KnoWhy #627 | February 17, 2023

Why Were Man and Woman Created in the Image of God?

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

“Seest thou that ye are created after mine own image? Yea, even all men were created in the beginning after mine own image.” Ether 3:15

The Know

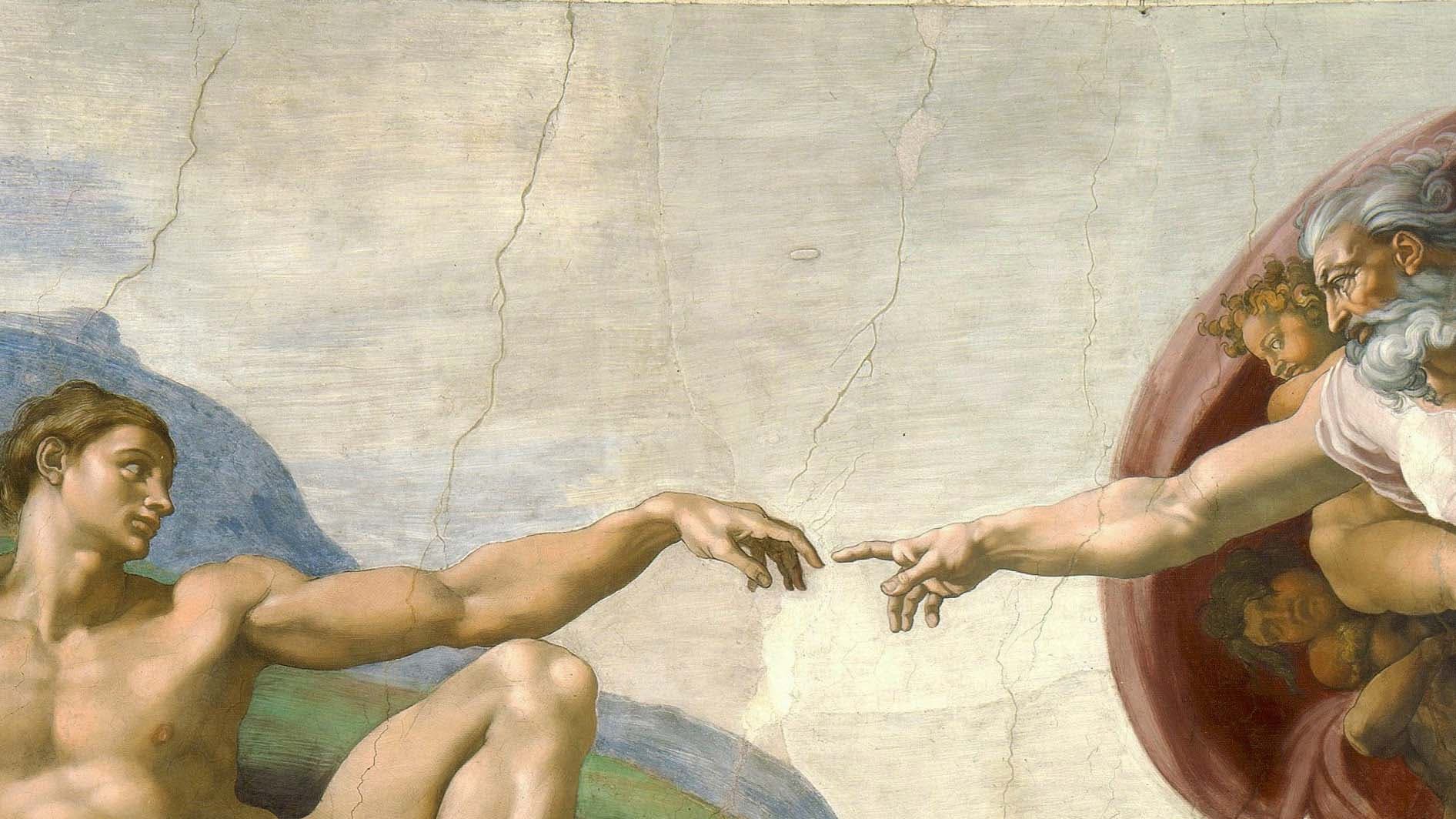

In the cosmic Creation account in Genesis 1, the culmination of God’s Creation is man and woman, who are created in God’s “image” (selem) and “likeness” (demut) (Genesis 1:26–27).1 For centuries, the Judeo-Christian tradition has wrestled with the theological implications of this statement since mainstream theology in both Jewish and Christian traditions portrays God as without body, parts, or passions—an unresponsive being, who cannot be influenced or acted upon.

For instance, one Jewish scholar reasoned that being in “the image of God” only entails a variety of abstract (non-physical) qualities: “all those faculties and gifts of character that distinguish man from the beast,” such as “intellect, free will, self-awareness, consciousness of the existence of others, conscience, responsibility, and self-control.”2 Similarly, a Christian scholar concluded that “it implies that it is those human characteristics that enable him to fulfill his duty of ruling the earth.”3 Neither scholar mentions or implies physical, bodily form as being part of God’s image.

Without denying that there are other factors at play, Restoration scripture makes clear that humanity’s status as the image of God includes a physical resemblance to deity. In Ether 3, the brother of Jared “saw the finger of the Lord; and it was as the finger of a man, like unto flesh and blood” (Ether 3:6). Because of his great faith, “the Lord showed himself unto him” (v. 13) and said:

Behold, I am Jesus Christ. … Seest thou that ye are created after mine own image? Yea, even all men were created in the beginning after mine own image. Behold, this body, which ye now behold, is the body of my spirit; and man have I created after the body of my spirit; and even as I appear unto thee to be in the spirit will I appear unto my people in the flesh. (Ether 3:14–16)

Here, the premortal Christ reveals that humanity was created in the image of His spirit body, which has the same form and appearance as His future body of flesh. Similarly, Joseph Smith’s inspired revision of Genesis 1:26–27, now canonized as part of the book of Moses, indicates that humankind is in the image of the premortal Christ, who in turn is Himself in the image of the Father:

And I, God, said unto mine Only Begotten, which was with me from the beginning: Let us make man in our image, after our likeness; and it was so. … And I, God, created man in mine own image, in the image of mine Only Begotten created I him; male and female created I them. (Moses 2:26–27)

Genesis 5:1–3 echoes Genesis 1:26–27, stating “that God created man, in the likeness of God made he him; male and female created he them,” and then adding that Adam had “a son in his own likeness, after his image; and called his name Seth.” In the book of Moses, this is revised to explicitly refer to the bodily image of God:

In the day that God created man, in the likeness of God made he him; In the image of his own body, male and female, created he them. … And Adam lived one hundred and thirty years, and begat a son in his own likeness, after his own image, and called his name Seth. (Moses 6:8–10).

The Book of Mormon and the book of Moses were translated in 1829 and 1830, respectively.4 Thus, humanity’s physical resemblance to deity was one of the earliest truths restored in modern times—a truth which Joseph Smith himself surely understood even earlier thanks to his First Vision.5

These passages from Restoration scripture accurately reflect the understanding of God’s “image” and “likeness” from an ancient Near Eastern perspective.6 In recent years, biblical scholars have increasingly recognized that the human-like presentation of God in the Hebrew Bible is not intended to be read metaphorically.7 Specifically, several scholars have noted that man being in God’s “image” (selem) and “likeness” (demut) in Genesis 1:26–27 and 5:1–3 has a physical dimension to it—precisely as indicated in Restoration scripture.

For example, the eminent biblical scholar David Noel Freedman explained:

[W]e note that humanity occupies a unique status in contrast with all the other created beings on the earth: being made in the image and according to the likeness of God. The basic likeness is in physical appearance, as the study of the etymology and usage of both terms shows. … These terms are used in cognate languages of statues representing gods and humans in contemporary inscriptions, and certainly the intention is to say that God and man share a common physical appearance.8

Similarly, after quoting Genesis 1:27, Charles Halton states, “It seems pretty straightforward that if God created humans in the divine image then God must look like a human.”9 Benjamin Sommer likewise states, “The terms used in Genesis 1:26–27, demut and selem, … pertain specifically to the physical contours of God. This becomes especially clear when one views the terms in their ancient Semitic context. They are used to refer to visible, concrete representations of physical objects … [and] there is no evidence suggesting we should read these terms as somehow metaphorical and abstract.”10

Both ancient Jews and early Christians recognized the biblical description of God’s “image” as being like that of man, and they took such descriptions literally.11 Theologian David L. Paulsen has shown that it was only after Christianity and Judaism became influenced by Greek philosophical metaphysics that such interpretations changed.12

The Why

Joseph Smith taught that “it is necessary for us to have an understanding of God himself in the beginning,” and stressed that in order to obtain a correct understanding of God, we must start from a sound foundation. “If we start right, it is easy to go right all the time, but if we start wrong, it is a hard matter to get right.”13 Having a proper understanding of God’s embodiment—and the meaning of humanity being in God’s “image” and “likeness”—is foundational to gaining a proper relationship between God and man.

The clear implication of humanity—both male and female—being created in God’s image is that all men and women are the offspring of God. Halton argues, citing Genesis 5:1–3, “We look like the divine because we are God’s offspring.”14 Prophets and apostles and other servants of the Lord have repeatedly taught the importance of this solemn truth. For instance, President Hugh B. Brown taught:

For us, God is not an abstraction. He is not an idea, a metaphysical principle, an impersonal force or power. He is a concrete, living person. And though in our human frailty we cannot know the total mystery of his being, we know that he is akin to us, … and he is, in fact, our Father. … We reaffirm the doctrine of the ancient scripture and of all the prophets that asserts that man was created in the image of God and that God possessed such human qualities as consciousness, will, love, mercy, justice. In other words, he is an exalted, perfected, and glorified Being.15

This proper understanding of God makes each individual’s relationship with God intimate and personal. It also promotes an ennobling view of men and women everywhere. In the ancient Near Eastern context, the “image of God” (or the gods) was commonly thought to be invested in royalty, but Genesis extends this royal concept to all of humanity.16

Furthermore, God commanded the Israelites not to make any graven images of God to bow down and worship (see Exodus 20:3–4; Deuteronomy 4:15–19), at least partially because rather than “dumb idols” (Habakkuk 2:8), God’s true image is manifest in living, breathing persons.17 This means, every human being deserves to be treated with dignity and respect as children of God and reflections of his image and likeness. As President Joseph Fielding Smith taught,

The God we worship is a glorified Being in whom all power and perfection dwell, and he has created man in his own image and likeness (Gen. 1:26–27), with those characteristics and attributes which he himself possesses. And so our belief in the dignity and destiny of [humankind] is an essential part both of our theology and of our way of life. It is the very basis of our Lord's teaching that “the first and great commandment” is: “Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind”; and that the second great commandment is: “Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself” (Matt. 22:37–39).18

Aaron P. Schade and Matthew L. Bowen, The Book of Moses: From the Ancient of Days to the Latter Days (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2021), 131–143.

Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 6:191–194.

David L. Paulsen, “The Doctrine of Divine Embodiment: Restoration, Judeo-Christian, and Philosophical Perspectives,” BYU Studies Quarterly 35, no. 4 (1995–1996): 7–94.

Edmond LaB. Cherbonnier, “In Defense of Anthropomorphism,” in Reflections on Mormonism: Judaeo-Christian Parallels, ed. Truman G. Madsen (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1978), 155–171.

- 1. On humanity as the culmination of God’s creation, see Gordon J. Wenham, “Genesis,” in Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible, ed. James D. G. Dunn and John W. Rogerson (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2003), 38–39.

- 2. Nahum M. Sarna, Understanding Genesis: Through Rabbinic Tradition and Modern Scholarship (New York, NY: Jewish Theological Seminary of America, 1966), 15–16.

- 3. Wenham, “Genesis,” 39.

- 4. John W. Welch, “The Miraculous Timing of the Translation of the Book of Mormon,” in Opening the Heavens: Accounts of Divine Manifestations, 1820–1844, 2nd ed., ed. John W. Welch (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: BYU Press, 2017), 123, dates the translation of Ether 3 to May 25, 1829. Patrick A. Bishop, Day After Day: The Translation of the Book of Mormon, 2nd ed. (Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2018), 101, dates it a few days earlier to May 21, 1829. On the dating of the book of Moses translation, see Kent P. Jackson, The Book of Moses and the Joseph Smith Translation (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2005), 3.

- 5. For a more complete discussion of the embodiment of God in the earliest stages of the Restoration, see David L. Paulsen, “The Doctrine of Divine Embodiment: Restoration, Judeo-Christian, and Philosophical Perspectives,” BYU Studies Quarterly 35, no. 4 (1995–1996): 9–39. See also Terryl L. Givens, Wrestling the Angel: The Foundations of Mormon Thought—Cosmos, God, Humanity (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2015), 89–95. On what Joseph would have known about God’s body after the First Vision, see John W. Welch, “When Did Joseph Smith Know that the Father and the Son Have Bodies as Tangible as Man’s?,” BYU Studies Quarterly 59 no. 2 (2020): 298–310.

- 6. See Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 6:191–194; Aaron P. Schade and Matthew L. Bowen, The Book of Moses: From the Ancient of Days to the Latter Days (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2021), 134–137.

- 7. For two very recent treatments of the subject, see Charles Halton, A Human-Shaped God: Theology of an Embodied God (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox, 2021); Francesca Stavrakopoulou, God: An Anatomy (New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 2022). See also Esther J. Hamori, “When Gods Were Men”: The Embodied God in Biblical and Near Eastern Literature (New York, NY: Walter de Gruyter, 2008); Benjamin D. Sommer, The Bodies of God in the World of Ancient Israel (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2009); Mark S. Smith, Where the Gods Are: Spatial Dimensions of the Anthropomorphism in the Biblical World (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016); Andreas Wagner, God’s Body: The Anthropomorphic God in the Old Testament (New York: T&T Clark, 2019). For an earlier treatment of this topic, which is more philosophical/theological rather than historical-critical, see E. LaB. Cherbonnier, “The Logic of Biblical Anthropomorphism,” Harvard Theological Review 55, no. 3 (1962): 187–206. Chebonnier later discussed the biblical view of an anthropomorphic (human-like) God in light of Latter-day Saint teachings on this subject. See Edmond LaB. Cherbonnier, “In Defense of Anthropomorphism,” in Reflections on Mormonism: Judaeo-Christian Parallels, ed. Truman G. Madsen (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1978), 155–171.

- 8. David Noel Freedman, “The Status and Role of Humanity in the Cosmos According to the Hebrew Bible,” in On Human Nature: The Jerusalem Center Symposium, ed. Truman G. Madsen, David Noel Freedman, and Pam Fox Kuhlken (Ann Arbor, MI: Pryor Pettengill Publishers, 2004), 16–17, as cited in Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, In God’s Image and Likeness 1: Creation, Fall, and the Story of Adam and Eve, updated ed. (Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2014), 123, cf. pp. 130–131 n.2-28.

- 9. Halton, Human-Shaped God, 78.

- 10. Sommer, Bodies of God, 69–70.

- 11. See Alon Goshen Gottstein, “The Body as Image of God in Rabbinic Literature,” Harvard Theological Review 87, no. 2 (1994): 171–195; David L. Paulsen, “Early Christian Belief in a Corporeal Deity: Origen and Augustine as Reluctant Witnesses,” Harvard Theological Review 83, no. 2 (1990): 105–116; Carl W. Griffin and David L. Paulsen, “Augustine and the Corporeality of God,” Harvard Theological Review 95, no. 1 (2002): 97–118.

- 12. Paulsen, “Doctrine of Divine Embodiment,” 41–79, which is a significant expansion of Paulsen, “Early Christian Belief in a Corporeal Deity.” Paulsen also critiques the philosophical arguments against an embodied God in Paulsen, “Doctrine of Divine Embodiment,” 81–94, an adaptation of David Paulsen, “Must God Be Incorporeal?,” Faith and Philosophy 6, no. 1 (1989): 76–87.

- 13. Joseph Smith, Discourse, 7 April 1844, as reported in the Times and Seasons, August 15, 1844, 5:613, online at josephsmithpapers.org. This stands in contrast to Halton, Human-Shaped God, 18–22, in which Halton, despite correctly arguing that God is embodied, nonetheless asserts that “an accurate understanding of God is not of utmost importance” (p. 18).

- 14. Halton, Human-Shaped God, 80.

- 15. Hugh B. Brown, “The Gospel Is for All Men,” April 1969 general conference, online at scripture.byu.edu.

- 16. See Wenham, “Genesis,” 39.

- 17. See Sommer, Bodies of God, 70. Cathrine L. McDowell, The Image of God in the Garden of Eden: The Creation of Humankind in Genesis 2:5–3:24 in Light of the mīs pî pīt pî and wpt-r Rituals of Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2015), argues that Genesis 1–3 presents the creation of humanity in a way that imitates the rituals surrounding the creation of idols in Mesopotamia and Egypt, thus implying that human beings stand in the place of statutes as the true image of God. See also Catherine McDowell, “Human Identity and Purpose Redefined: Gen 1:26–28 and 2:5–25 in Context,” Advances in Ancient Biblical and Near Eastern Research 1, no. 3 (2021): 29–44. Cf. Sommer, Bodies of God, 19–24.

- 18. Joseph Fielding Smith, “Our Concern for All Our Father’s Children,” April 1970 general conference, online at scripture.byu.edu.