Evidence #228 | August 23, 2021

Plates and Ritual

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

Abstract

Known examples of ancient metal plates feature ritual content similar to the information on the plates of brass and the plates of the Book of Mormon.Ritual Content and the Book of Mormon

Nephi recorded that the plates of brass contained the Law of Moses (1 Nephi 4:14–16). These records enabled the Nephites to remember and keep the commandments and performances of that law for hundreds of years (2 Nephi 5:10; Alma 25:15–16).1 This included the Israelite practice of animal sacrifice which continued among the people of Nephi until the visitation of the resurrected Jesus (Mosiah 2:3; 3 Nephi 9:19).

Nephite record keepers also described other sacred ordinances including commandments and instructions concerning baptism (2 Nephi 9:23–24; 31:4–13; Mosiah 18:8–14; Alma 7:14–16; 3 Nephi 11:21–27), and the sacrament of bread and wine (3 Nephi 18:1–14; Moroni 4:1–3; 5:1–2). The practice of recording sacred rituals, including instructions concerning animal sacrifice and baptism on metal plates finds support in new discoveries made since the publication of the Book of Mormon.

Animal Sacrifice and the Iguvine Plates

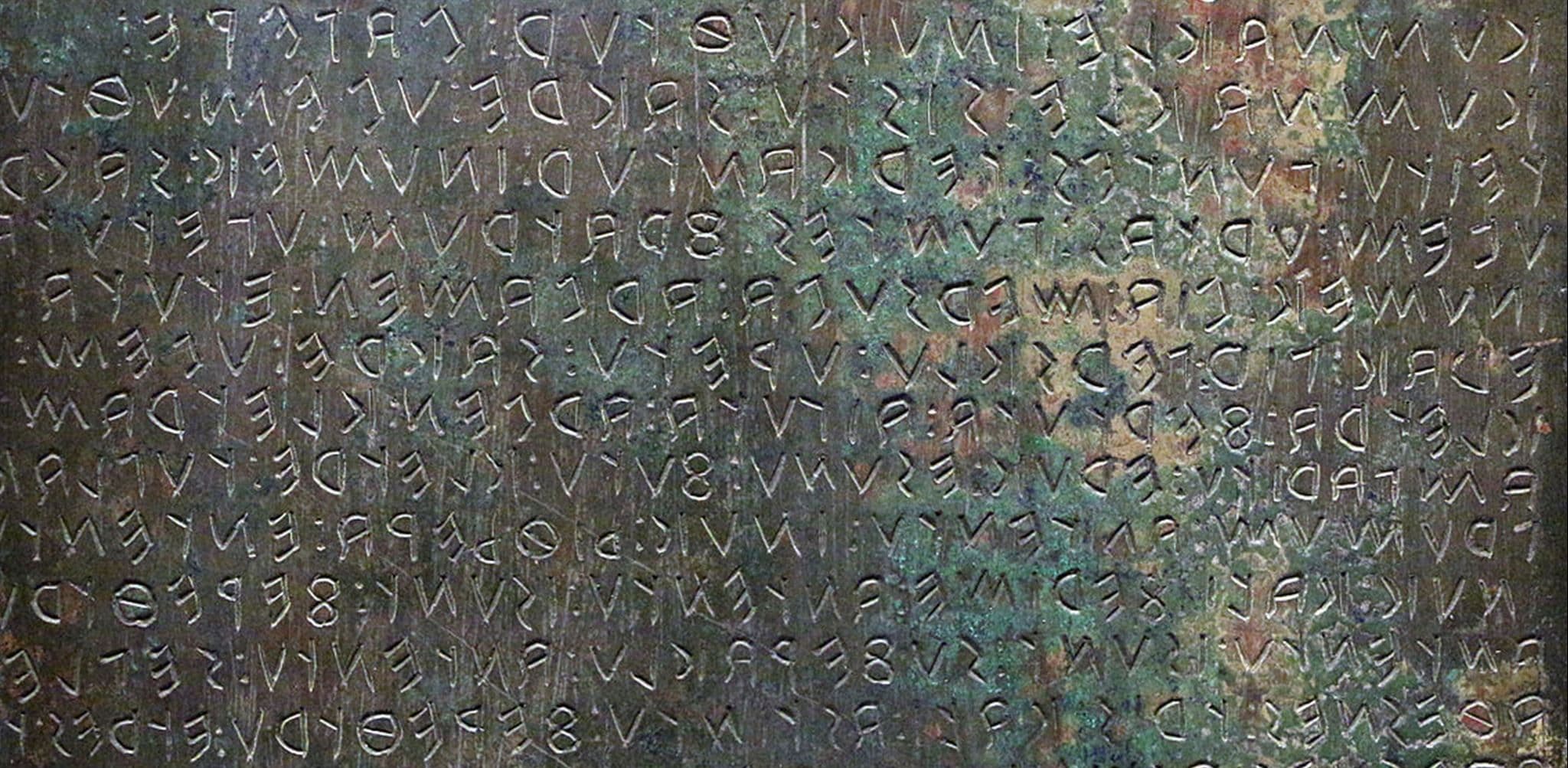

The Iguvium (or Iguvine) Tablets are a set of seven bronze plates that were discovered in the 14th Century in a farmer’s field in the Italian town of Gubbio.2 The inscriptions, written partly in Umbrian and partly in Latin, were first published in 18643 and not in English until 1959.4

Five of the plates are engraved on both sides, constituting over 4000 words. They are believed to date to between the Third and First Centuries BC and are known to be one of only two large ritual documents that have so far been recovered from the ancient Classical world.5 According to William Poultney, “No other body of liturgical texts from pre-Christian Europe can compare with the Iguvine Tables in extent. They have therefore an extraordinary importance both for the linguistic and the religious history of early Italy.”6 Augusto Ancillotti and Romolo Cerri describe it as “the most significant ritual text of classical antiquity.”7 They write,

The Tables have been engraved in different periods and by different hands, and this was generally done in order to make unperishable texts formerly written on perishable material (such as linen or parchment). The presence of hanging holes is due to the fact that in later times (maybe in the Augustan period) the Tables were displayed in public, probably so as to extol the nobility of the Iguvian cultural roots.8

The text contains instructions to the Atiedian Brotherhood (the Umbrian priests of the ancient community) on the performance animal sacrifices and other related activities associated with the purification of the sacred hill precinct of the town. Sacrificial offerings of cattle, lambs, pigs, rams, and dogs are described in connection with offerings of grain and wine.9 Other rituals are mentioned including one which scholars have compared to a scapegoat ritual.10 Although they represent rituals of a different and non-Israelite culture, they are, as William Hamblin noted, the sociological equivalent of the instructions of sacrifice and offerings of the law of Moses similar to what we find in the book of Leviticus which would have been contained on the plates of brass and practiced by the Nephites.11

Mandaean Rituals and Metal Plates

The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran are a non-Christian gnostic sect that has historical roots in early Judaism and Mesopotamian religion.12 In the mid-Twentieth Century Lady E. S. Drower, who studied and lived among the Mandaeans for many years, collected and published many of their texts. Mandaean tradition holds that the “holy doctrines were never written on parchment (since slaying is the destruction of life, the skins of animals are unclean), but on papyrus, metal, and stone.”13 She reported being shown a book written on lead plates which was a copy of the Mandaean baptism liturgy, the Sidra d Nishmatha (Book of Souls), and the liturgical prayers of the Masiqta, an ascension ritual performed for dead Mandaeans.14 Both the baptismal and Masiqta liturgies are believed to be very old dating back to the 3rd Century AD and possibly earlier.15 Both liturgies were translated into English and included as part of a longer collection published in 1959.16

Prayers from Book of Souls are recited by the priest during Mandaean baptisms and contain instructions for the baptized. Prayer 18 reads, “Let every man whose strength enableth him and who loveth his soul, come and go down to the Jordan and be baptized and receive the Pure Sign; put on robes of radiant light and set a fresh wreath on his head.”17 Having spoken these words, the text instructs the Mandaean priest to baptize the individual, telling them, “Thy baptism will protect thee and be efficacious.”18 The concluding portion of the liturgy, Prayer 31, recites how Hibil-Ziwa, a heavenly being, once visited and introduced baptism to Adam who was subsequently baptized just as the Mandaean participant was baptized.19 The text ends with a colophon stating that this was “the (baptism) wherewith Hibil Ziwa baptized Adam the first man and it was preserved in the ages for the elect righteous.”20

Prayers for the Masiqta ritual tell how, upon death, the soul ascends through heaven in order to return to its original home. Before it can proceed it is required to pass by Abathur, a heavenly guardian, who questions the soul. “There his scales are set up and spirits and souls are questioned before him as to their names, their signs, their blessing, their baptism and everything that is therewith!”21 Once properly examined and judged worthy to proceed, the soul is able to enter the House of Life.22 The use of metal plates to inscribe sacred texts associated with baptism and other rituals is notable.

Conclusion

The rituals recorded on the bronze Iguvine Tables show that significant descriptions of sacrificial worship were sometimes recorded on metal plates in antiquity, a practice consistent with Nephi’s testimony that the plates of brass contained the law of Moses with its own system of Israelite sacrifice (see the Appendix for a chart of the similarities involved). Mandaean ritual texts, including some associated with the practice of baptism, also mirror content in the Book of Mormon, in which baptism and its proper administration is an essential and prominent doctrine. This evidence, however, for comparable sacred rituals recorded on metal plates was not available to Joseph Smith in 1829. Neither the Iguvine Tables nor the Mandaean ritual texts were published at that time, nor would they be translated into English until the mid-twentieth century.

Book of Mormon Central, “Is the Book of Mormon Like Other Ancient Metal Documents? (Jacob 4:2),” KnoWhy 512 (April 25, 2019).

Book of Mormon Central, “Are There Other Ancient Records Like the Book of Mormon? (Mormon 8:16),” KnoWhy 407 (February 13, 2018).

William J. Hamblin, “Sacred Writing on Metal Plates in the Ancient Mediterranean,” FARMS Review 19, no. 1 (2007): 37–54.

H. Curtis Wright, “Ancient Burials of Metal Documents in Stone Boxes,” in “By Study and Also By Faith”: Essays in Honor of Hugh Nibley, 2 vols., ed. John M. Lundquist and Stephen D. Ricks (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1990), 273–334.

H. Curtis Wright, “Metallic Documents in Antiquity,” BYU Studies Quarterly, 10, no. 4 (1970): 457–477.

2 Nephi 5:102 Nephi 9:23–242 Nephi 31:4–13Mosiah 2:3Mosiah 18:8–14Alma 7:14–16Alma 25:15–163 Nephi 9:193 Nephi 11:21–27Iguvium Plates (Poultney Translation) | Law of Moses |

Before the Trebulan Gate sacrifice three oxen to Jupiter Grabovius (158). Behind the Trebulan Gate sacrifice three pregnant sows to Trebus Jovius (158). Behind the Veian Gate sacrifice three lambs to Tefer Jovius (160). | And he shall kill the bullock before the Lord (Leviticus 1:5). And of his offering be of the flocks, namely the sheep, or of the goats … he shall kill it on the side of the altar northward before the Lord (Leviticus 1:10–11). |

Consecrate the pig brought away and without blemish, which has been selected, and pronounce it free from blemish (192–194). Consecrate and pronounce upon the he-goat brought from away and without blemish, which has been selected. Slay it outside and present it in the temple (194). Then slay the unblemished sheep (206–208). | Let him offer a male without blemish. He shall offer it at the door of the tabernacle of the congregation before the Lord (Leviticus 1:3). He shall bring it a male [sheep or goat] without blemish (Leviticus 1:10). |

Present grain offerings (194) Pray each (portion) in a murmur with (offerings of) fat and grain (158). | When any will offer a meal offering unto the Lord, his offering shall be of fine flour (Leviticus 2:1) Offering of the fat (Leviticus 3:9) |

| Then at the third side of the altar cut off three pieces as burnt offerings; present them from the top of the altar toward the statue, to Vesona of Pomonus Poplicus (208–210). | Divided pieces of the sacrificial animal laid upon the altar for a burnt sacrifice [burnt offering]to the Lord (Leviticus 1:7–9). |

While you are slaying it, wear a stole on your right shoulder (198). | Priestly Clothing worn while performing sacrifices (Leviticus 6:10–11). |

| He shall place fire on the altar (178). | And the sons of Aaron the priest shall put fire upon the altar and lay the wood in order upon the fire (Leviticus 1:7). |

Sacrifice either with wine of with mead (158). Pour a libation, and dance the tripudium, offering wine at each turning … He shall pour a libation from a bowl to Hondus Jovius (182–186). | Thou cause the strong wine to be poured unto the Lord for a drink offering (Numbers 28:7). |

| If in thy sacrifice there hath been any omission, any sin, any transgression, any damage, any delinquency, if in thy sacrifice there be any seen or unseen fault, Jupiter Grabovius, if it be right, with this perfect ox as a propitiatory offering may purification be made (244). | If a soul shall sin through ignorance against any of the commandments of the Lord concerning things which ought not to be done and shall do against any of them (Leviticus 4:2). |

- 1 See Evidence Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: To Remember and to Forget,” September 19, 2020, online at evidencecentral.org.

- 2 James Wilson Poultney, The Bronze Tables of Iguvium (Baltimore, MD: American Philological Association, 1959); Augusto Ancillotti and Romolo Cerri, The Tables of Iguvium: Color Photographs, Facsimiles, Transliterated Text, Translation and Comment (Italy: Edizioni Jama Perugia, 1997).

- 3 Francis W. Newman, The Text of the Iguvine Inscriptions, with Interlinear Latin Translation and Notes (London: Trubner and Co., 1864).

- 4 James Wilson Poultney, The Bronze Tables of Iguvium, 157–294.

- 5 Ancillotti and Cerri, The Tables of Iguvium, 35, 38.

- 6 James Wilson Poultney, The Bronze Tables of Iguvium, 1.

- 7 Ancillotti and Cerri, The Tables of Iguvium, 103.

- 8 Ancillotti and Cerri, The Tables of Iguvium, 38.

- 9 Poultney, The Bronze Tables of Iguvium, 158–172.

- 10 Irene Rosenzweig, Ritual and Cults of Pre-Roman Iguvium (London: Christophers, 1937), 40.

- 11 William J. Hamblin, “Sacred Writing on Metal Plates in the Ancient Mediterranean,” FARMS Review 19, no. 1 (2007): 51.

- 12 Edmondo Lupieri, The Mandaeans: The Last Gnostics (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 2001); Jorunn Jacobsen Buckley, The Mandaeans: Ancient Texts and Modern People (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002).

- 13 E. S. Drower, The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran: Their Cults, Customs, Magic, Legends, and Folklore (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1962), 23.

- 14 Drower, The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran, 23, 132. She also reported “a pious priest in Litalia is preparing a Sidra d Nishmatha of copper sheets inlaid with silver” (23).

- 15 Buckley, The Mandaeans: Ancient Texts and Modern People, 12.

- 16 E. S. Drower, The Canonical Prayerbook of the Mandaeans (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1959), 1–61.

- 17 Drower, The Canonical Prayerbook of the Mandaeans, 13.

- 18 Drower, The Canonical Prayerbook of the Mandaeans, 14.

- 19 Drower, The Canonical Prayerbook of the Mandaeans, 28–30.

- 20 Drower, The Canonical Prayerbook of the Mandaeans, 32.

- 21 Drower, The Canonical Prayerbook of the Mandaeans, 45.

- 22 Drower, The Canonical Prayerbook of the Mandaeans, 46.