KnoWhy #747 | August 22, 2024

Why Did the King-Men Suddenly and Violently Seek Power?

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

“Now those who were in favor of kings were those of high birth, and they sought to be kings; and they were supported by those who sought power and authority over the people.” Alma 51:8

The Know

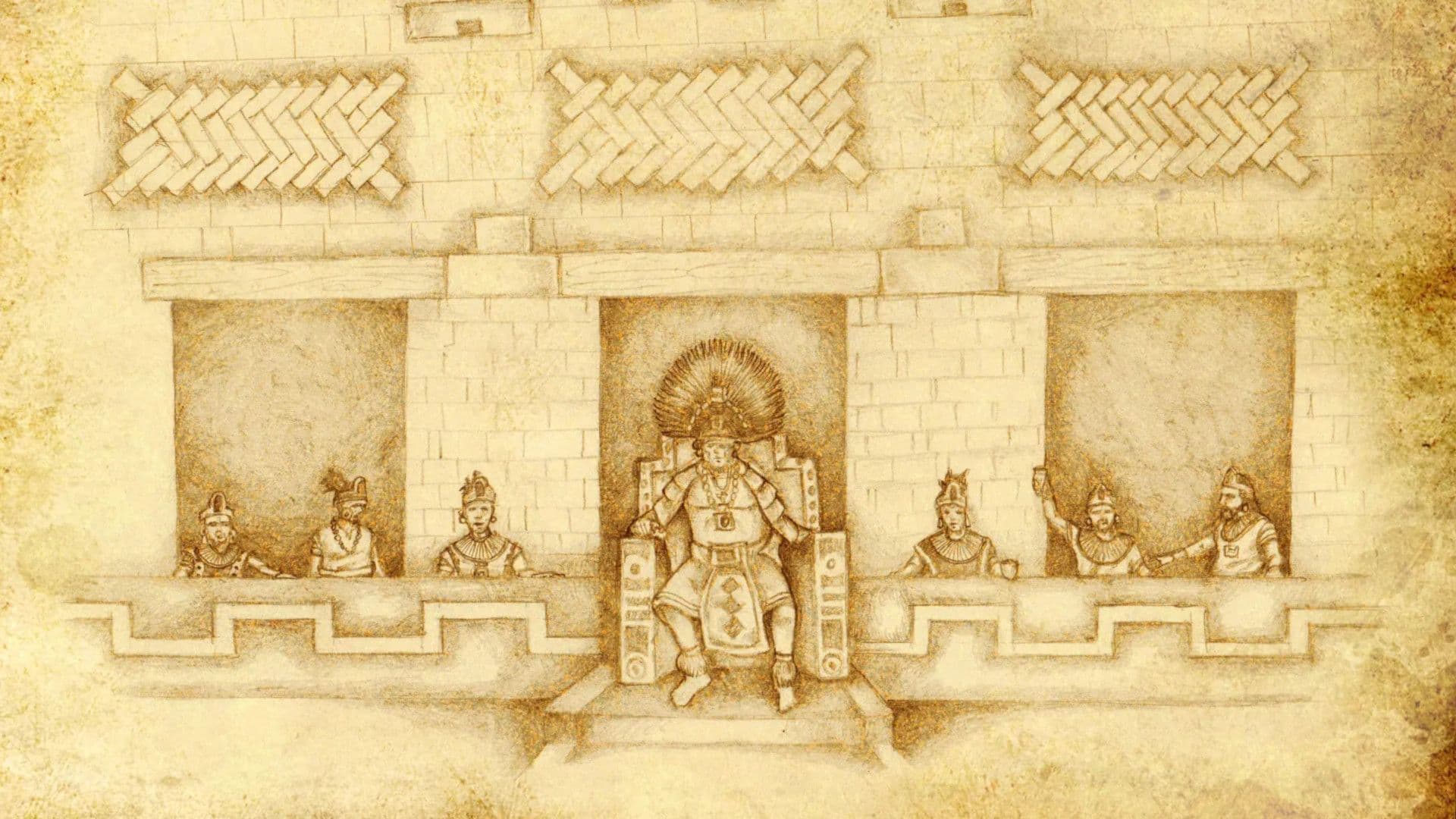

During a critical time in Nephite history, as the Nephites were at war with the Lamanites and Nephite dissenters led by Amalickiah, an internal dispute was started by a group called the king-men. It divided Nephite attention from the war and cost them a great deal. Nephihah had been the chief judge, but he died in about 68 BC. Soon after his father’s death, Pahoran “was appointed to fill the judgment-seat, in the stead of his father,” but this appointment was not universally accepted (Alma 50:39). According to Mormon, “there were a part of the people who desired that a few particular points of the law should be altered,” and when the new, young judge Pahoran denied their request, they became angry, seizing a moment of weakness as the Nephite people adjusted operation under a new ruler (51:2–4). Mormon calls this dissident group of people “king-men, for they were desirous … to establish a king over the land” (51:5). Their bid, however, was rejected by the voice of the people, and Pahoran remained the chief judge (see 51:7).

The king-men did not take this defeat lightly. When the “king-men had heard that the Lamanites were coming down to battle against them, they were glad in their hearts; and they refused to take up arms, for they were so wroth with the chief judge” (Alma 51:13). This distraction and setback allowed the Lamanites to capture various cities while Moroni focused on subduing the king-men. Later, the king-men attempted a somewhat more successful coup, causing Pahoran to flee to the land of Gideon until he and Moroni could eventually reclaim Zarahemla (see 61:3–5).

Several clues in the book of Alma offer potential insight into the origin of the king-men and their desire for power. According to Mormon, “those who were in favor of kings were those of high birth, and they sought to be kings; and they were supported by those who sought power and authority over the people”; furthermore, they “professed the blood of nobility,” leading to attitudes of stubbornness and pride (Alma 51:8, 21; emphasis added). When we take in the wider context of rebellion among the Nephites, we see that these claims to nobility were likely more than just wishful thinking and instead reflected the group’s heritage as descendants of Mulek.

In Helaman 6:10, it is revealed that Mulek, who was previously mentioned as the founder of the people of Zarahemla, was a son of King Zedekiah (the son of King Jehoiakim), the king of Judah at the time that Lehi and Nephi fled Jerusalem. As such, descendants of Mulek, who thought Mulek was the only surviving royal heir, could reasonably have claimed that they were the last and only descendants of the Davidic dynasty and thus were the heirs of the covenant the Lord had made with David centuries earlier: “And thine house and thy kingdom shall be established for ever before thee: thy throne shall be established for ever” (2 Samuel 7:16). Indeed, Mulek’s name is derived from the Hebrew root mlk, meaning “king” or “to reign.”1 Many of the would-be kings in the book of Alma similarly bore names that appear to be based on this root, reflecting their desire for kingship and perhaps also indicating their Mulekite ancestry.

The first major conflict with such king-men arose in the fifth year of the reign of the judges when a man named Amlici drew “away much people after him; even so much that they began to be very powerful; and they began to endeavor to establish Amlici to be a king over the people” (Alma 2:2). As Matthew L. Bowen has observed, this passage may contain an inherent wordplay with the Hebrew verb mālak, meaning “to become king” or “reign [as king].”2 This wordplay would have been more obvious in Hebrew, for Amlici’s name (like Mulek’s name) is probably derived from the Hebrew root mlk.3 If Amlici was indeed a descendant of Mulek, that could explain why his claims to the throne had soon managed to gain some popular support.4

It is possible that the Amalekites may have also been Mulekites who also had dissented, as they are reported as having built a city named Jerusalem in the land of Nephi (21:1–4).5 As Val Larsen and Lyle H. Hamblin have noted, this would be the ideal name for a city built by the descendants of the king of Jerusalem.6 Hamblin has also proposed that the later dissenter Amalickiah may have had Mulekite lineage in addition to his stated Nephite and Zoramite heritage. All this could explain how he was able to gain so much popularity among the Lamanites.7

The king-men of Alma 51 and 61 could likewise be seen in this same pattern of Mulekite rebellion against the reign of judges, the institution of which may have been viewed by Mulekites as “a political regression that would dishonor both king David’s legacy and his present descendants, the Mulekites.”8 Thus, as John W. Welch has observed, the “Mulekitish people may also have surfaced again, a few years later, in the form of the persistent royalist undercurrent of the so-called king-men (51:5).”9 The underlying Hebrew for “king-men” would likely be ʿam hamelek, meaning “people [‘am] of the king [mlk].” This could offer another instance of wordplay on the name Mulek (mlk) to designate the leader’s rebellious descendants who sought to reinstate the Davidic dynasty.10

Furthermore, as John A. Tvedtnes has observed, the designation of king-men being “compelled to hoist the title of liberty upon their towers, and in their cities” may be a hint that these were not just a scattered party but rather a tribal group like the Mulekites: “If this means that they were settled in specific cities, then they are more likely a tribal group than a political faction with representation throughout the Nephite lands” (Alma 51:20; emphasis added).11

It is also noteworthy that it is only after Alma is appointed as the first chief judge that political turmoil again rises to the forefront of Nephite history. This can probably be explained by the actions of King Mosiah or King Benjamin, who “would likely have arranged a marriage between one or more of his children and those of Zarahemla” in order to better unite the Nephites and Mulekites.12 Should the Nephite and Mulekite dynasties have merged in this fashion, it would also explain why the people were willing to have Aaron be their next king without any reported difficulties (see Mosiah 29:1–2). Thus, it was only when the throne and Davidic dynasty had seemingly been abandoned by the Nephites that attempts to reinstate it began.

The Why

The rebellion and even the attempted coup of the king-men helps provide an interesting clue to key aspects of the Book of Mormon culture and society. This includes the social complexities of Nephite polity in the first generation after the transition from kings to judges and the tense situation King Mosiah was navigating. Even with Mosiah’s inspired solution, multiple groups believed they knew better than the prophet and could provide better leadership than the system Mosiah established.13

We can also better understand why Moroni taught, “The inward vessel shall be cleansed first, and then shall the outer vessel be cleansed also” (Alma 60:23). As Moroni had witnessed through the rebellion of the king-men and perhaps through other rebellions among the Nephites when he was younger, the “inner part” of the population could become seriously contaminated quite easily—simply by idleness and dereliction of duty. If the Nephites wanted to obtain God’s blessings, they had to first strive to be worthy inwardly of those blessings.14

Their inner vessels, moreover, had become filthy primarily because of pride. Mormon notes that this sin was one of the biggest stumbling blocks the king-men faced, requiring Moroni’s army “to pull down their pride and their nobility and level them with the earth” (Alma 51:17). Had it not been for the king-men’s pride, the Nephites would not have faced as critical a situation as they did during the war with Amalickiah. This divided the Nephite forces, preventing them from being one as the Lord has commanded His people (see Doctrine and Covenants 38:27). Modern readers can take these lessons to heart as we seek to remain humble and be unified with the Lord’s will and with one another, allowing our inner vessels to be clean so that we can receive God’s blessings.

Lyle H. Hamblin, “Proper Names and Political Claims: Semitic Echoes as Foundations for Claims to the Nephite Throne,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 60 (2024): 409–444.

Brant A. Gardner, Engraven upon Plates, Printed upon Paper: Textual and Narrative Structures of the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2023), 113–122.

Val Larsen, “In His Footsteps: Ammon₁ and Ammon₂,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 3 (2013): 85–113.

John A. Tvedtnes, “Book of Mormon Tribal Affiliation and Military Castes,” in Warfare in the Book of Mormon, ed. Stephen D. Ricks and William J. Hamblin (Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies [FARMS]; Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1990), 296–326.

- 1. Stephen D. Ricks, Paul Y. Hoskisson, Robert F. Smith, and John Gee, Dictionary of Proper Names and Foreign Words in the Book of Mormon (Orem, UT: Interpreter Foundation; Salt Lake City: Eborn Books, 2022), s.v. “Mulek.”

- 2. Matthew L. Bowen, “The Faithfulness of Ammon,” Religious Educator 15, no. 2 (2014): 69.

- 3. Ricks et al., Dictionary of Proper Names and Foreign Words, s.v. “Amlici.”

- 4. Lyle H. Hamblin, “Proper Names and Political Claims: Semitic Echoes as Foundations for Claims to the Nephite Throne,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 60 (2024): 425–426: “Recognizing Amlici as a politician who tapped into strong underlying Mulekite claims, some of which had likely been contested before, such as in Benjamin’s day (Words of Mormon 1:16), allows for rapid political developments.”

- 5. It is also possible that the Amalekites and Amlicites were the same group of people, based on scribal and textual evidence from the printer’s manuscript of the Book of Mormon. Scripture Central, “How Were the Amlicites and Amalekites Related? (Alma 2:1–5),” KnoWhy 109 (May 27, 2016). However, based on the timing each appear in the text of the Book of Mormon itself, it is also possible that they were two distinct groups. Benjamin McMurtry, “The Amlicites and Amalekites: Are They the Same People?” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 25 (2017): 269–281. Book of Mormon scholar Brant A. Gardener has likewise argued that “Mormon gave apostate groups a generic designation of Amlicite/Amalekite with at least the implied meaning of apostate-of-Mulekite-lineage.” Brant A. Gardner, Engraven upon Plates, Printed upon Paper: Textual and Narrative Structures of the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2023), 117; see also John W. Welch, The Legal Cases in the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press; Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2008), 212–213n2: “Just as the name Gadianton was used to refer to several similar robber groups under different leaders, the name Amlicites seems to have been used to identify several dissident king groups.”

- 6. Val Larsen, “In His Footsteps: Ammon₁ and Ammon₂,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 3 (2013): 100–101; Hamblin, “Proper Names and Political Claims,” 428.

- 7. Hamblin, “Proper Names and Political Claims,” 431: “The tribal identity of Amalickiah seems to indicate political opportunism. Amalickiah is referred to as a ‘Nephite by birth’ (Alma 49:25), and his brother Ammoron defines himself in a letter to Moroni as a ‘descendent of Zoram, whom [Nephite] fathers pressed and brought out of Jerusalem’ (Alma 54:23). To what extent their lineage was mixed with Mulekites is not specified but is likely from the M-L-K root in the first name.” It is also possible, however, that Amalickiah was not a Mulekite but was given a name derived from mlk by Mormon to highlight Amalickiah’s role in the narrative. Mulekite claims could have synthesized with Lamanite and Gadianton claims of governing rights and may have used similar rhetoric. Alma 54:17–18; 3 Nephi 3:10.

- 8. Hamblin, “Proper Names and Political Claims,” 420.

- 9. Welch, Legal Cases in the Book of Mormon, 212.

- 10. While John L. Sorenson, “The ‘Mulekites,’” BYU Studies 30, no. 3 (1990): 17, argues that it is likely the king-men were descendants of Mosiah I, Benjamin, or Mosiah II, the Mulekite connection is more probable, as argued by Hamblin, Larsen, and Tvedtnes above. If the Mosiah dynasty had indeed intermixed with Mulekites, the claims could have been compounded.

- 11. John A. Tvedtnes, “Book of Mormon Tribal Affiliation and Military Castes,” in Warfare in the Book of Mormon, ed. Stephen D. Ricks and William J. Hamblin (Provo, UT: Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies [FARMS]; Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1990), 299. Towers were also typical of private Mesoamerican family compounds, as discussed in John L. Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex: An Ancient American Book (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2013), 323–325; Kerry Hull, “War Banners: A Mesoamerican Context for the Title of Liberty,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 24 (2015): 106–108. See also Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytic and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 6 vols (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007) 5:121.

- 12. Larsen, “In His Footsteps,” 93. It is also possible that the “false Christs” Benjamin faced in Words of Mormon 1:15 may have also been contenders for the throne, as the word anointed (or messiah in Hebrew, from which the name Christ comes) was often used to describe the king.

- 13. See Welch, Legal Cases in the Book of Mormon, 215–218, for a discussion on this period of transition.

- 14. For a discussion on cleansing the inner vessel in Moroni’s teachings, see Scripture Central, “Why Did Moroni Refer to Vessel Impurity in Condemning the Central Government? (Alma 60:23),” KnoWhy 169 (August 19, 2016).