KnoWhy #514 | February 19, 2024

Why Did Martin Harris Consult with Scholars like Charles Anthon?

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

“Take these words which are not sealed and deliver them to another, that he may show them unto the learned, saying: Read this, I pray thee. And the learned shall say: Bring hither the book, and I will read them.” 2 Nephi 27:15

The Know

After four years of spiritual preparation with the angel Moroni, Joseph Smith retrieved the golden plates of the Book of Mormon in the early morning hours of September 22, 1827 (Joseph Smith–––History 1:59).1 When he first recovered the plates, Joseph began puzzling over the characters thereon. He apparently couldn’t make sense of them himself. Joseph’s mother Lucy recalled that not long after he received the plates, “Joseph began to make arrangements to accomplish the translation of the record.” The first step, “which he was instructed to take in regard to this matter,” was to make a copy of some of the characters “and send them to some of the most learned men of this generation and ask them for the translation.”2

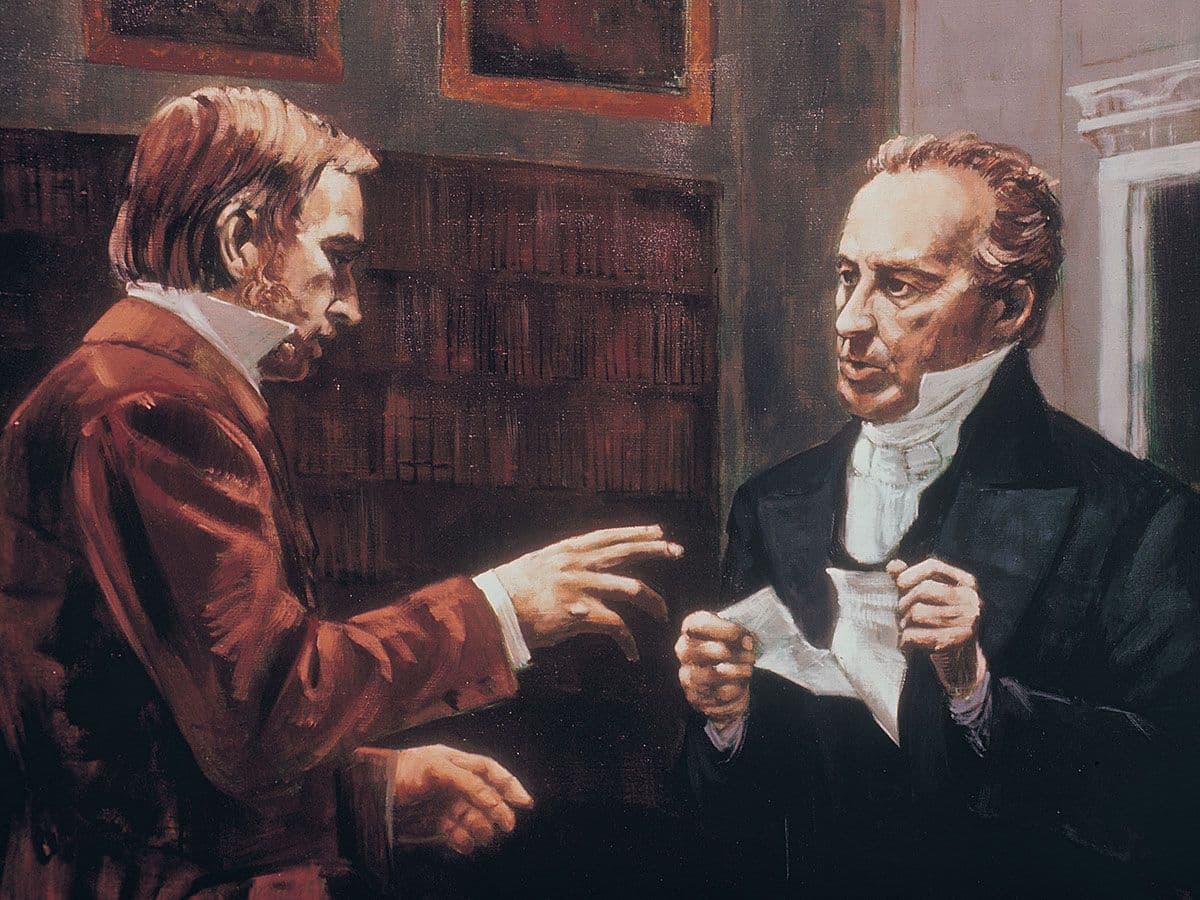

For this reason, Joseph began copying characters from the plates shortly after retrieving them “to find someone other than himself who was able and willing to translate [them].”3 These efforts led to the now-famous incident between Martin Harris and Charles Anthon as recounted in Joseph Smith’s history (JS–History 1:63–65).

But there is more to the story than what is recounted in Joseph Smith’s history canonized today in the Pearl of Great Price. In fact, Martin Harris is known to have consulted with additional scholars besides Charles Anthon. Although Anthon was a pivotal player in this episode, he was not alone.

When Harris was given the transcript of the characters from the Book of Mormon plates prepared by Joseph Smith, he apparently was not instructed “precisely which linguists he was to see,” and so “was left to make those decisions himself.”4 Later sources identify Luther Bradish, “a lawyer, linguist, diplomat, and statesman,” as the first scholar contacted by Harris.5 Bradish, much like Harris himself, was once a prominent citizen of Palmyra, New York (by the time Harris visited him in 1828 he was living in Albany). As a matter of fact, the Harris and Bradish families “were well acquainted with each other, and it is reasonable to conclude that Harris and Luther had crossed paths several times before. In other words, Bradish would have been a friendly first stop for Harris on his trip east and someone who might direct him on who else to see.”6

There is a very understandable reason why Harris would have wanted to show Bradish some of the “reformed Egyptian” characters from the Book of Mormon plates (Mormon 9:32). Bradish had travelled extensively in Egypt and the Middle East between the years 1819–1825. During his travels, Bradish came to know “several key archaeologists . . . who were then excavating and removing all kinds of Egyptian treasures and artifacts. . . . During his stay in the Middle East, Bradish had also become conversant with several of the native languages in the region, at least well enough to get by, and had become familiar with Egyptian hieroglyphs.”7

The details of Harris’s visit with Bradish are unfortunately not known. In any case, after visiting with Bradish, Harris then met with the scholar Samuel L. Mitchill.8 A learned and well-respected naturalist, Mitchill had taken an interest in “anthropological and linguistic studies of local Indian tribes”9 in New York state, with “Indian hieroglyphics and illustrations of Indian mounds . . . [being] subjected to his critical knowledge for opinion.”10 It is likely that Harris consulted with Mitchill precisely because Joseph Smith had been led to uncover an ancient record “giving an account of the former inhabitants of this continent and the source from whence they sprang.”11

Mitchill would have taken extreme interest to just such a record. According to one contemporary source, during Harris’s consultation Mitchill “compared [the characters] with the hieroglyphics discovered by Champollion in Egypt—and set them down as the language of a people formerly in existence in the east but now no more.”12

Mitchill, in turn, recommended that Harris visit Charles Anthon, a professor at Columbia College in New York City. A brilliant classicist fluent in Greek, Latin, German, and French, Anthon received Harris and agreed to examine the transcript of characters prepared by Joseph Smith. Exactly what Anthon said after his examination is difficult to know, since Harris and Anthon left contradictory accounts of the incident. Harris, of course, remembered Anthon pronouncing the characters genuine but then quickly dismissing the affair by protesting “I cannot read a sealed book” when informed that the source of the characters (the gold plates) was not available for scholarly examination because “an Angel of God” had revealed it.13

Anthon, on the other hand, repeatedly denied ever endorsing the authenticity of the characters and claimed to have warned Harris that he was being taken in by a con job.14 A plausible scenario that could account for this conflicting testimony is that Anthon initially believed the characters could be authentic and expressed interested in them but quickly backed away after the Book of Mormon was printed and his name became associated with a national religious scandal.15

One thing, however, is very clear. “Whatever Harris gleaned from these leading scholars, if he left Palmyra wondering and inquiring, he returned home supporting and defending the translation of the Book of Mormon.”16 Not only that, he and Joseph Smith saw Anthon’s now-famous declaration (“I cannot read a sealed book”) as fulfillment of the prophecy in Isaiah 29:11–14. As Joseph Smith narrated in his 1832 history,

We proceeded to copy some of [the characters], and he [Martin Harris] took his journey to the eastern cities and to the learned, saying, “Read this, I pray thee.” And the learned said, “I cannot. But if he would bring the plates, [I] would read it.” But the Lord had forbid it and he returned to me and gave them to me to translate. And I said, “I cannot for I am not learned.” But the Lord had prepared spectacles to read the book. Therefore, I commenced translating the characters and thus the prophecy of Isaiah was fulfilled.17

The Why

In a letter to W. W. Phelps, Oliver Cowdery indicated that on the first night of his appearance on September 21, 1823, the angel Moroni informed Joseph Smith that the prophecy in Isaiah 29:11–14 needed to be fulfilled before the Book of Mormon could be translated, “for thus has God determined to leave men without excuse.”18 Early members of the restored Church of Jesus Christ thus came to understand Martin Harris’s consultation with scholars, particularly Charles Anthon, as having portentous significance for the work of the Restoration in the latter days.19

Whatever he may have come to think about the Book of Mormon, Anthon (perhaps unwittingly) helped fulfill the prophecy in Isaiah 29. His dismissive response to Harris may have been an attempt at being clever, but his words would come to inspire Harris and later millions of believers around the world to accept the authenticity of the Book of Mormon.

Besides this, Harris’s consultation with scholars, on the behest of Joseph Smith, reveals the Prophet’s learning process. His ability to translate the Book of Mormon ultimately came by the gift and power of God, but Joseph nevertheless employed “secular” means to aid his efforts. “Though generations of Mormons saw the outcome of Harris’s trip to New York City to be the fulfillment of prophecy and a catalyst for Joseph Smith’s miraculous translation,” observes historian Michael MacKay, “the impetus for the trip was of a secular nature. . . . [T]he characters on the plates were not just the object of Joseph’s miraculous translation; some of the foremost scholars in ancient languages [at the time] examined the[m].”20

Joseph followed this pattern throughout his ministry as he studied biblical languages and the Egyptian papyri associated with the translation of the Book of Abraham.21 Revelation directs us to follow the Prophet’s example by utilizing the tools of scholarship as we seek to uncover and understand divine truth (D&C 88:118). As President Russell M. Nelson taught, “Good inspiration is based upon good information.”22

Through this process Joseph gained confidence and learned to proceed independently. The characters Joseph prepared for Martin Harris were shown to some of the most learned men of their day and yet none of them could do much more than offer speculation about their antiquity and nature. This showed Joseph that he could not rely solely on the word of scholarly consensus.23 Since secular knowledge is always developing with new discoveries and the articulation of new theoretical paradigms, scholarship will always have its limits. As Nephi taught centuries ago, “To be learned is good if [one] hearken[s] unto the counsels of God” (2 Nephi 9:29).

The consultation with scholars also served to assure Martin Harris. Although the reactions of these learned men varied, Harris was satisfied enough with their replies to further assist with the translation and publication of the Book of Mormon. He served as scribe, financier, and witness of the Book of Mormon, all at great personal sacrifice.24

Besides shouldering the financial burden of printing the Book of Mormon, from which he never fully recovered, Martin’s once-sterling reputation suffered as a result of his undeviating faith in Joseph Smith after his trip to Mitchill and Anthon in New York City. His family and friends were “generally repulsed by his enthusiasm for a young man whose purported visions upset the greater Palmyra community. Friends advised him to cease espousing Joseph’s schemes. When Martin refused, they pronounced him deceived, if not deranged. . .. Yet he continued to side with Joseph Smith and risk further harm to his now spoiled reputation,”25 all the while knowing in his heart and in his mind the truthfulness of the work he was engaged in.

This KnoWhy was made possible by the generous contribution of Thomas W. Sederberg

Susan Easton Black and Larry C. Porter, Martin Harris: Uncompromising Witness of the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 2018), 88–101.

Richard E. Bennett, “Martin Harris’s 1828 Visit to Luther Bradish, Charles Anthon, and Samuel Mitchill,” in The Coming Forth of the Book of Mormon: A Marvelous Work and a Wonder, ed. Dennis L. Largey et al. (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2015), 103–115.

Richard E. Bennett, “‘A Very Particular Friend’—Luther Bradish,” in Approaching Antiquity: Joseph Smith and the Ancient World, edited by Lincoln H. Blumell, Matthew J. Grey, and Andrew H. Hedges (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 63–82.

Michael Hubbard MacKay, “‘Git Them Translated’: Translating the Characters on the Gold Plates,” in Approaching Antiquity: Joseph Smith and the Ancient World, edited by Lincoln H. Blumell, Matthew J. Grey, and Andrew H. Hedges (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 83–116.

Richard E. Bennett, “‘Read This I Pray Thee’: Martin Harris and the Three Wise Men of the East,” Journal of Mormon History 36, no. 1 (Winter 2010): 178–216.

- 1. Richard E. Bennett, School of the Prophet: Joseph Smith Learns the First Principles, 1820–1830 (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2010); Michael Hubbard MacKay and Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, From Darkness unto Light: Joseph Smith’s Translation and Publication of the Book of Mormon (Provo and Salt Lake City, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University and Deseret Book, 2015); Saints: The Story of the Church of Jesus Christ in the Latter Days, Volume 1, The Standard of Truth, 1815–1846 (Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2018), 20–42. For Emma’s role in helping Joseph retrieve the plates, see Book of Mormon Central, “How Did Emma Smith Help Bring Forth the Book of Mormon? (2 Nephi 27:6),” KnoWhy 386 (November 30, 2017).

- 2. Lucy Mack Smith, History, 1845, p. 117, online at www.josephsmithpapers.org, spelling and punctuation standardized. Other sources similarly recount that Joseph initially looked to others to help in the translation. Joseph Knight Sr., an early believer, remembered: “[Joseph Smith] now began to be anxious to get them translated. He therefore, with his wife, drew off the characters exactly like the ancient [ones] and sent Martin Harris to see if he could get them translated.” Reproduced in Dean C. Jessee, “Joseph Knight’s Recollection of Early Mormon History,” BYU Studies 17, no. 1 (Autumn 1976): 34, spelling and punctuation standardized. An early skeptical source who likely got his information from Joseph Smith or someone close to the translation of the Book of Mormon likewise reported: “So blindly enthusiastic was Harris, that he took some of the characters interpreted by Smith, and went in search of some one besides the interpreter, who was learned enough to English them.” Jonathan Hadley, “Golden Bible,” Palmyra Freeman (Palmyra, New York) (August 11, 1829), emphasis in original; reprinted in Larry E. Morris, ed., A Documentary History of the Book of Mormon (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2019), 238.

- 3. Michael Hubbard MacKay, “‘Git Them Translated’: Translating the Characters on the Gold Plates,” in Approaching Antiquity: Joseph Smith and the Ancient World, ed. Lincoln H. Blumell, Matthew J. Grey, and Andrew H. Hedges (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2015), 83.

- 4. Richard E. Bennett, “‘A Very Particular Friend’—Luther Bradish,” in Approaching Antiquity: Joseph Smith and the Ancient World, edited by Lincoln H. Blumell, Matthew J. Grey, and Andrew H. Hedges (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 66.

- 5. Bennett, “‘A Very Particular Friend’,” 66; Susan Easton Black and Larry C. Porter, Martin Harris: Uncompromising Witness of the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 2018), 91–92.

- 6. Bennett, “‘A Very Particular Friend’,” 67–68.

- 7. Bennett, “‘A Very Particular Friend’,” 69; “‘Read This I Pray Thee’: Martin Harris and the Three Wise Men of the East,” Journal of Mormon History 36, no. 1 (Winter 2010): 184–189.

- 8. Bennett notes that “some question remains as to whether Harris met with Mitchill first or with Charles Anthon first,” since the historical sources are not entirely clear on the sequence of the visits. The combined evidence appears to portray Harris as meeting with Mitchill first, then Anthon. Bennett, “‘A Very Particular Friend’,” 72–73.

- 9. Bennett, “‘A Very Particular Friend’,” 71; Richard E. Bennett, “‘A Nation Now Extinct,’ American Indian Origin Theories as of 1820: Samuel L. Mitchill, Martin Harris, and the New York Theory,” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 20, no. 2 (2011): 30–51.

- 10. John W. Francis, Reminiscences of Samuel Latham Mitchill, M.D., LL.D. (New York, NY: John F. Trow, 1859), 17, quoted in Black and Porter, Martin Harris, 97–98.

- 11. History, 1838–1856, volume A-1 [23 December 1805–30 August 1834], 5, online at www.josephsmithpapers.org.

- 12. James Gordon Bennett, “Mormon Religion—Clerical Ambition—Western New York—the Mormonites Gone to Ohio,” Morning Courier and Enquirer, September 1, 1831, reprinted in Leonard J. Arrington, “James Gordon Bennett’s 1831 Report on ‘The Mormonites’,” BYU Studies 10, no. 3 (1970): 362.

- 13. History, 1838–1856, volume A-1 [23 December 1805–30 August 1834], 9, online at www.josephsmithpapers.org.

- 14. Charles Anthon to E. D. Howe, 17 February 1834, in E. D. Howe, Mormonism Unvailed (Painesville, OH: E. D. Howe, 1834), 270–272; Charles Anthon to Thomas Winthrop Coit, 3 April 1841; Charles Anthon to William E. Vibbert, 12 August 1844. Transcriptions of and commentary on these sources can be accessed in Morris, A Documentary History of the Book of Mormon, 229–236.

- 15. “Anthon’s . . . . accounts have a marked flavor of self-justification, of putting himself in the best light.” Bennett, “‘Read This I Pray Thee’,” 195.

- 16. Richard E. Bennett, “Martin Harris’s 1828 Visit to Luther Bradish, Charles Anthon, and Samuel Mitchill,” in The Coming Forth of the Book of Mormon: A Marvelous Work and a Wonder, ed. Dennis L. Largey et al. (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2015), 105. This fact raises questions about the truthfulness of Anthon’s denials of ever affirming that the characters shown to him were authentic. “Although Dr. Anthon consistently downplayed Martin’s interpretation of the interview(s) with himself in these letters, it is noted that Harris’s confidence in the veracity of gold plates grew dramatically during the exchange between the two men. If Anthon’s recollection of their visit is accurate, Martin likely would have been less inclined to pursue his relationship with Joseph Smith.” Black and Porter, Martin Harris, 97.

- 17. History, circa Summer 1832, 5, online at www.josephsmithpapers.org, spelling, punctuation, and grammar standardized.

- 18. Oliver Cowdery, “Letter IV,” The Latter Day Saints’ Messenger and Advocate 1, no. 5 (February 1835): 80.

- 19. MacKay, “‘Git Them Translated’,” 101–102.

- 20. MacKay, “‘Git Them Translated’,” 103–104.

- 21. On such, see generally Matthew J. Grey, “‘The Word of the Lord in the Original’: Joseph Smith's Study of Hebrew in Kirtland,” in Approaching Antiquity, 249–302; John W. Welch, “Joseph Smith’s Awareness of Greek and Latin,” in Approaching Antiquity, 303–28; Kerry Muhlestein, “Joseph Smith and Egyptian Artifacts: A Model for Evaluating the Prophetic Nature of the Prophet’s Ideas about the Ancient World,” BYU Studies Quarterly 55, no. 3 (2016): 35–82; Robin Scott Jensen and Brian M. Hauglid, “Volume 4 Introduction: Book of Abraham and Related Manuscripts,” in The Joseph Smith Papers, Revelations and Translations, Volume 4: Book of Abraham and Related Manuscripts (Salt Lake City, UT: Church Historians Press, 2018), xiii–xxix, online at www.josephsmithpapers.org.

- 22. Russell M. Nelson, “Revelation for the Church, Revelation for Our Lives,” April 2018 General Conference, online at lds.org.

- 23. “The fact is that by the power of God I translated the Book of Mormon from hieroglyphics–––the knowledge of which was lost to the world; in which wonderful event I stood alone, an unlearned youth, to combat the worldly wisdom and multiplied ignorance of eighteen centuries.” Joseph Smith to James Arlington Bennet, 13 November 1843, spelling and punctuation standardized, online at www.josephsmithpapers.org.

- 24. See Book of Mormon Central, “How Did Martin Harris Help Bring Forth the Book of Mormon?” KnoWhy 291 (March 24, 2017).

- 25. Black and Porter, Martin Harris, 101.