KnoWhy #661 | April 18, 2024

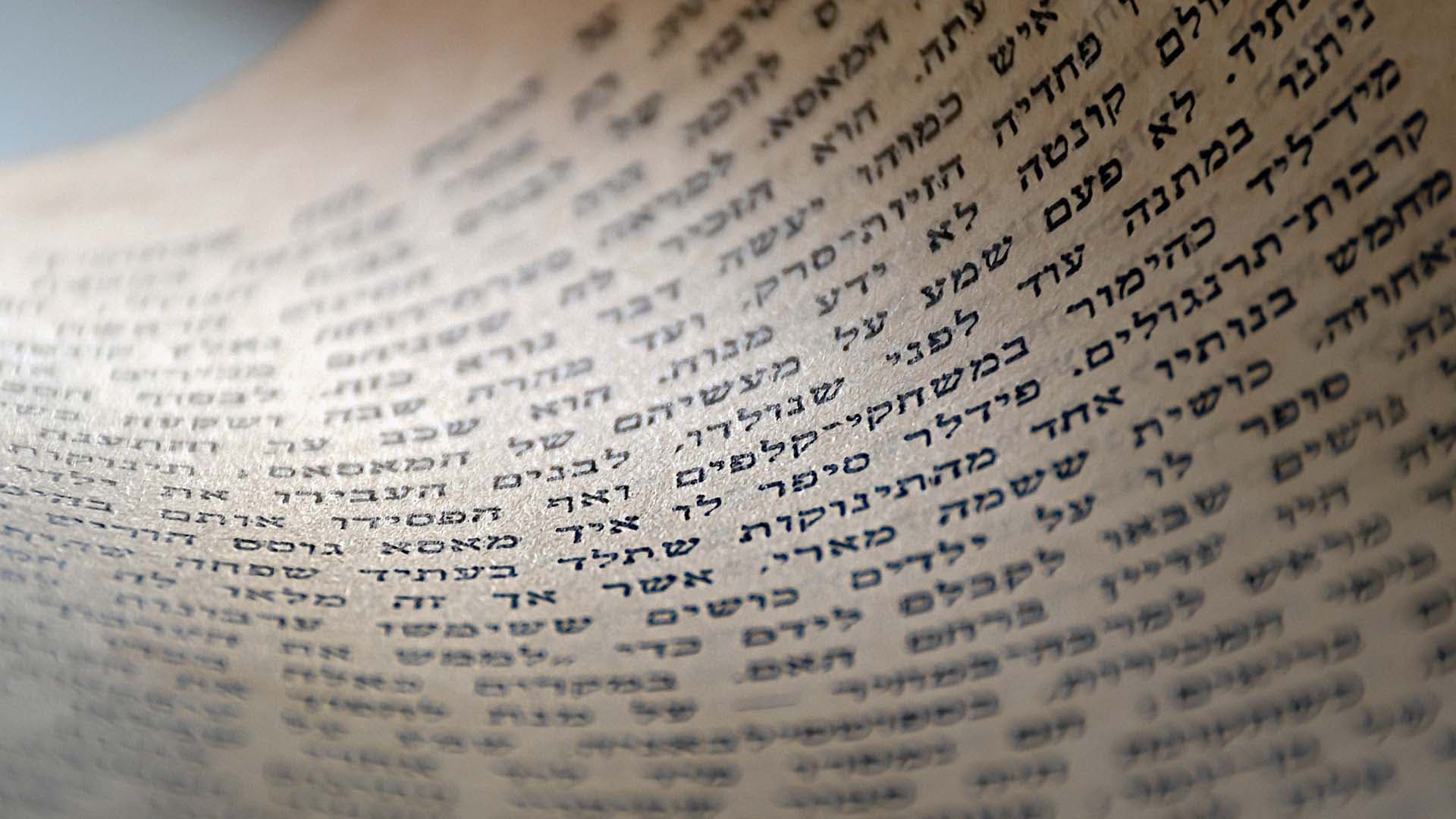

Why Are There Hebraisms in the Book of Mormon?

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

“And I saw the heavens open, and the Lamb of God descending out of heaven; and he came down and showed himself unto them. And I also saw and bear record that the Holy Ghost fell upon twelve others; and they were ordained of God, and chosen.” 1 Nephi 12:6–7

The Know

According to the Book of Mormon, that book was originally written in a form of Egyptian by authors who also knew and spoke Hebrew (see 1 Nephi 1:2; Mormon 9:32–33). Some scholars interpret this to mean that the Nephite authors wrote in Egyptian, while others believe they adapted an Egyptian script to write in Hebrew.1 Either way, this means that the original text was written in an ancient Near Eastern language despite being available only through modern translations, beginning with its divinely inspired English translation in 1829.

Many other ancient texts are also only available in a translated form, sometimes from manuscripts that date to long after the originals were composed.2 For example, the Apocalypse of Abraham has only been preserved in Slavonic, in manuscripts from between the fourteenth and seventeenth centuries AD.3 However, most scholars agree that it was originally composed in Hebrew or Aramaic between AD 70–150 based on numerous textual clues that appear to be dependent on a Semitic language.4

Hebraisms in the Apocalypse of Abraham

The linguistic features that provide evidence for a Hebrew or Aramaic original are often called Hebraisms or Semiticisms. Amy Paulsen-Reed has noted that among scholars who have studied the Apocalypse of Abraham, there is “a rare display of unity” concerning its Semitic origin.5

One textual clue supporting this view comes from the frequent use of the waw prefix, often translated as “and” or “but” in English.6 For example, Apocalypse of Abraham 11:4–5 reads: “And he said to me, Abraham. And I said, Here is your servant! And he said, Let my appearance not frighten you, nor my speech trouble your soul. Come with me! And I will go with you."7 Although this may feel repetitive to English speakers, this prefix was crucial in ancient Hebrew, which lacked punctuation and therefore needed some other way to distinguish between separate complete thoughts. Similarly, the phrase “and it came to pass” reflects a single word in Hebrew; it was commonly used as a temporal marker and is found prominently throughout the Apocalypse of Abraham.8

Another common Hebrew-like feature in the Apocalypse of Abraham is the metaphorical use of body parts to display an action or emotion.9 On one occasion, Abraham expressed concern by stating that “my heart was perplexed.”10 Other instances include “my spirit was amazed, and my soul fled from me” and “my soul has loved” God.11 Numerous other kinds of Hebraisms have been identified throughout the text.12

Since some features of the Apocalypse of Abraham suggest the Slavonic edition was translated from a Greek version of the text,13 some may be tempted to assume its Hebraisms are due to the use of biblicized Greek, meaning Greek that imitated the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible).14 One expert on the Apocalypse of Abraham considered this possibility but ultimately concluded, “The sheer number of Semitisms is best explained by this hypothesis [of a Semitic original].”15

Other textual details offer stronger evidence of a Semitic original that would make little sense as coming from biblicized Greek. For example, some quotations or allusions to the Bible found in the Apocalypse of Abraham appear to reflect the Hebrew Masoretic text (or the Aramaic Targums) rather than the Greek Septuagint.16 The expression “I said in my heart” (Apocalypse of Abraham 3:2) likely reflects the use of a Hebrew prepositional phrase that was not translated into the Targums or the Septuagint, making this a “true Hebraism.”17 Additional prepositional phrases invoke Hebrew syntax in ways not found in biblicized Greek.18

Some apparently Semitic words go untranslated in the Slavonic text.19 An instance of this is found in Apocalypse of Abraham 1:8, when Terah requests Abraham bring him his “axes and izmala,” likely a Hebrew word meaning “chisel.”20

Perhaps most compelling, however, is the presence of Hebrew or Aramaic names used in wordplays that would make sense only to a Semitic audience. For example, the name of the idol Barisat is likely derived from the Hebrew/Aramaic name bar ’eshāth, meaning “son of fire” or “fiery one.”21 This reconstruction is amusingly ironic, seeing that Barisat is itself burned with fire in Apocalypse of Abraham 5. The names of other idols each have a similar Semitic meaning that is “either descriptive of the idol’s role in the narrative or furthers the mockery of the idol in an ironic and humorous way.”22 The apparent puns involved in these names are “completely dependent” on the reader’s knowledge of the Semitic undertones.23

As noted previously, the combination of all these Semitic features and many others has led to a strong consensus among scholars, with one leading expert concluding that “the existence of the Semitic original of [the Apocalypse of Abraham] may be considered proven beyond any doubt.”24

Hebraisms in the Book of Mormon

Like the Apocalypse of Abraham, the Book of Mormon contains many linguistic features that are typical of ancient Near Eastern languages, including several examples similar to those found in the Apocalypse of Abraham.25

Donald W. Parry and other scholars have noted that the Book of Mormon frequently uses the waw prefix much like the Bible and other Hebrew texts do.26 This can be seen in the description Nephi gave of his vision early on in the Book of Mormon: “And I saw the heavens open, and the Lamb of God descending out of heaven; and he came down and showed himself unto them. And I also saw and bear record that the Holy Ghost fell upon twelve others; and they were ordained of God, and chosen” (1 Nephi 12:6–7).27 The phrase “and it came to pass” is likewise prominently used in the Book of Mormon in a manner typical of Hebrew writing.28

In addition, Book of Mormon authors sometimes employ imagery of body parts to convey great emotion, just as seen in the Apocalypse of Abraham. Mormon states that “my heart did begin to rejoice within me” when he believed the Nephites would repent (Mormon 2:12).29 Scholars have also pointed out the use of the cognate accusative, such as “dreamed a dream”; the construct state, such as “works of righteousness” instead of “righteous works”; and compound prepositions, such as “by the mouth of angels” instead of simply saying “by angels.”30 These and many other types and examples of Hebraisms are well documented.31

Similar Hebraisms occur in the King James Version of the Bible and can be found in other English-language works from the nineteenth century that imitate King James English.32 However, just as with the Apocalypse of Abraham, the sheer volume of Hebraisms found throughout the Book of Mormon should not be readily dismissed.

Furthermore, there are several other Hebraisms in the Book of Mormon not found in the King James Bible. For instance, Parry observes that “sometimes in the Book of Mormon and is used where but is expected.”33 One example of this is found in Omni 1:25, which states that “there is nothing which is good save it comes from the Lord: and [or but] that which is evil cometh from the devil.”34 According to Parry, “such examples are indicative of a literal translation from a Hebrew-like text”35 since in Hebrew, the waw prefix is used for both conjunctions, something not readily discernable to an English reader of the Bible.

Another example of a common Hebrew construction is the if-and clause.36 No examples of this conditional phrase are found in the King James Version or other modern English translations of the Bible,37 but they are found in the earliest manuscripts of the Book of Mormon. The earliest text for Mosiah 2:21 reads: “I say if ye should serve him with your whole soul—and yet ye would be unprofitable servants.”38 This led Parry to remark, “This finding underscores that the Book of Mormon’s use of Hebraistic literary forms cannot simply be attributed to Joseph Smith’s familiarity with the English Bible.”39

In some cases, biblical quotations in the Book of Mormon more closely reflect the Bible’s underlying Hebrew than the King James Version does. This can be seen in the writings of Nephi and Alma, each of which appears to be familiar with the Hebrew of Isaiah’s writings in ways unlikely known by Joseph Smith in 1829 due to his limited education at the time.40

Similar to the Apocalypse of Abraham, the Book of Mormon also contains some untranslated words that appear to be of Semitic origin.41 For instance, the word sheum appears in a list of grains and crops in Mosiah 9:9 and is similar to “a common Akkadian word referring to cereal grains.”42 The word ziff appears in a list of metals (see Mosiah 11:3, 8) and may be derived from a Hebrew root meaning “splendor, brightness” (ziv), or it could be related to the place name Ziph found in Joshua 15:24 (cf. 1 Chronicles 2:42; 4:16).43

Many Book of Mormon names have also been shown to have Semitic or Egyptian origins.44 Like other ancient texts, Book of Mormon names are used in wordplays that get lost in translation.45 For example, when Zeniff asks the Lamanite king if his people might “possess the land in peace,” the Lamanites give them “the land of Lehi-Nephi, and the land of Shilom” (Mosiah 9:5–6; emphasis added). The name Shilom is based on the Hebrew root shlm, meaning “peace.” Zeniff further uses this root in an ironic twist: there was ultimately no peace but rather war in the land of Shilom.46

This is only a small sample of proposed Hebraisms and other Semitic-like features found in the Book of Mormon. Many other examples could be given, including additional examples not immediately apparent in English translations of the Bible.47 Due to the high volume of these Near Eastern linguistic patterns, it would stand to reason that the Book of Mormon’s claims about its ancient Near Eastern origins ought to be taken seriously.

The Why

President Russell M. Nelson once observed, “The Book of Mormon is rich with Hebraisms—traditions, symbolisms, idioms, and literary forms.”48 In fact, the Book of Mormon has virtually all the same features that have convinced scholars that the Apocalypse of Abraham is a translation of an ancient Semitic text. As such, these features reasonably support the Book of Mormon’s claims to be an authentic, ancient text translated by the Prophet Joseph Smith from an ancient Near Eastern language.

According to Donald W. Parry, “It is highly doubtful that Joseph Smith knew anything about the Hebraic features of the Book of Mormon that have been identified by scholars long after his death.”49 Similarly, John Tvedtnes noted, “Many expressions used in the Book of Mormon are awkward or unexpected in English, even in Joseph Smith’s time. Yet they make good sense when viewed as translations, perhaps as too literal translations, from an ancient text written in a Hebrew-like language.”50

Such findings led Elder Jeffrey R. Holland to note that the Book of Mormon is a “text teeming with literary and Semitic complexity” that cannot be easily ignored by those who wish to seriously grapple with Joseph Smith’s prophetic mission.51 While the ultimate evidence for the Book of Mormon comes from the promptings of the Holy Ghost, recognizing the ancient literary techniques employed in its pages can help strengthen faith in its Christ-centered message.

Donald W. Parry, Preserved in Translation: Hebrew and Other Ancient Literary Forms in the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2020).

Stephen D. Ricks, Paul Y. Hoskisson, Robert F. Smith, and John Gee, Dictionary of Proper Names and Foreign Words in the Book of Mormon (Orem, UT: Interpreter Foundation; Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2022).

Matthew L. Bowen, Name as Key-Word: Collected Essays on Onomastic Wordplay and the Temple in Mormon Scripture (Orem, UT: Interpreter Foundation; Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2018).

Donald W. Parry, “Hebraisms and Other Ancient Peculiarities in the Book of Mormon,” in Echoes and Evidences of the Book of Mormon, ed. Donald W. Parry, Daniel C. Peterson, and John W. Welch (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2002), 155–190.

John A. Tvedtnes, “The Hebrew Background of the Book of Mormon,” in Rediscovering the Book of Mormon: Insights You May Have Missed Before, ed. John L. Sorenson and Melvin J. Thorne (Provo, Utah: FARMS, 1991), 77–91.

- 1. Stephen D. Ricks and John A. Tvedtnes, “Jewish and Other Semitic Texts Written in Egyptian Characters,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 5, no. 2 (1996): 156–163; John S. Thompson, “Lehi and Egypt,” in Glimpses of Lehi’s Jerusalem, ed. John W. Welch, David Rolph Seely, and Jo Ann H. Seely (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2004), 266–268; Neal Rappleye, “Learning Nephi’s Language: Creating a Context for 1 Nephi 1:2,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 16 (2015): 151–159; Robert F. Smith, Egyptianisms in the Book of Mormon and Other Studies (Provo, UT: Deep Forest Green, 2020), 1–13.

- 2. For a list of examples, see Daniel C. Peterson, “Editor’s Introduction: An Unapologetic Apology for Apologetics,” FARMS Review 22, no. 2 (2010): xii–xv.

- 3. Latter-day Saints have long been interested in the Apocalypse of Abraham. In fact, the first English translation of this text was published in the first volume of the Improvement Era. See R. T. Haag and E. H. Anderson, “The Book of the Revelation of Abraham,” Improvement Era 1 (August and September 1898): 705–714, 793–806.

- 4. See R. Rubinkiewicz, trans., “The Apocalypse of Abraham: A New Translation and Introduction,” in The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, 2 vols., ed. James H. Charlesworth (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1983), 1:681–683; Alexander Kulik, “Apocalypse of Abraham,” in Outside the Bible: Ancient Jewish Writings Related to Scripture, 3 vols., ed. Louis H. Feldman, James L. Kugel, and Lawrence H. Schiffman (Lincoln, NE: Jewish Publication Society, 2013), 2:1453–1455; Alexander Kulik, Retroverting Slavonic Pseudepigrapha: Toward the Original of the Apocalypse of Abraham (Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature, 2004), 61–76.

- 5. Amy Paulsen-Reed, The Apocalypse of Abraham in Its Ancient and Medieval Contexts (Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2022), 70.

- 6. Paulsen-Reed, Apocalypse of Abraham, 70.

- 7. Rubinkiewicz, “Apocalypse of Abraham,” 694; emphasis added.

- 8. Paulsen-Reed, Apocalypse of Abraham, 70; Rubinkiewicz, “Apocalypse of Abraham,” 682. See, for example, Apocalypse of Abraham 1:4, 7; 2:5; 5:11; 8:1; 10:1.

- 9. Paulsen-Reed, Apocalypse of Abraham, 70; Rubinkiewicz, “Apocalypse of Abraham,” 682.

- 10. Rubinkiewicz, “Apocalypse of Abraham,” 689 (Apocalypse of Abraham 1:4).

- 11. Rubinkiewicz, “Apocalypse of Abraham,” 693, 697 (Apocalypse of Abraham 10:2; 17:14).

- 12. For additional examples of Hebraisms in the Apocalypse of Abraham, see Arie Rubinstein, “Hebraisms in the Slavonic Apocalypse of Abraham,” Journal of Jewish Studies 4, no. 3 (1953): 108–115; Arie Rubinstein, “Notes and Communications: Hebraisms in the ‘Apocalypse of Abraham,’” Journal of Jewish Studies 5, no. 3 (1954): 132–135.

- 13. For example, Apocalypse of Abraham 10:11 refers to the realm of the dead as Hades rather than Sheol.

- 14. Paulsen-Reed, Apocalypse of Abraham, 71. For examples of biblicized Greek, see Jan Joosten, “Hebraisms in the Greek Versions of the Hebrew Bible,” in Encyclopedia of Hebrew Language and Linguistics, 4 vols., ed. Geoffrey Khan (Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2013), 2:196–198; David N. Bivin, “Hebraisms in the New Testament,” in Encyclopedia of Hebrew Language and Linguistics, 2:198–201.

- 15. Rubinkiewicz, “Apocalypse of Abraham,” 686. Paulsen-Reed, Apocalypse of Abraham, 71, 76, seems to agree with this conclusion.

- 16. Paulsen-Reed, Apocalypse of Abraham, 72. For examples, see Alexander Kulik, “Interpretation and Reconstruction: Retroverting the Apocalypse of Abraham,” Apocrypha 13 (2002): 216.

- 17. Paulsen-Reed, Apocalypse of Abraham, 70–71n2; Kulik, “Interpretation and Reconstruction,” 215.

- 18. For example, the phrase “it was heavy of a big stone” in Apocalypse of Abraham 1:5 would use the Hebrew min prefix and should be idiomatically understood to mean “it was heavier than a big stone.” Paulsen-Reed, Apocalypse of Abraham, 71. Additional phrases and discussions of this type of Hebraism can be found in Rubinstein, “Notes and Communications,” 132–135; Rubinstein, “Hebraisms in the Slavonic Apocalypse of Abraham,” 108–115; Rubinkiewicz, “Apocalypse of Abraham,” 682–683.

- 19. A similar phenomenon sometimes happens in the Septuagint, although not for the same words. For example, 1 Kings 18:32 LXX transliterates the Hebrew word tlh rather than translating it as “trench.”

- 20. Horace G. Lunt, “On the Language of the Slavonic Apocalypse of Abraham,” Slavica Hierosolymitana 7 (1985): 59; Rubinkiewicz, “Apocalypse of Abraham,” 689.

- 21. Paulsen-Reed, Apocalypse of Abraham, 74, notes that this name has parallels to Ugaritic and Phoenician deities. See also Alexander Kulik, “The Gods of Nahor: A Note on the Pantheon of the Apocalypse of Abraham,” Journal of Jewish Studies 54 no. 2 (2003): 228–229.

- 22. Paulsen-Reed, Apocalypse of Abraham, 76; see pp. 72–76 for a full discussion of the idols’ names. See also Kulik, “Interpretation and Reconstruction,” 214–215; Kulik, Retroverting Slavonic Pseudepigrapha, 72–74.

- 23. Paulsen-Reed, Apocalypse of Abraham, 72. For a study on the names of these idols, see Kulik, “Gods of Nahor,” 228–232.

- 24. Kulik, “Interpretation and Reconstruction,” 212; Kulik, Retroverting Slavonic Pseudepigrapha, 61. Paulsen-Reed, Apocalypse of Abraham, 76, repeats and affirms this conclusion.

- 25. As previously mentioned (see note 1), there is some debate as to whether the underlying language of the Book of Mormon is Hebrew or Egyptian, but for the purposes of this discussion the distinction is not necessary since according to Brian D. Stubbs, most Hebraisms “are also characteristic of other Near Eastern languages.” Brian D. Stubbs, “Language,” in To All the World: The Book of Mormon Articles from the Encyclopedia of Mormonism, ed. Daniel H. Ludlow, S. Kent Brown, and John W. Welch (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2000), 164. This includes Egyptian, as noted by John Gee, “La Trahison des Clercs: On the Language and Translation of the Book of Mormon,” Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 6, no. 1 (1994): 81n99. The few exceptions could be accounted for by the likelihood that if Nephi wrote in Egyptian, it “would more likely be a Hebraized Egyptian.” Sidney B. Sperry, “The Book of Mormon as Translation English,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 4, no. 1 (1995): 209. Matthew L. Bowen, “‘Most Desirable Above All Things’: Onomastic Play on Mary and Mormon in the Book of Mormon,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 13 (2015): 33, notes: “Hebraisms can exist in an Egyptian text.” See also Smith, Egyptianisms in the Book of Mormon, 15–85.

- 26. See Donald W. Parry, Preserved in Translation: Hebrew and Other Ancient Literary Forms in the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2020), 69–72; Donald W. Parry, “Hebraisms and Other Ancient Peculiarities in the Book of Mormon,” in Echoes and Evidences of the Book of Mormon, in Echoes and Evidences of the Book of Mormon, ed. Donald W. Parry, Daniel C. Peterson, and John W. Welch (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2002), 177–179; John A. Tvedtnes, “Hebraisms in the Book of Mormon,” in Encyclopedia of Hebrew Language and Linguistics, 2:195–196. See also Evidence Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Repeated Conjunctions,” Evidence #0311, February 15, 2022, online at evidencecentral.org.

- 27. Regarding the waw prefix, John A. Tvedtnes related an experience he had while attending the Hebrew University at Jerusalem: “This kind of repetition is so prominent in the Book of Mormon that Professor Haim Rabin, President of the Hebrew Language Academy and a specialist in the history of the Hebrew language, once used a passage from the Book of Mormon in a lecture in English to illustrate this principle, because, he explained, it was a better illustration than passages from the English Bible.” John A. Tvedtnes, “The Hebrew Background of the Book of Mormon,” in Rediscovering the Book of Mormon: Insights You May Have Missed Before, ed. John L. Sorenson and Melvin J. Thorne (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1991), 82.

- 28. According to Royal Skousen, “the original text of the Book of Mormon is closer to the Hebrew text of the Old Testament in having extra occurrences of the phrase ‘and it came to pass,’” while later editions of the Book of Mormon printed under Joseph Smith’s supervision removed them for readability. Royal Skousen, The History of the Text of the Book of Mormon: Grammatical Variation, part 1 (Provo, UT: FARMS; Provo, UT: BYU Studies, 2016), 166. For more on the use of the phrase “and it came to pass” in the Book of Mormon, see Parry, Preserved in Translation, 103–104; Parry, “Hebraisms and Other Ancient Peculiarities,” 163–164. Incidentally, Mayan writing also used a similar temporal marker, and thus “and it came to pass” could also be considered a Mayanism. See Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2008), 1:25–26.

- 29. Mormon also wrote that “meekness and lowliness of heart” was a prerequisite to the gift of the Spirit, again employing imagery of body parts. In another instance, Alma expresses “the wish of mine heart” (Alma 29:1) in emphatic terms (Alma 29:1). These kinds of Hebraisms have not received significant attention from Latter-day Saint scholars, though Melvin Deloy Pack notes that “heart(s)” is frequently used in both Hebrew and the Book of Mormon “due to its frequent use in metaphors.” Melvin Deloy Pack, “Hebraisms,” in Book of Mormon Reference Companion, ed. Dennis L. Largey (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2003), 325. Also, Paul Y. Hoskisson discusses an example involving the liver (often translated as “soul”) as the seat of emotions in Ugaritic and compares it to an expression involving the soul in the Book of Mormon. Paul Y. Hoskisson, “Textual Evidences for the Book of Mormon,” in First Nephi, The Doctrinal Foundation, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1988), 285. Compare the Hebraisms involving the “my soul” in the Apocalypse of Abraham mentioned above.

- 30. 1 Nephi 8:2; Alma 5:16; 13:22; Tvedtnes, “Hebrew Background,” 79–81; Tvedtnes, “Hebraisms in the Book of Mormon,” 2:195; Parry, Preserved in Translation, 105–110; Parry, “Hebraisms and Other Ancient Peculiarities,” 175–177. Although the expression “dreamed a dream” is found in the King James Version (see Genesis 37:5–9; 41:15), Dana M. Pike notes that Book of Mormon usage matches the nuances of its use in Hebrew in subtle ways. Dana M. Pike, “Lehi Dreamed a Dream: The Report of Lehi’s Dream in Its Biblical Context,” in The Things Which My Father Saw: Approaches to Lehi’s Dream and Nephi’s Vision, ed. Daniel L. Belnap, Gaye Strathearn, and Stanley B. Johnson (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book; Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2011), 95, 104.

- 31. For numerous other examples, see Parry, Preserved in Translation; Parry, “Hebraisms and Other Ancient Peculiarities,” 155–190; Tvedtnes, “Hebrew Background,” 77–91; Pack, “Hebraisms,” 321–325.

- 32. See Eran Shalev, “‘Written in the Style of Antiquity’: Pseudo-Biblicism and the Early American Republic, 1770–1830,” Church History: Studies in Christianity and Culture 79, no. 4 (December 2010): 800–826.

- 33. Parry, Preserved in Translation, 115.

- 34. See Parry, Preserved in Translation, 115–117, for other examples of this phenomenon, including some ands that in later editions of the text were changed to buts because it was more natural that way in English. See also Tvedtnes, “Hebrew Background,” 83–84, for additional examples, including 2 Nephi 1:20; 4:4, which contain the same covenant promise word-for-word, except one uses and while the other uses but. Only those familiar with the Hebrew language would recognize that the same term is used for both conjunctions in their translation.

- 35. Parry, Preserved in Translation, 115.

- 36. Parry, Preserved in Translation, 125–128; Daniel C. Peterson, “Not Joseph’s, and Not Modern,” in Echoes and Evidences, 212–214.

- 37. Examples of biblical passages reflecting this phrase but that were translated to be less awkward in English are shown in Parry, Preserved in Translation, 125–127.

- 38. Royal Skousen, ed., The Book of Mormon: The Earliest Text (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009), 197. Additional examples of this Hebraism are shown in Parry, Preserved in Translation, 127–128; Peterson, “Not Joseph’s,” 213. Note, especially, its occurrence seven times in the original text of Helaman 12:13–21. Many of these were removed from later editions of the Book of Mormon by the Prophet Joseph Smith for readability.

- 39. Parry, Preserved in Translation, 128.

- 40. See Book of Mormon Central, “Whose ‘Word’ Was Fulfilled by Christ’s Suffering ‘Pains and Sicknesses’? (Alma 7:11),” KnoWhy 564 (June 2, 2020); John A. Tvedtnes, “Isaiah Variants in the Book of Mormon,” in Isaiah and the Prophets: Inspired Voices from the Old Testament, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1984), 165–178. See also Evidence Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Joseph Smith’s Limited Education,” Evidence #0001, September 19, 2020, online at evidencecentral.org; Evidence Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Brass Plates Consistencies,” Evidence #0392, February 14, 2023, online at evidencecentral.org.

- 41. John A. Tvedtnes, “Untranslated Words in the Book of Mormon,” in The Most Correct Book: Insights from a Book of Mormon Scholar (Salt Lake City, UT: Cornerstone, 1999), 344–347.

- 42. Tvedtnes, “Untranslated Words,” 246. For additional discussion and possibilities, see Stephen D. Ricks, Paul Y. Hoskisson, Robert F. Smith, and John Gee, Dictionary of Proper Names and Foreign Words in the Book of Mormon (Orem, UT: Interpreter Foundation; Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2022), s.v. “sheum.”

- 43. See Tvedtnes, “Untranslated Words,” 344, for the meaning of Hebrew ziv. Note that this root (ziv) is also the name of a Hebrew month, which is rendered as “Zif” in 1 Kings 6:1, 37. The meaning of the Hebrew name Ziph is unknown, but according to Jerry Grover, Ziff, Magic Goggles, and Golden Plates: Etymology of Zyf and Metallurgical Analysis of the Book of Mormon Plates (Provo, UT: Grover Publishing, 2015), 34–35, the name could mean “(place of) casting metal” (quoting David Calabro). Grover also explores the potential etymology of ziff in greater detail and favors the Arabic zyf (derived from an earlier Aramaic or Hebrew cognate), which refers to forged coins or precious metals that have been debased (see p. 103 for a summary definition). See also Ricks et al., Dictionary of Proper Names, s.v. “ziff.”

- 44. See Ricks et al., Dictionary of Proper Names, for a thorough analysis of each name in the Book of Mormon and their likely etymologies.

- 45. See Matthew L. Bowen, Name as Key-Word: Collected Essays on Onomastic Wordplay and the Temple in Mormon Scripture (Orem, UT: Interpreter Foundation; Salt Lake City, UT: Eborn Books, 2018). For more examples of wordplay in the Book of Mormon, see Tvedtnes, “Hebraisms in the Book of Mormon,” 195; Stephen D. Ricks, “Converging Paths: Language and Cultural Notes on the Ancient Near Eastern Background of the Book of Mormon,” in Echoes and Evidences, 400–404; Parry, Preserved in Translation, 137–141. See also Evidence Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Wordplays (Sub-Category),” online at evidencecentral.org.

- 46. See Matthew L. Bowen, “‘Possess the Land in Peace’: Zeniff’s Ironic Wordplay on Shilom,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 28 (2018): 115–120; Evidence Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Shilom,” Evidence #0261, October 25, 2021, online at evidencecentral.org. Another possible wordplay can be found when the same root, shlm, is used in a piel construction to mean “reward” or “vengeance”: the Lamanite armies, who believed they had been wronged by the Nephites, sought out their vengeance in Shilom (see Mosiah 10:12–17). For this meaning of the name, see Ricks et al., Dictionary of Proper Names, 330–331.

- 47. Other examples of Hebraisms found in the Book of Mormon but that are not found (or are not immediately apparent) in the King James Bible include enallage and deflected agreement. See Kevin L. Barney, “Enallage in the Book of Mormon,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 3, no. 1 (1994): 113–147; Kevin L. Barney “Further Light on Enallage,” in Pressing Forward with the Book of Mormon: The FARMS Updates of the 1990s, ed. John W. Welch and Melvin J. Thorne, (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1999), 43–48; Andrew C. Smith, “Deflected Agreement in the Book of Mormon,” Journal of Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 21, no. 2 (2012): 40–57. For discussion of what Joseph Smith could have known about Hebraisms at the time of the translation of the Book of Mormon, see Parry, Preserved in Translation, xxv–xxvi.

- 48. Russell M. Nelson, “The Exodus Repeated” (Brigham Young University devotional, September 7, 1997).

- 49. Parry, Preserved in Translation, xxvi.

- 50. Tvedtnes, “Hebrew Background,” 91.

- 51. Jeffrey R. Holland, “Safety for the Soul,” October 2009 general conference.