KnoWhy #774 | January 23, 2025

Why Did Charles Anthon Compare the Characters He Was Shown to Many Languages?

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

“Professor Anthon stated that the translation was correct, more so than any he had before seen translated from the Egyptian. I then showed him those which were not yet translated, and he said that they were Egyptian, Chaldaic, Assyriac, and Arabic; and he said they were true characters.” Joseph Smith—History 1:64

The Know

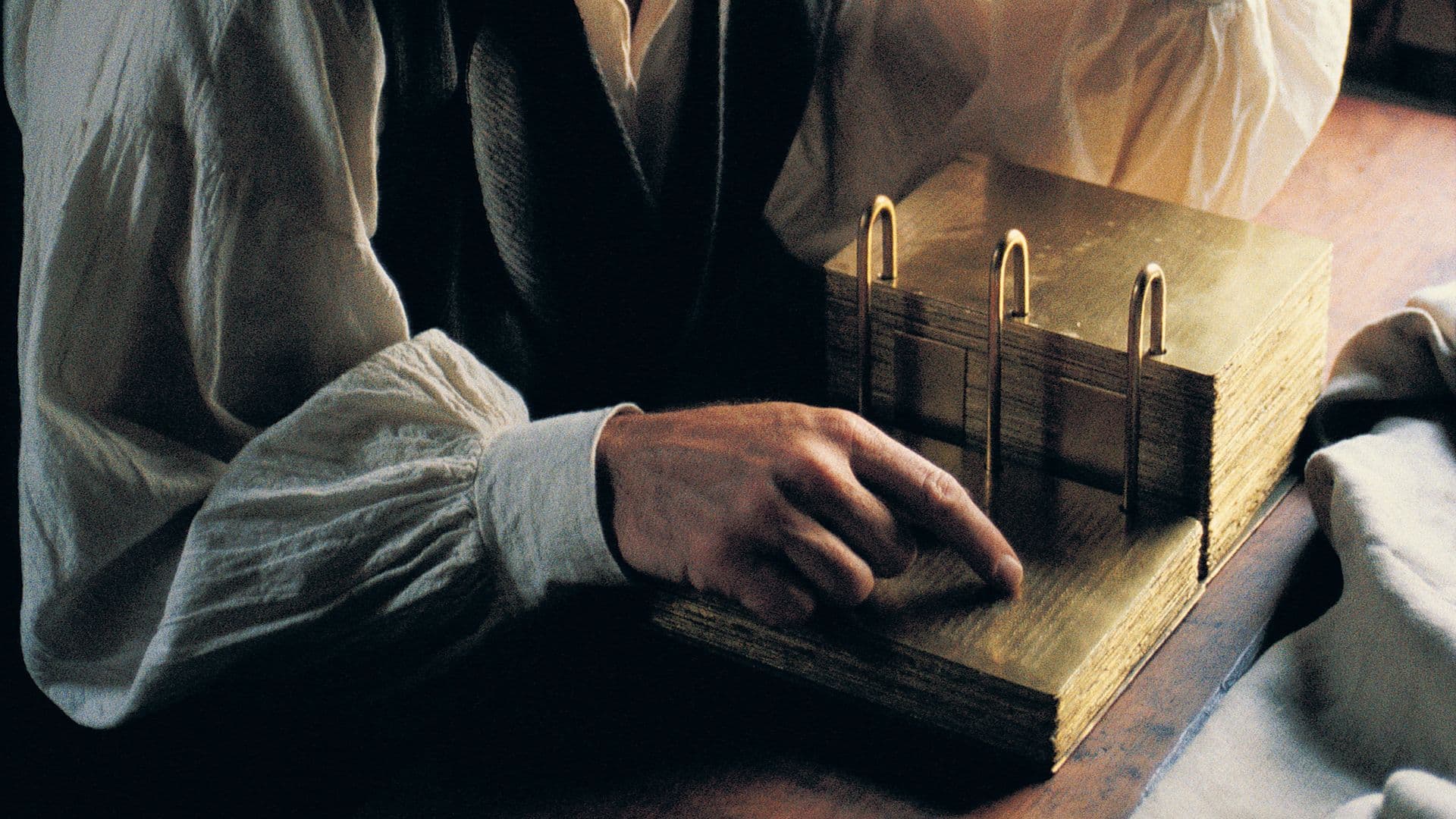

During the winter of 1828, Martin Harris traveled to New York City with a set of characters that Joseph Smith had copied from the gold plates received from the angel Moroni. After initially meeting with Luthar Bradish in Albany and Dr. Samuel L. Mitchill, Martin was referred to Professor Charles Anthon of Columbia University.1 According to Martin Harris’s account, after Anthon saw the characters from the plates, he pronounced some to be correctly translated “from the Egyptian” and other untranslated characters to be “Egyptian, Chaldaic, Assyriac, and Arabic; and he said they were true characters” (Joseph Smith—History 1:64).

Based on these statements, John S. Thompson has proposed that Martin showed two sets of characters to Anthon: “a script Anthon simply identified as Egyptian and another script containing characters of a less certain origin.”2 The first, clearly identified as Egyptian, would be from the small plates of Nephi, while the second, which Anthon had a harder time identifying, contained “the characters which are called among us the reformed Egyptian” that Mormon and Moroni used a thousand years later (Mormon 9:32).

“Since Nephi and Jacob lived around a thousand years before Mormon and Moroni,” Thompson notes, “the language and characters on this small record would not have been the altered ‘reformed Egyptian’ that Mormon and Moroni used. Rather, Nephi tells his readers plainly that he wrote using ‘the language of the Egyptians’ (1 Nephi 1:2), a language that his father Lehi knew how to read and had taught to his children (Mosiah 1:4).”3 As such, characters from across the plates could have been sampled and copied for the manuscript Martin took to Anthon.4

One indication that Anthon did identify some characters as actual Egyptian comes from W. W. Phelps. When Phelps was investigating the Church, he wrote a letter that contains information likely given to him from Martin Harris himself. In this letter, Phelps stated that Anthon “declared [the characters] to be ancient short-hand Egyptian.”5 This phrase likely reflected something that a scholar had actually told Martin. In Anthon’s Classical Dictionary, he cited various works that described hieratic Egyptian as a tachygraphy, or shorthand, of Egyptian hieroglyphs. Anthon himself described hieratic as “running imitations or abridgments of the corresponding hieroglyphics.”6 Oliver Cowdery also later compared the Book of Mormon characters to the hieratic characters on the Egyptian papyri that Joseph bought from Michael Chandler, which could also indicate that some form of hieratic appeared on the plates.7

Manuscript | Book of Mormon source | Anthon’s interpretation |

Transcript 1 | Small plates, “the language of the Egyptians” (1 Nephi 1:2) | Egyptian |

Transcript 2 | Large plates; “reformed Egyptian” (Mormon 9:32) | Egyptian, Assyriac, Chaldaic, Arabic |

While this would explain how Anthon was able to identify some characters alongside their translation, he was not able to identify them all and apparently compared them to “Egyptian, Chaldaic, Assyriac, and Arabic.” This list of seemingly unrelated languages may initially seem odd to readers of the Book of Mormon. It is unlikely, however, that Joseph Smith or his associates were aware of what language the plates were written in prior to Martin’s visit with Anthon, since as Michael Hubbard MacKay and Gerrit J. Drikmaat have observed, “the angel Moroni . . . apparently did not explain to Joseph that the record was written in reformed Egyptian. None of the records describing Moroni’s visit claim that he told Joseph about the language.”8

In the record itself, Moroni also informs readers that “none other people knoweth our language,” which likely contributed to Anthon’s apparent confusion (Mormon 9:34). According to Thompson, this suggests that “even an ancient Egyptian would not have understood their language in spite of the name given.”9 As such, we should expect that scholars such as Anthon would naturally have had a difficult time trying to determine the origin of the scripts shown to him, especially at a time when Egyptology was still developing as a field of study.10 Furthermore, while the languages on his list may initially appear unrelated, Anthon’s assessment may actually make sense for several reasons when considered in its full context.

First, Anthon reportedly listed Chaldaic as one of the languages represented by the characters. The name Chaldaic (alternatively known as Chaldean) in the 1820s referred not to Babylonian Cuneiform as some might assume but rather to what is now known by scholars as Aramaic.11 Following the Babylonian captivity, the Aramaic script was also used to write Hebrew. This designation, then, could also shed light on other statements regarding Harris’s visit with Anthon.

William Smith, for instance, later recollected what he had heard about this meeting, presumably from his brother Joseph or Martin himself. In William’s retelling, Anthon “pronounced the characters to be ancient Hebrew corrupted, and the language to be degenerate Hebrew with a mixture of Egyptian.”12 Interestingly, even in his denials Anthon did grant that some of the characters looked like “rude imitations of Hebrew,” or Hebrew letters “more or less distorted.”13 This Hebrew element was likely the Chaldaic/Aramaic script referred to by Martin.14

Moreover, the Assyriac Harris referenced would not likely have been the language of ancient Assyria (Akkadian was not deciphered until the mid-nineteenth century). It seems more likely that Anthon referred to Syriac, a language related to Aramaic that began to be used by early Christians around the first century AD. This possibility is further strengthened by a reported interview with Martin in which he described the four languages as “Arabic, Chaldaic, Syriac, and Egyptian.”15

While Syriac, a script developed well after Nephi left Jerusalem, was certainly not on the plates, scholars of the nineteenth century with whom Anthon was familiar did compare both Syriac and Arabic to a form of demotic Egyptian. One work Anthon cited in his own Classical Dictionary, for example, stated that examples of demotic differed significantly from the hieroglyphic form and were closer to “the old Arabic or Syriac characters to which they bear, at first sight, a considerable resemblance.”16

A surviving copy of the Book of Mormon script known as the “Caractors document” has sometimes been mistaken for the transcript shown to Anthon. It was actually copied by John Whitmer at some unknown time later but may reflect some of the characters shown to Anthon in 1828.17 Interestingly, two twentieth-century Egyptologists, William Hayes and Richard A. Parker, independently analyzed this document and believed the script could be derived from some form of demotic or hieratic.18 In addition, Hugh Nibley saw a striking resemblance between the “Caractors document” and meroitic cursive—“a script adapted (or ‘reformed’) from demotic to write the non-Egyptian language spoken anciently in Sudan.”19

The Why

Ultimately, the mention of these four languages together would have been an odd detail for two New York farmers, Joseph Smith and Martin Harris, to come up with on their own. This would have especially been odd since the Book of Mormon itself only mentions one of these languages. Other details, such as the text being written in “shorthand Egyptian,” would also be hard for Smith and Harris to come up with on their own.

In contrast, none of these details would be at all odd or out of place for an academic such as Charles Anthon, who was immersed in the scholarship of his time. If Martin Harris had shown him characters copied from a reformed Egyptian script, it would not be surprising to see Anthon struggle to determine the exact provenance of the script and lay out a few possibilities of alphabets that resembled what he saw. Indeed, the presence of Syriac (Assyriac) alongside Arabic and Egyptian would demonstrate the difficulty Anthon faced committing to a language. This could have also motivated his subsequent desire to see the source document himself, as Martin Harris asserted.

Neal Rappleye observed, “The languages Martin remembers Anthon . . . mentioning suggest that someone with an academic background in ancient languages did see a resemblance to both Hebrew and Egyptian (demotic and hieratic) scripts.”20 This detail lines up with the Book of Mormon’s own claims to be written in a reformed Egyptian, possibly with some reformed Hebrew influence.

All of this suggests that Joseph Smith copied characters from a real, ancient source. He was then able to translate that source, written in an unknown language, by the gift and power of God and publish it as the Book of Mormon.

Neal Rappleye, “‘Written upon Gold Plates’: Comparing Witness Descriptions with Artifacts from the Pre-Modern World,” unpublished manuscript.

John S. Thompson, “Looking Again at the Anthon Transcript(s),” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 63 (2025): 353–366.

Scripture Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: The Anthon Account,” Evidence 219 (July 1, 2021).

- 1. For more on Martin’s visit with these scholars, see Richard E. Bennett, “Martin Harris’s 1828 Visit to Luther Bradish, Charles Anthon, and Samuel Mitchill,” in The Coming Forth of the Book of Mormon: A Marvelous Work and a Wonder, ed. Dennis L. Largey, Andrew H. Hedges, John Hilton III, and Kerry Hull (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Deseret Book, 2015), 103–115; Michael Hubbard MacKay, “‘Git Them Translated’: Translating the Characters on the Gold Plates,” in Approaching Antiquity: Joseph Smith and the Ancient World, ed. Lincoln H. Blumell, Matthew J. Grey, and Andrew H. Hedges (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Deseret Book, 2015), 83–116; Michael Hubbard MacKay and Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, From Darkness unto Light: Joseph Smith’s Translation and Publication of the Book of Mormon (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Deseret Book, 2015), 39–60.

- 2. John S. Thompson, “Looking Again at the Anthon Transcript(s),” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 63 (2025): 358.

- 3. Thompson, “Looking Again at the Anthon Transcript(s),” 359.

- 4. It is important to remember that Joseph likely translated the small plates last and that any Egyptian character from the small plates that would have been translated correctly (in Anthon’s estimate) need not be a long running text. Thus, Thompson, “Looking Again at the Anthon Transcript(s),” 363 notes, “The Anthon episode does not appear to deal with any translation of words or sentences. . . . Anthon was not in a position to do so, but he likely had a simple understanding of a few Egyptian characters. Since the 1838 History reports that Joseph Smith only sent with Harris a translation of ‘some’ characters, any assumption that he translated words or sentences at this point goes beyond the text.”

- 5. W. W. Phelps to E. D. Howe, January 15, 1831, in E. D. Howe, Mormonism Unvailed [sic] (Painesville, OH, 1834), 273.

- 6. Charles Anthon, A Classical Dictionary (New York, NY, 1841), 45; emphasis added. For instances of hieratic being described as shorthand Egyptian in works referred to by Anthon that predate Martin’s visit, see Jean-Francois Champollion, Precis du systeme hieroglyphique des anciens Egyptiens, 2 vols (Paris, 1824), 1:18, 20, 354–355; James Browne, “Hieroglyphics,” Edinburgh Review 45, no. 89 (1826): 145.

- 7. Oliver Cowdery to William Fry, published in Latter Day Saints' Messenger and Advocate 2, no. 3 (December 1835): 234–235; as discussed in Thompson, “Looking Again at the Anthon Transcript(s),” 362–363.

- 8. MacKay and Dirkmaat, From Darkness unto Light, 42.

- 9. Thompson, “Looking Again at the Anthon Transcript(s),” 358. Mormon 9:33 also refers to a Hebrew script the Nephites used, but it was not used to write the Book of Mormon and had also been altered over the Nephites’ thousand-year history.

- 10. MacKay and Dirkmaat, From Darkness unto Light, 44, note that it was not until 1822— just a few years prior to Harris’s visit with Anthon—that steps were taken for scholars to be able to finally decipher the Egyptian language.

- 11. John Gee and Stephen D. Ricks, “Historical Plausibility: The Historicity of the Book of Abraham as a Case Study,” in Historicity and the Latter-Day Saint Scriptures, ed. Paul Y. Hoskisson (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2001), 72. See Oxford English Dictionary, “Chaldaic” and “Chaldee.”

- 12. James Murdock to Congregational Observer, June 19, 1841, “The Mormons and Their Prophet,” Congregational Observer 2 (July 3, 1841), in Dan Vogel, ed., Early Mormon Documents, 5 vols. (Signature Books, 1996),1:479.

- 13. Charles Anthon to William E. Vibbert, August 12, 1844, in “A Fact in the Mormon Imposture,” New York Observer 23, no. 69 (May 3, 1845), in Larry E. Morris, ed., A Documentary History of the Book of Mormon (Oxford University Press, 2019), 235; Charles Anthon to Rev. T. W. Coit, April 3, 1841, in Morris, Documentary History, 232. It is worth noting that in these letters, however, Anthon did claim these characters were mixed with similarly distorted Greek rather than Egyptian.

- 14. Because the Nephites had a reformed Hebrew script as well, it is possible that some elements of their Hebrew would have influenced their reformed Egyptian script and therefore been included on the plates. Stephen D. Ricks and John A. Tvedtnes, “Jewish and Other Semitic Texts Written in Egyptian Characters,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 5, no. 2 (1996): 156–163, have also noted that some Old World Israelite texts utilized Hebrew and Egyptian scripts. While this would have evolved from the proto-Hebrew rather than the Aramaic script, it nonetheless provides an interesting possibility as to the presence of the apparent Hebrew- or Aramaic-like characters Anthon recognized.

- 15. Joel Tiffany, “Mormonism—No. 2,” Tiffany’s Monthly 5, no. 4 (August 1859): 162, in Morris, Documentary History, 192; emphasis added.

- 16. “Egypt,” Supplement to the Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Editions of the Encyclopaedia Britannica (Edinburgh, 1824), 54. The apparent similarities between Arabic and cursive demotic may explain why Joseph Smith Sr., Hyrum Smith, and William McLellin also stated that the plates contained Arabic characters. See Rappleye, “‘Written Upon Gold Plates’: Comparing Witness Descriptions with Artifacts from the Pre-Modern World,” unpublished manuscript.

- 17. For more information regarding this manuscript, see Scripture Central, “What Do We Know About the ‘Anthon Transcript’? (Mosiah 8:12),” KnoWhy 515 (May 9, 2019). We ultimately do not know what the original manuscript Martin showed to Anthon looked like. It is possible that multiple transcripts were shown to Anthon, some translated and some untranslated. For more on this possibility, see Thompson, ““Looking Again at the Anthon Transcript(s),” 353–366.

- 18. While most of the relatively few scholars who have considered the issue have been dismissive of the Anthon transcript, two Egyptologists suggested a resemblance to Egyptian scripts. William Hayes, former curator of Egyptian art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, thought it could conceivably have been an example of hieratic script. William C. Hayes to Paul M. Hanson, June 8, 1956, published in Paul M. Hanson, “The Transcript from the Plates of the Book of Mormon,” Saints Herald 103 (November 12, 1956): 1098. Richard A. Parker of the Department of Egyptology at Brown University thought the characters “could well be the latest form of the written language – demotic characters.” Richard Parker to Marvin W. Cowan, March 22, 1966; see also Richard Bushman to Marvin S. Hill, March 30, 1985, cited in Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS) Staff, Martin Harris's Visit with Charles Anthon: Collected Documents on the Anthon Transcript and “Shorthand Egyptian,” FARMS Reports (FARMS, 1990), 7n27.

- 19. Hugh Nibley, Since Cumorah, 2nd ed. (Deseret Book; FARMS, 1988), 149–150; Hugh Nibley, The Prophetic Book of Mormon (Deseret Book; FARMS, 1989), 386–387.

- 20. Rappleye, “‘Written upon Gold Plates.’”