KnoWhy #471 | January 13, 2024

Why Can Nephi’s Vision Be Called an Apocalypse?

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

"And the Spirit said unto me: Behold, what desirest thou? And I said: I desire to behold the things which my father saw." 1 Nephi 11:2-3

The Know

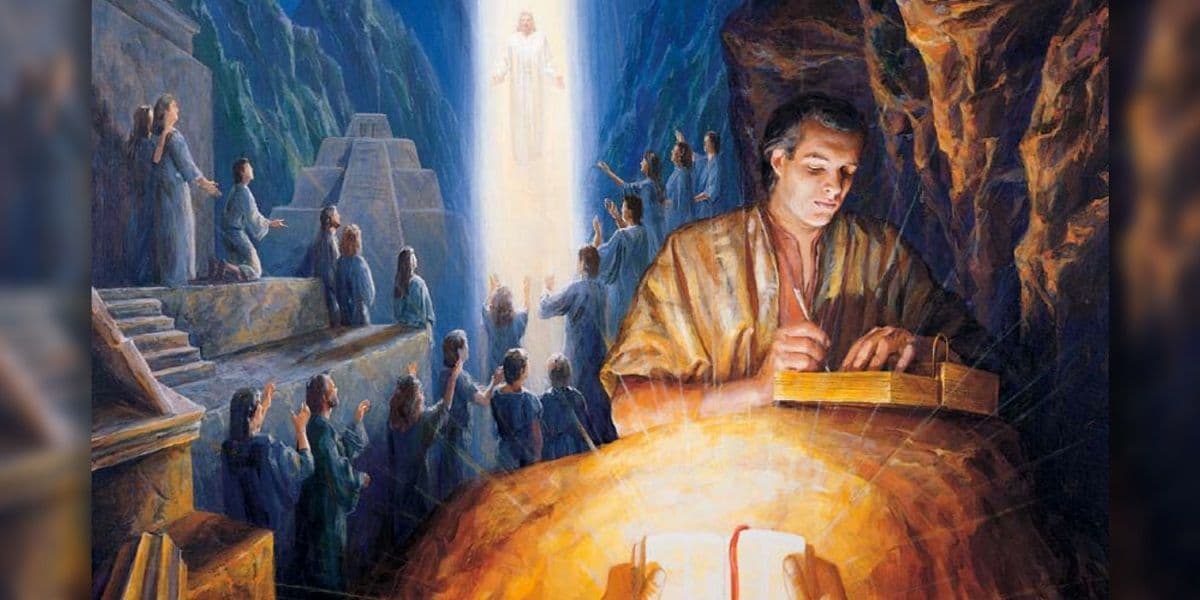

In 1 Nephi 11–14, Nephi had a vision in which heavenly messengers showed him various things that would happen in the future. They also explained to him the symbolic vision of his father. Nephi’s vision is similar in many ways to known apocalyptic texts, such as the Book of Daniel and the Book of Enoch.1 It is even more similar to texts in the Old Testament, like Zechariah, that are generally considered to be the forerunners of fully developed apocalyptic literature.2 Yet because those texts were written well after Lehi and Nephi left Jerusalem, one might wonder how a vision, like the ones found in 1 Nephi, could turn up in the sixth century BC. New evidence from an Assyrian text provides a possible explanation for the apocalyptic nature of Nephi’s vision.

A text called The Underworld Vision of an Assyrian Prince, written in the Akkadian language, depicts a visionary named Kummay, who was shown a vision of the underworld.3 According to Richard J. Clifford, a scholar of apocalypticism, this text is of interest “as a precedent for the tours of heaven and hell that are popular in later … apocalypses.”4 This text is especially interesting for Book of Mormon studies because it dates from the early seventh-century BC, shortly before the time of Lehi.

This text is similar to 1 Nephi 11–14. In it, the Assyrian prince Kummay experienced an expansive vision.5 In a similar way Nephi, who would eventually become king, experienced a significant vision. Such elevating experiences typically validated royal prerogatives.

The Assyrian prince asked to receive the vision, and consequently the gods granted his desire.6 Nephi likewise asked the Spirit of the Lord if he could see what his father had seen, and was granted a vision based on this request (1 Nephi 11:3).

Kummay was shown an ideal king called the exalted shepherd, who was given responsibility over many things by the god of the underworld.7 Nephi was similarly told that “there is one God and one Shepherd over all the earth” (1 Nephi 13:41), and in his vision the kingdom of Christ was celebrated (see v. 37).

Kummay saw strange symbolic objects, as did Nephi, and the god Nergal explained to Kummay some of what he was seeing, just as the Spirit of the Lord did for Nephi.8

In the Assyrian text, the god Nergal decreed broad destruction on Kummay’s people: “may distress, acts of violence and rebellion together bow you down so that, by their oppressive clamour, sleep may not come to you.”9 Nephi was similarly told that his people would experience calamities, and even that they would eventually be destroyed (1 Nephi 12:19–20).

In addition, Kummay was told that if he forgot this important god, then the god would “pass a verdict of annihilation” on him.10 This idea also occurs in the Book of Mormon (see 2 Nephi 1:20).

Biblical scholar Robert Gnuse has argued that some parts of the Old Testament, written in northern Israel, show signs of Assyrian influence. According to him, some of these texts date roughly 100 years before Lehi.11 Because Lehi was from the tribe of Manasseh, in northern Israel, these connections make sense. With this in mind, the similarities between this Assyrian text and the Book of Mormon suggest Nephi’s vision is not anachronistic or out of place. Nephi’s vision is similar to texts from the Ancient Near East that people like Lehi and Nephi would have known about.

Some material in the book of Isaiah helps to support this idea. Isaiah 24–27 is generally known as the “Isaiah Apocalypse,” and contains some ideas that one also finds in later apocalyptic literature. Many biblical scholars have assumed that this part of Isaiah was written many years after Lehi left Jerusalem. However, Christopher Hays has argued, based on the language of those chapters, that they were likely written well before Lehi left Jerusalem.12 Matthew Scott Stenson has noted that Isaiah 49:23–26 is similar to apocalyptic as well.13 This helps to explain how apocalyptic texts could have appeared in the Book of Mormon.

The Why

Because The Underworld Vision of an Assyrian Prince was not discovered until 1849, well after the Book of Mormon was published, the similarities between this ancient Assyrian text and the Book of Mormon serve as evidence for the authenticity of the Book of Mormon. Because of this historically early instance of apocalyptic experience and expression, it is not inappropriate to include Nephi’s account of his expansive vision in 1 Nephi 11–14 as apocalyptic.

The discovery of this Assyrian text does something else as well: it helps us see in Nephi’s writing one way that God communicates with His children. God could have answered Nephi’s prayer and explained Lehi’s vision using many modes of revelation and communication. But above all, God appears to have explained Lehi’s vision to Nephi in a manner that Nephi was likely familiar with. Because of texts like The Underworld Vision of an Assyrian Prince, Nephi could well have been already familiar with the rudiments of the early apocalyptic tradition, so when he experienced his vision, the way in which he experienced it would have made good sense to him.

We experience things similarly today.14 God reveals truths to us individually and to prophets speaking to us collectively today in ways that allow us to understand in our own cultural context, just as He did in ancient times. The Lord revealed in the early days of this dispensation of the gospel: “Behold, I am God and have spoken it; these commandments are of me, and were given unto my servants in their weakness, after the manner of their language, that they might come to understanding” (D&C 1:24). Applying this principle, BYU Professor Mark Wright has helpfully noted, “Modern Latter-day Saints believe in continuing revelation, collectively and individually, and cultural context continues to influence the manner in which divine manifestations are received by individuals entrenched within the various cultures that comprise the worldwide church.”15

Nicholas J. Frederick, “Mosiah 3 as an Apocalyptic Text,” Religious Educator 15, no. 2 (2014): 40–63.

Matthew Scott Stenson, “Lehi’s Dream and Nephi’s Vision Apocalyptic Revelations in Narrative Context,” BYU Studies Quarterly, 51, no. 4 (2012): 155–179.

Jared M. Halverson, “Lehi’s Dream and Nephi’s Vision as Apocalyptic Literature,” in The Things Which My Father Saw: Approaches to Lehi’s Dream and Nephi’s Vision (2011 Sperry Symposium), ed. Daniel L. Belnap, Gaye Strathearn, and Stanley A. Johnson (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2011), 53–69.

- 1. For more on apocalyptic, see Christopher Rowland, The Open Heaven: A Study of Apocalyptic in Judaism and Early Christianity (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 1982), 49–70; Klaus Koch, The Rediscovery of Apocalyptic (Naperville, IL: Allenson, 1970), 28; John J. Collins, “From Prophecy to Apocalypticism: The Expectation of the End,” in The Encyclopedia of Apocalypticism, ed. John J. Collins (Lexington: The Continuum Publishing Company, 1998), 1:145–159.

- 2. Isaiah 24–27, as well as Ezekiel are also seen as forerunners of apocalyptic. See Silviu Bunta, “In Heaven or on Earth: A Misplaced Temple Question About Ezekiel's Visions,” in With Letters of Light: Studies in the Dead Sea Scrolls, Early Jewish Apocalypticism, Magic, and Mysticism in Honor of Rachel Elior, ed. Daphna V. Arbel and Andrei A. Orlov, Ekstasis: Religious Experience from Antiquity to the Middle Ages, 2 (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2011), 28–44. Some have assumed that this material from Isaiah was written after Lehi’s time, however, linguistic analysis shows that it dates from before the time of Lehi. See Christopher Hays, “Hebrew Diachrony and Linguistic Dating in the Book of Isaiah,” presentation given at the 2017 Society of Biblical Literature Annual Meeting.

- 3. See Richard J. Clifford, “The Roots of Apocalypticism in Near Eastern Myth,” The Encyclopedia of Apocalypticism, 3 vols., ed. John J. Collins (New York, NY: Continuum Publishing Company, 2000), 1:14–15.

- 4. Clifford, “The Roots of Apocalypticism,” 1:15.

- 5. For more on the role of visions in apocalyptic, see Rowland, The Open Heaven, 70, as well as John J. Collins, “Toward the Morphology of a Genre,” Semeia 14 (1979): 9.

- 6. See Seth L. Sanders, “The First Tour of Hell: From Neo-Assyrian Propagands to Early Jewish Revelation,” Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions 9, no. 2 (2009): 157.

- 7. See Clifford, “The Roots of Apocalypticism,” 1:15.

- 8. See Clifford, “The Roots of Apocalypticism,” 1:15.

- 9. Alasdair Livingstone, Court Poetry and Literary Miscellanea, State Archives of Assyria 3 (Helsinki, FI: Helsinki University Press, 1989), 74.

- 10. Livingstone, Court Poetry, 74.

- 11. Robert Karl Gnuse, The Elohist: A Seventh-Century Theological Tradition (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2017), 63.

- 12. See Christopher Hays, “Hebrew Diachrony and Linguistic Dating in the Book of Isaiah,” SBL Presentation (Boston, MA, 2017).

- 13. Matthew Scott Stenson, “Lehi’s Dream and Nephi’s Vision Apocalyptic Revelations in Narrative Context,” BYU Studies Quarterly, 51, no. 4 (2012): 155–179.

- 14. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Does the Lord Speak to Men ‘According to Their Language’? (2 Nephi 31:3),” KnoWhy 258 (January 6, 2017).

- 15. Mark Alan Wright, “‘According to Their Language, unto Their Understanding’: The Cultural Context of Hierophanies and Theophanies in Latter-day Saint Canon,” Studies in the Bible and Antiquity 3 (2011): 65.