KnoWhy #729 | May 17, 2024

Why Does King Benjamin Deny Being More than a Man?

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

“I have not commanded you to come up hither that ye should fear me, or that ye should think that I of myself am more than a mortal man.” Mosiah 2:10

The Know

Some aspects of King Benjamin’s speech, given at the temple to announce Mosiah as the next king, may seem odd to modern readers.1 One such example is the explicit statement that Benjamin did not want the people to “think that I of myself am more than a mortal man” (Mosiah 2:10). This statement, along with Benjamin’s insistence that “I, even I, whom ye call your king, am no better than ye yourselves are,” can be further understood in the ancient context of the Book of Mormon, specifically regarding ideas about royalty in the Old and New Worlds (Mosiah 2:26). Indeed, as Mark Alan Wright and Brant A. Gardner have observed, “such descriptions make little sense unless the conditions he described as absent under his reign were actually common elsewhere.”2

Throughout the ancient world, the belief that kings were in some way divine was prevalent, and it was commonly believed that when kings were coronated they became gods. Israelites, and by extension the Nephites, believed that God was the true King of Israel and that earthly kings were His representatives, but the idea of a divine king as found in both the Old and New Worlds would have been a familiar concept to Book of Mormon people in either context. Indeed, it would appear that King Benjamin was all too familiar with those ideas and responded to them by pointing his people to the true divine King, Jesus Christ.

Understanding ideas about divine kingship in the ancient world can illuminate other aspects of King Benjamin’s speech. Much work situating these and other aspects of King Benjamin’s speech within an Old World context, especially within ancient Israelite festivals and coronations, is well known.3 Lesser known, however, is scholarship additionally illustrating how Benjamin’s speech would have fit into a New World context as well. Especially evident in this work is how Benjamin subverts the traditions about divine kingship that his people may have been familiar with in order to point them to Jesus Christ—the true heavenly king.

This can be seen in the immediate context of the sermon: Benjamin declaring that his “son Mosiah is a king and a ruler” over the people (Mosiah 2:30). This public declaration followed a more intimate one between the father and son the day before (see Mosiah 1:10). This same pattern of private coronations followed by public announcements can be seen in Mesoamerican cultures. Mark Alan Wright explained, “The anointing of a new king among the Maya began with a private ceremony held in the royal palace, attended by priests, scribes, and a select few elites. The public presentation of the new king occurred later at the temple, where he would be displayed in his full royal regalia.”4 This pattern matches Benjamin’s actions closely.

In fact, this Mesoamerican pattern is further followed in the setting of Mosiah’s public coronation. The people had gathered to the temple to hear King Benjamin, but because the crowd was so large, “king Benjamin could not teach them all within the walls of the temple, therefore he caused a tower to be erected, that thereby his people might hear the words which he should speak unto them” (Mosiah 2:7).

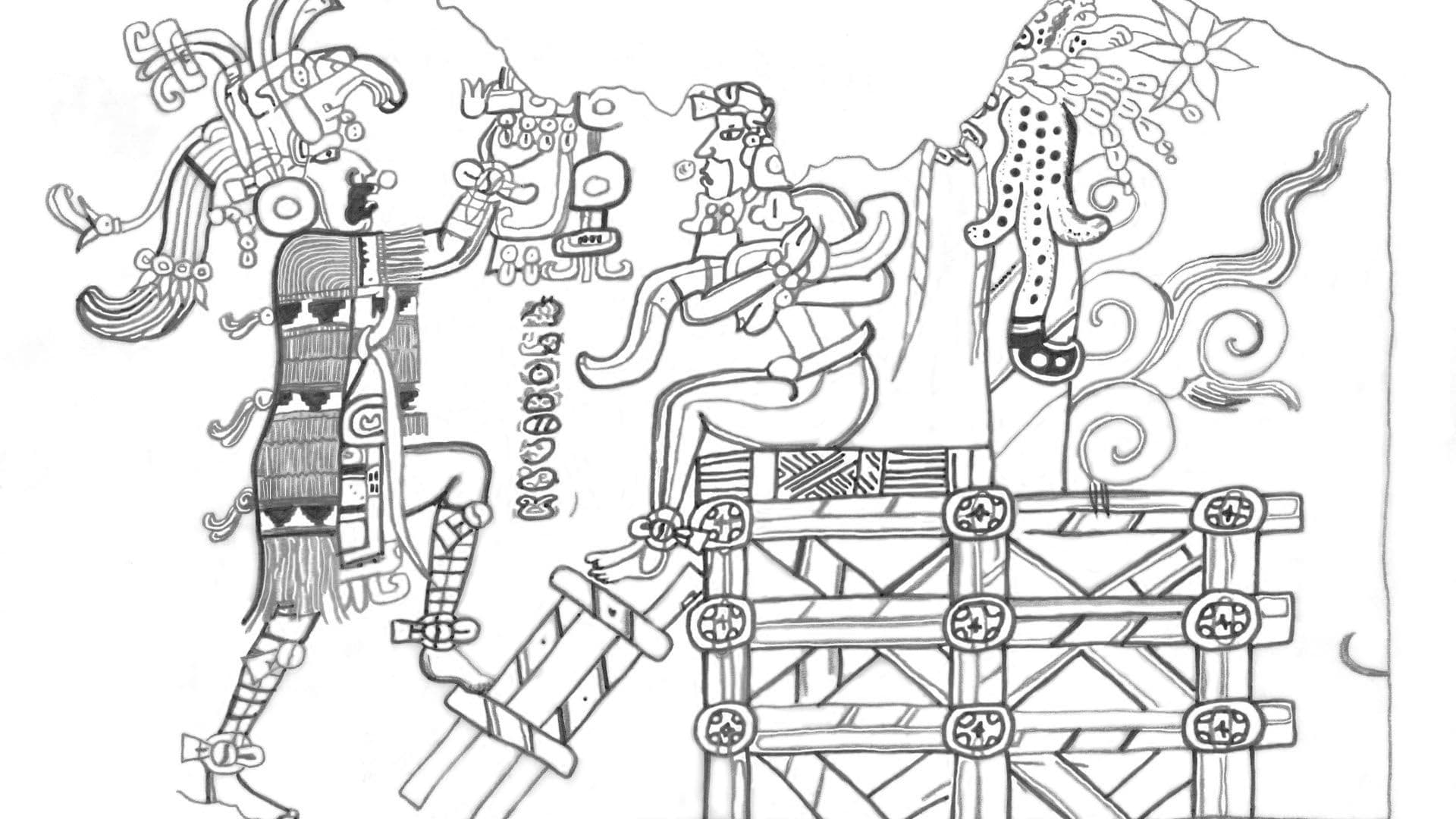

The construction of a wooden tower for a public coronation can likewise be found within an ancient American setting. Specifically, “on the murals of San Bartolo, Guatemala (ca. 100 BC) we see an enthronement ceremony wherein the ruler sits upon a wooden tower or scaffold to receive the emblems of rulership.” Furthermore, “the architectural layout of temple complexes effectively maximized acoustics, enabling speakers atop a temple to be seen and heard clearly throughout the plaza.”5

During Mesoamerican coronations, the king would perform a series of rituals. One of these, a bloodletting ritual, “required that blood [be] drawn from different and specific parts of the body.”6 It was believed that by shedding the king’s blood in this ritual fashion, doorways connecting the divine and earthly worlds would be opened and the king would receive visions and revelations about the divine realm and future events. Through these visions, the king could commune with divine beings (such as angels) and bring life to the world, which would also strengthen the king’s claim to be a divine being.7

Rather than performing a bloodletting ritual himself, as the “divine kings” of the Maya would, Benjamin insisted that he was not divine but taught about Jesus Christ, the true heavenly king, who would offer Himself as an atoning sacrifice. In this way, he effectively drew attention to Jesus’s blood instead of the earthly king’s: “[His] blood cometh from every pore,” and “salvation was, and is, and is to come, in and through the atoning blood of Christ, the Lord Omnipotent” (Mosiah 3:7, 18).

Regarding these teachings, Wright observed, “The Nephites, living among the larger Mesoamerican culture, would surely have been aware of the sacred nature of royal blood and the power it had to bring new life.”8 Furthermore, when performed at harvest festivals, Mayan coronations would have the king reenact a god’s descent to the underworld and triumphant resurrection—an act which Benjamin does not attribute to himself but, again, to Jesus Christ, who would do this through His Atonement.9

“King Benjamin, moreover, emphasized the fact that Christ was their Heavenly King (Mosiah 2:19) and that his blood had a power far beyond that of any earthly king—the power to atone for the sins of the world (Mosiah 3:11).”10 This was revealed to Benjamin as he conversed with an angel, which, although not occurring in a bloodletting ritual, itself would have nonetheless placed Benjamin as “an intermediary between the human and supernatural realms,” just as other Mesoamerican kings were considered to be.11

Another central aspect to divine kingship in ancient Mesoamerica was the king’s royal descent from a god. According to Wright, “for the ancient Maya, the right to rule clearly came by descent from the gods,” thereby allowing the king to receive “a portion of his ancestors’ divinity through birthright, and his legitimacy as ruler thus became firmly established in the minds of the people.”12

King Benjamin, however, does not claim his own descent from any divine being to strengthen his authority; to the contrary, Benjamin democratized this element of kingship, teaching that all the people could be considered descendants of the heavenly King” (Mosiah 2:19), and could all therefore be recipients of Christ’s blessings.13 By making covenants at the temple, the Nephites had all become “children of Christ, his sons, and his daughters; for behold, this day he hath spiritually begotten you” (Mosiah 5:7).

The Why

In the immediate context of King Benjamin’s speech, we learn that Benjamin viewed rulership far differently than did many of the neighboring civilizations with which the Nephites may have been familiar. Instead of focusing on power, political shrewdness, or popularity, Benjamin lived his life in service to others. In his speech, Benjamin emphasized that he had helped his people throughout his rule and ministry, thus focusing his people’s minds on Jesus Christ, our heavenly King, through both word and deed (see Mosiah 2:10–27).

As Benjamin taught powerfully, “there shall be no other name given nor any other way nor means whereby salvation can come unto the children of men, only in and through the name of Christ, the Lord Omnipotent” (Mosiah 3:17). Jesus is our heavenly King who, through His blood, allows us to enter His presence. This happens as we make the same covenants made by others anciently and as we, like Benjamin’s people, ask our heavenly King to “apply the atoning blood of Christ that we may receive forgiveness of our sins” (Mosiah 4:2).

In so pointing the people to Jesus Christ, Benjamin taught that all people can become like God, rejecting the belief that becoming divine was a right held exclusively by royalty. Wright observed,

The same rituals that were used to deify kings [in ancient Mesoamerica] were made available to all the saints. [Namely,] give everyone a divine ancestry through becoming a spiritually begotten child of Christ, give them a new name, rely on the blood sacrifice of their Heavenly King, put them under covenant at the temple, and have them arise from the dust and sit down upon thrones as heirs to celestial kingdom, whose glory is that of the sun.14

Such is the ultimate blessing for all who remain true and faithful to their covenants with God.

Mark Alan Wright, “Axes Mundi: Ritual Complexes in Mesoamerica and the Book of Mormon,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 12 (2014): 79–96.

Mark Alan Wright and Brant A. Gardner, “The Cultural Context of Nephite Apostasy,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 1 (2012): 25–55.

Mark Alan Wright, “Deification: Divine Inheritance and the Glorious Afterlife in the Book of Mormon and Ancient Mesoamerica” (paper, 2008 FAIR Conference, Sandy, UT, August 7, 2008.

Allen J. Christenson, “Maya Harvest Festivals and the Book of Mormon: Annual FARMS Lecture,” Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 3, no. 1 (1991): 1–31.

- 1. For a discussion on how ancient American temples were similar to the temple of Solomon, including as places of coronation, see Book of Mormon Central, “How Are Some Ancient American Temples Similar to the Temple of Solomon? (2 Nephi 5:16),” KnoWhy 716 (February 9, 2024).

- 2. Mark Alan Wright and Brant A. Gardner, “The Cultural Context of Nephite Apostasy,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 1 (2012): 42. See also Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 3:136.

- 3. See, for instance, Stephen D. Ricks, “Kingship, Coronation, and Covenant in Mosiah 1–6,” in King Benjamin's Speech: “That Ye May Learn Wisdom,” ed. John W. Welch and Stephen D. Ricks (Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies [FARMS], 1998), 233–275; Terrence L. Szink and John W. Welch, “King Benjamin’s Speech in the Context of Ancient Israelite Festivals,” in King Benjamin’s Speech, 147–223; John A. Tvedtnes, “King Benjamin and the Feast of Tabernacles,” in By Study and Also By Faith: Essays in Honor of Hugh W. Nibley, 2 vols., ed. John M. Lundquist and Stephen D. Ricks (Provo, UT: FARMS; Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1990), 2:197–237; Gregory Steven Dundas, Mormon's Record: The Historical Message of the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University, Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2024), 85–106; Book of Mormon Central, “Why Is the Theme of Kingship So Prominent in King Benjamin's Speech? (Mosiah 1:10),” KnoWhy 79 (April 15, 2016); Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did the Nephites Stay in Their Tents During King Benjamin’s Speech? (Mosiah 2:6),” KnoWhy 80 (April 18, 2016); Book of Mormon Central, “Why Does King Benjamin Emphasize the Blood of Christ? (Mosiah 4:2),” KnoWhy 82 (April 20, 2016). It may have been a Jubilee year; see Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Alma Wish to Speak “with the Trump of God”? (Alma 29:1),” KnoWhy 136 (July 5, 2016).

- 4. Mark Alan Wright, “Deification: Divine Inheritance and the Glorious Afterlife in the Book of Mormon and Ancient Mesoamerica” (paper, 2008 FAIR Conference, Sandy, UT, 2008), 9.

- 5. Mark Alan Wright, “Axes Mundi: Ritual Complexes in Mesoamerica and the Book of Mormon,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 12 (2014): 84–85. In note 15, Wright observes that “the date of the San Bartolo murals falls squarely in the time of Mosiah II, who reigned from ca. 124–91 BC, and whose reign was pronounced upon a tower by his father Benjamin.” Of course, these murals do not imply that Mosiah is the king depicted but rather show that this detail as recorded in the Book of Mormon fits an authentic ancient context.

- 6. Gardner, Second Witness, 3:152.

- 7. See Linda Schele and David Freidel, A Forest of Kings: The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya (New York, NY: William Morrow, 1990), 68–71.

- 8. Wright, “Deification,” 7.

- 9. For an excellent study on this matter, see Allen J. Christenson, “Maya Harvest Festivals and the Book of Mormon: Annual FARMS Lecture,” Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 3, no. 1 (1991): 1–31.

- 10. Wright, “Deification,” 7.

- 11. Wright, “Axes Mundi,” 84: “Ironically, by informing his people that the words he was delivering to them were given to him by an angel who literally ‘stood before’ him (Mosiah 3:2), he confirmed that he was in fact an intermediary between the human and supernatural realms, a defining characteristic of divine kings in the ancient world.” See also Wright, “Deification,” 7.

- 12. Wright, “Deification,” 9.

- 13. For more on the royal elements in being called a son or daughter of God, especially as it was employed by Benjamin to spiritually democratize the Nephites, see Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did King Benjamin Say That His People Would Be Sons and Daughters at God’s Right Hand? (Mosiah 5:7),” KnoWhy 307 (May 1, 2017); Book of Mormon Central, “How Did King Benjamin’s Speech Lead to Nephite Democracy? (Mosiah 29:32),” KnoWhy 301 (April 17, 2017). Receiving multiple throne names, such as that of God’s son, was also a common feature of both Old and New World coronations; here, Benjamin offers multiple throne names not for himself or his son Mosiah but rather for Jesus Christ. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Benjamin Give Multiple Names for Jesus at the Coronation of His Son Mosiah? (Mosiah 3:8),” KnoWhy 536 (October 17, 2019).

- 14. Wright, “Deification,” 11.