KnoWhy #513 | January 23, 2021

Why Did Mormon and Moroni Write in Reformed Egyptian?

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

“We have written this record according to our knowledge, in the characters which are called among us the reformed Egyptian.” Mormon 9:32

The Know

Having been entrusted with the plates by his father Mormon, the prophet Moroni made a brief remark about the script he and other Nephite record-keepers and prophets had used in composing the record. He said: “And now, behold, we have written this record according to our knowledge, in the characters which are called among us the reformed Egyptian, being handed down and altered by us, according to our manner of speech” (Mormon 9:32, emphasis added). Moroni then went on to say that “if our plates had been sufficiently large we [the Nephite record-keepers] should have written in Hebrew; but the Hebrew hath been altered by us also; and if we could have written in Hebrew, behold, ye would have had no imperfection in our record.” This was punctuated with the comment that “because that none other people knoweth our language, therefore [the Lord] hath prepared means for the interpretation thereof,” meaning the Nephite “interpreters” that Moroni deposited with the plates (Mormon 9:32–34; see also Mosiah 8:13, 19; Alma 37:21; Ether 4:5).

A thousand years before Moroni’s time, Nephi made reference to Egyptian, but in a different sense. At the beginning of 1 Nephi, Nephi said that he was writing his record in “the language of [his] father [Lehi], which consists of the learning of the Jews and the language of the Egyptians” (1 Nephi 1:2, emphasis added). Whatever script Nephi utilized about 550 years before Christ should not be confused with the “reformed Egyptian” spoken of by Moroni.1 The “characters” called “reformed Egyptian” by Moroni were evidently used to record the abridgement of the so-called “large plates” of Nephi (1 Nephi 9)2 and of the Jaredite record on the twenty-four gold plates; that is, the records abridged by Mormon and his son Moroni in the New World in the fourth century AD that included the books of Lehi, Mosiah, Alma, Helaman, 3 Nephi, 4 Nephi, Mormon, Ether, and Moroni. (It also seems likely that Words of Mormon was written in these same characters.)

It is important to note that “Moroni explicitly says that the term reformed Egyptian refers to the script [used to record the Book of Mormon] rather than the language [spoken by the Nephites].”3 Furthermore, Moroni appears to have indicated that the name “reformed Egyptian” was in use specifically among his cohort of Nephite record-keepers. In other words, reformed Egyptian appears to have been a technical scribal term used to specifically describe the type of script being used to engrave the plates of Mormon, not necessarily the name of a broader spoken language or earlier script.4

The Nephites, of course, may have adopted much or part of one or more New World indigenous languages as their spoken day-to-day language not long after they encountered the broader cultural landscape of ancient America.5 In any event, the reformed Egyptian used by Mormon and Moroni in the fourth century AD may have been comparable to several scribal, literary, liturgical, or religious languages that even today are studied and used in certain traditional or academic settings but are not actively used in any day-to-day oral communication, such as Old Church Slavonic, Coptic, Biblical Hebrew, Syriac, Pali, Sanskrit, Avestan, and Latin.6

But why would Mormon and Moroni have not written using a Hebrew script? Moroni explained that “if our plates had been sufficiently large we should have written in Hebrew.” However, their “Hebrew [had] been altered by [them] also.” If he could have written in good Hebrew, Moroni was confident that modern readers “would have [found] no imperfection in [his] record” (Mormon 9:33). Regarding changes in Hebrew script over the centuries, Hebrew indeed developed in form over the first millennium B.C.7 Regarding brevity, Hebrew is an alphabetic script, which means that each word must be spelled out letter by letter (in this case only consonants without vowels) to convey its sound and meaning.8 Egyptian, on the other hand, contains alphabetic (phonograms or sound-signs) as well as logographic (ideograms or sense-signs) characters, meaning characters that can represent a word, phrase, or idea.9

Additionally, Egyptian scripts such as hieratic and especially Demotic can be written in a shortened or abbreviated form.10 This means various forms of Egyptian could conceivably be written more compactly than Hebrew, but at the expense of clarity and accuracy.11 This perhaps explains why Book of Mormon scribes–––concerned with the limited space they had on the plates–––chose Egyptian as their preferred script over Hebrew, despite the difficulty this created for them in writing.12

That Egyptian characters were also “reformed” or “altered” by generations of Nephite scribes “according to [their] manner of speech” is not at all unusual (Mormon 9:32). Languages and scripts inevitably transform over time to accommodate the needs of those speaking, reading, and writing them. This includes ancient Egyptian and, apparently, the form of Egyptian used by the Nephites.13

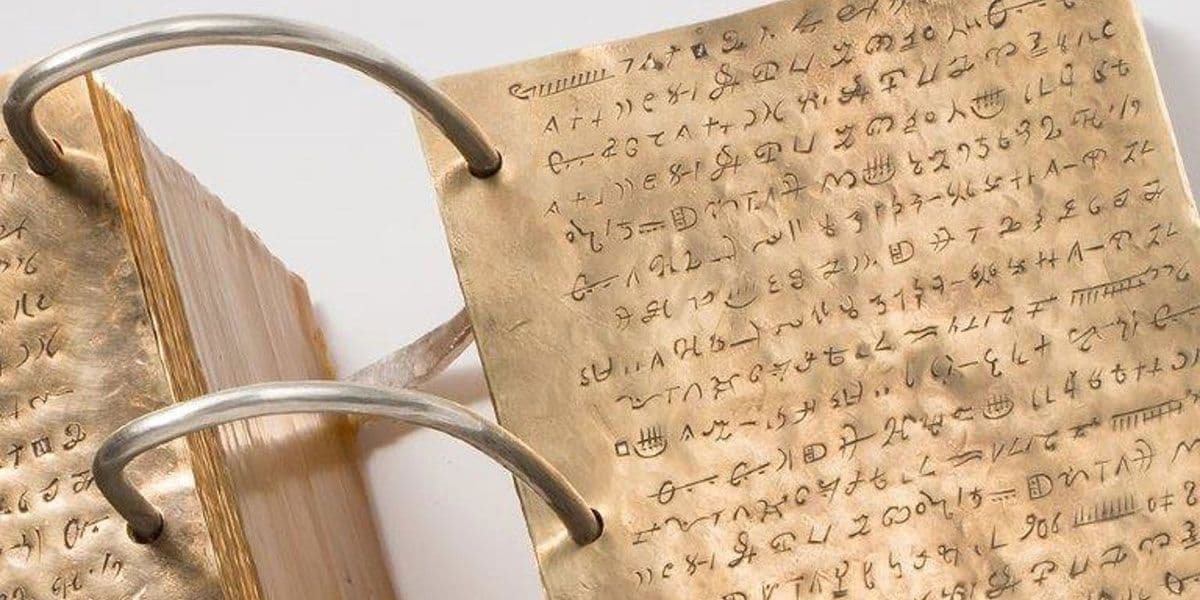

Beyond the handful of characters preserved in the so-called “Anthon Transcript” or “Caractors” Document,14 we may never know what Nephite reformed Egyptian looked like. Without access to the gold plates, we may likewise never know precisely how it functioned as a written script.15 Nevertheless, scholars have recovered ancient Near Eastern texts that perhaps offer comparable examples of “reformed Egyptian.”16

The most enticing of these is the text known today as Papyrus Amherst 63. Discovered on the island of Elephantine in southern Egypt in the late nineteenth century, this papyrus, which post-dates Lehi’s time by about four centuries, “contain[s] three psalms that originated in the Kingdom of Israel before the fall of Samaria (722 BCE).” What makes this text so remarkable is that “the scribes of the scroll used Egyptian Demotic script to write texts in the Aramaic language,” a Semitic language closely related to Hebrew.17 This is comparable to what is depicted in the Book of Mormon: a modified Egyptian script being used to record Israelite texts.18

The Why

The complicating factors described above reveal a number of points. First, these issues help us to understand why Book of Mormon authors would have felt self-conscious about the limitations and failings of their own writing ability. This is especially evident with Moroni, who implored his readers “not [to] condemn [the record] because of the imperfections which are in it” (Mormon 8:12; cf. Mormon 9:31, 33; Ether 12:23–24). The difficulties in writing a lengthy and complex literary-historical work on metal plates in small characters in a highly abbreviated and altered script that likely did not reflect the common language surely made composing the Book of Mormon no easy task for the Nephite prophets, who frankly admitted that “if there are faults [in the record] they are the mistakes of men” (Book of Mormon Title Page).

These difficulties further explain why the Nephite “interpreters” (later called the “Urim and Thummim”) were prepared by the Lord for use in translating the Book of Mormon “by the gift and power of God” in the latter days.19 As Moroni acknowledged, “none other people knoweth our language,” meaning the reformed Egyptian script used to record the history of the Nephites (Mormon 9:34). This was likely a consequence of centuries of linguistic evolution, scribal alterations, and the deliberate destruction of Nephite written sources (Enos 1:13–14; Mormon 6:6).20 Add to this the reality that scholars were just barely beginning to decipher Egyptian in the 1820s when the Book of Mormon came forth, and it at once becomes apparent why special, divinely-prepared instruments were necessary to enable the young and unlearned Joseph Smith to translate the Book of Mormon.21

While several unanswered questions remain about the nature of Nephite reformed Egyptian, there is enough surviving evidence to piece together a believable idea of what it was, how it functioned, and why the Nephite record-keepers chose to utilize it as a script to record the Book of Mormon. Far more important than struggling to scrutinize the unknown (and unknowable) details about reformed Egyptian, however, Moroni encourages and exhorts us as his readers to savor the precious words of Christ preserved in the Book of Mormon by ancient prophets and brought forth to the world by a modern one.

This KnoWhy was made possible by the generous support of the Duane and Marci Shaw Foundation.

Bruce E. Dale, “How Big A Book? Estimating the Total Surface Area of the Book of Mormon Plates,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 25 (2017): 261–268.

William J. Hamblin, “Reformed Egyptian,” FARMS Review 19, no. 1 (2007): 31–35.

Janne M. Sjodahl, “The Book of Mormon Plates,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 10, no. 1 (2001): 22–24, 79.

John Gee, “Epigraphic Considerations on Janne Sjodahl’s Experiment with Nephite Writing,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 10, no. 1 (2001): 25, 79.

John A. Tvedtnes, “Reformed Egyptian,” in The Most Correct Book: Insights from a Book of Mormon Scholar (Salt Lake City, UT; Cornerstone Publishing, 1999), 22–24.

John A. Tvedtnes and Stephen D. Ricks, “Jewish and Other Semitic Texts Written in Egyptian Characters,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 5, no. 2 (1996): 156–163.

John Gee, “Two Notes on Egyptian Script,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 5, no. 1 (1996): 162–176.

Brian D. Stubbs, “Book of Mormon Language,” Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (New York, NY: Macmillan, 1992), 1:179–181.

- 1. On Nephi’s writing in Egyptian, see “Did Ancient Israelites Write in Egyptian?” KnoWhy 4 (January 5, 2016).

- 2. The so-called “large plates” of Nephi are never actually called such by Nephi himself. Rather, Nephi speaks merely of two sets of plates: one containing “a full account of the history of [his] people” that included “an account of the reign of the kings, and the wars and contentions of [Nephi’s] people” and which are called the “large plates” today for their containing an expanded narrative about Nephi, his family, and his descendants (1 Nephi 9:2, 4). These plates were the ones abridged by Mormon in the fourth century AD. Nephi also, however, spoke of “other plates” or “these plates” which he was immediately writing on in 1 Nephi 9 and are called the “small plates” today. These “other plates” or “small plates” were written “for the special purpose that there should be an account engraven of the ministry of my people” (v. 3) and are those which contain the books of 1 Nephi–Omni. See Grant Hardy and Robert E. Parsons, “Book of Mormon Plates and Records,” in Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (New York, NY: Macmillan, 1992), 1:195–201, esp. 199–200.

- 3. John Gee, “Two Notes on Egyptian Script,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 5, no. 1 (1996): 162n1.

- 4. This is consistent with the words in Mosiah 1:2 where Benjamin is said to have caused that his sons were “taught in all the language of his fathers,” and that he himself taught them concerning what was “engraven on the plates of brass,” without saying anything about the characters upon those plates. See William J. Hamblin, “Reformed Egyptian,” FARMS Review 19, no. 1 (2007): 31; John Gee, “La Trahison des Clercs: On the Language and Translation of the Book of Mormon,” Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 6, no. 1 (1994): 79–82, 94–99.

- 5. Brant A. Gardner, Traditions of the Fathers: The Book of Mormon as History (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2015), 151–154, 220–223, 292, 339n41. For differing views, see Brian D. Stubbs, “Book of Mormon Language,” Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (New York, NY: Macmillan, 1992), 1:179–181; John L. Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex: An Ancient American Book (Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship; Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2013), 173–183.

- 6. This, in turn, should alleviate concerns some might have that “reformed Egyptian” is not recognized as a proper linguistic category by modern Egyptologists, since the name was peculiar to the handful of Nephite scribes utilizing it; “they may have been the only people to use that descriptive phrase.” Hamblin, “Reformed Egyptian,” 31–32. In fact, it is not uncommon for the name of a script or language being used by a specific culture or sub-culture to be called something else by outsiders. The ancient Egyptians, for example, did not call their own script “hieroglyphs,” but rather mdw nṯr (“words of god,” “divine words”). The ancient Greeks were the ones who called the script they encountered in Egypt hieroglyphs, meaning “sacred writing.” The same goes for the script that Egyptologists today call Demotic (from Greek meaning “popular” or “of the people”)–––or formerly “Enchorial Egyptian” (from Greek meaning “of the country, rural”)–––but which the ancient Egyptians themselves called sẖȝ šˁ.t (“language of letters”). Likewise, the word “cuneiform” (Latin for “wedge-shaped”) is a modern invention used by scholars to describe the script utilized in ancient Mesopotamia because of the script’s general appearance. None of the ancient cultures that used cuneiform script (including Sumerians, Akkadians, Babylonians, Elamites, Hittites, and Assyrians) ever called it such.

- 7. “North-West Semitics,” “Cursive Script,” and “Square Script” under “Alphabet, Hebrew,” in Encyclopaedia Judaica, ed. Fred Skolnik, 2nd ed. (Farmington Hills, MI: Macmillan Reference; Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House, 2007), 1:689–718.

- 8. Thomas O. Lambdin, Introduction to Biblical Hebrew (New York, NY: Scribner’s, 1971), xxi–xxii.

- 9. Alan Gardiner, Egyptian Grammar, 3rd ed. (Oxford: Griffith Institute, 1957), §6; James E. Hoch, Middle Egyptian Grammar, SSEA Publication XV (Mississauga: Benben Publications, 1997), §4.

- 10. See Hoch, Middle Egyptian Grammar, §3, who describes Demotic as a “much abbreviated” derivation of hieratic script; or Janet H. Johnson, Thus Wrote ˁOnchsheshonqy: An Introductory Grammar of Demotic, 3rd ed. (Chicago, IL: Oriental Institute, 2000), §§3–4, who describes Demotic as “an abbreviated development of hieratic” that is notable for its many “ligatures of two or more” signs; or James P. Allen, Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs, 3rd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), §1.10, who describes Demotic as a “more cursive and abbreviated” script.

- 11. As Egyptologist Joachim Friederich Quack observed, “cursive [Egyptian] writing makes it more difficult to recognize the signs” when reading. Because Demotic is often so abbreviated and cursive, it “is normally considered to be a highly difficult, almost unreadable script. Even within Egyptology, it is a niche for the happy few,” and requires special training to read and translate. Joachim Friederich Quack, “Difficult Hieroglyphs and Unreadable Demotic? How the Ancient Egyptians Dealt with the Complexities of Their Script,” in The Idea of Writing: Play and Complexity, ed. Alex de Voogt and Irving Finkel (Leiden: Brill, 2010), 239, 244.

- 12. See Jacob 3:13; Jacob 4:1–3; Mormon 8:5; Mormon 9:33; Ether 12:23–24. On the physical surface area needed to engrave the Book of Mormon, see Janne M. Sjodahl, “The Book of Mormon Plates,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 10, no. 1 (2001): 22–24, 79; John Gee, “Epigraphic Considerations on Janne Sjodahl’s Experiment with Nephite Writing,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 10, no. 1 (2001): 25, 79; Bruce E. Dale, “How Big A Book? Estimating the Total Surface Area of the Book of Mormon Plates,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 25 (2017): 261–268.

- 13. Gardiner, Egyptian Grammar, §7; Antonio Loprieno, Ancient Egyptian: A Linguistic Introduction (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), §2.4; Hoch, Middle Egyptian Grammar, §§2–3; Johnson, Thus Wrote ˁOnchsheshonqy, §1; Friederich Junge, Late Egyptian Grammar: An Introduction, trans. David Warburton, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Griffith Institute, 2005), §0.2.2; Allen, Middle Egyptian, §§1.8–1.11; The Ancient Egyptian Language: An Historical Study (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), §§1.2–1.4.

- 14. On which, see Stanley B. Kimball, “The Anthon Transcript: People, Primary Sources, and Problems,” BYU Studies 10, no. 3 (1970): 325–352; Michael Hubbard MacKay, Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, and Robin Scott Jensen, “The ‘Caractors’ Document: New Light on an Early Transcription of the Book of Mormon Characters,” Mormon Historical Studies 14, no. 1 (2013): 131–152.

- 15. For varying views, see the sources cited and discussed in John A. Tvedtnes and Stephen D. Ricks, “Jewish and Other Semitic Texts Written in Egyptian Characters,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 5, no. 2 (1996): 156–157n1–3; see also Gee, “La Trahison des Clercs,” 79–82, 94–99.

- 16. See Tvedtnes and Ricks, “Jewish and Other Semitic Texts Written in Egyptian Characters,” 156–163; John A. Tvedtnes, “Reformed Egyptian,” in The Most Correct Book: Insights from a Book of Mormon Scholar (Salt Lake City, UT; Cornerstone Publishing, 1999), 22–24; Hamblin, “Reformed Egyptian,” 32–35.

- 17. Karel van der Toorn, “Three Israelite Psalms in an Ancient Egyptian Papyrus,” The Ancient Near East Today 6, no. 5, May 2018, online at www.asor.org. See further Karel van der Toorn, “Egyptian Papyrus Sheds New Light on Jewish History,” Biblical Archaeology Review 44, no. 4 (July/August 2018): 32–39, 66, 68, online at www.members.bib-arch.org.

- 18. Hamblin, “Reformed Egyptian,” 34.

- 19. On the translation of the Book of Mormon, see “Why Was a Stone Used as an Aid in Translating the Book of Mormon?” KnoWhy 145 (July 18, 2016); “Were Joseph Smith’s Translation Instruments Like the Israelite Urim and Thummim?” KnoWhy 417 (March 20, 2018).

- 20. Interestingly, the late Linda Schele, one of the preeminent Mesoamerican scholars of the last century, observed that there were likely many writing systems in ancient Mesoamerica that have simply not survived. “Stone Slab in Mexico Reveals Ancient Writing System,” New York Times, March 8, 1988, C4. Perhaps “reformed Egyptian” was one such script that did not survive the Nephites and was only preserved in the gold plates.

- 21. The Prophet himself recognized the significance of this. “The fact is that by the power of God I translated the Book of Mormon from hieroglyphics–––the knowledge of which was lost to the world; in which wonderful event I stood alone, an unlearned youth, to combat the worldly wisdom and multiplied ignorance of eighteen centuries.” Joseph Smith to James Arlington Bennet, 13 November 1843, spelling and punctuation standardized, online at www.josephsmithpapers.org. See further “Why Did the Book of Mormon Come Forth as a Miracle?” KnoWhy 273 (February 10, 2017).