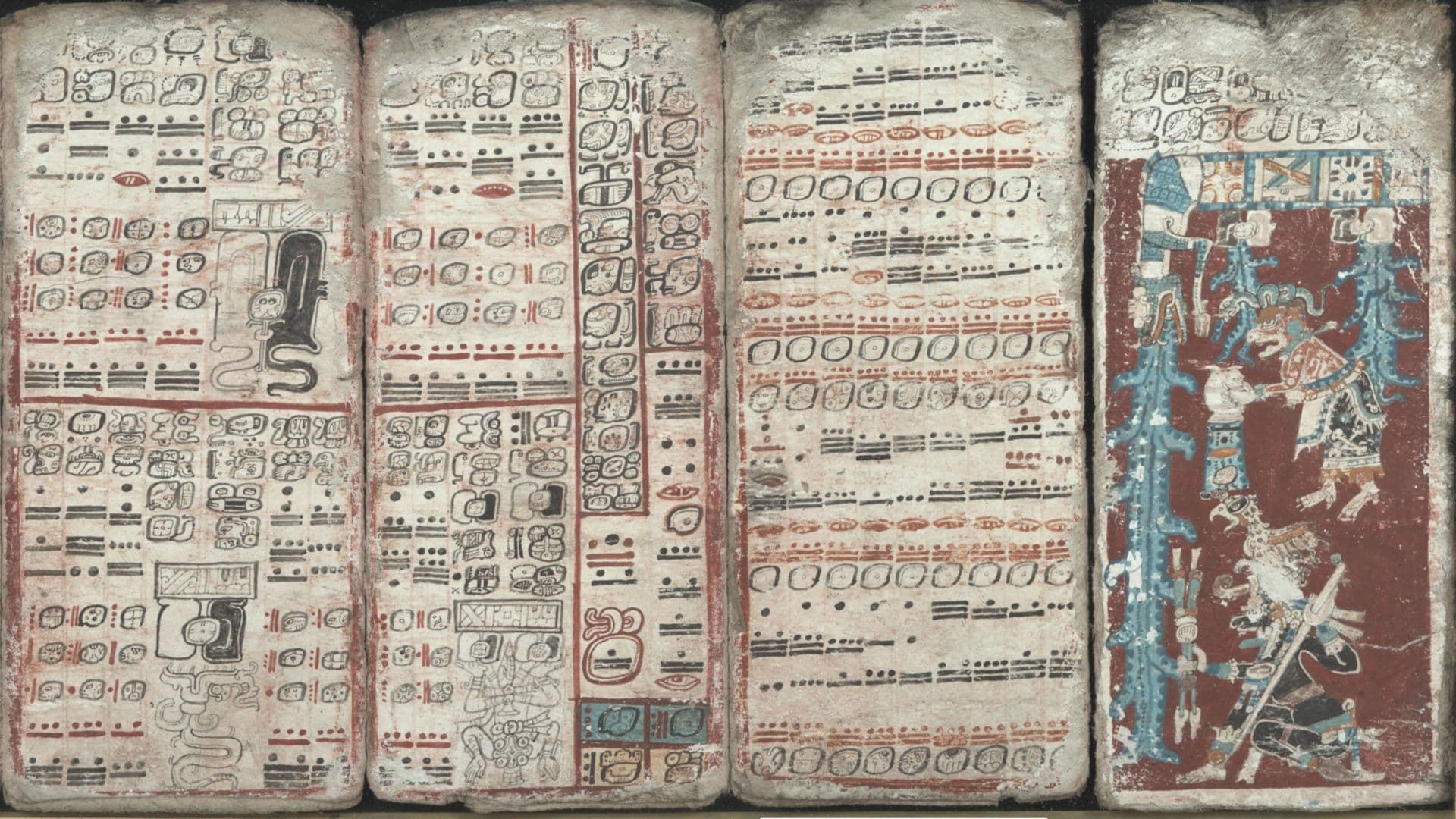

A very similar format was used for books in ancient Mesoamerica using bark paper. John L. Sorenson explained, “Screenfold books were the most common form of document.” They were typically made “from the bark of a type of fig tree” that was soaked and pounded into paper, then coated with a lime plaster to “make a smooth, clean surface on which characters were painted. The strips were [then] folded back and forth accordion fashion to pile up ‘pages.’”17

Only four such Maya codices survive today, all from the post-Classic period (ca. AD 900–1500).18 Yet Maya artwork on ceramics illustrates that screenfold codices were being made during the Classic period (ca. AD 300–900).19 Fragments of such codices were recovered at two archaeological sites from an early Classic context—at Uaxactun, dated to AD 400–600, and at Mirador (in Chiapas, Mexico), dated to AD 350–550.20 Despite the scant evidence, Michael D. Coe reasoned, “There must have been thousands of such books in Classic times.”21 Illustrations of “two objects which appear to be side views of codices, each bound with a ribbon or cord” on an Olmec-style ceramic bowl indicate that “the screenfold codex made from amate bark … may already have been present in Mesoamerican culture as early as 1200 BC.”22

One of the reasons so few pre-Columbian Maya books survive is that the Spanish friars burned many of the Maya and Aztec codices they found, similar to the burning of records at Ammonihah in the Book of Mormon.23 Since ancient American screenfold books made of bark paper appear to go back to Book of Mormon times, it seems likely that these would have been the kinds of documents the people of Ammonihah destroyed. Interestingly, Alma had earlier told the people of Ammonihah that he would “unfold the scriptures beyond that which Amulek had done” (Alma 12:1), a figure of speech that applies especially well to screenfold codices, which literally had to be unfolded to be read.24

The Why

It is clear that the Nephites could have employed a variety of materials and formats as they kept “many books and many records of every kind” (Helaman 3:15). Understanding what record keeping options were available to the Nephites may seem like a minor point, but it can help modern readers better visualize the Nephite record repository Mormon had at his disposal, deepening their appreciation for how “the creation of the Book of Mormon was a complicated business” of sifting through vast records of every kind.25

Familiarity with the different kinds of record-keeping formats can also help put into context the way the Book of Mormon plates were bound together and why that format was chosen over others. While metal plates could be formed into a scroll, this format was not very space efficient and thus would not have been effective for such a lengthy record; likewise, a screenfold-style metal codex the length of the Book of Mormon would have been unwieldy to unfold. The standard codex format was the most practical option for a record of this size, and the use of three D-shaped rings optimized this format better than other ancient examples of codex-like metal documents.

Similarly, knowing more about the perishable materials at the Nephites’ disposal for record keeping can also help modern readers better appreciate why metal plates became the preferred option for their most important records that they needed to last.26 Very early on, Nephite record keepers came to understand that “whatsoever things we write upon anything save it be upon plates must perish and vanish away” (Jacob 4:2). Indeed, the scant survival of New World codices corroborates this reality.27 Inscribing on stone was also possible but would not have been sufficiently compact or portable for keeping and preserving extensive records.28

All this can deepen readers’ appreciation of the monumental effort made by Nephite scribes as they “labor[ed] diligently to engraven these words upon plates, hoping that our beloved brethren and our children will receive them with thankful hearts, and look upon them that they may learn with joy … that we knew of Christ, and we had a hope of his glory many hundred years before his coming” (Jacob 4:3–4).

Brant A. Gardner, Labor Diligently to Write: The Ancient Making of a Modern Scripture, Interpreter 35 (Orem, UT: The Interpreter Foundation, 2020), 13–22.

John W. Welch, “Doubled, Sealed, Witnessed Documents: From the Ancient World to the Book of Mormon,” in Mormons, Scripture, and the Ancient World: Studies in Honor of John L. Sorenson, ed. Davis Bitton (Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies [FARMS], 1998), 391–444.

John L. Sorenson, “The Book of Mormon as a Mesoamerican Record,” in Book of Mormon Authorship Revisited: The Evidence for Ancient Origins, ed. Noel B. Reynolds (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1997), 391–521.

John L. Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex: An Ancient American Book (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2013), 187–232.

- 1. See Helaman 3:13, 15. See also the discussion in Brant A. Gardner, Labor Diligently to Write: The Ancient Making a Modern Scripture, Interpreter 35 (Orem, UT: The Interpreter Foundation, 2020), 13–22; John L. Sorenson, “Mormon’s Sources,” Journal of Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 20, no. 2 (2011): 2–15; John L. Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex: An Ancient American Book (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2013), 187–218.

- 2. Records on metal plates include the plates of brass (1 Nephi 5:10–19; Alma 37:3–5), the large and small plates of Nephi (1 Nephi 6:1; 9:2–4; 19:1–7; 2 Nephi 5:30–32; Jacob 1:1–4; 3:13–14; Words of Mormon 1:3–7; Alma 37:2; 3 Nephi 5:10), the plates of Zeniff (Mosiah 8:5), the plates of Ether (Mosiah 8:9; 28:11; Ether 1:2), and the plates of Mormon (Mormon 8:14). For evidence of writing on metal plates in antiquity, see William J. Hamblin, “Sacred Writing on Metal Plates in the Ancient Mediterranean,” FARMS Review 19, no. 1 (2007): 37–54; H. Curtis Wright, “Metallic Documents of Antiquity,” BYU Studies 10, no. 4 (1970): 457–477. See also Book of Mormon Central, “Is the Book of Mormon Like Other Ancient Metal Documents? (Jacob 4:2),” KnoWhy 512 (April 25, 2019); Book of Mormon Central, “Are There Other Ancient Records Like the Book of Mormon? (Mormon 8:16),” KnoWhy 407 (February 13, 2018).

- 3. André Lemaire, “Writing and Writing Materials,” in Anchor Bible Dictionary, 6 vols., ed. David Noel Freedman (New York, NY: Doubleday, 1992), 6:1001–1004; Philip Zhakevich, Scribal Tools in Ancient Israel (University Park, PA: Eisenbrauns, 2020), 8–123.

- 4. Alma 14:8. See Gardner, Labor Diligently, 21–22; John L. Sorenson, “The Book of Mormon as a Mesoamerican Record,” in Book of Mormon Authorship Revisited: The Evidence for Ancient Origins, ed. Noel B. Reynolds (Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies [FARMS], 1997), 417–418; Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex, 231.

- 5. For convenient collections of most of the primary source descriptions, see Kirk B. Heinrichsen, “How Witnesses Described the ‘Gold Plates’,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 10, no. 1 (2001): 16–21, 78; Matthew B. Brown, Plates of Gold: The Book of Mormon Comes Forth (American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 2003), 148–151; Jerry D. Grover Jr., Ziff, Magic Goggles, and Golden Plates: Etymology of Zyf and a Metallurgical Analysis of the Book of Mormon Plates (Provo, UT: Grover Publishing, 2015), 67–70.

- 6. Carol Ann Newsom, “Scroll,” in HarperCollins Bible Dictionary, rev. ed., ed. Mark Allan Powell (New York, NY: HarperOne, 2011), 928.

- 7. Émile Puech, The Copper Scroll Revisited (Boston, MA: Brill, 2015); Joan E. Taylor, “Secrets of the Copper Scroll,” Biblical Archaeology Review 45, no. 4 (2019): 72–78, 88.

- 8. William J. Adams Jr., “Lehi’s Jerusalem and Writing on Silver Plates,” in Pressing Forward with the Book of Mormon: The FARMS Updates of the 1990s, ed. John W. Welch and Melvin J. Thorne (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1999), 23–26; William J. Adams Jr., “More on the Silver Plates from Lehi’s Jerusalem,” in Pressing Forward, 27–28. See also Gabriel Barkay, “The Priestly Benediction in Silver Plaques from Ketef Hinnom in Jerusalem,” Tel Aviv 19, no. 2 (1992): 139–192; Gabriel Barkay, Marilyn J. Lundberg, Andrew G. Vaughan, and Bruce Zuckerman , “The Amulets from Ketef Hinnom: A New Edition and Evaluation,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 334 (2004): 41–71; Jeremy D. Smoak, The Priestly Blessing in Inscription and Scripture (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2016); Jeremy D. Smoak, “Words Unseen,” Biblical Archaeology Review 44, no. 1 (2018): 52–59, 70.

- 9. See Bruce M. Metzger, “Codex,” in HarperCollins Bible Dictionary, 140–141.

- 10. John W. Welch, “Doubled, Sealed, Witnessed Documents: From the Ancient World to the Book of Mormon,” in Mormons, Scripture, and the Ancient World: Studies in Honor of John L. Sorenson, ed. Davis Bitton (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1998), 401–404; John W. Welch and Kelsey D. Lambert, “Two Ancient Roman Plates,” BYU Studies 45, no. 2 (2006): 54–76. See also Leman Altuntas, “A 2000-Year-Old Bronze Military Diploma was Discovered in Turkey’s Perre Ancient City,” Arkeo News, January 2, 2022.

- 11. See Evidence Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Indian Copper Plate Grants,” Evidence #246, September 28, 2021; Evidence Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Lengthy Indian Plates,” Evidence #248, October 4, 2021, both online at evidencecentral.org.

- 12. Warren P. Aston, “The Rings That Bound the Gold Plates Together,” Insights: A Window on the Ancient World 26, no. 3 (2006): 3–4; Jeff Lindsay, “A ‘D’ for Plausibility of the Gold Plates: The Book of Mormon in an Interesting Bind,” Arise from the Dust (blog), August 29, 2006.

- 13. Ilana Herzig, “World’s Oldest Book,” Archaeology (January/February 2024). It is interesting to note that ten by six inches is only a couple inches off from the standard size of the Book of Mormon plates, which were approximately six by eight inches. One late, second-hand source even quotes Joseph Smith Sr. as estimating their size as “about six inches wide, and nine or ten inches long.” Fayette Lapham, “Interview with the Father of Joseph Smith, the Mormon Prophet, Forty Years Ago. His Account of the Finding of the Sacred Plates,” Historical Magazine 8, no. 5 (May 1870): 307. The typical page size of ancient books may have naturally varied by an inch or two, but if the Book of Mormon plates were patterned after the plates of brass, those plates may have had leaves about the size of the leaves in this earliest known papyrus book from Egypt.

- 14. Lemaire, “Writing and Writing Materials,” 1002–1003; Zhakevich, Scribal Tools in Ancient Israel, 96–97

- 15. R. Lansing Hicks, “Delet and Megillah: A Fresh Approach to Jeremiah xxxvi,” Vetus Testamentum 33, no. 1 (1983): 50.

- 16. Peter Kornicki and T. H. Barrett, “Buddhist Texts on Gold and Other Metals in East Asia: Preliminary Observations,” Journal of Asian Humanities at Kyushu University 2 (2017): 115–117.

- 17. Sorenson, “Book of Mormon as a Mesoamerican Record,” 412. See also Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex, 230.

- 18. Ruth K. Krochock, “Written Evidence,” in Lynn V. Foster, Handbook to Life in the Ancient Maya World (New York, NY: Facts on File, 2002), 296–299.

- 19. See John L. Sorenson, Images of Ancient America: Visualizing Book of Mormon Life (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1998), 160–163. See also Evidence Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Pre-Columbian Books,” Evidence #214 (July 19, 2021), online at evidencecentral.org.

- 20. Pierre Agrinier, “Mounds 9 and 10 at Mirador, Chiapas, Mexico,” Papers of the New World Archaeological Foundation 39 (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University, 1975), 3, 100; Nicholas P. Carter and Jeffrey Dobereiner, “Multispectral Imaging of an Early Classic Maya Codex Fragment from Uaxactun, Guatemala,” Antiquity 90, no. 351 (2016): 711–725. Interestingly, Mirador in Chiapas is Sorenson’s candidate for Ammonihah, where the records were burned. See Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex, 187n15.

- 21. Michael D. Coe, The Maya Scribe and His World (New York, NY: Grolier Club, 1973), 8.

- 22. Michael D. Coe and Justin Kerr, The Art of the Maya Scribe (New York, NY: Harry N. Abrams, 1998), 63.

- 23. See Alma 14:8; Krochock, “Written Evidence,” 297; Sorenson, Images of Ancient America, 163. It is likely that if there were ever metal books in both ancient Israel and Mesoamerica, most of them would have been plundered and melted down (see 2 Kings 25:9, 13–17).

- 24. This was pointed out to Scripture Central staff by Mark Alan Wright.

- 25. Sorenson, “Mormon’s Sources,” 13.

- 26. Noel B. Reynolds, “An Everlasting Witness: Ancient Writings on Metal,” in Steadfast in Defense of Faith: Essays in Honor of Daniel C. Peterson, ed. Shirley S. Ricks, Stephen D. Ricks, and Louis C. Midgley (Orem, UT: Interpreter Foundation; Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn, 2023), 143–158.

- 27. Krochock, “Written Evidence,” 296–297.

- 28. Book of Mormon Central, “Why Was Coriantumr's Record Engraved on a ‘Large Stone’? (Omni 1:20),” KnoWhy 77 (April 13, 2016). See Omni 1:20–22.