KnoWhy #574 | August 20, 2020

Why Did Pahoran, Paanchi, and Pacumeni have Such Similar Sounding Names?

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

“Now these are their names who did contend for the judgment-seat, who did also cause the people to contend: Pahoran, Paanchi, and Pacumeni.” Helaman 1:3

The Know

A general rule for fiction writing is that the authors should choose names that are accessible to their readers. “Readers must be able to pronounce them, differentiate them, remember them, and keep them straight.”1 To aid readability, fiction writers are typically “careful to avoid having two significant characters whose names begin with the same sound.”2 Of course, real life does not always avoid people with similar (or even identical) names being brought together, and historical naming patterns differ from those found in fiction.3 Thus, it should come as no surprise that the Book of Mormon, as an ancient historical record, frequently breaks this cardinal rule of modern fictional naming practices.4

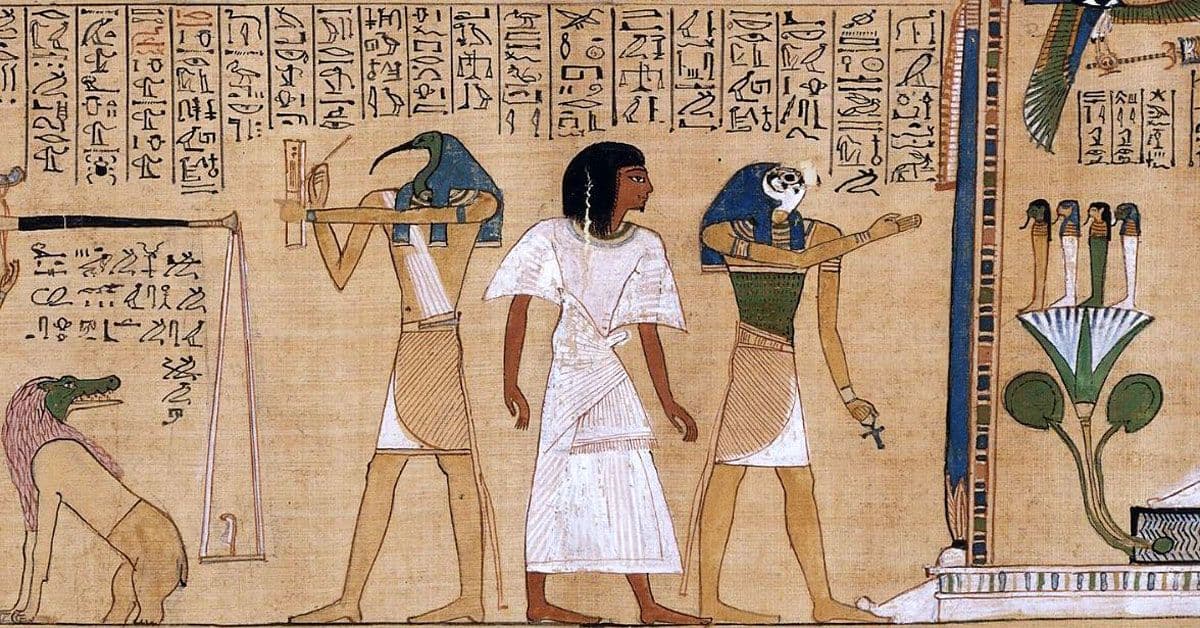

For example, at the beginning of the book of Helaman, readers encounter a confusing cluster of three similar sounding names: two men (a father and a son) named Pahoran, as well as Pahoran’s two brothers Paanchi and Pacumeni (Helaman 1:2–3). Although this constellation of names would be an unlikely choice for a good fiction writer, Hugh Nibley noticed that it rings true for a record written in “reformed Egyptian” (Mormon 9:32–34). “A striking coincidence,” Nibley noted, “is the predominance among both Egyptian and Nephite judge names of the prefix Pa-. In late Egyptian this is extremely common.”5 Each of the names, and not just the initial pa- (Egyptian pꜢ- = “the”) prefix, bears striking resemblance to Egyptian names.

Pahoran (or Parhoron/Pahoron)6

Egyptian/Canaanite administrative correspondence written during the 14th century BC frequently mentions an official named Paḫura (also spelled Piḫura, Piḫuru, and Puḫuru), the cuneiform rendering of the Egyptian name pꜢ-ḫr-ꜣn (Pa-ḫer-an, according to Nibley) or pꜢ-ḫꜣry.7 The name means “the Syrian” or “the Hurrian.”8 Hence we know that Paḫura was “an Egyptian governor (rabu) of Syria.”9

Paanchi

Nibley and other scholars have connected Paanchi to the Egyptian name pꜢ-ꜥnḫ (spelled Paiankh, Pianchi, and Paankh, according to Nibley, or commonly Piankh or Pianch today).10 It was the name of a high priest of the god Amun, who was also a general in the 21st Dynasty (ca. 1069–945 BC),11 and perhaps also the name of an important Egyptian pharaoh from the 25th Dynasty (ca. 747–656 BC).12 The name is generally taken to mean “the living one,” and can be a deity title, like “the living God” (cf. Moses 5:29).13 Since the word ankh (ꜥnḫ) primarily means “life” or “to live,” its hieroglyph became a very common symbol for everlasting life. In addition, ankh can also mean “oath” or “to swear.” Thus, linguist Matthew L. Bowen has alternatively proposed the meaning “He [the god] is my (life-)oath” for pꜢ-ꜥnḫ-ỉ.14

Pacumeni

Nibley and others have compared Pacumeni to the Egyptian Pakamen (pꜢ-kmn), meaning “the blind man.”15 Nibley also suggested Pamenech (pꜢ-mnkh), which is sometimes rendered as Pachomios in Greek.16 Kumen or cumen is also a common element in other Book of Mormon names,17 including the city of Cumeni mentioned during the major war in the book of Alma (Alma 56:14; 57:7–34). Adding the Egyptian pꜢ- to this name to form Pacumeni could mean “the Cumenite,” perhaps suggesting ties to that city.18 In Hebrew, kmn means “to hide; to hide up,” and thus another possibility is “the one who is hidden away.”19

The Why

A knowledge of this background strengthens the credibility of the Book of Mormon. The Egyptian nature of these names is so compelling that even the eminent 20th century non-Latter-day Saint scholar William F. Albright was impressed. In a letter, Albright expressed surprise “that there are two Egyptian names, Paanch[i] and Pahor(an) which appear together in the Book of Mormon in close connection with a reference to the original language as being ‘Reformed Egyptian.’”20

In addition, these three Egyptian names are especially fitting for the narrative setting of Helaman 1:1–10. The official nature of these names adds a suitable context to the story of the demise of the sons of Pahoran, who had been the Nephite chief judge. As Nibley observed, “Such family rivalry for the office of high priest is characteristic of the Egyptian system, in which the office seems to have been hereditary not by law but by usage.”21

Nibley drew particular attention to an Egyptian named Paanchi (Piankh), whose father (named Kherihor or Ḥerihor [Egyptian: ḥry-ḥr], cf. Korihor) was involved “in a priestly plot [that] set himself up as a rival of Pharaoh himself, while his son Paanchi actually claimed the throne.”22 Thus, the name Piankh shows up in Egyptian texts in close association with an attempt to usurp the throne, just as Paanchi in the Book of Mormon rejects the voice of the people and seeks to usurp the judgment-seat (Helaman 1:5–8).

More recently, Matthew L. Bowen, an expert in Semitic and Egyptian languages, has drawn additional attention to the fact that Paanchi’s rebellion initiates a series of events that culminates in his followers entering into secret covenants and oaths, “swearing by their everlasting Maker” (Helaman 1:11). Thus, this narrative involving Paanchi (pꜢ-ꜥnḫ-ỉ) seems to invoke or allude to the subtle meanings of ankh (not just life, live; but also oath, swear) and their association with oaths and swearing on the life of a deity.23

While the story of a rivalry for the judgment-seat between three brothers from a ruling-elite family with similar sounding names (Pahoran, Paanchi, and Pacumeni) may not be good fiction writing, Mormon apparently appreciated the value of these names at several levels, and that is why he purposefully included them in his record. These names and the narrative in Helaman 1 are arguably more true to life and consistent with the ancient Egyptian origins of the Book of Mormon than any fiction writer in 1829 could have hoped.

Book of Mormon Onomasticon, s.v. PAHORAN, s.v. PAANCHI, s.v. PACUMENI.

Sharon Black and Brad Wilcox, “188 Unexplainable Names: Book of Mormon Names No Fiction Writer Would Choose,” Religious Educator 12, no. 2 (2011): 118–133.

Matthew L. Bowen, “‘Swearing by Their Everlasting Maker’: Some Notes on Paanchi and Giddianhi,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 28 (2018): 159–164.

Hugh Nibley, Lehi in the Desert/The World of the Jaredites/There Were Jaredites (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1988), 22–24.

Hugh Nibley, Approaching the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1988), 282–284.

- 1. Sharon Black and Brad Wilcox, “188 Unexplainable Names: Book of Mormon Names No Fiction Writer Would Choose,” Religious Educator 12, no. 2 (2011): 122.

- 2. Black and Wilcox, “188 Unexplainable Names,” 122. See also Sharon Black and Brad Wilcox, “Sense and Serendipity: Some Ways Fiction Writers Choose Character Names,” Names: A Journal of Onomastics 59, no. 3 (2011): 152–163.

- 3. Brad Wilcox, Bruce L. Bowen, Wendy Baker-Smemoe, Sharon Black, and Justin Bray, “Identifying Authors by Phonoprints in Their Characters’ Names: An Exploratory Study,” Names: A Journal of Onomastics 61, no. 2 (2013): 101–121. This method is applied to the Book of Mormon in Brad Wilcox, Bruce L. Bowen, Wendy Baker-Smemoe, Sharon Black, and Justin Bray, “Comparing Book of Mormon Names with Those Found in J.R.R. Tolkien’s Works: An Exploratory Study,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 30 (2018): 105–124; Brad Wilcox, Bruce L. Bowen, Wendy Baker-Smemoe, Sharon Black, and Justin Bray, “Comparing Phonemic Patterns in Book of Mormon Personal Names with Fictional and Authentic Sources: An Exploratory Study,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 33 (2019): 105–122.

- 4. See Black and Wilcox, “188 Unexplainable Names,” 122–123.

- 5. Hugh Nibley, Lehi in the Desert/The World of the Jaredites/There Were Jaredites (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1988), 23. See also Hugh Nibley, Approaching the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1988), 282.

- 6. In the extant portion of the original manuscript, the name Pahoran is spelled with an o as the final vowel, and sometimes with an r before the h (i.e., Pahoron or Parhoron). For analysis of these variant spellings, see Royal Skousen, Analysis of Textual Variants of the Book of Mormon, 6 vols., 2nd ed. (Provo, UT: FARMS and BYU Studies, 2017), 4:2737–2739.

- 7. See Nibley, Lehi in the Desert, 22, 27–28; Nibley, Approaching, 284; Book of Mormon Onomasticon, s.v. PAHORAN. See EA 57, 117, 122, 123, 132, 189, 190, 207, and 208 in William L. Moran, ed. and trans., The Amarna Letters (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992); Anson F. Rainey, trans., The El-Amarna Correspondence: A New Edition of the Cuneiform Letters from the Site of El-Amarna based on Collations of all Extant Tablets, ed. William Schniedewind and Zipora Cochavi-Rainey (Boston, MA: Brill, 2015). For the list full list of spelling variations, see Moran, p. 383. Note that in some instances (e.g., EA 117, 132), Rainey has Pawura instead of Paḫura.

- 8. See Moran, Amarna Letters, 383; cf. Leonard Lesko, A Dictionary of Late Egyptian, 2nd ed. (Providence, RI: B.C. Scribe Publications, 2002), 1:349; Book of Mormon Onomasticon, s.v. PAHORAN, s.v. PACUMENI. See also Robert F. Smith, “Egyptianisms in the Book of Mormon” (n.p., in BMC staff possession), 38.

- 9. Nibley, Lehi in the Desert, 22.

- 10. Nibley, Lehi in the Desert, 22–23, 27; Nibley, Approaching, 283–284. T. Eric Peet, Egypt and the Old Testament (Liverpool and London: University Press of Liverpool and Hodder & Stoughton, 1922), 169 spells it Piankhi. See also Book of Mormon Onomasticon, s.v. PAANCHI; Matthew L. Bowen, “‘Swearing by Their Everlasting Maker’: Some Notes on Paanchi and Giddianhi,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 28 (2018): 159; Robert F. Smith “Some ‘Neologisms’ from the Mormon Canon,” 1973 Conference on the Language of the Mormons, May 31, 1973 (Provo: BYU Language Research Center, 1973), 65; Smith, “Egyptianisms,” 39.

- 11. Karl Jansen-Winkeln, “Das Ende des Neuen Reiches,“ Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache 119 (1992): 22–26; John Taylor, “The Third Intermediate Period (1069–644 BC),” in The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, ed. Ian Shaw (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2000), 331, 333.

- 12. The name of this king is typically rendered Piye in more modern translations (see e.g. Robert K. Ritner, The Libyan Anarchy: Inscriptions from Egypt’s Third Intermediate Period [Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature, 2009], 1, 7, 492), but Piankhy is also a possible reading and was used commonly in older translations. See Ronald J. Leprohon, The Great Name: Ancient Egyptian Royal Titulary (Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature, 2013), 160–162; Karola Zibelius-Chen, “Zur Problematik der Lesung des Königsnamens Pi(anch)i,” Der Antike Sudan 17 (2006): 127–133.

- 13. Bowen, “Swearing,” 159.

- 14. Bowen, “Swearing,” 160. Nibley, Approaching, 284 gives the meaning “He [the god] is my life.”

- 15. Nibley, Lehi in the Desert, 28; Nibley, Approaching, 284, 286 (Pakumeni); Book of Mormon Onomasticon, s.v. PACUMENI.

- 16. Nibley, Lehi in the Desert, 23; Book of Mormon Onomasticon, s.v. PACUMENI.

- 17. See, for example, Kumen (3 Nephi 19:4), Kishkumen (Helaman 1:9–12), Kumenonhi (3 Nephi 19:4), and Cumenihah (Mormon 6:14). Because kumen/cumen names show up fairly late in the Book of Mormon onomasticon, well after the Nephites have merged with Mulekites, who had themselves had contact with the Jaredites, some have suspected it may be an element of Jaredite names. No kumen/cumen names show up in the book of Ether, however, so its connection to Jaredite onomastics is uncertain.

- 18. Smith, “Egyptianisms,” 38. Smith also mentions a Hittite city known as Kumani.

- 19. See Book of Mormon Onomasticon, s.v. CUMENI.

- 20. William F. Albright to Grant S. Heward, July 25, 1966, brackets added, parenthesis in the original. A full transcript of this letter is in the possession of BMC staff. Also cited in John A. Tvedtnes, John Gee, and Matthew Roper, “Book of Mormon Names Attested in Ancient Hebrew Inscriptions,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 9, no. 1 (2000): 45.

- 21. Nibley, Lehi in the Desert, 22.

- 22. Nibley, Approaching, 284. See also Nibley, Lehi in the Desert, 23.

- 23. Bowen, “Swearing,” 159–164.