Evidence #246 | September 28, 2021

Copper Grants

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

Abstract

Indian copper plate grants were valued records that were often kept for future use by burial in the ground and preservation in boxes of stone and cement. A similar tradition of keeping and preserving metal records was had among the Nephites.Book of Mormon Plates

Nephite record keepers preserved some of their writings on metal plates to ensure that their more valuable records would last through time to be of benefit to future generations (Jacob 4:2–3). These writings were valued for what they represented in terms of their heritage as well as their content.

With the realization that their enemies sought to destroy their sacred records (Enos 1:13–14; Mormon 6:6), Nephite prophet-writers went to great efforts to preserve them, sometimes even burying them in the earth. Even the wicked among the Nephites sometimes tried to bury treasured possessions in the hope of eventually regaining them at a later time (Helaman 11:10, 26; Helaman 13:17–20, 33–36; Mormon 1:18). The preservation and discovery of numerous copper plate grants in India corresponds with these practices.

Royal Copper Plate Grants

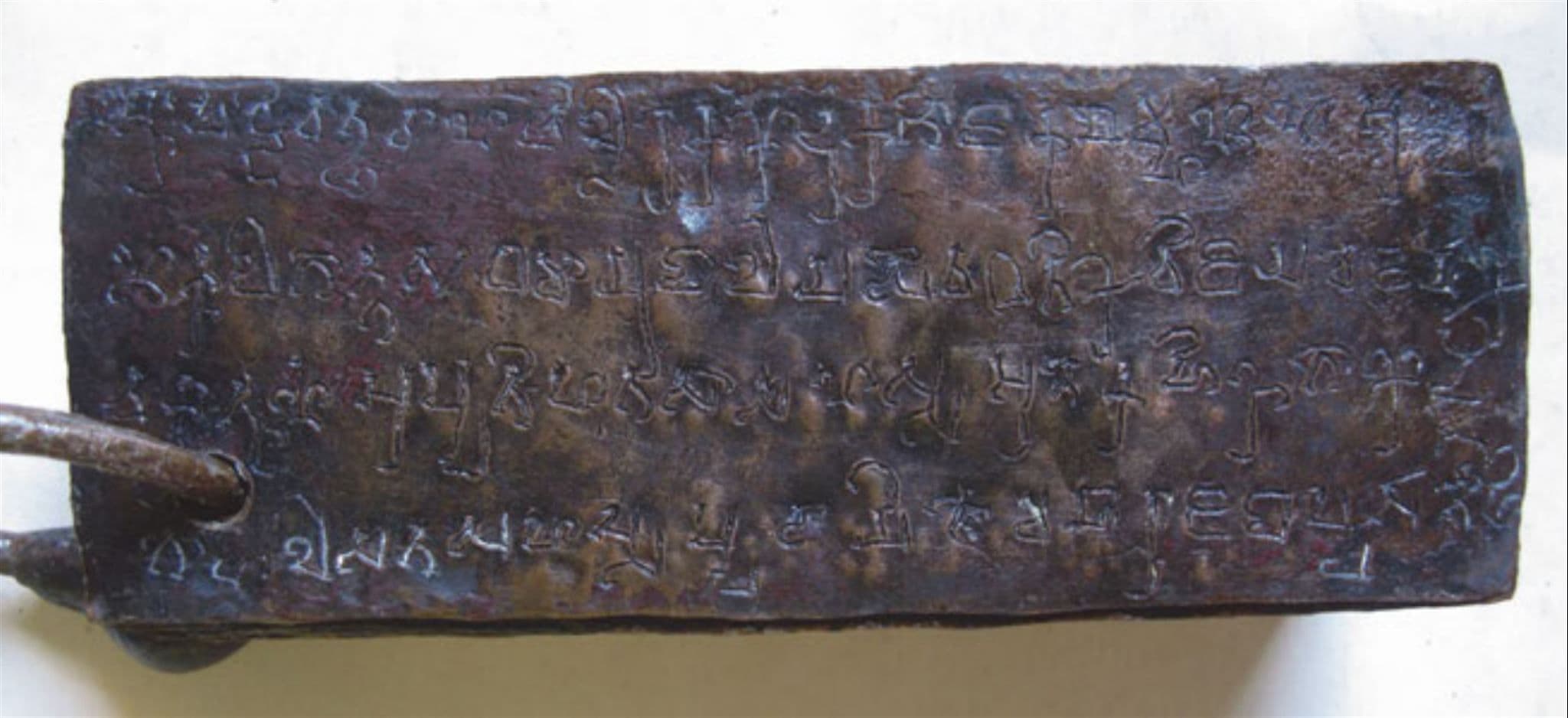

No other place in the world so far has yielded more examples of writing on metal plates than India. The majority of these are royal copper plate grants that bestowed land and privileges upon local brahmin or other religious leaders. Grants were inscribed on a single or multiple plates that were then fastened by a copper ring and a royal seal, sometimes made of bronze. Thousands of these documents have been recovered so far, and more discoveries can be expected to follow.1

Hindu law from at least AD 100–300 required that kings who bestowed grants of land and associated privileges be properly documented and honored by future rulers.

When a king makes a gift of land or bestows a nibandha he should execute a writing (about the gift) for the information of future good kings. He (the king) should issue a permanent edict bearing his signature and the date on a piece of cloth or on a copper plate marked at the top with his seal and write down thereon the name of his ancestors and of himself, the extent (or measurements) of what is gifted and set out the passages (from smrtis) that condemn the resumption of gifts.2

Copper plate grants were divided into two parts. The first was a eulogy or praśasti that detailed the ancestry of the king or ruler who bestowed the grant. As Richard Salomon explains, these often included “an account of the ruling king’s lineage, full of lavish praises of his own and his ancestors’ physical power and beauty, moral qualities and reputation, just rule, conquests, learning and artistic skills, and so on.”3 Sometimes skilled poets were employed to write praśastis that portrayed the king and his ancestors in the most superlative of terms.

The second part was the actual grant itself, which usually provided the names of grantees, the date issued, the place where it was bestowed, names of witnesses, the boundaries of the land, villages and resources to be administered, responsibilities associated with their administration, a statement of divine blessing on the royal grantor, and a warning of divine punishment against any who might violate the terms of the gift. Frequently, the grant also included an exemption from taxation.

Valued Records

Families who received grants treasured such records. “Copper plates were valuable documents and as such carefully preserved by the donee and his descendants. If lost, the revenue-free holdings created by them could again relapse into ordinary rent-paying land.”4

The Velvikudi Grant of Nedunjadaiyan is a set of ten copper plates that date to AD 769–770.5 The inscription says that during the third year of the reign of King Nedunjadaiyan (one of the Pandya kings) while he was marching through a village with his army, a bystander drawing his attention humbly begged his attention, complaining that after a long period of war his land had been unlawfully taken away. To this the king responded, “Very well, very well, prove the antiquity of the gift by a reference to the district assembly and receive it back.” The man then produced the grant. The king gladly returned the land to the man, saying, “What was granted by my ancestors according to rule, is also granted by us.”6

Tragically, those who have come into possession of such artifacts have not always appreciated their historical value. Some grants have been discarded or even melted down.7 All of this recalls the land-oriented promises and privileges found among Nephite records,8 as well the Lamanites’ efforts to destroy those records (Enos 1:14).

Ongoing Discoveries

During the last 150 years, an increasing number of copper plate grants have been discovered in various parts of India. According to Albertine Gaur, these have been found “immured in walls or foundations of houses belonging to families of donees or hidden in small caches made of bricks or stone in the fields to which the grant refers. Sometimes several different grants were kept hidden together.”9 Acharya notes that many plate grants have been discovered while farmers were cultivating fields or mounds on their land or when construction workers were renovating old wells or water tanks.10

Plate-grants, sometimes multiple grants belonging to different families, have also been discovered at temple sites in India, sometimes buried beneath the floors of buildings. A cache of 17 sets of copper plates dating to the 8–9th centuries AD (122 inscribed leaves) were discovered during renovation work at Halebelagola in 2020,11 and in early 2021 excavators at a temple at Ghanta Matham in Andhra Pradesh discovered six sets of copper plates (a total of eighteen inscribed leaves).2

Such documents may have been entrusted to local religious leaders to protect them and possibly keep them safe for future consultation if necessary. “Collective land grants were always prone to internal feuds or squabbles. The beneficiaries or their descendants might have engaged in prolonged quarrels among themselves over the possession of the original charter. In all such cases, one possible solution was to deposit the charter in the safe custody of the superintendent of the local temple.”13 One is reminded of the quarrel between the Nephites and the Lamanites over the possession of the plates of brass (Mosiah 10:16–17).

Burial and Preservation in Stone and Cement Boxes

Plates were preserved in different ways. One method was to hide them in large earthen pots that were filled with sand or husks from grain. Sometimes two holes were made in the pots for a strong stick so that the plates could be suspended from their ring inside the pot before being filled. “The pots were normally kept underground in the cultivable lands or in the backyard of the houses. Most of the plates thus kept in the earthen vessels were found in a good state of preservation.”14

Acharya notes that another way of preserving royal copper plate grants in India was by storing them in stone and cement boxes which were sometimes buried in the ground. He documents numerous examples from Orissa beginning in the 8–9th century AD.15 He suggests “the stone boxes were probably prepared under the supervision of the royal officers and given to the donees at the time of registering the land grants by means of copper plate charters.”16 Historical texts indicate that the royal officer responsible for engraving the royal seal on plate grants was designated by a term that means “keeper of the boxes” apparently in reference to his role as record keeper when grants were issued.17 This practice is reminiscent of Joseph Smith’s description of the box that contained the plates revealed by Moroni (JSH 1:52).18

Conclusion

Although some examples of copper plates from India were known in the West at the time the Book of Mormon was published, most examples known today were discovered and published after the publication of the Book of Mormon. These discoveries show that cultures in India had a robust and well-established tradition of inscribing records on copper that far exceeds what could have been anticipated by Joseph Smith or most early nineteenth-century Americans.

The sheer quantity of the copper plate grants, their presentation of genealogies, their bestowal of land-oriented privileges, their issuing of warnings or blessings, the disputations over their ownership and associated rights, and the efforts made to preserve them (often in stone boxes) from loss or destruction, are all analogous with the content and preservation of the Book of Mormon and the numerous ancient records it describes.

Book of Mormon Central, “Are There Other Ancient Records Like the Book of Mormon? (Mormon 8:16),” KnoWhy 407 (February 13, 2018).

William J. Hamblin, “Sacred Writing on Metal Plates in the Ancient Mediterranean,” FARMS Review 19, no. 1 (2007): 37–54.

H. Curtis Wright, “Ancient Burials of Metal Documents in Stone Boxes,” in “By Study and Also By Faith”: Essays in Honor of Hugh Nibley, 2 vols., ed. John M. Lundquist and Stephen D. Ricks (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1990), 273–334.

H. Curtis Wright, “Metallic Documents in Antiquity,” BYU Studies Quarterly, 10, no. 4 (1970): 457–477.

Book of MormonJacob 4:2–3Enos 1:13–14Mosiah 10:16–17Helaman 11:10Helaman 11:26Helaman 13:17–20Helaman 13:33–36Mormon 1:18Mormon 6:6Pearl of Great PriceJSH 1:52Book of Mormon

Pearl of Great Price

- 1 Richard Salomon, Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Praakrit, and Other Indo-Aryan Languages (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1998), 113; T.S. Sridhar and R. Balasubramanian, A Catalogue of Copper Plate Grants 1918–2010 (Chennai: Commissioner of Museums, Government Museum, Chennai, 2001). A catalogue of copper-plate inscriptions published in 2014 documented over 400 plates or sets of plates from the state of Odisha alone. Subrata Kumar Acharya, Copper-plate Inscriptions of Odisha: A Descriptive Catalogue (Circa Fourth Century to Sixteenth Century) (Ramesh Nagar, New Dehli: DK Printworld, 2014); Subrata Kumar Acharya, “Kings, Brahmanas and Collective Land Grants in Early Medieval Odisha,” Indian Historical Review 45, no. 1 (2018): 24–57.

- 2 Padurang Vaman Kane, History of Dhamasastra: Ancient and Medieval Religious and Civil Law in India, 5 vols. (Poona: Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, 1941), 2:860–861. See also Vishnusutra III:82 in Julius Jolley, trans., The Institutes of Vishnu (Dehli: Motilal Banarsidass, 1970), 21–22.

- 3 Salomon, Indian Epigraphy, 112.

- 4 Albertine Gaur, Indian Charters on Copper Plates in the Department of Oriental Manuscripts and Printed Books (London: Published for the British Library by British Museum Publications, 1975), vii–viii.

- 5 Krishna Sastri, “Velvikudi Grant of Nedunjadaiyan: The Third Year of Reign,” Epigraphia Indica 17 (1923–1924): 291–309. See also Gaur, Indian Charters on Copper Plates in the Department of Oriental Manuscripts and Printed Books, 2–4.

- 6 Sastri, “Velvikudi Grant of Nedunjadaiyan,” 308.

- 7 Subrata Kumar Acharya, “Ancient Methods of Preserving Copper Plate Grants,” Indian Journal of History of Science 43, no. 2 (2008): 268. In his attempts to track down and identify copper plates in eastern India, Acharya uncovered another tragedy. During the British occupation “unscrupulous officers demanded the surrender of title deeds in any form from the proprietors of land or landowners with the intention to make land settlements. As a result a number of small landholders surrendered their title deeds to the British officers, but could not get back their deeds. There are reports from learned epigraphists that when they chanced to see the record offices of the collectorates, they could find such deeds kept unnoticed. Sometimes they were either melted away or smuggled out.” Acharya, Copper-plate Inscriptions of Odisha, xxxvii.

- 8 See Book of Mormon Central, “What does it Mean to ‘Prosper in the Land’? (Alma 9:13),” KnoWhy 116 (June 7, 2016).

- 9 Gaur, Indian Charters on Copper Plates in the Department of Oriental Manuscripts and Printed Books, viii.

- 10 Acharya, “Ancient Methods of Preserving Copper Plate Grants,” 265–266.

- 11 R. Krishna Kumar, “Discovery of Copper Plate Inscriptions at Halebelegola Excites Scholars,” The Hindu, November 22, 2020.

- 12 “21 Copperplate Inscriptions Discovered at Ghanta Matham in India,” Arkeonews, June 14, 2021.

- 13 Acharya, “Ancient Methods of Preserving Copper Plate Grants,” 270.

- 14 Acharya, “Ancient Methods of Preserving Copper Plate Grants,” 267.

- 15 Acharya, “Ancient Methods of Preserving Copper Plate Grants,” 270–272. “Another method of preserving the copper plate grants is preparing a square or rectangular stone box or casket and keeping the plates inside it. Chronologically, the Chaurasi plate of Sivakaradeva (8–9th century AD) is the earliest inscription preserved in this manner. Of course the box containing the inscription is not made of stone; it is a cemented brick cabinet. The inscription is written on both sides of a single plate measuring 8 x 8½”. A few inscriptions of the Sonepur-Athamallik-Angul were also preserved similarly. The Sonepur plates of Somavamsi Janamejaya I (late 9th-early 10th century) were found concealed in a massive oblong stone coffer, measuring 16¾” long with a slipping lid which was obviously designed for the safe deposit of the charter. The plates measure 8¼ x 5¼” each. The Kankala plates of the Bhanja king Ranabhanjadeva (9th century AD) were discovered while excavating an old tank in 1968 in the village of Kankala, only four miles from Athamallik, in the present Baud district of Orissa. The three inscribed plates with the seal-ring were well preserved in a square-size heavy stone box. The plates measure 7½ x 44/5’’ each. The Angul plates of Santikara of an unknown family (10th century AD) were also found preserved in a stone casket at the time of discovery. Later on, some of the charters of the Imperial Gangas of the 13–14th centuries were also found concealed in huge stone boxes. In 1892, when the Kendrapara canal in the former Cuttack district was being dug, a stone-box was found, 19 or 20 feet below the surface of the earth, in the village Kendupatana. The box which was 3 feet square with a height of 2 feet, contained three sets of inscribed copper plates (each having seven plates) belonging to the Ganga king Narasimhadeva II (1278–1305 AD). The three sets measure 14 x 8¾”, 13 x 9¼”, and 13 x 9” respectively. This is the heaviest stone-box containing the plates so far discovered in Orissa. For long the box together with the plates was preserved in the local temple of Laksminarayana. The Alapur plates of the same king are also reported to have been preserved in a stone box. The Kenduli plates of Narasimhadeva IV of saka. 1305 (1383 AD) were discovered in a stone case when a tank was excavated in the village of Kenduli near Balipatana in the Puri district. Outside Orissa, the Kalegaon (Ahmednagar district, Maharashtra) plates of Yadava Mahadeva of 1201 AD were found inside a stone-box made of two slabs of stone firmly joined together.” Acharya, “Ancient Methods of Preserving Copper Plate Grants,” 270–272; slight adjustments made to style formatting.

- 16 Acharya, “Ancient Methods of Preserving Copper Plate Grants,” 272.

- 17 Acharya, “Ancient Methods of Preserving Copper Plate Grants,” 272.

- 18 For further information on the box containing the Book of Mormon, as well as the use of boxes to preserve other ancient records, see Benjamin R. Jordan and Warren P. Aston, “The Geology of Moroni’s Stone Box: Examining the Setting and Resources of Palmyra,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 30 (2018): 233–252; H. Curtis Wright, “Ancient Burials of Metal Documents in Stone Boxes,” in By Study and Also By Faith: Essays in Honor of Hugh W. Nibley, Volume 2, ed. John M. Lundquist and Stephen D. Ricks (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1990), 273–334.