Evidence #230 | August 31, 2021

Mesoamerican Judges

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

Abstract

Historical sources indicate that various kinds of judges were known in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica that are consistent with what is said about judges in the Book of Mormon.Judges in the Book of Mormon

Following the death of King Mosiah, the Nephites adopted a system of judges who governed the land. As described by Mosiah, judges were established at multiples levels to govern according to the laws of God.

And now if ye have judges, and they do not judge you according to the law which has been given, ye can cause that they may be judged of a higher judge. If your higher judges do not judge righteous judgments, ye shall cause that a small number of your lower judges should be gathered together, and they shall judge your higher judges according to the voice of the people. (Mosiah 29:28–29)

The judges were established by the voice of the people “throughout all the land” (Mosiah 29:41) at a local community or city level (Alma 14:4; 30:21), as well as higher levels with a chief judge presiding over the entire people (Mosiah 29:42; Alma 1:2; 4:17; 50:39–40).

Judges and the Aztec Legal System

While there is much we have yet to learn about pre-Columbian legal systems, available historical evidence shows that judges were an important part of several Mesoamerican societies. The Aztec system, for which there is the best documentation, had a multilevel system of officials who served as judges.1 According to Francisco Avalos, in a valuable analysis based upon historical sources,

There is general agreement on the structure of the Aztec legal system, which was based on a hierarchical structure similar to our own, composed of general jurisdiction courts of first instance, general jurisdiction courts, and a Supreme Justice. There were also courts that might be compared to our justice of the peace courts and special jurisdiction courts. The emperor had the legal power to hear any cases that were of importance to him or to the Empire.2

At the lower level, there were judges in each neighborhood who were elected each year to judge civil cases and minor criminal offences.3 Outside of the local community, there were the Teccalli courts, an appellate court for commoners consisting of three or four judges.4 There were also magistrates who presided over courts of special jurisdiction, such as the market, financial matters, the military, artisans, and religious cases.5

At the next level, there were Tlacxiltan courts, to which appeals from the Tecalli were sent and which was also the first level of appeal for the noble class. The judges of these courts met in a room of the palace designated for that purpose. According to Thomas Joyce, this higher court “dealt principally with high affairs of state and matters affecting the higher ranks, though it also pronounced sentences upon the cases sent up by the lower court.”6 From there, difficult cases could be appealed to a supreme court thought to have consisted of a dozen judges including a Cihuacoatl or Chief Justice who could rule on matters or in rare circumstances send the matter to the Emperor for a decision.7

The Florentine Codex, an important source of information on pre-Columbian Aztec society, describes judges as follows.

The magistrate [is] a judge, a pronouncer of sentences, and establisher of ordinances, of statutes. [He is] dignified, fearless, courageous, reserved, stern-visaged. The good magistrate [is] just: a hearer of both sides, an examiner of both sides, a listener to all factions, a passer of just sentences, a settler of quarrels, a shower of no favor. He fears no one; he passes just sentences; he intercedes in quarrels; he shows no bias. The bad magistrate [is] a shower of favor, a hater of people, an establisher of unjust ordinances, an acceptor of bribes, an issuer of corrupt pronouncements, a doer of favors [with partiality].8

Judges were strictly charged by the rulers to be honest and impartial and could be severely punished when negligent or corrupt in their duty.9 Avalos observes that “Aztec judges had not only legal responsibilities to state the law and to judge, but political, military, religious, and other responsibilities.”10 Similarly, some Nephite judges were also high priests and Elders of the Church (Mosiah 29:42; Alma 4:16–18), as well as military leaders (Alma 2:16; 62:7).

Aztec judges were assigned personnel to assist them, including scribes to keep a record of cases, bailiffs to apprehend the accused, summoners to gather witnesses, and messengers.11 Similarly, Nephite judges also developed a need for “many officers” (3 Nephi 6:11), messengers (Alma 61:1), and other officials (Helaman 2:6–10).

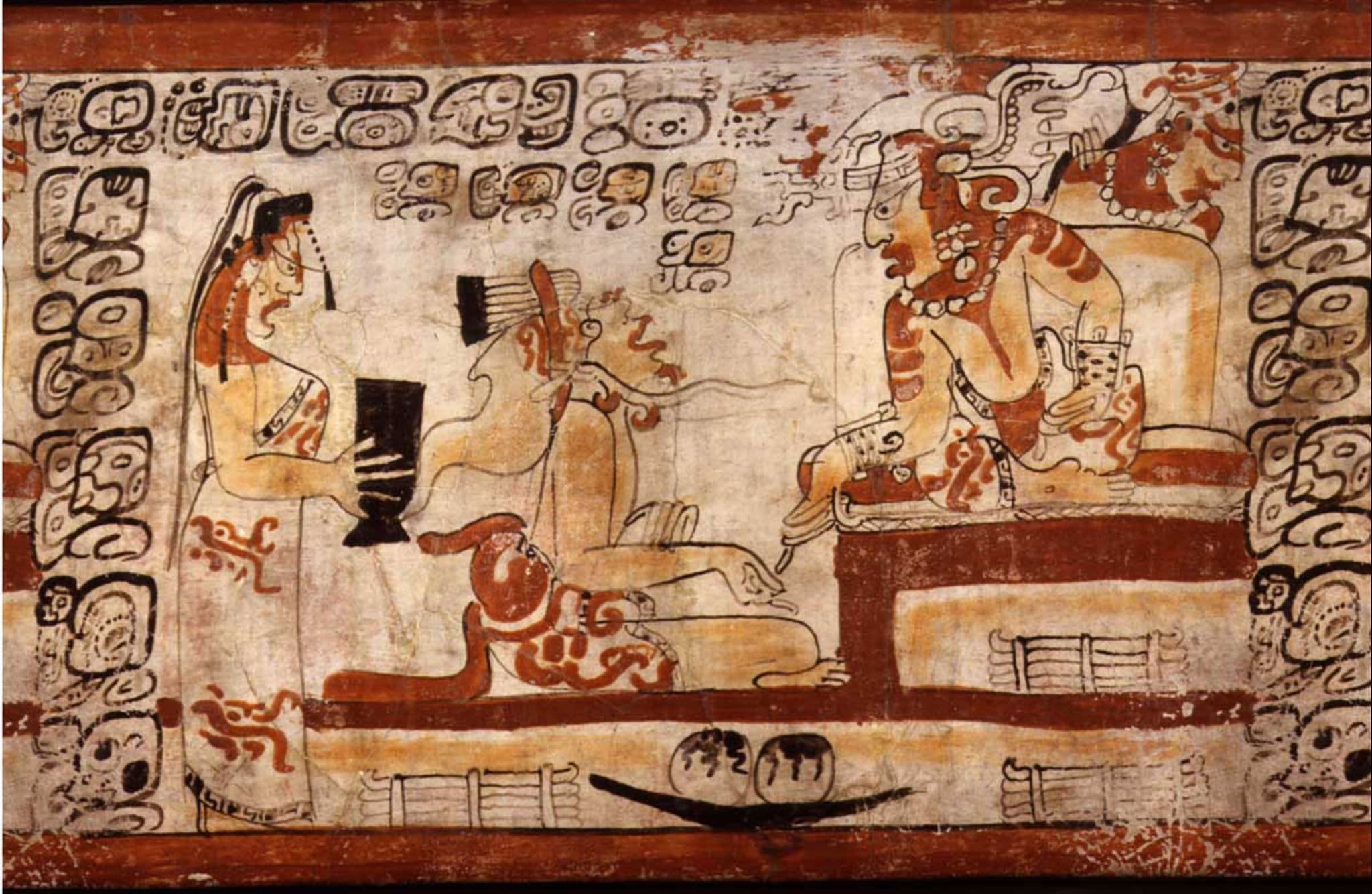

Maya Judges

Less historical information is available on the legal systems of the ancient Maya, but available evidence suggests that judges were also known among them in pre-Columbian times. Gasper Antonio Chi whose Relacion on the customs of Maya of Yucatan is an important source of information stated, “(To listen to) lawsuits and public petitions, the Lord had a governor (in the towns or) a person of rank. He received the disputants, and having heard (the cause of their coming,) discussed it with the Lord, especially if the business was serious.”12 Kings of the Tzutujil Maya of highland Guatemala had a council of officials who acted as judges and advisors and “judged criminal cases involving high rank.”13

A system of judges also functioned among the Kachiquel Maya. Their capital at Patinamit had a place where judges would hold court.

To the westward of the city there is a little mount that commands it; on this eminence stands a small round building, about 6 feet in height, in the middle of which there is a pedestal formed of a shining substance …. Seated around this building, the judges heard and decided upon the causes brought before them; and here also their sentences were executed. Previous, however, to carrying a sentence into effect, it was necessary to have it confirmed by the oracles: for which purpose, 3 of the judges quitted their seats, and proceeded to a deep ravine, where there was a place of worship, wherein was placed a black transparent stone … on the surface of this tablet the Deity was supposed to give a representation of the fate that awaited the criminal: if the decision of the judges was approved, the sentence was immediately inflicted; on the contrary, if nothing appeared on the stone, the accused was set at liberty.14

Consulting God in matters of judgment is also present in the Book of Mormon. During a time of confusion about who should judge sinners and what types of judgments should be given, Alma the Elder “went and inquired of the Lord what he should do concerning this matter” (Mosiah 26:13). Although the manner in which God’s answer was communicated to Alma isn’t stated, ancient Israelites used various oracles—including the Urim and Thummim, which is believed to have been made of some type of stone or gem—to determine God’s will.15 The Nephites and Jaredites had similar stone-related instruments used for revealing the will of God, including in matters of passing judgment or discovering wickedness (Alma 37:23–25).16

Conclusion

Current historical evidence shows that several kinds of judges were known in ancient America. The evidence is notable, not only for the existence of judges, but for hierarchical, multi-level systems of judges, a level of social complexity also suggested by the Nephite text. The evidence that judges, like those described in the Book of Mormon, filled military and religious roles as well is also significant. At the time of the publication of the Book of Mormon, Native American’s were not generally believed to be capable of the type of social and legal complexity found in its pages. It can now be seen that the Nephite system of judges fits well in an ancient American context.

Brant A. Gardner, Traditions of the Fathers: The Book of Mormon as History (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2015), 251–252.

John L. Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex: An Ancient American Book (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book and the Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2013), 375–378.

John L. Sorenson, Images of Ancient America: Visualizing Book of Mormon Life (Provo, UT: Research Press, 1998), 108–117.

Mosiah 29:28–29Mosiah 29:41Mosiah 29:42Alma 1:2Alma 2:16Alma 4:16–18Alma 4:17Alma 14:4Alma 30:21Alma 50:39–40Alma 61:1Alma 62:73 Nephi 6:11- 1 Francisco Avalos, “An Overview of the Legal System of the Aztec Empire,” Law Library Journal 86, no, 2 (1994): 259–276.

- 2 Avalos, “An Overview of the Legal System of the Aztec Empire,” 262.

- 3 Alonso de Zorita, Life and Labor in Ancient Mexico: The Brief and Summary Relation of the Lords of New Spain, trans. Benjamin Keen (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1994), 126; Avalos, “An Overview of the Legal System of the Aztec Empire,” 264.

- 4 Zorita, Life and Labor in Ancient Mexico, 126; Avalos, “An Overview of the Legal System of the Aztec Empire,” 263.

- 5 Thomas A. Joyce, Mexican Archaeology: An Introduction to the Archaeology of the Mexican and Mayan Civilizations of Pre-Spanish America (New York, NY: Kraus Reprint, 1969), 13—131; Avalos, “An Overview of the Legal System of the Aztec Empire,” 264.

- 6 Joyce, Mexican Archaeology, 130.

- 7 Joyce, Mexican Archaeology, 130; Zorita, Life and Labor in Ancient Mexico, 126; Avalos, “An Overview of the Legal System of the Aztec Empire,” 263. The number of judges being 12 may also be significant. See Evidence Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Symbolism of the Numbers 12 and 24,” September 19, 2020, online at evidencecentral.org.

- 8 Bernardino de Sahagun, General History of the Things of New Spain, 13 Parts (Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research, University of Utah, 1961), 11: 15–16.

- 9 Jerome A. Offner, Law and Politics in Aztec Texcoco (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 251–252; Zorita, Life and Labor in Ancient Mexico, 128.

- 10 Avalos, “An Overview of the Legal System of the Aztec Empire,” 262.

- 11 Offner, Law and Politics in Aztec Texcoco, 253; Zorita, Life and Labor in Ancient Mexico, 128; Avalos, “An Overview of the Legal System of the Aztec Empire,” 264.

- 12 Gasper Antonio Chi, Relacion, in Landa’s Relacion de las Cosas de Yucatan, ed., and trans. Alfred M. Tozzer (Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, 1941), 231.

- 13 Sandra L. Orellana, The Tzutujil Mayas: Continuity and Change, 1250—1630 (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1984), 92.

- 14 Domingo Juarros, A Statistical and Commercial History of the Kingdom of Guatemala (London: John Hearne, 1823), 384. For more information about divining rituals in ancient Mesoamerica, see Marc G. Blainey, “Techniques of Luminosity: Iron-Ore Mirrors and Entheogenic Shamanism among the Ancient Maya,” in Manufactured Light: Mirrors in the Mesoamerican Realm, ed. Emiliano Gallaga M. and Marc G. Blainey (Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado, 2016), 179–206; John J. McGraw, “Stones of Light: The Use of Crystals in Maya Divination,” in Manufactured Light, 207–227; Olivia Kindl, “The Ritual Uses of Mirrors by Wixaritari (Huichol Indians),” in Manufactured Light, 255–283; Karl Taube, “Through a Glass, Brightly: Recent Investigations Concerning Mirrors and Scrying in Ancient and Contemporary Mesoamerica,” in Manufactured Light, 285–314.

- 15 See John W. Welch, The Legal Cases in the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: BYU Press and Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2008), 96–97; Evidence Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Interpreters, Teraphim, and the Urim and Thummim,” September 19, 2020, online at evidencecentral.org.

- 16 See Evidence Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Similarities between the Nephite Interpreters and the Urim and Thummim,” September 19, 2020, online at evidencecentral.org.