November 11, 2024

Everything Heretic Gets Right and Wrong about Mormonism

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

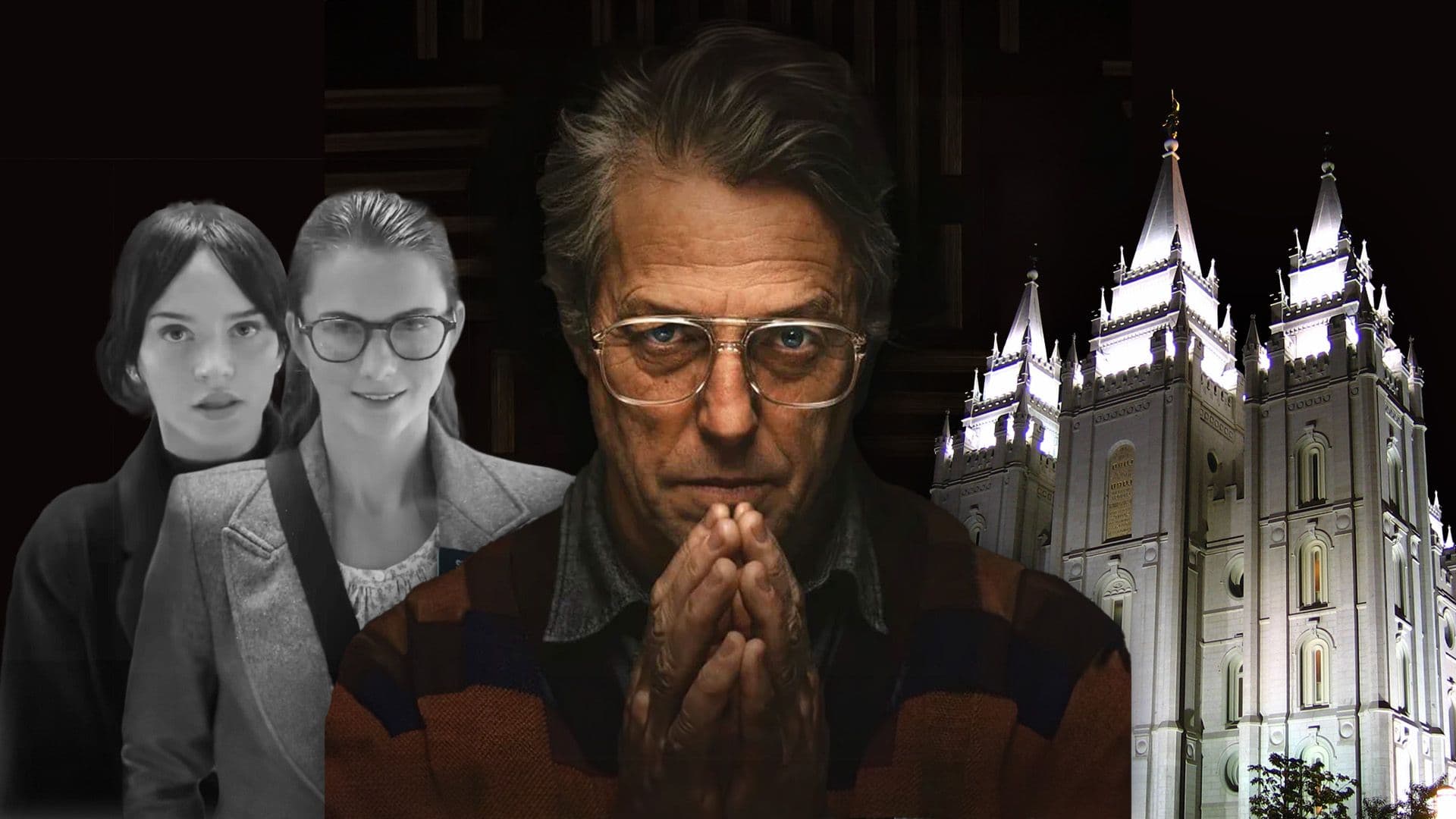

Heretic is a fictional horror film featuring two sister missionaries of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (sometimes known as the Mormon Church). They fight to survive a deadly game of cat and mouse as the villainous and twisted Mr. Reed (played by Hugh Grant) traps them in his house and strings them along a horrific path of religious deconstruction.

Because this movie may not be everyone’s cup of tea, I watched it so that you don’t have to. It’s violent, disturbing, and it has some jump scares. Today I’m going to fact check nearly every religious thing in this film. At the end, I’ll give my take and overall review on how well I think Heretic did representing my own faith.

I’m Jasmin. I’m an active, believing, practicing Latter-day Saint. And I study the history, beliefs, and practices of my Church as part of my job at a non-profit educational organization called Scripture Central. If you’re interested in religion, and specifically learning about the history and beliefs of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, you may enjoy checking out some of the other videos on this channel or consider making a donation to Scripture Central.

People have already been posting reviews and opinion pieces and official statements on the dangers of portraying religion as this film does, and I think those perspectives are worth taking seriously. But I also wanted to just take a thoughtful look at what the movie Heretic gets factually wrong and right about religion generally, and specifically about my own faith tradition.

Spoiler warning: we’ll be going into detail on many specific plot elements and twists. To be clear, this is NOT a true story or, in any way, based on a true story. This is an entirely fictional creation of the writers’ imaginations.

I’ll say right now that Heretic did a pretty good job representing some aspects of Latter-day Saint culture. Sophie Thatcher and Chloe East, the actresses playing the sister missionaries, are former members of the Church themselves, and their background indeed gives some authenticity to their performance.

But there are also some things the film gets factually wrong or which it misrepresents, and in some cases, these hurt the fictional story the filmmakers are trying to tell. There are also arguments against Christianity and against Latter-day Saint beliefs, in particular, that are made by the main antagonist, Mr. Reed, or which are just developed as part of the overall message of the film. Admittedly, these claims would be a lot scarier if they were being forced upon me, personally, by a psychopathic killer. But, after having looked closely at these criticisms while reposing in my safe cushy office chair in broad daylight, my overall conclusion is that these are hardly new ideas and just aren’t very threatening to my faith.

Because I’m going to cover so many topics, a table of contents with links to each section is provided below in case you are looking for something specific. Let’s dive in.

- Costume Design

- A Sexually Explicit Conversation

- Sorority Girls

- Girl Roommate

- Book of Mormon Origin Story

- Butterfly Comment

- Word of Wisdom

- Polygamy Debate

- Reasons for Plural Marriage

- Fanny Alger

- Monopoly and World Religions

- Parallels with Other Gods

- Characterization of God

- All or Nothing

- Choose the Right

- Belief and Disbelief

- Magic Underwear as a Code Word

- Birth Control

- Contrived Miracles

- The True Religion Is Control

- Sexism

- Prayer Is Clinically Disproven

- Conclusion

Reviews of Heretic and Related Content

1. Costume Design

Heretic opens with two sister missionaries dressed in long overcoats and skirts sitting at a park bench. There’s a bit of a dress code for missionaries, and the costume design is quite accurate. You can probably instantly recognize the male missionaries with their shirt, tie, and nametag. Sister missionaries also wear the nametag and are supposed to wear professional-style clothing that reflects their religious purpose in bringing people to Jesus Christ, but which is also practical enough for a lot of walking and biking.

Sisters usually wear blouses, skirts, slacks, sweaters, and low-heel dress shoes. Because of all the walking, their shoes are usually professional-looking, but very practical, nothing flashy or too tall. So the pink sweater, blouse, and skirt combo of Sister Paxton is right on. Same with the black ensemble of Sister Barnes.1

2. A Sexually Explicit Conversation

We don’t get too far at all before there’s something off in Heretic’s portrayal. Literally the first scene of the movie introduces you to an absurd conversation that would likely never happen between sister missionaries. They are sitting on a park bench talking about the size of condoms, male genitalia, and watching amateur pornography.

Now, in the scene, it becomes quickly apparent that this is an awkward conversation that one of the characters, Sister Paxton, regrets even starting. But, seriously, this dialogue just wouldn’t happen. Or, if it ever did, it would be completely out of the ordinary. Sister missionaries just don’t casually talk about sex to each other.2

The other crazy thing is Paxton’s fundamental point. She states that a particular moment in the porno she watched somehow strengthened her faith that humans have souls and therefore that God is real. This seems to be a subtle dig at how Latter-day Saints develop their religious faith, suggesting they can find evidence for God in just about anything, even a porno, no matter how much of a stretch it is.

Not only does this inaccurate portrayal of sister missionaries come across as contrived and unnecessary from a script-writing perspective, but it’s honestly pretty offensive. I’m guessing most Latter-day Saints and people of other Christian faiths would probably agree.

3. Sorority Girls

As the sister missionaries walk through town, a group of sorority girls introduces the audience to the concept of “magic underwear,” which becomes a recurring motif throughout the film. These girls feign interest in the missionaries just to humiliate them by pulling down one of their skirts and filming her undergarments. It is a pretty sexualized exploitation of something Latter-day Saints hold sacred. But, as this topic recurs throughout the movie, it is important to understand what these clothes are.

The so-called magic underwear (sometimes called Mormon underwear or other irreverent nicknames) are what members of the Church refer to as the temple garment. This is a sacred vestment that Latter-day Saints wear who have made covenants with God in the temple. Unlike Catholic priests or Buddhist monks, we don’t display our sacred clothing publicly. Instead, we wear the temple garment as underclothing in our daily lives. We are first authorized to wear it in our sacred temple ceremonies, where it serves as a reminder of Jesus Christ and the promises we have made in the temple to be good, moral people.

While the exact form of these garments has evolved over the years, today they are a simple white undershirt paired with white bottoms. Generally speaking, the clothing we wear should cover the temple garment. We covenant to wear it throughout our lives, except if the activity can’t reasonably be done with the garment on, such as when swimming.3

More on Mormon Garments

4. Girl Roommate

When the sisters finally approach the home of Mr. Reed, they ask him if he has a “girl roommate.” This is sort of a weird term, and Mr. Reed seems confused by it. It left me scratching my head as well. In reality, sister missionaries would usually just ask if there is another adult woman in the home, perhaps the man’s wife if he is married. So “girl roommate” isn’t some sort of insider Latter-day Saint lingo. Even as pairs, missionaries aren’t supposed to be alone with someone of the opposite sex. This is for everyone’s safety and protection, and it goes for both male and female missionaries.4

It’s supposed to be a guard against temptation, violence, sexual abuse, false accusations, and so on. But clearly, rules can’t protect from every possible danger. For this reason, missionary lessons often happen in the homes of members or in a public place like a Church building.

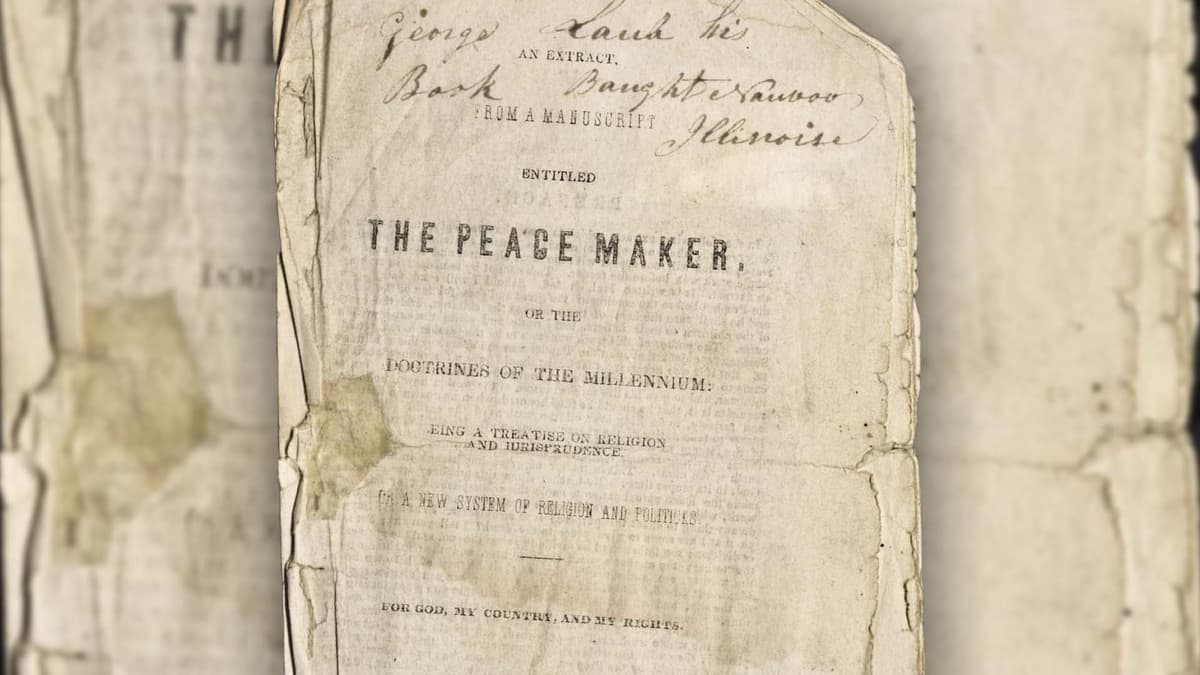

5. Book of Mormon Origin Story

As the sisters sit down in the living room and begin the conversation, Mr. Reed summarizes the origins of the Book of Mormon. He says Joseph Smith was visited by an angel known as Moroni, who showed him where to locate golden plates near his home and also that Smith’s translation of the plates formed the basis of the Book of Mormon. This is a pretty accurate summary of the origin of the Book of Mormon.5

6. Butterfly Comment

During the missionaries’ conversation with Mr. Reed, Sister Paxton says that when she dies, she wants to come back as a butterfly and follow around the people she loves, as a good omen that it’s her. The butterfly is a motif that recurs throughout the film, but the reality is that Latter-day Saints don’t believe in reincarnation or apparitions of animals, so this wouldn’t be a realistic thing for a Latter-day Saint missionary to say. Throughout the film, the butterfly becomes an important symbolic image as well as a philosophical talking point concerning the nature of reality and perception. So, we can probably view Paxton’s strange butterfly comment is a matter of artistic license.

7. Word of Wisdom

At one point in the conversation, Mr. Reed apologizes for offering the missionaries sodas to drink, because, according to him, the Word of Wisdom forbids caffeine and alcohol. Sister Barnes corrects him, pointing out that the commandment doesn’t specifically mention soda. This is accurate. Latter-day Saints adhere to guidelines we call the Word of Wisdom, which outlines some dietary and health standards to live by. It specifically says no tea, coffee, and alcohol.6 But members have interpreted this in different ways, some abstaining from all caffeine, and others not. As a plot element, this sets up Sister Barnes as one who understands the nuances of Latter-day Saint beliefs, foreshadowing the ideological clash with Mr. Reed on more controversial matters.

8. Polygamy Debate

Mr. Reed then starts asking what he calls “awkward questions” and begins to probe them about their feelings around polygamy. Polygamy—or plural marriage, as it is often called within the Church—was practiced by Church members starting with Joseph Smith and ending in various phases in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

It’s a complicated and controversial topic, both from a moral and doctrinal perspective, and historians are still trying to unravel all of the details. But ultimately, it hearkens back to the biblical practice when Abraham and Jacob took on multiple wives to fulfill God’s covenant promises. Latter-day Saints believe that God commanded this practice for a few core reasons: (1) to restore an ancient, divinely-instituted practice, (2) to raise up a righteous generation of saints, and (3) to act as a type of trial, testing the faith and commitment of early Church members.

The sister missionaries become uncomfortable with the topic, which isn’t particularly uncommon. This isn’t an aspect of Church history that most missionaries or members of the Church know a lot about, especially since the Church hasn’t practiced it for more than a century. Mr. Reed is clearly exploiting an issue that he knows they likely aren’t prepared to handle.7

9. Reasons for Plural Marriage

When asked about polygamy, Sister Barnes gives her understanding of the issue, which is that it was a spiritual mission or priority mandated by God, but that it also was needed to increase the membership of the Church. There were actually multiple reasons for this practice taught in the scriptures and by Joseph Smith. The need to raise up a righteous generation of Saints was just one of them. Others include plural marriage being part of what’s called the “restitution of all things” and also functioning as a type of Abrahamic test or trial. Those are the most authoritative reasons from scripture and Joseph Smith. All others are more speculative, and there’s still a lot we don’t know about plural marriage.8

10. Fanny Alger

As part of the polygamy discussion, Mr. Reed brings up Fanny Alger, who many historians believe was Joseph Smith’s first plural wife. Mr. Reed’s fundamental claim is that Joseph Smith’s revelation about plural marriage was merely a convenient way to get free sex. He uses the Fanny Alger episode to try and prove his point. The history is admittedly complicated and fragmentary, but some of the most knowledgeable experts on Joseph Smith’s practice of plural marriage have reached very a different conclusion from Mr. Reed. Don Bradley, for instance, has concluded that Joseph Smith’s behavior was consistent with his religious claims.9

Since no one can historically prove or disprove whether Joseph Smith’s practice of plural marriage was directed by God, this is indeed ultimately a matter of faith. But a strong historical case can and has been made for Joseph Smith’s sincerity. He clearly didn’t implement polygamy merely for free sex. That type of narrow, cynical view can’t account for a significant amount of the historical data.10

More on Mormon Polygamy

11. Monopoly and World Religions

Mr. Reed attempts to build an argument that all religions are just copycats of each other and none are inherently true. He develops this reasoning by showcasing historical iterations of the board game Monopoly. He then claims that Mormonism is the zany regional spin-off edition (while the screen shows him placing a Bob Ross version of monopoly on the table, with Ross’s recognizable big hair and paintbrush).

Using object lessons is a very “Mormon” thing to do and is frequently used by missionaries. So, this seems to almost be an ironic reversal of that practice, as Reed uses it to deconvert rather than convert. Honestly, it’s an amusing comparison and I’m not really offended by it. But this is also just an analogy. It’s not an actual argument for direct religious dependence or derivation. Sister Barnes mockingly refers to it later on as a “garage sale board game metaphor.”

12. Parallels with Other Gods

In developing his claim that Jesus was a mere ideological construct, Mr. Reed argues that Jesus was part and parcel of a broader mythology which was common for thousands of years among various ancient cultures. To drive home his point, Reed utilizes artistic depictions of gods from various ancient cultures. Reed doesn’t get very deep into the weeds, but the parallels he highlights between Jesus and these other religious figures is clearly unsettling to the sister missionaries.

What most viewers probably won’t know is that Reed is just rattling off some common anti-Christian talking points that have been debated all over the internet for decades. There certainly are some parallels between Jesus and gods in other religions, but many of them, on closer inspection, just aren’t that impressive. For instance, Mr. Reed claims that, just like Jesus, many other gods were born on December 25. Even if that were true, it hardly matters. This is because the dating of Christ’s own birth isn’t even known and has long been debated by scholars.11

Reed also claims that the Egyptian god Horus was crucified, had 12 disciples, was resurrected on the third day, and so on. Yet, none of these claims accurately reflect the mythology surrounding Horus. Among possible sources, these ideas may be coming from a 2009 book on Horus and Jesus.12 However, this is the type of source that real scholars of Christianity dismiss. As stated by the prominent agnostic New Testament scholar Bart Ehrman, “Mythicists of this ilk should not be surprised that their views are not taken seriously by real scholars, that their books are not viewed in scholarly journals, mentioned by experts in the field, or even read by them.”13

Ultimately, while the quick barrage of claims made by Reed might seem impressive at first, they are actually pretty flimsy once you get down into the details. As the more cerebral of the two missionaries, Sister Barnes picks up on this and even points to some of the flaws in Reed’s argument, including the fact that Reed wasn’t accounting for the significant differences between Jesus and these other figures.

The funny thing is, Latter-day Saints don’t actually oppose Mr. Reed’s overarching point. We believe many ancient religions echo the original truths that God established in the beginning of creation and dispersed throughout the earth over time. From our perspective, Christianity, and more specifically the Restored Church of Jesus Christ, contains the fullness of God’s gospel, but we wouldn’t reject parallels from other religions. Most of the ones presented in Heretic are just factually incorrect and make a weak case for direct derivation.

13. Characterization of God

Mr. Reed concludes his argument by claiming that “If God is real, and he’s watching us when we masturbate, and has such a fragile ego that he only helps us when we beg him, and flatter him with praise, and he hates gay people for being who he made them to be … then that is terrifying.”

This is definitely a negative twist to the traditional Latter-day Saint view of God. Yes, God is always aware of us and our mistakes. But, no, he doesn’t have a fragile ego. Nor does he only help us when we beg or praise him. As Jesus himself taught, God makes the “sun to rise on the evil and on the good, and sendeth rain on the just and on the unjust” (Matthew 5:45). Yes, we believe that God has prohibited homosexual behavior, but, no, God certainly doesn’t hate gay people. In fact, we affirm that God loves all of His children equally.14

Obviously, not everyone’s going to agree with Latter-day Saint beliefs about God and his moral expectations, but what Mr. Reed offers is really just a twisted caricature of the God we actually worship.

14. All or Nothing

As a rhetorical strategy, Mr. Reed at one point reads off a statement made by former Church President Gordon B. Hinckley: “either the Church is true, or it is a fraud. There is no middle ground.”15 This establishes a prophetic source of information that the sisters wouldn’t reasonably be able to disagree with. And, indeed, most members of the Church hold this view. For the institution to be legitimate, its core religious claims logically need to be true. If they aren’t, then Joseph Smith must have been either deluded or a fraud.

But then Reed goes even farther, giving his own subtle spin on the idea, claiming, “It is either all true. Or none of it is true.” The distinction may seem small, but it is actually quite significant. Latter-day Saints don’t believe that everything within the Church—every minute detail of protocol, culture, and policy—needs to be infallible or 100% true for the Church, as a divinely established institution, to be collectively true or legitimate in God’s eyes. Not all aspects of the Church are equal, and some of its claims are much more fundamental and official than others. Mr. Reed’s all-or-nothing version of the claim implies that even the most minor discrepancy or flaw would render the entire Church as false. That’s not what President Hinckley said, nor is it what Latter-day Saints believe.

15. Choose the Right

When choosing which door to go through as part of Mr. Reed’s twisted game, Sister Paxton, trying to sound conversational and friendly in a dangerous moment, jokes about how they should choose the right door because “choose the right” is something taught in primary. This is totally accurate.16 “Choose The Right” is a simple slogan we learn as children to communicate how we should make moral choices. And, yes, it’s frequently used as a joke when choosing between directional right and left.

16. Belief and Disbelief

After looking at the doors labeled as BELIEF and DISBELIEF, Sister Barnes declares, “But both doors lead to the same place, don’t they?” This seems to be a major thesis in Mr. Reed’s argument. Verbally, he emphasizes just how important the choice is, but the very architecture of his home suggests he, or perhaps the filmmakers, don’t actually believe what he is saying. It seems the missionaries are intended to reach the point that Barnes eventually does—which is that the choice really doesn’t matter. Whether that is because, as Reed argues, belief and disbelief are equally terrifying or because the truth just doesn’t matter isn’t fully unclear.

While this ambiguity may work well as an element to ratchet up suspense, there are problems with viewing religious choice as meaningless or an illusion. For one thing, a number of social studies suggest that, whether true or not, religious belief and practice have significant benefits.17 More than that, not all outcomes of faith may be easily discernable in this life. If the fundamental tenets of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints are true, then the choice of belief has significant temporal and eternal consequences.

17. Magic Underwear as a Code Word

When trying to find a way to thwart Mr. Reed, Sister Barnes comes up with the term “magic underwear” as a codeword. This, of course, relates back to their encounter with the sorority girls earlier in the film. This word comes into play again near the film’s climax. After descending into the basement and passing through a series of doors—almost a perverse inversion of Latter-day Saint temple architecture—Sister Paxton eventually reaches a blocked path, where Mr. Reed catches up to her. Just before he seems about to attack her, he inadvertently says the code word “magic underwear,” upon which she stabs him in the throat, just as Sister Barnes had previously planned.

The use of this codeword at this juncture is perhaps, a subtle mockery of the key words that are used at a certain point in Latter-day Saint temple ceremonies.18 It also just gives the filmmakers a chance to focus again on the “magic underwear” label, which, again, depicts Latter-day Saints as weird or eccentric.

18. Birth Control

At one point in the film, there’s a disagreement between Mr. Reed and Sister Paxton about an implant found in Sister Barnes’s arm. Mr. Reed claims the device is a sign that Sister Barnes was just a simulation of a real person. Sister Paxton, on the other hand, concludes it is just a contraceptive. In response to her theory, Reed asks if she’s ever met a Mormon missionary who was on birth control. Paxton admits she hasn’t but argues that Sister Barnes wouldn’t have mentioned it. This is because, as Paxton claims, “Our church would’ve made her feel ashamed about it. And she would’ve been too embarrassed.”

In my experience, this just isn’t accurate. It’s true that, like many other Christian religions, leaders of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints disapproved of birth control in the past.19 But today the Church has no formal doctrine or policy prohibiting or discouraging the use of contraceptives, and many Latter-day Saint women use birth control as treatment for acne, endometriosis, and PCOS. Many married Latter-day Saint couples also use birth control. Admittedly, this might be a private or easily misunderstood issue, and therefore not discussed publicly very often. But Paxton’s claim that the Church, specifically, would have made Sister Barnes feel embarrassed seems pretty unwarranted.20

Can Mormons Use Birth Control

19. Contrived Miracles

Mr. Reed can be seen as playing two roles or functions within the film. At first, he seems to be a vehicle for attacking Christianity and Latter-day Saint beliefs in particular. He’s given a lot of time to make arguments and air his anti-religious sentiments. Yet, as the show goes on, Reed himself seems to become a metaphor for everything he sees is wrong with religion. The control, manipulation, sexism, and so on. He even forces the sister missionaries to become witnesses of a contrived miracle, which is all part of his elaborate scheme.

There may be a subtext here that is worth exploring. Many critics of the Church view Joseph Smith as a manipulative con artist who developed an elaborate plan to trick witnesses into believing his contrived miracles. Thus, Reed’s paradigm can be viewed as just a new iterative religion, an outgrowth that mirrors all the supposed horror and evil of those that came before him, and which makes a sinister mockery of Joseph Smith and his founding religious claims. As the sister missionaries naturally rebel against Reed’s psychotic machinations and see through his flimsy religious hoax, they are, perhaps, meant to recognize the evil and fallibility at the very heart of their own religion.

Or perhaps not. It’s always hard to tell what the writers of a film intended. But this does seem like a plausible interpretation. If so, it is once again bad form. Mr. Reed is really nothing like Joseph Smith, and their religious accomplishments, miraculous claims, and moral character are miles apart.21 I really hope this parallel wasn’t intended by the filmmakers.

20. The True Religion Is Control

The film seems to suggest that while most religions don’t overtly coerce their followers into submission, they manipulate their members with the illusion of choice to subconsciously mold the members to their will. Mr. Reed argues that the reason he is locking up women in his basement is the same reason that the Mormon Church hands out bibles after a hurricane. It’s easier to control people who have lost everything. The punchline of Reed’s whole philosophy—the big revelation that he wants the sister missionaries to accept—is that “the one true religion is … control.”

If you already believe religion is fundamentally manipulative, I’m probably not going to change your mind anytime soon. But I think it’s worth considering a key difference between Reed’s approach and that of many religions. Mr. Reed is manipulating his victims’ choices through fear, abuse, and violence. In contrast, when The Church of Jesus Christ provides relief for natural disasters, they don’t first hand out bibles. Instead, they usually stay focused on disaster clean-up and humanitarian aid.22

Furthermore, the message the Church tries to offer is truly one of hope. And in so many cases, the Church delivers on that message. “People who are active in religious congregations tend to be happier and more civically engaged” than non-religious individuals.23 I know I’ve personally found joy and meaning in this lifestyle, and I’ve never experienced anything like the abuse Mr. Reed inflicts on his victims.

21. Sexism

On several occasions, Mr. Reed argues or implies that religion is a misogynistic scam, where women are controlled by men, even down to their underwear. As a woman in Christ’s restored Church, I personally reject the notion that every aspect of my life is systemically and maliciously controlled by men.

You may not come to the same conclusion as me, but I’ve felt empowered through my participation in my faith. I don’t consume mind-impairing substances. I am granted priesthood power through my temple worship. And I have a divine destiny to become like God one day. All of these things have given me clarity, power, purpose, and meaning to steer my life in a way to become my best self. And yes, it involves men. My Church has a fairly unique belief that men and women need each other reciprocally to become more like God. I love belonging to a religion where women are not appendages or an afterthought, but are necessary and even central to God’s plan.

22. Prayer Is Clinically Disproven

As Sister Paxton and Mr. Reed sit struggling for life in the basement, suffering from their mutually inflicted wounds, she cites what she sees as clinical proof that prayer doesn’t work. This comes from the 2002 Study of the Therapeutic Effects of Intercessory Prayer. That study did indeed find that a group of patients who received prayers on their behalf did not have significantly improved health outcomes compared to those that didn’t.24 But inferring from this data that prayer just “doesn’t work” is a pretty big leap of faith itself. While prayers may at times result in miraculous recoveries or improved health, the effects of prayer, as understood by Latter-day Saints, are often more spiritual than physical.

There are also many different variables, including faith, righteousness, timing, and especially God’s will that may all influence outcomes. So, at the outset, it should be pretty clear that the Latter-day Saint view of prayer isn’t something that could be reliably assessed in any type of clinical study. We don’t believe group prayers ascend up into some type of heavenly vending machine which automatically churns out the desired blessings.25 That being the case, I’m not very surprised by the results of the study.

23. Conclusion

Overall, Heretic offers an intense ideological contest between belief and disbelief. It seems that the ending was left intentionally ambiguous, leaving room for either faith or doubt. Yet, on more subtle rhetorical levels, one gets the feeling that the filmmakers are constantly trying to nudge audience members towards a negative view of religion. As for its portrayal of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, in particular, I felt the film’s inaccuracies were often as unnecessary as they were unfortunate. Some things it gets right, but many others were obvious flubs.

I can also see how the film could be faith-damaging to some viewers. Mr. Reed is certainly charming, and the film gives him an intimidating veneer of intellectual prowess. This was unsettling to the missionaries, and it could be for some religious audience members as well. But when you actually slow down and look at Reed’s claims, they hardly come across as having been produced by someone with a genius-level IQ. In reality, they are generally weak, amateurish, cynical, and uninformed.

Perhaps that was intended by the filmmakers, or maybe that was just the extent of their own polemical understanding. Whatever the case, Mr. Reed’s inflated view of his own arguments may actually be one of the more accurate depictions of the film, as it reflects well the average anti-Mormon attacks against my faith.

From a pure storytelling perspective, it’s still unclear to me what the point of the whole ruse was, or how it all came together. Did Mr. Reed start his cult just to make this demonstration to the missionaries? How did he lure or manipulate the women he trapped in his basement? Who were these women, where did they come from, and how did he get them to participate in his cult? These and other questions are left unanswered. Also, besides just sadism, there doesn’t seem to be a purpose to the deconstruction. Especially near the end, the fast pace and suspense mask significant plot holes and incoherent sequences of events.

There’s also a level of disturbing irony in the fact that, despite Mr. Reed being the villain of the film, many viewers may walk away agreeing with him. To some extent, it seems like the audience is being invited to root for the survival of the naïve missionaries, but agree with the worldview of the mansplaining psychopath. I would consider this problematic since, despite paying lip service to the evils of misogyny, it subtly glorifies the intellectual, emotional, and physical abuse of religious women in the name of “debunking” their supposedly naïve religious worldview.

Some may say Reed is just a proxy for the evil religious traditions who do the real damage, but The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is not caging emaciated women and psychologically violating them until slaughtering them. Male, atheist filmmakers with an apparent agenda of religious deconstruction are the ones entertaining these fantasies.

Sadly, this kind of semi-glorification of exploiting and abusing Latter-day Saint women may have unfortunate real-life consequences. I hope and pray that’s not true, but the film is flirting with some dangerous messaging. As Church spokesman Doug Andersen put it, “Any narrative that promotes violence against women because of their faith or undermines the contributions of volunteers runs counter to the safety and well-being of our communities.”26

This is not a film I would particularly recommend if you’re looking for something that portrays a religious minority with integrity. But maybe, for the sake of pure thrill and suspense, this is something one could enjoy as long as you take all its religious claims and depictions with a grain of salt.

- 1. See “Guidelines for Sisters,” online at churchofjesuschrist.org.

- 2. For the standards of sexual morality that sister missionaries would have been taught, see “Your Body Is Sacred,” in For the Strength of Youth: A Guide for Making Choices, online at churchofjesuschrist.org.

- 3. See “Sacred Temple Clothing,” online a churchofjesuschrist.org.

- 4. See Missionary Standards for Disciples of Jesus Christ (3.5.1), online at churchofjesuschrist.org.

- 5. For a helpful scholarly resource, see Dennis L. Largey, Andrew H. Hedges, John Hilton III, and Kerry M. Hull, eds., The Coming Forth of the Book of Mormon: A Marvelous Work and a Wonder (BYU Religious Studies Center; Deseret Book, 2015).

- 6. See “Word of Wisdom,” online at churchofjesuschrist.org.

- 7. For an in-depth treatment of polygamy from a faithful Latter-day Saint historian, see Brian C. Hales, Joseph Smith’s Polygamy: History and Theology, 3 vols. (Greg Kofford Books, 2013). See also, https://josephsmithspolygamy.org/.

- 8. For an in-depth treatment of polygamy from a faithful Latter-day Saint historian, see Brian C. Hales, Joseph Smith’s Polygamy: History and Theology, 3 vols. (Greg Kofford Books, 2013). See also, https://josephsmithspolygamy.org/.

- 9. See Don Bradley, “Knowing Brother Joseph: How the Historical Record Demonstrates the Prophet’s Religious Sincerity,” 2023 FAIR Conference, online at churchofjesuschrist.org.

- 10. Bradley explains, “Clearly on so many levels, Joseph Smith is sincere and the larger pattern—where we map out the pattern of tens of thousands of actions and speech events in his life—the more clear it becomes to me that Joseph Smith was religiously sincere. He believes in what he’s teaching. He believes that God has called him as a prophet and is speaking through him.” Don Bradley, “Knowing Brother Joseph: How the Historical Record Demonstrates the Prophet’s Religious Sincerity,” 2023 FAIR Conference, online at churchofjesuschrist.org.

- 11. See Scripture Central, “How Does the Book of Mormon Help Date the First Christmas? (3 Nephi 1:13),” Knowhy 255 (August 20, 2019).

- 12. See D. M. Murdock, Christ in Egypt: The Horus-Jesus Connection (Stellar House Publishing, 2009).

- 13. Bart D. Ehrman, Did Jesus Exist? Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth (HarperOne, 2012).

- 14. See “Same-Sex Attraction,” online at churchofjesuschrist.org.

- 15. Gordon B. Hinckley, “Loyalty,” General Conference, April 2003, online at churchofjesuschrist.org.

- 16. See “Choose the Right,” online at churchofjesuschrist.org.

- 17. https://www.lightandtruthletter.org/letter/fruits-of-the-church

- 18. Brigham Young famously taught, “Let me give you the definition in brief. Your endowment is, to receive all those ordinances in the House of the Lord, which are necessary for you, after you have departed this life, to enable you to walk back to the presence of the Father, passing the angels who stand as sentinels, being enabled to give them the key words, the signs and tokens, pertaining to the Holy Priesthood, and gain your eternal exaltation in spite of earth and hell.” Brigham Young, "Necessity of Building Temples-The Endowment," April 6, 1853, Journal of Discourses, 26 vols. (Liverpool : F. D. Richards, 1855), 2:31.

- 19. See “Christian views on birth control,” online at wikipedia.org.

- 20. See “Birth Control,” online at churchofjesuschrist.org.

- 21. See Scripture Central, “How Can We Know What to Believe about Joseph Smith’s Personal Character? (3 Nephi 8:1),” Knowhy 413 (August 20, 2019).

- 22. See, for instance, “How the Church Organizes Before and After Disasters to Provide a Helping Hand,” Newsroom, October 19, 2020, online at newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org.

- 23. “Religion’s Relationship to Happiness, Civic Engagement and Health Around the World,” Pew Research Center, January 31, 2019, online at pewresearch.org.

- 24. See Jeffery A. Dusek, et al., “Study of the Therapeutic Effects of Intercessory Prayer (STEP): study design and research methods,” American Heart Journal 143, no. 4 (2002): 577–584.

- 25. See D. Todd Christofferson, “Our Relationship with God,” General Conference, April 2022, online at churchofjesuschrist.org.

- 26. See Sean P. Means, “Makers of ‘Heretic’ say their thriller breaks stereotypes about Latter-day Saint missionaries,” The Salt Lake Tribune, November 4, 2002, online at sltrib.com.

.jpeg)