KnoWhy #137 | November 29, 2019

Why Was Alma’s Wish Sinful?

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

“But behold I am a man, and do sin in my wish” Alma 29:3

The Know

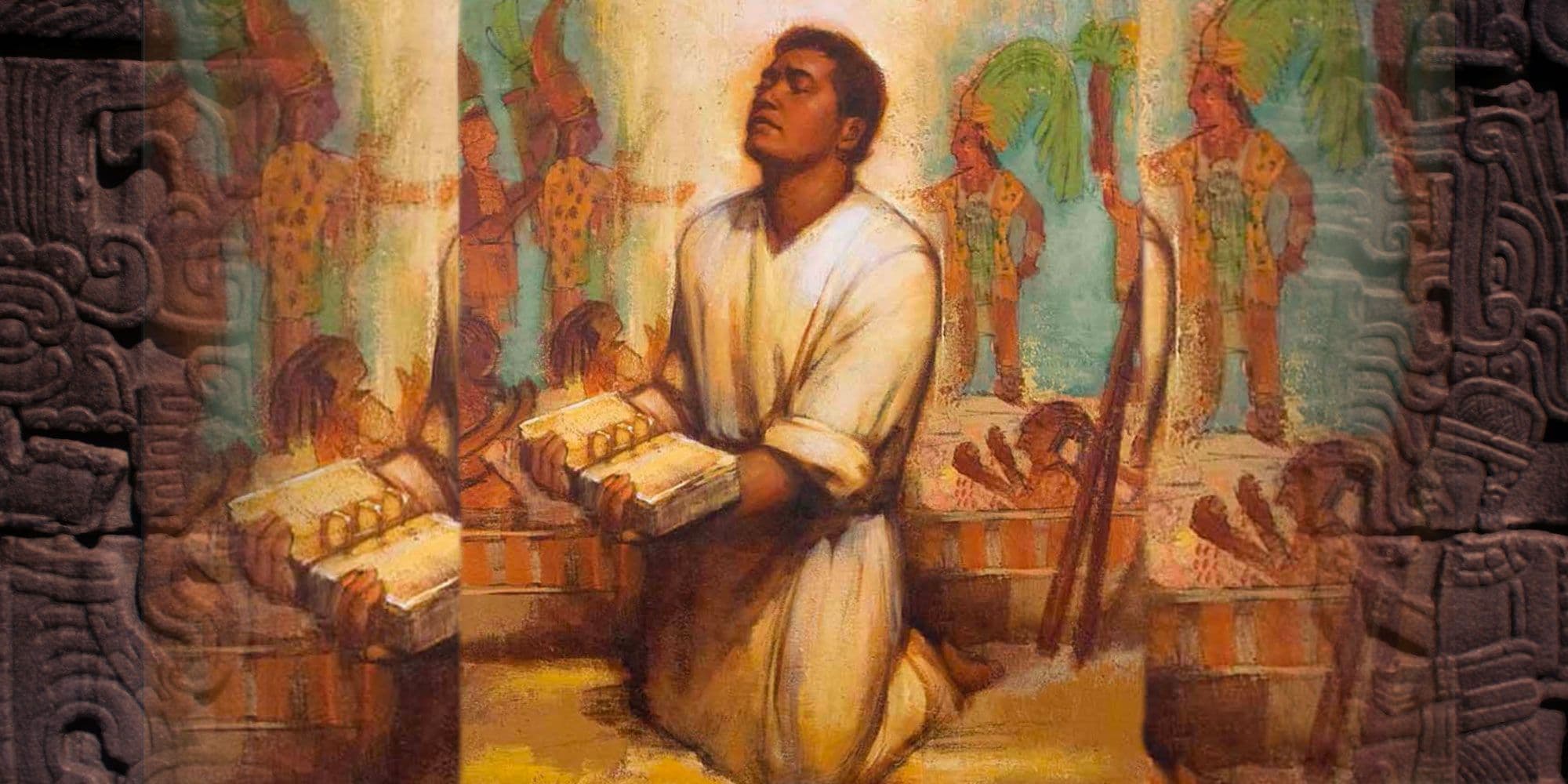

Alma 29 famously begins, “Oh that I were an angel, and could have the wish of mine heart, that I might go forth and speak with the trump of God, with a voice to shake the earth, and cry repentance unto every people!” (v. 1). To this solemn wish Alma added, “Yea, I would declare unto every soul, as with the voice of thunder, repentance and the plan of redemption, that they should repent and come unto our God” (v. 2).

At this point in his yearning, Alma confesses that he sins in his wish (Alma 29:3). To understand why, Alma 29 needs to be read from many perspectives: personally, politically, officially, poetically, and spiritually. This brief chapter is one of the most beautiful of all spiritual expressions in the Book of Mormon, standing rightfully among the best of religious literatures anywhere.

Personally, in Alma 29:1, Alma was most likely thinking of the angel of his own conversion, the one who appeared to him and called him to repentance, whose “voice was as thunder, which shook the earth” (Mosiah 27:18; see also Alma 36:7; 38:7).1 If only he could be like that angel, Alma was imagining, everyone would repent, embrace the plan of redemption, and come to the true God, and then there would be “no more sorrow upon all the face of the earth” (Alma 29:2). Painfully, Alma was indeed fully aware of many unspeakable sorrows that had recently fallen upon his people and had previously led to the deaths of many faithful Ammonites (Alma 28:3–12).

Politically, moreover, having recently learned of the great success of his friends, the sons of Mosiah, Alma may well have wondered politically whether he had succeeded or failed in his own endeavors during those 14 years when his friends had been away. During that time, Alma had seen political controversies,2 civil war,3 apostasy,4 children burned, and Ammonihah destroyed.5 In contrast to the heroic achievements of his friends, Alma had stepped down as chief judge to devote his time to reclaiming the people by “bearing down in pure testimony” (Alma 4:19), yet he could count as his main successes the conversions of a relative few, such as Amulek and Zeezrom.

Officially, as the High Priest in the city of Zarahemla, Alma certainly would have sincerely wished that he could have done more.6 Yet, in all of his high priestly glory, Alma recognizes that “this is my glory, that perhaps I may be an instrument in the hands of God to bring some soul to repentance” (Alma 29:9).7 Here, Alma realizes that he can be joyous, if only he might simply bring “some soul” to repentance. And so, all the more, Alma’s soul was “filled with joy” when he saw “many of [his] brethren truly penitent” (v. 10; cf. D&C 18:11–16).8

The Why

With Alma’s situation in mind, one can see several reasons why Alma may have sinned in his wish.

His wish usurped an angelic role that was not his. He extravagantly wished to speak even more thunderously than the angel of the Lord, by wanting to “cry repentance unto every people” and “unto every soul,” to remove all sorrow from “upon all the face of the earth” (Alma 29:1–2), effectively appropriating to himself the role and power of God.

He erred in thinking that somehow this could actually remove sorrow from all the earth. Not only would that be impossible, but it would deny the decree of God that good and evil should be placed before all men that they might choose according to their desires and thereby experience joy or remorse, as Alma himself acknowledges (Alma 29:5).

His wish reflected discontent with the things that the Lord had allotted unto him (Alma 29:3–4). His wish would have tried to re-plow the ground of God’s firm decrees,9 to counsel the Lord, and in effect to deny that “the Lord doth counsel in his wisdom, according to that which is just and true” (v. 8). On reflection, Alma recognized that his holy spiritual calling was simply to bring “some soul” to repentance.

In his wish, Alma recognized that he sinned in his heart or mind because of such desires. Elder Neal A. Maxwell taught, “desire denotes a real longing or craving. Hence righteous desires are much more than passive preferences or fleeting feelings.”10 This truth is evident here in Alma’s honest reflection. To his credit, Alma recognized that it is God’s role to grant to men “according to their desires” and “according to their wills” and that “good and evil hath come before all men” whether for “life or death, joy or remorse of conscience” (Alma 29:4–5). Alma understood the doctrine that some desires “need to be diminished and then finally dissolved.”11

Thus reaffirming to himself what he truly knew, Alma asked, “Why should I desire that I was an angel, that I could speak unto all the ends of the earth?” (Alma 29:7). To this question he immediately answered that he should not so desire, for it is in God’s wisdom that all nations shall receive, in their own tongue, as the Lord sees fit (v. 8), and because the Lord has commanded him not to “glory in [him]self,” but to “glory in that which the Lord hath commanded” (v. 9).

For years Alma had taught that “our words will condemn us, yea, all our works will condemn us; . . . and our thoughts will also condemn us” (Alma 12:14). Indeed, the law established by Alma within the church in the land of Zarahemla expressly prohibited “envyings” (Alma 1:32; 4:9; 16:18). Coveting, or envying, is a serious matter. It is connected in the Book of Mormon with strife, contention, malice, pride, swelling, and deceiving.

In order to officiate effectively as the High Priest, Alma would have needed to guard himself against any sins, including secret sins. Thoughts, wishes, and desires are potent. The culminating prohibition in the Ten Commandments is “Thou shalt not covet” (Exodus 20:17). The circumstances here, being around the beginning of a jubilee year, only added to the seriousness of anything that even approached coveting or any other transgression.12

Especially the High Priest needed to be completely pure and free from sin in order to officiate in the Holy of Holies on the Day of Atonement, the beginning of each Jubilee, on the tenth day of the seventh month (Leviticus 25:8). Finding himself discontented with the things which the Lord had allotted him would have stricken Alma to the heart. He would have recognized this as a serious sin, more so than readers today might otherwise have thought.

Indeed, his wish, if fulfilled, would have led him to disregard many things that one must spiritually remember in righteousness. It would have set Alma up ahead of his four brethren, whose great success deserved to be celebrated with the greatest of jubilation. His wish could have led Alma to glory in himself, and not to glory in what the Lord had commanded him, and could have distracted him from his responsibility to rejoice unselfishly in the successes of all other people. His wish would have diverted him away from offering his priestly prayer at the end of Alma 29, that his brethren and their converts might all “sit down in the kingdom of God” and “go no more out,” “to praise God forever.”

In Alma’s mind, missing the mark in any of these respects, let alone in all of them, would have constituted nothing less than a sin of thunderous, soul-shaking proportions. Fortunately, Alma ultimately was spiritually sensitive enough to diminish and dissolve these impulses. Alma’s glorious text ends with him thinking not of himself, but of the great success of the four sons of Mosiah who had been up to the land of Nephi, who had labored exceedingly, and had brought forth much fruit (Alma 29:17). “A sure sign of a disciple of Christ is that he or she has learned how to rejoice in the progress of others.”13

Alma concludes his poetical soliloquy, not by asking for blessings upon himself, but by offering an intercessory prayer on behalf of others. Purely he asks:

May God grant unto these, my brethren,

that they may sit down in the kingdom of God;

Yea, and also all those who are the fruit of their labor

that they may go no more out, but that they may praise him forever.

May God grant that it may be done according to my words,

even as I have spoken. Amen” (Alma 29:17).

John A. Tvedtnes, “The Voice of an Angel,” in Book of Mormon Authorship Revisited, ed. Noel B. Reynolds (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1997), 311–321.

S. Kent Brown, “Alma’s Conversion: Reminiscences in His Sermons,” in The Book of Mormon: Alma, The Testimony of the Word, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1992), 141–156, esp. 149–151.

- 1. See S. Kent Brown, “Alma’s Conversion: Reminiscences in His Sermons,” in The Book of Mormon: Alma, The Testimony of the Word, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1992), 141–156, esp. 149–151; John A. Tvedtnes, “The Voice of an Angel,” in Book of Mormon Authorship Revisited, ed. Noel B. Reynolds (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1997), 311–321. On speaking with the voice of thunder, see Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did the Angel Speak to Alma with the Voice of Thunder? (Mosiah 27:11),” KnoWhy 105 (May 23, 2016).

- 2. On the political and religious controversies caused by Nehor, see Book of Mormon Central, “Why did Nehor Suffer an ‘Ignominious’ Death? (Alma 1:15),” KnoWhy 109 (May 26, 2016).

- 3. One such conflict was with the Amlicites. See Book of Mormon Central, “How Were the Amlicites and the Amalekites Related? (Alma 2:11),” KnoWhy 109 (May 27, 2016); “Why Did Book of Mormon Prophets Discourage Nephite-Lamanite Intermarriage? (Alma 3:8),” KnoWhy 110 (May 30, 2016).

- 4. On Alma’s dealings with apostasy, see Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Alma Need to ‘Establish the Order of the Church’ in Zarahemla Again? (Alma 6:4),” KnoWhy 113 (June 2, 2016).

- 5. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why was the City of Ammonihah Destroyed and Left Desolate? (Alma 16:9–11),” KnoWhy 123 (June 16, 2016). In addition to all of this, Korihor may well have already started agitating “against all the prophecies of the holy prophets” to interrupt the “rejoicings” of the faithful (Alma 30:22). In addition, the Zoramites at that time had dissented away and had begun to build their own place of worship with the rameumptom in Antionum.

- 6. Perhaps people believed that he had great powers as the High Priest, and maybe even put pressure on him intimating that he could have—and maybe should have—done more, to call upon the powers of God to solve the many problems that had been plaguing the Nephite people.

- 7. Similarly, as the sons of Mosiah had left on their mission, they had prayed “that they might be an instrument in the hands of God to bring, if it were possible, their brethren, the Lamanites, to the knowledge of the truth” (Alma 17:9), and indeed they had become instruments in the conversion of many (Alma 26:3, 15).

- 8. At this point, Alma remembered that God has heard his prayer, that God has extended his merciful arm towards him, and that God has delivered his fathers out of captivity, and that by them God established his church (Alma 29:10–12). In the church of God, Alma had received “a holy calling, to preach the word unto this people” (v. 13), in which he had seen “much success, in the which my joy is full” (v. 13), for as the High Priest, Alma had instructed the people “to keep the commandments of the Lord; and they were strict in observing the ordinances of God, according to the Law of Moses” (Alma 30:3).

- 9. Alma conceded, “I ought not to harrow up in my desires the firm decree of a just God” (Alma 29:4). Harrowing involves breaking up the ground for planting crops. So Alma realizes that the he is seeking to “break up” the firm decree of God, a desire which is sinful.

- 10. Elder Neal A. Maxwell, “According to the Desire of [Our] Hearts,” Ensign, November 1996, 21–22.

- 11. Maxwell, “According to the Desire of [Our] Hearts,” 21–22.

- 12. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Alma Wish to Speak ‘with the Trump of God’? (Alma 29:1),” KnoWhy 136 (July 5, 2016).

- 13. Ed J. Pinegar and Richard J. Allen, Commentaries and Insights on the Book of Mormon: 1 Nephi to Alma 29 (American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, 2007), 620.