Magazine

A Remarkable Vision

Title

A Remarkable Vision

Magazine

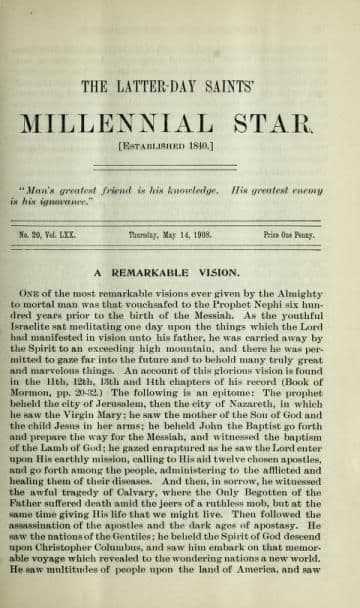

The Latter Day Saints' Millennial Star

Publication Type

Magazine Article

Year of Publication

1908

Editors

Penrose, Charles W. (Secondary)

Pagination

305–311

Date Published

14 May 1908

Volume

70

Issue Number

20

Abstract

In part of his vision recorded in the Book of Mormon, Nephi saw Columbus who would discover the New World (1 Nephi 13:12-13).

A REMARKABLE VISION.

One of the most remarkable visions ever given by the Almighty to mortal man was that vouchsafed to the Prophet Nephi six hundred years prior to the birth of the Messiah. As the youthful Israelite sat meditating one day upon the things which the Lord had manifested in vision unto his father, he was carried away by the Spirit to an exceeding high mountain, and there he was permitted to gaze far into the future and to behold many truly great and marvelous things. An account of this glorious vision is found in the 11th, 12th, 13th and 14th chapters of his record (Book of Mormon, pp. 20-32.) The following is an epitome: The prophet beheld the city of Jerusalem, then the city of Nazareth, in which he saw the Virgin Mary; he saw the mother of the Son of God and the child Jesus in her arms; he beheld John the Baptist go forth and prepare the way for the Messiah, and witnessed the baptism of the Lamb of God; he gazed enraptured as he saw the Lord enter upon His earthly mission, calling to His aid twelve chosen apostles, and go forth among the people, administering to the afflicted and healing them of their diseases. And then, in sorrow, he witnessed the awful tragedy of Calvary, where the Only Begotten of the Father suffered death amid the jeers of a ruthless mob, but at the same time giving His life that we might live. Then followed the assassination of the apostles and the dark ages of apostasy. He saw the nations of the Gentiles; he beheld the Spirit of God descend upon Christopher Columbus, and saw him embark on that memorable voyage which revealed to the wondering nations a new world. He saw multitudes of people upon the land of America, and saw the remnant of his seed and the seed of his brethren (the American Indians) driven before them and scattered. And finally he saw the dawning of a brighter era, the restoration of the everlasting gospel, in all its fulness and pristine power and authority, and men sent forth to proclaim it, first to the Gentiles and afterward to the Jews. Not one jot or tittle of this remarkable vision has been left unfulfilled, but every event foreshadowed by the prophet has literally come to pass.

To one of these events we wish now to call the attention of our readers. In describing the things which he saw in his vision, Nephi said:

“And I looked and beheld a man among the Gentiles who was separated from the seed of my brethren by the many waters; and I beheld the Spirit of God, that it came down and wrought upon the man; and he went forth upon the many waters, even unto the seed of my brethren, who were in the promised land.

“And it came to pass that I beheld the Spirit of God, that it wrought upon other Gentiles; and they went forth out of captivity, upon the many waters.

“And it came to pass that I beheld many multitudes of the Gentiles upon the land of promise; and I beheld the wrath of God, that it was upon the seed of my brethren; and they were scattered before the Gentiles and were smitten.”

If Nephi had written his account of the events after they had taken place, instead of hundreds of years before, he could not have described them move accurately. The readers of the Star are, no doubt, familiar with the story of Columbus, but the following extracts from a graphic account of the discovery of America by that Divinely-appointed navigator will be read with renewed interest. The article is from the pen of Walter Wood, and appears in the current number of that popular magazine, Pearson’s:

“Sunrise at Palos, a Spanish port not far from Cadiz, on August 3rd, 1492; and a tiny squadron of old-world ships putting slowly to sea, with a fair wind, steering west, where wise men and adventurous mariners say there is a New World. The vessels are the Santa Maria of a hundred tons, the Pinta of fifty, and the Nina of forty. In all they carry eighty-seven officers and men. Fifty-two are in the flagship, which is the Santa Maria, and the chief of them all is the man they call Admiral, who is Christopher Columbus, an Italian of Genoa, who has so far satisfied the King and Queen of Spain that there is a land of gold across the Western Ocean that they have ordered Palos to find and furnish ships and men to carry out a voyage of discovery. This is the expedition which is starting at sunrise, and which at the end of many tribulations is to be crowned by the discovery of America.

“The start was a brave and hopeful one, yet no sooner were the ships out of sight of land than some of the people in them weepingly implored Columbus to return. He steadfastly refused and bade them remember their duty and their vows. And were they not, he asked, journeying to a region which was rich beyond the dreams of even the greediest amongst them? He struck the right note at the outset, and found that this appeal to their avarice was successful when all others failed.

“Imagination must be brought to bear to picture the state of things at sea in those days, because there is but scant material concerning the actual life on board and the ships themselves. But we do know that our picture will not be overdrawn when we say that the little vessels of Columbus were what we should look upon as floating hells. They were clumsy, small, ill-equipped, poorly found, and bad-weather craft. ‘She could carry no sail,’ reported Columbus of one of them, ‘and her side would lie almost under water.’ They were enormously top-heavy, and the accommodation for the officers and crew was out of all proportion to the relative ranks. Those were the days when everything was done for the person of importance, and nothing for the humble individual. The stern was built high principally that the officers might have plenty of living room; as for the rest of the adventurers, they were huddled together anyhow and anywhere. There were no known methods of preserving either liquid or solid food, and both were rank and foul soon after leaving port. The biscuits were so full of weevils that some of the men, rough and hardened though they were and far from fastidious, waited till it was night, so that they could not see what they were eating. And not only did the provisions go bad, but often they gave out, and atone time, when Columbus—this was on his second voyage home— was returning to Spain with thirty Indians in his ships as trophies and examples from the New World, he was urged to destroy them, so that his own people might live.

“The rains came as welcome helps, the fresh water replacing the unwholesome stuff with which the vessels had been furnished at the start, while occasionally a fish or bird would give a greatly needed change of food. Even sharks were welcome fare. * * * With his crazy little ships manned by superstitious, fearful, discontented and mutinous crews, Columbus struck out into the vast unknown. The voyagers went comforted and encouraged by the prayers of the priests and the people, few of whom believed that the Admiral and his comrades would ever return. The Canary Islands, not very many leagues away, were known territory, and towards them the little fleet was steered.

“Even at the outset treachery and terror triumphed, for the rudder of the Pinta became useless in such a way as to suggest that there had been tampering with it, so that the ship would be compelled to return to port. The damage was repaired, but the rudder broke loose again. If the wrongdoers supposed that Columbus was the man to turn back from the task upon which he had set his heart, they saw their error at the outset. Nothing daunted him, and resolute in his purpose he held on until the Islands were reached. That was in nine days, a good run with such ships, and considering the crude navigation of the age. Today the swiftest Cunarder will cross and re-cross the Atlantic in the same time. Columbus made his damage good, and on September 6th resumed his voyage. Now, if ever, his courage and fortitude were needed, and neither deserted him. He steeled his heart as he steered towards the awesome and mysterious West.

“Day after day the clumsy vessels blundered on, with the everlasting sea and sky for company, and the monotony of the depressing ocean gripping every soul. There was the known land behind them; there was the unknown, undiscovered world which might be somewhere in the distant dim ahead. There were the home ties, the friends, the green fields, the towering hills, the blue skies, and the glorious sunshine ever present in the minds of the adventurers, to make them all the more precious by comparison with the ruthless waters and the gloomy heavens of the stormiest ocean in the world. There was the gnawing of homesickness at the heart, and from day to day the terrible illnesses which came at sea from the rotting food and drink that were carried in such primitive fashion. And more depressing still, the shadow of death—for there were those who could not survive the hardships of the undertaking, and were cast into the sad waters. So excessive were the sufferings, so hopeless was the prospect of ultimate success, that the marvel is that Columbus ever crossed the Western Ocean at all, and was not destroyed by those disaffected mariners who swore they would not go farther with him, and that if he was resolved on self-destruction he should not, at any rate, sacrifice their lives with his.

“Columbus saw his danger, and grappled with it successfully. He understood human nature, and when appeals to the reason and loyalty of his followers failed, he did not hesitate to pander to their avariciousness. Men will do much for gold, and the people of Columbus listened greedily to his repeated assurances that the day would soon dawn when they would behold the New World, and enjoy its riches and countless pleasures.

“The long days passed slowly, with only one thing to look forward to—the ending of the voyage, either by discovering the New World or going back home. The latter thing was that for which nearly all men craved, and there were sinister whisperings that Columbus was seeking not the advancement of his Royal master’s kingdom, or the Kingdom of Christ, both of which he claimed to be the objects of his undertaking, but his own personal glory and advancement. Whisperings turned to open complaints and appeals, and then to actual threats. Still Columbus remained unmoved; still he swore that he would carry on to the end, and never relinquish his purpose.

“When threats failed, the malcontents went so far as to plot his destruction. But Columbus was as little moved by threats of bodily ill as he had been by fears and terrors in his followers. He resisted and defied them all, and by sheer courage and tenacity he kept up the spirits of his crews until the day came when sea and air gave evidence that land was very near. The whole life of the adventurer was cast on the hazard of a die, and because he had this tenacity of purpose he triumphed. It was in keeping with the fitness of things that the admiral himself should be the first to prove that his faith was justified, for it was Columbus who first saw the New World, and he was the first European to set foot on its marvelous shores.

“Days had passed into weeks, and the weeks into the third month after leaving home, when Columbus, watching from the window of his poop cabin, looking with longing eyes over that lonely waste of waters which he had traversed for seventy days, saw in the distance what looked like a twinkling star. Yet he knew that it could not be a star, because the light moved to and fro, and sometimes disappeared completely. His heart beat rapidly with hope, but fearful that his eyes, so often deceived in these strange seas, had once more played him false, he called two men to look also. One obeyed, and vowed that he beheld the light; the other was too late. But Columbus knew in his heart that he was not deceived; it was a light of some sort on the land, and when the day broke after a long night of agonised suspense, a shore, indeed, was seen, and the air resounded with the exulting cries of those who saw land when they had almost reckoned themselves as lost. A reward had been promised to him who soonest saw the New World, and it was given to Columbus, ‘because he had been the first to see light in the midst of darkness.’

“Columbus had reached the Bahamas, the most northerly group of the West Indies. Like magic, the weary sea had given place to luxuriant vegetation, delightful streams, and everything that could gladden hopeless sailors. As the sun rose above the horizon a solemn Te Deum was chanted, and the boats, having been manned, the adventurers went ashore in pomp and splendour, with music playing and banners flying. The beach was crowded with marveling Indians, who, for the first time, saw the ships and the white men who heralded the birth of a New World. The natives were naked, and stared astonished at the clothed and armed foreigners who had landed from three ships—ships which in themselves were wondrous curiosities in a region where such vessels had never before been seen.

“Unconscious of disasters that were to follow, and of the evils which were iu store for himself, full only of the joy of a great victory, Columbus made ready to return and report to the King and Queen of Spain that he had in very truth discovered a New World beyond the seas, a world of which part had been already added by himself to his Sovereign’s kingdom, and was now held by a little garrison that had been left behind. But he did not start homeward until he had found other islands, and assured himself that the new realm must be of vast extent. To his first-found island, which the Indians called Guanahani, and which is now Watling Island, he had given the name of San Salvador, ‘In remembrance of that Almighty Power which had so miraculously bestowed them.’

“On January 4th, 1493, the homeward voyage began. This meant that in the very heart of winter the adventurers were to cross the wild Atlantic, and in vessels, too, that were worm-eaten, rotting, and in worse repair than ever. The gales of the Western Ocean thrashed and smashed them, and in the turmoil the ships parted. This was a prelude to the buffetings with which Columbus made such close acquaintance in his four voyages of discovery to America.

“Time after time in his venturesome undertakings he encountered dangerous weather, with such anxious hours as when he was ‘running without a rag of cloth. It was a mighty sea, with high winds and frightful thunder.’ Think of it, ye who do not care to look upon a gale, even from the safe and cosy corner of a giant liner’s smoke-room. At another time—to show the difficulties he surmounted—he strove for sixty days in the Gulf Stream to get to a certain spot on which he had set his heart, and strove in defiance of weather which was so bad that it looked, to these simple seamen, as if the end of the world had come. Columbus himself was sick almost unto death; still, he had a cabin made on the deck, so that he could guide his ship and cheer his crew. During the whole of the sixty days he did not advance more than seventy leagues. Such was the man who at last, weather-worn and weary, but triumphant still, reached Palos on March 15th, 1493, having been absent on his first momentous voyage for more than seven months.

“The bar had been crossed and the anchor dropped, and the people were still mad with wonder and excitement, when another sail was seen. Almost instantly it was known that this was the missing Pinta, and so it proved. Pinzon, too, brave and enduring mariner, had safely crossed the ocean. Then a strange and in its way a tragic thing occurred. The subordinate believed and hoped that the master had perished, and that he himself would be the first to reach home with the tidings of the great discovery, and the one to receive the honors for the finding. He saw that Columbus had come—and forthwith went away, shut himself up, and died, chiefly, it is said, of disappointment.

“Columbus in six months was again steering west, having been honored, petted, fawned upon, and feted by all classes. He had left a garrison in the New World, and he rejoined it after crossing the Western Ocean for the third time. Whatever dreams he had enjoyed of the founding of a peaceful kingdom were destroyed at once. The garrison had vanished, the fort was ruined—and he learnt that his little band had gone in quest of the gold for which all men craved. They had quarreled with the Indians, too, and here and there their dead bodies were discovered, to tell the sorry story of unfaithfulness and doom.

“Disaster followed disaster in that brilliant and fatal country, and although he made further explorations and added to his monarch’s kingdom, Columbus saw that he was in danger of a grievous fall. The scum of the earth had been attracted to the West, and enemies set to work to discredit him and belittle his achievements. The stories were told at home, and so readily and thoroughly believed, that a Spanish dignitary was sent out to inquire into them. He went, and believing what he heard, used bis great powers to the extent of having Columbus put in irons and sent on board ship to be carried back to Spain.

“All the way across the Atlantic the man who had found the New World, who had crossed the ocean as a conqueror, and recrossed it as a favorite of royalty, was now conveyed as an ignoble prisoner.

“For a little while at least he was restored to favor when he reached Spain again; but it was not until 1502 that he set forth on his last expedition to the West. He had four decaying and worthless little ships, while he himself was old beyond his years, and broken in spirit and shattered in hopes. Columbus added to his discoveries again, and increased the sources of his master’s revenue. But there were too many clamoring for the wealth of the Indies to allow of him who had been the means of finding it receiving his proper share.

“The neglect which was harder to bear than enmity befell him, and he prepared to bid farewell to ‘this rough and weary world,’ as he sadly called it. ‘I have done all I could,’ he declared resignedly, ‘and I leave the rest to God.’

“Afflicted with poverty, worn out in body, crushed in spirit, and overcome with despair, knowing that even his royal master was false to him, but still full of faith in his Redeemer and of hope for his future life, he went to Valladolid, where, at a cheap inn, he died May 21st, 1506, which was Ascension Day. In that city he was buried, but six years later he was re-interred at Seville, where the King, who had neglected him, had a costly tomb erected to his memory, with an inscription saying that to Spain he had given a New World. A quarter of a century later the remains were taken across the Atlantic to San Domingo, and two and a half centuries afterwards—in 1795—Columbus, or the bones of him, as they were supposed to be, were placed in the cathedral at Havana, Cuba. When that island was conquered by America, the box which held the reputed bones was conveyed to Seville, and there it rests, though no man can say with sureness that these poor relics are the fragments of Columbus.”

Subject Keywords

Bibliographic Citation

Terms of use

Items in the BMC Archive are made publicly available for non-commercial, private use. Inclusion within the BMC Archive does not imply endorsement. Items do not represent the official views of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or of Book of Mormon Central.