Book

20 Chapters

Noel B. Reynolds

Noel B. Reynolds is professor of political science at Brigham Young University and president of the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies.

For most Latter-day Saints, the question of Book of Mormon authorship is noncontroversial. Within the devout LDS community , few doubts are raised about the truthfulness of accounts given by Joseph Smith, the Book of Mormon witnesses, and various family members and scribes associated with the process by which the Book of Mormon came forth . Gold plates containing a thousand-year record of the ancient Nephites were delivered to Joseph by Moroni, the last custodian of that record and now an angel of God. Joseph translated the record by supernatural means and the aid of several scribes. For Latter-day Saints, the Book of Mormon is revealed scripture, written by prophets and brought forth in our day by miraculous means to provide the world with a touchstone by which they might measure the truth of the restored gospel and its importance in their lives.

Earlier in this century, skepticism about this account was widespread within the LDS community, particularly among the more educated. It should also be noted that understanding of the book itself was not then far advanced: almost no serious studies of the book and its contents had been published, and the book was not heavily used in worship service discourse or in gospel instruction. The Latter-day Saints were not prepared for the skepticism of scripture that had swept through liberal Protestantism and that dominated the Christian schools of theology where LDS religious educators were studying for advanced degrees.

Scholarly interest in the Book of Mormon developed in the early part of the century among amateur and professional archaeologists. By midcentury, Sidney B. Sperry, Hugh W. Nibley, John L. Sorenson, and a few others had launched serious scholarly inquiries into the book itself. All of these began with the faithful assumption of the book’s divine origins. In the mid-1970s the rate of publication on Book of Mormon topics began to soar. The Church worked the Book of Mormon into the regular cycle of the new correlated curriculum for adults, and Church leaders began using the Book of Mormon more frequently and systematically in speeches and instructional situations. As Latter-day Saints have more regularly and systematically engaged themselves in the Book of Mormon in both personal and scholarly study, its authenticity as an ancient scriptural record has become more firmly and generally established. Vocal doubters are a small and shrinking minority that finds itself much closer to anti-Mormons in its interests and views than to the general LDS community.

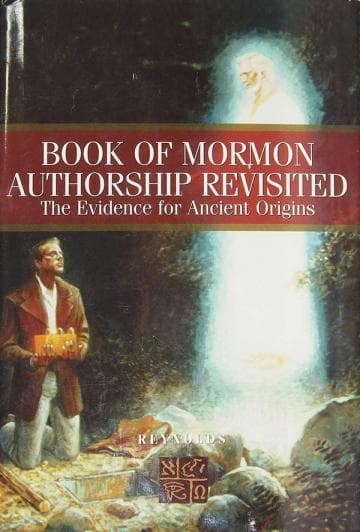

The growth of scholarly studies on the Book of Mormon continues to produce an accumulation of significant insights into the authorship of the book. In 1982 I edited a volume of these studies for BYU’s Religious Studies Center. The Center gave the imprint to FARMS for the 1996 reprint edition. The present volume addresses some issues treated in the 1982 volume and several others that have surfaced in the last fifteen years to provide a broad look at the authorship question as it stands at the end of the century. Updating and extending this discussion seems appropriate given the large amount of new evidence of the ancient origin of the Book of Mormon that has accumulated from scholarly studies and the renewed efforts of the book’s detractors to refute the LDS account.

While most of the scholarly work Latter-day Saints have done on the Book of Mormon is directed primarily at improving our understanding of its contents, it inevitably has implications for the authorship question. Because of the endless chorus of criticism from dissident Mormons and anti-Mormons , it may be useful to sum things up periodically and to provide the LDS community with an organized presentation of the state of knowledge on this subject. This book is intended to provide that kind of resource for those interested in following these issues and for those who may desire to help someone who is troubled by the anti-Mormon arguments against the divine origin of the Book of Mormon.

The contributors to this volume are not trying to “prove” the authenticity of the Book of Mormon. We understand from personal experience that knowledge of the truthfulness of the Book of Mormon is a spiritual and personal matter. Our primary objective is to understand the book itself and to share whatever understanding we might gain. But we also recognize that it may be important for young people or others who wonder about these things to know that the most serious scholarly students of the Book of Mormon are led to conclusions exactly opposite those of the book’s critics. Faithful scholars have turned up evidence that refutes most of the criticisms, and they have found mountains of evidence for the book’s ancient origins—evidence that is rarely confronted squarely by critics. Many of us expressed our personal views on these questions in the 1996 FARMS/Deseret Book publication, Expressions of Faith: Testimonies of Latter-day Saint Scholars, and in the current volume we share the results of a number of scholarly inquiries conducted by us and others. We are all dependent on the works of others in order to build our knowledge.

This volume is divided into four sections. Part 1 deals with various accounts of how the Book of Mormon was actually produced in 1829 and 1830, emphasizing the translation process and the witnesses who saw the plates. In part 2 we look at the structure of the authorship debate and its arguments and review the history of alternative theories and criticisms of the Book of Mormon. Part 3 presents textual studies that demonstrate the plausibility of the Book of Mormon as an ancient book, and part 4 updates the attempts to understand the ancient geographical and cultural setting of the Book of Mormon in both the Old and New Worlds.

In chapter 2, Richard L. Bushman recounts the events leading up to the March 1830 publication of the Book of Mormon with an illuminating commentary on the contrasting tendencies of LDS and secular scholars to emphasize or de-emphasize different parts of the historical record. This fresh look at a much analyzed history transports us back in time and presents these events from the perspective of the participants. Joseph’s 1832 account is quoted in full, helping us to appreciate more than ever his ongoing effort to understand his own divine mission. The involvement of other key players is also illuminated with contemporary personal perspectives. The sixty-three-day time of translation that produced the final book, together with the matter-of-fact moving on to other things at its completion, help us understand both why this divinely revealed scripture was so crucial as an evidence of God’s role in this restoration and why the church organized by Joseph Smith did not intensively study its contents for another hundred and twenty years. Though Bushman refers only briefly to anti-Mormon and secular interpretations of the events surrounding the coming forth of the Book of Mormon, his approach makes clear how difficult it is to match any alternative account to the historical evidence. As students of the Book of Mormon learn about the successive complexities and ancient elements in the book, they are forcibly reminded that the manuscript was translated by Joseph with his scribes, grinding out seven to nine pages a day, never reviewing even the previous sentence or page, and using no notes. This process is well documented, but it is difficult to imagine even the most educated genius writing such a complex book in this manner. Those who have written complex histories or other kinds of books know that this task is impossible, though others might be tempted to believe that such writing is relatively easy. The most plausible explanation, unless one disallows all reference to the divine, is the one given by Joseph and the other witnesses. Joseph did not write the book; rather, he read it as it was given to him through interpretive instruments, such as the seer stone, much like we today would read material off a computer screen. The writing was the combined effort of dozens of ancient authors who lived over a thousand-year period.

Richard L. Anderson’s ongoing studies on the Book of Mormon witnesses are well-known and have posed some of the most serious obstacles to secular and anti-Mormon interpretations of the Book of Mormon and its origin. Eleven men were formally shown the plates. They hefted and handled the ancient writings and satisfied themselves of their real existence in every way. Others had less formal exposure to the plates, but they, too, left their testimonies. As Anderson has demonstrated,1 these witnesses all consistently maintained that their original account was true throughout their lives. Their commitment to those original accounts was tested severely when several of them fell into circumstances that would have rewarded them richly to expose Joseph Smith had they any sense of having been duped by some fraud, but none did that, for they all knew there was no fraud to expose. Because these accounts are so strong, critics and skeptics often ignore them altogether. In chapter 3, Anderson sets forth the personal writings of Joseph Smith and six of the eleven witnesses that explain their experiences with the gold plates.

Royal Skousen’s exhaustive analysis of the manuscripts that were produced in the translation process shows that new light can be shed on these events when they are viewed from new scholarly perspectives. Skousen has carefully analyzed all the manuscript variations, corrections, and physical features, and he finds the eyewitness accounts of the translation process to be wholly credible. Joseph dictated without reference to any notes, papers, or even the plates themselves; he relied wholly upon the Urim and Thummim and the seer stone. Joseph spelled out the strange new Book of Mormon names and other unfamiliar words, and scribes read back to him their transcription to allow him to check for accuracy. New sessions began without any review of the last transcribed material. Skousen’s analysis of the translation process leads him to conclude that the witnesses’ view that some level of control was exerted over Joseph’s selection of words is supported by the manuscript evidence. The people closest to the translation process had no doubts that it was divinely directed; in fact, they could not imagine that Joseph was capable of writing such a book on his own. The evidence in the manuscript supports them consistently.

Louis C. Midgley leads out in the analysis of the authorship debate in part 2 with a concise history of the alternative theories advanced by those who reject Joseph Smith’s account of Book of Mormon origins. The Book of Mormon presents a different problem for Joseph’s detractors than does his first vision. Visions have no secondary witnesses, nor do they leave historical evidence, but the 1830 Book of Mormon contained 590 pages of text, which is the most important kind of evidence historians can find. The existence of the book must be explained—even explained away—if Joseph’s prophetic powers are to be discounted. Thus the critics have given a variety of alternative explanations, ably surveyed by Midgley. The first critics agreed that Joseph was not the kind of man who could have written such a book, so they looked for someone who could. Sidney Rigdon and Solomon Spaulding were early candidates, but neither can be plausibly defended as the book’s author. Later critics proposed epilepsy and other psychological abnormalities to explain Joseph’s seemingly miraculous achievement, but they failed to acknowledge that there is no evidence for such abnormalities in Joseph’s life and that historically no such abnormalities have ever contributed to the writing of such a complex book. Others assumed that Joseph was a conscious fraud, but even this fails to reconcile this highly complex work with the ignorance and inexperience of the supposed author. In 1945, Fawn M. Brodie attempted a gentler explanation, arguing that although Joseph’s religious career began fraudulently, he gradually came to believe his own lies, but this solved no problems, and Hugh Nibley and others have since exposed the weaknesses in her logic and evidence. More recently, Mormon historians who have trouble accepting Joseph’s account have argued for some kind of middle ground that would accept the religious value of the Book of Mormon but attribute its origins to nineteenth-century frontier culture. Midgley chronicles, evaluates, and criticizes all these approaches, documenting their meanderings, contradictions, and other shortcomings. He notes the cycles in these explanations and their failure to make any real progress, especially when compared with the booming scholarship based on the assumption that Joseph’s account is true. Readers who have heard of these various alternative theories but have been unable to sort out their mutual connections will find this chapter especially valuable.

Daniel C. Peterson is a seasoned defender of the Book of Mormon against its critics. He currently helps oversee the FARMS criticisms project of collecting, documenting, and responding to all published criticisms according to the present state of Book of Mormon scholarship. In chapter 6, Peterson summarizes that situation and sets forth the current argument on some of the best-known and most typical criticisms. He surveys critics’ allegations about textual changes, anachronisms, historical and archaeological implausibilities, inconsistencies with Mormon doctrinal beliefs and attempts to identify alternative authors. Peterson shows convincingly that the best scholarship available does not support these criticisms, and that, in fact, it converts most of them into powerful evidence for the authenticity of the Book of Mormon as an ancient text with Middle Eastern origins.

Hugh Nibley developed and perfected the argument of the complexity of the Book of Mormon as both an answer to many criticisms of the Book of Mormon and as a basis for evidence that the book is an authentic ancient text. Throughout his writings on this subject, Nibley identifies subtle and complex interrelationships between linguistic, historical, cultural, and textual features of the Book of Mormon that can only be appreciated in light of scholarship that has been published since 1830. This argument points to Joseph Smith’s lack of education and the book’s being dictated line by line without notes and without reviewing what was said minutes, hours, days, or even months earlier. Yet despite these circumstances, a large number of complex relationships are developed in the book and are maintained consistently from beginning to end. Many of these relationships have taken scholars longer to sort out than it took Joseph Smith to translate the entire book. The Book of Mormon has at least three independent dating systems that are maintained accurately throughout. It has a complex system of religious teachings that are enriched as new sermons are added throughout the text but are never confused or contradicted. The book’s authors refer to a huge and complex set of sources, including official records, sermons, letters, monument inscriptions, and church records, which always maintain a consistent relationship in the final text. Subtle and complex political traditions evolve early in the text and surface in a variety of forms in later sections, always plausibly and consistently. The book describes various ebbs and flows of ethnic interaction without once losing track of even the most minor groups. Hundreds of individual characters are successfully introduced and coherently tracked. The geographical data in the text is diverse and complex, yet when carefully analyzed makes perfect sense and matches an identifiable portion of Mesoamerica quite well. This list of examples could go on at great length.

In chapter 7, Melvin J. Thorne explicates Nibley’s argument from complexity, reviewing a number of important examples, including some that are presented in this volume. Thorne goes on to point out the mounting improbability of the alternative theories as the number of elements establishing Book of Mormon complexities increases. He draws on the simple rule that the probability of two events occurring by chance at the same time is equal to the product of their separate probabilities of occurring at all. In other words, two events that are likely to occur half the time independently are likely to occur jointly only one quarter of the time (.5 x .5 = .25). From a probabilistic point of view, the large number of ancient elements that exist in the Book of Mormon , which would be natural in an ancient book but not in a nineteenth-century production, yields a joint probability that is astronomical against its being a nineteenth-century composition that just by chance is historically and culturally accurate.

The textual studies in part 3 begin with a review of chiasmus in the Book of Mormon, one of the most intrinsically interesting and convincing of the book’s ancient features . John W. Welch first discovered these chiastic features of the text as a missionary in the 1960s, and in a series of publications he has developed the study of this structural device in the Book of Mormon and other ancient literature of Middle Eastern origin. In chapter 8, Welch examines the last thirty years of study of this phenomenon, including criticisms and uncritical excesses. In summarizing the evidentiary value of chiasmus today, he finds it stands stronger than ever as clear evidence of a tradition of writers that understood and valued this particular literary structure for its aesthetics and its power to communicate at multiple levels simultaneously. No better explanation exists for the prevalence of high-quality chiasms in the Book of Mormon than its ancient biblical roots.

The 1982 authorship volume included a wordprinting study of Wayne Larsen and Alvin Rencher that used statistical analyses of relative frequencies of noncontextual terms to determine that neither Joseph Smith nor his close colleagues were authors of the Book of Mormon and that over two dozen separable portions of the book were authored by different people. In the 1980s John L. Hilton and five of his associates in the Bay Area (three non-LDS) tested these results using a completely independent analysis. Borrowing the tests of the Scottish forensics specialist A. Q. Morton and beginning with a large controlled author study to establish statistical significance, Hilton’s group eventually confirmed the view that different authors can be distinguished within the Book of Mormon, and that none is Joseph Smith or any of the other nineteenth-century candidates that have been proposed. In some methodological respects, the new study was critical of the first, but the original findings were confirmed, planting another enormous obstacle in the road of anyone wishing to assert that the Book of Mormon was authored in the nineteenth century. Hilton’s statistical techniques were critically reviewed and accepted by the University of Chicago Press prior to its publication of a recent book that, using these same statistical techniques, identified previously unrecognized writings of the seventeenth-century English philosopher Thomas Hobbes.2 Hilton’s 1990 paper reporting his Book of Mormon findings is reprinted in chapter 9 with minor modification.

Most thoughtful readers of the Book of Mormon have probably wondered at the large numbers of people that the text describes as having descended from the two or three dozen original settlers in the Lehite colony. Anti-Mormon critics of the book have seized on this intuitively obvious “flaw” as evidence for the book’s fraudulence. In chapter 10, James E. Smith, one of the chief architects of the Cambridge model for estimating historical populations , which is used widely by professional demographers, points out that population studies fail badly when they rely on intuition or common sense. Trustworthy historical records support a much less intuitive model of population growth and decline. Applying the Cambridge model to the Book of Mormon accounts, Smith finds the numbers reported in the text to be on the high end of what would be predicted scientifically but still plausible. Relaxing any of his perhaps unduly conservative assumptions would move Book of Mormon numbers closer to the middle of the expected range. Most important, if the Nephites or Lamanites absorbed any other unmentioned populations, the numbers cease to be at all problematic.

Several years ago, Donald W. Parry produced The Book of Mormon Text Reformatted according to Parallelistic Patterns, showing Book of Mormon readers how extensively parallelisms are used in that text. Parry has identified examples in the Book of Mormon of most biblical forms of parallelism. In chapter 11, he presents and examines three specific parallelistic patterns in their Book of Mormon exemplifications—climactic forms, synonymous parallelisms, and alternating parallel lines. He provides helpful explanations of these poetic and rhetorical structures that are richly illustrated with clear examples from the text of the Book of Mormon. Not only does the identification of these structures enrich our reading of the Book of Mormon, it also constitutes another impressive challenge to Book of Mormon critics: in addition to explaining how Joseph Smith could have written the book, they now must explain how he could have ignorantly introduced such beautiful examples of Hebrew poetic structures.

In chapter 12, John A. Tvedtnes advances an original analysis of a beautiful Book of Mormon complexity that has eluded earlier readers. Using Paul’s conversion story as related variously in several texts, Tvedtnes focuses on Alma’s account of his somewhat similar conversion experience and its retellings in different Book of Mormon contexts. Through careful analysis of each of these passages, Tvedtnes shows the rich emotional content of Alma’s memory as well as the doctrinal implications Alma draws from the experience and how they occurred to him and developed in each retelling. Tvedtnes builds on this analysis to show that Mormon actually quotes each of these passages from the original record rather than reporting them third person. Finally, Tvedtnes details how each retelling is unique and supplements the others with additional information. Taken as a whole, the retellings are consistent, different in detail, and highly reinforcing. Given the translation process, this is again a seemingly impossible achievement if Joseph, or anyone besides Alma himself, was making up these widely scattered passages.

In chapter 13, John W. Welch compares the Book of Mormon with another ancient text, in this case the Narrative of Zosimus, which circulated in early Christian circles and appears to have Hebrew origins but was certainly unknown to Joseph Smith and his contemporaries. Zosimus records a dream remarkably similar to Lehi’s tree of life vision and a revelation about a group much like Lehi’s colony that was led out of Jerusalem to an ideal land. Welch presents the Zosimus text, translated from both Greek and Syriac versions, together with verses from the Book of Mormon that contain parallel information. While Welch readily acknowledges the impossibility of determining the connections between these two amazingly similar accounts, the unquestionable antiquity of the Zosimus text would seem to confirm the antiquity of the Book of Mormon and to indicate that the two texts may share some common origins.

The final section of this volume addresses the geographical and archaeological speculations that have fascinated Book of Mormon believers from the earliest years. If the book is a true ancient record, the Nephites lived somewhere in real time in a real historical and cultural context. The history of Book of Mormon studies has always featured vigorous efforts to identify the geographical and cultural context of Nephite times (600 b.c.— a.d. 421). Two distinct geographical contexts are featured in the Book of Mormon: the journey from Jerusalem across the Arabian peninsula and the promised land itself where Lehi’s descendants dwelled for a thousand years. The Jaredite record tells little about their journey and provides no directions, but their history occurred in an area that overlapped Nephite territory. The last two chapters of this volume articulate what is known about this subject at the present time, which is much more than is commonly realized.

In chapter 14, Noel B. Reynolds draws extensively on Warren P. and Michaela Knoth Aston’s research on Lehi’s exodus from Jerusalem .3 Relying on their earlier work and his own subsequent research and field work with them, Reynolds summarizes what can be said about this journey through the Arabian peninsula and the building of the ship at Bountiful. The text provides remarkably helpful directions and descriptions that have helped make it possible to identify plausible sites for Nahom, where Ishmael was buried, and Bountiful, where the ship was built. As Eugene England pointed out in the 1982 authorship volume, at the time the Book of Mormon was written, no Americans or Europeans believed that fertile coastal locations of the kind the Book of Mormon describes existed in Arabia, yet at least one site has now been identified west of Salalah in Oman that appears to meet every one of the specific features described in the text. In 1830, including such a description in a fraudulent account presenting itself as truthful would have been foolhardy. The ancient authorship and accuracy of the Book of Mormon are strongly reinforced by these findings.

Most of the geographical speculation on the Book of Mormon has focused on the effort to identify Book of Mormon lands in the New World, which would also pinpoint a cultural group at that point in history. Mesoamerica has been the focus of almost all of that research in recent years. Where else does a narrow neck of land exist between two seas and a literate civilization build cities for hundreds of years b.c.? John L. Sorenson has done more than any other person to identify the geographical issues in the Book of Mormon and to explore the possible areas where these peoples could have lived. In chapter 15, Sorenson updates his detailed comparison of the Book of Mormon itself and the lineage histories written by Mesoamerican peoples in the post-Nephite period. The extensive parallels between these different writings indicate strongly that the Book of Mormon fits nicely into the cultural context of ancient Mesoamerican books. Because Joseph Smith knew nothing about ancient Mesoamerican books, it is hard to see how he could have come up with such a match. Like his associates in the early Church, Joseph assumed that the Book of Mormon peoples had probably covered the entire Western Hemisphere and that all Indians were Lamanite descendants. Only in the last few decades has it become clear that the Book of Mormon narrative describes Nephite and Lamanite homelands that were confined to a few hundred miles in diameter during the entire thousand-year history. These and numerous other textual details escaped both translators and readers of the Book of Mormon for a hundred years. The book describes a cultural context not unlike that in ancient Mesoamerica but which is quite different from what Joseph and his contemporaries understood or expected. This clearly undercuts any theory that would attribute authorship of the Book of Mormon to Joseph or his associates.

The concluding chapter is a reprint of William J. Hamblin’s summary of the important work scholars have done on warfare in the Book of Mormon. Hamblin shows that in dozens of dimensions, the assumptions and complex details of Book of Mormon warfare are consistent with ancient as opposed to modern warfare, specifically ancient Mesoamerican warfare.

The studies in this volume are offered to students of the scriptures in the hope that they will help them think about the authorship issues raised by critics of the Book of Mormon. While we can never scientifically prove that the Book of Mormon was written by Nephite prophets, we can show through scientific and other scholarly studies where the criticisms of the book fail. Science and logic can prove negative, but not positive, claims. Students who desire a fully satisfying resolution of these questions will do best to accept Moroni’s invitation to find their own spiritual witness of the book’s truth through personal study and prayer.

We gratefully acknowledge the permission of BYU Studies to reprint John Hilton’s wordprint study and a revised version of John W. Welch’s Zosimus paper. We also acknowledge the Review of Books on the Book of Mormon for permission to use a revised version of James Smith’s earlier treatment of the population issue in its pages. FARMS and Deseret Book have allowed us to reprint William Hamblin’s conclusions from Warfare in the Book of Mormon.

Theresa S. Brown and Thomas J. Lowery have been helpful in preparing these materials for publication. Davis Bitton generously provided thoughtful criticisms and suggested revisions for the entire text, and a special thanks is owed to Jessica Taylor, Mary Mahan, and Melvin J. Thorne of the FARMS editorial staff for their gentle but expert guidance in producing the final version of this manuscript. Above all, I acknowledge the constant encouragement and support of my wife Sydney. If this work meets her approval, I am happy enough.

1. Richard L. Anderson, Investigating the Book of Mormon Witnesses (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1981).

2. See Thomas Hobbes, Three Discourses: A Critical Modern Edition of Newly Identified Work of the Young Hobbes, edited with explanatory essays by Noel B. Reynolds and Arlene W. Saxonhouse (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995).

3. See Warren P. Aston, In the Footsteps of Lehi: New Evidence for Lehi’s Journey across Arabia to Bountiful (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1994)

Book

20 Chapters

Items in the BMC Archive are made publicly available for non-commercial, private use. Inclusion within the BMC Archive does not imply endorsement. Items do not represent the official views of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints or of Book of Mormon Central.