KnoWhy #797 | June 17, 2025

Why Did the Lord Invite People to Try to Produce Revelations Like Joseph Smith’s?

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

“Now, seek ye out of the Book of Commandments, even the least that is among them, and appoint him that is the most wise among you; or, if there be any among you that shall make one like unto it, then ye are justified in saying that ye do not know that they are true; but if ye cannot make one like unto it, ye are under condemnation if ye do not bear record that they are true.” Doctrine and Covenants 67:6–8

The Know

Early Church history is filled with powerful stories of faith, conversion, and miracles. Many of these impactful experiences stand behind the revelations given in the Doctrine and Covenants. Sometimes, however, people—including early supporters and converts, on occasion—sought to test or challenge the Prophet Joseph Smith. Although such attempts were often motivated by at least a degree of doubt or skepticism, they frequently yielded experiences or produced revelations that help support faith in Joseph Smith’s calling as a prophet.

For example, William McLellin joined the Church in the summer of 1831 after meeting David Whitmer and Martin Harris, two of the main Book of Mormon Witnesses, and hearing their testimonies.1 A couple of months later, McLellin met Joseph Smith for the first time at a conference held at Hiram, Ohio, near Kirtland. On that occasion, McLellin asked the Prophet for a revelation, which is now canonized as Doctrine and Covenants 66. In his contemporary journal, McLellin wrote, “This revelation [gives] great joy to my heart because some important questions were answered which had dwelt upon my mind with anxiety yet with uncertainty.”2 McLellin later turned against Joseph Smith and was excommunicated in May 1838, but even then, he could not deny that this revelation had addressed questions he had expressed to the Lord privately. In 1848, he explained:

I went before the Lord in secret, and on my knees asked him to reveal the answer to five questions through his Prophet, and that too without his [Joseph’s] having any knowledge of my having made such request. I now testify in the fear of God, that every question which I had thus lodge in the ears of the Lord of Sabbaoth, were answered to my full and entire satisfaction. I desired it for a testimony of Joseph’s inspiration. And I to this day consider it to me an evidence which I cannot refute.3

McLellin had already received his own powerful witness of the truth of the Restoration, but he nonetheless sought to test the Prophet when he first met him; the results of that test of Joseph’s prophetic prowess were so impressive that even after McLellin had become estranged from Joseph and the Saints, he had to concede that the revelation remained “evidence which I cannot refute.”4

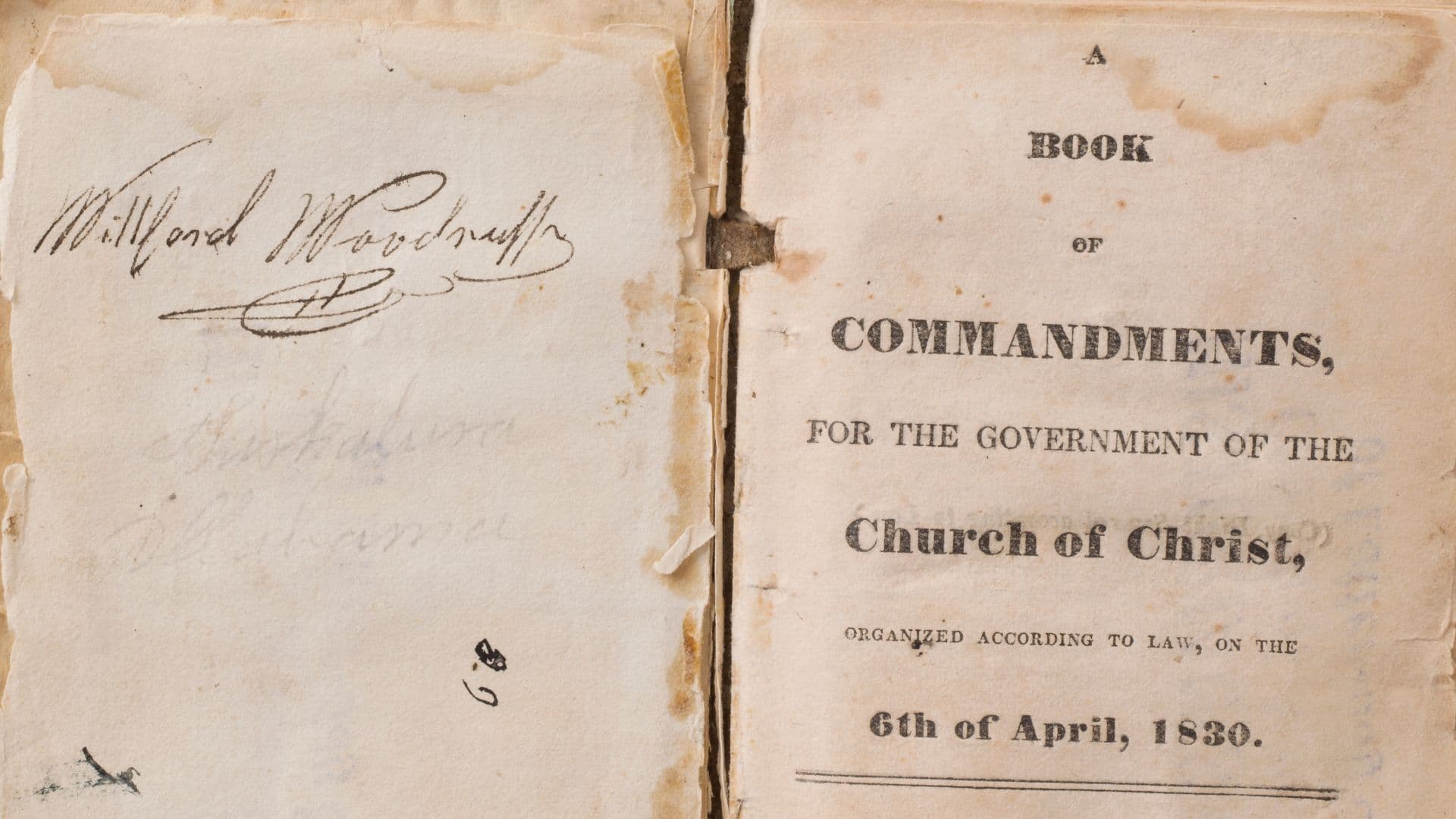

A couple of days after receiving the revelation, at a conference on November 1, 1831, McLellin was involved in a second incident that produced evidence of Joseph Smith’s divine inspiration. The elders of the conference had been promised a special witness to the truth of the revelations compiled for publication in the forthcoming Book of Commandments, which witness they were then expected to bear to the world of the book’s truth. Yet some questioned whether the language of the revelations was polished, elevated, and sophisticated enough to represent the voice of God.5 As a result, Joseph Smith received the revelation now canonized as Doctrine and Covenants 67.

In this revelation, the Lord explained that “fears in [the elders’] hearts” prevented them from receiving the witness they had previously been promised (v. 3). The Lord then invited anyone present at the conference to craft a comparable revelation:

Now, seek ye out of the Book of Commandments, even the least that is among them, and appoint him that is the most wise among you; or, if there be any among you that shall make one like unto it, then ye are justified in saying that ye do not know that they are true; but if ye cannot make one like unto it, ye are under condemnation if ye do not bear record that they are true. (Doctrine and Covenants 67:6–8)

In response to this challenge, McLellin took up the pen, with assistance from others, to attempt to write a similarly impressive revelation. Joseph Smith would later explain,

Wm E. McLellin, as the wisest man in his own estimation, having more learning than sense, endeavored to write a commandment like unto one of the least of the Lord’s . . . but failed. . . . The elders, and all present, that witnessed this vain attempt of a man to imitate the language of Jesus Christ, renewed their faith in the fulness of the gospel and in the truth of the commandments and revelations which the Lord had given to the church through my instrumentality; and the elders signified a willingness to bear testimony of their truth to all the world.6

As Stephen E. Robinson and H. Dean Garrett have explained, “When William McLellin, with the help of others present, failed to write anything that sounded convincingly like a revelation from God, the issue was settled. Unaided by the Spirit, not even the brightest among them could write a convincing revelation, even though they knew themselves to be much better writers than Joseph Smith.”7

The Why

Sections 66 and 67 of the Doctrine and Covenants were received only a few days apart. They represent two different kinds of challenges as people tested Joseph Smith’s ability to receive and dictate revelation from heaven. With the first, William McLellin put the Prophet Joseph to the test through a private request in prayer to the Lord; with the second, McLellin put himself to the test to see if he could write a convincing revelation without inspiration from heaven. By McLellin’s own testimony, Joseph passed his test with flying colors while McLellin failed. Combined, these results serve as powerful evidence that Joseph Smith was truly a prophet who spoke for the Lord.

Certainly, the Lord knows well that people need reassurances, and He wants to encourage them in their efforts to believe. Often in scripture, the Lord invites people to ask, seek, and knock, so that He can reveal unto them the truthfulness of the words of His prophets. In one case, in Numbers 16, people in the camp of Israel murmured against Moses and Aaron, saying, “Is it a small thing that thou hast brought us up out of [Egypt]” (Numbers 16:13). Meeting that cocky attitude, Moses challenged Korah and his followers to bring all their incense burners before the Lord as part of a test whereby Moses made sure they knew “that the Lord hath sent me to do all these works; for I have not done them of mine own mind” (Numbers 16:28). In vindicating His prophet, the Lord showed the people that what Moses had done was not a small thing and that the power of the Lord was far beyond their imagination. Just as the Lord had vindicated His ancient prophets, so He welcomed the opportunity in 1831 to make it clear that the written revelation that His prophet Joseph Smith had brought forth was no simple thing that just anyone could do.

This, of course, does not mean that either Moses or Joseph Smith was perfect or that their revelations could not benefit from some good editing. Indeed, the revelations as printed today in the Doctrine and Covenants have undergone editing to help them read more smoothly and to clarify points that may otherwise be unclear to modern readers who may be unaware of nuances from the context of the revelations.8 As Robinson and Garrett have noted,

The question was whether better educated writers could on that occasion, November 1831, unitedly write a more convincing revelation than any of Joseph’s. Is the inspired quality of a revelation found in what it says or in how it says it? Is the divinity in the message or in its vocabulary and punctuation? The elders present at the November conference established to their own satisfaction that it was the former. With all their superior education, polish, and literary skills, they could not duplicate the divine element that they sensed in the revelations of the Prophet Joseph Smith.9

Joseph Smith said, “It was an awful responsibility to write in the name of the Lord,” and no amount of literary flourish or editorial polish could make up for a lack of inspiration when carrying out this weighty responsibility.10

In the aftermath of these events, McLellin initially strived to follow the counsel he received from the Lord in Doctrine and Covenants 66, but like many of the ancient Israelites and all of us, McLellin struggled to consistently obey.11 Yet these formative experiences impressed upon his mind the legitimacy of Joseph’s claim to revelation. In August 1832, even as he had struggled to live by the revelations he had been given, he testified, “Joseph Smith is a true Prophet or Seer of the Lord and that he has power and does receive revelations from God, and that these revelations when received are of divine Authority in the church of Christ.”12 Even after he was excommunicated, as Steven C. Harper observed, McLellin “spent the rest of his life struggling to resolve the dissonance between his unshaken testimony and his unwillingness to repent.”13

Matthew C. Godfrey, “William McLellin’s Five Questions,” in Revelations in Context: The Stories Behind the Sections of the Doctrine and Covenants, ed. Matthew McBride and James Goldberg (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2016), 137–41.

Casey Paul Griffiths, Scripture Central Commentary on the Doctrine and Covenants, 4 vols. (Cedar Fort; Scripture Central, 2024), 2:261–67.

Steven C. Harper, Making Sense of the Doctrine and Covenants (Deseret Book, 2008), 229–36.

Stephen E. Robinson and H. Dean Garrett, A Commentary on the Doctrine and Covenants, 4 vols. (Deseret Book, 2000–2005), 2:226–41.

- 1. For background on these experiences, see William G. Hartley, “The McLellin Journals and Early Mormon History,” in The Journals of William E. McLellin, 1831–1836, ed. Jan Shipps and John W. Welch (BYU Studies; University of Illinois Press, 1994), 264–67; Steven C. Harper, “McLellin, William E.,” in Doctrine and Covenants Reference Companion, ed. Dennis L. Largey and Larry E. Dahl (Deseret Book, 2012), 396.

- 2. William McLellin, journal, October 29, 1831, in Shipps and Welch, Journals of William E. McLellin, 46.

- 3. William McLellin, in Ensign of Liberty 4, January 1848, as cited in Shipps and Welch, Journals of William E. McLellin, 57n52.

- 4. McLellin viewed the Book of Mormon in a similar manner and defended its inspiration and divinity even when he was most antagonistic towards Joseph Smith and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. See Scripture Central, “Why Did William E. McLellin Call the Book of Mormon the ‘Apple of My Eye’? (Doctrine and Covenants 66:1),” KnoWhy 611 (July 1, 2021).

- 5. For historical background, see Stephen E. Robinson and H. Dean Garrett, A Commentary on the Doctrine and Covenants, 4 vols. (Deseret Book, 2000–2005), 2:232–33; Steven C. Harper, Making Sense of the Doctrine and Covenants (Deseret Book, 2008), 233–36; Casey Paul Griffiths, Scripture Central Commentary on the Doctrine and Covenants, 4 vols. (Cedar Fort; Scripture Central, 2024), 2:261–62.

- 6. “History, 1838–1856, volume A-1 [23 December 1805–30 August 1834],” p. 162, The Joseph Smith Papers.

- 7. Robinson and Garrett, Commentary on the Doctrine and Covenants, 2:234–35.

- 8. Readers can readily compare the current canonized versions of each revelation to the earliest available manuscript copy in Joseph Smith’s Revelations: A Doctrine and Covenants Study Companion from the Joseph Smith Papers (Church Historian’s Press, 2020).

- 9. Robinson and Garrett, Commentary on the Doctrine and Covenants, 233.

- 10. “History, 1838–1856, volume A-1 [23 December 1805–30 August 1834],” p. 162, The Joseph Smith Papers.

- 11. See Harper, Making Sense, 230–32.

- 12. William McLellin, journal, August 4, 1832, in Shipps and Welch, Journals of William E. McLellin, 84.

- 13. Harper, Making Sense, 232.