KnoWhy #226 | August 21, 2019

What Do We Know about Mormon’s Upbringing?

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

“I perceive that thou art a sober child, and art quick to observe.” Mormon 1:2

The Know

Concerning Mormon’s record of his own life and ministry, Grant Hardy commented, “Finally, after three hundred pages with Mormon as our guide, we meet the man himself.”1 While limited in details, Mormon’s sketch of his formative years provides important clues concerning his personality and character. This information is particularly valuable because no other writer has influenced the text of the Book of Mormon more than Mormon himself,2 the prophet-historian who abridged the record into its current form.3

Mormon declared that he was a “descendant of Nephi” and that his “father’s name was Mormon” (Mormon 1:5). John L. Sorenson has proposed that Mormon likely “would have been the ranking member of his generation in a senior lineage or ‘house’ within the Nephite faction.”4 Mormon’s statement of lineage, therefore, helps establish him as a rightful heir and worthy record keeper.5

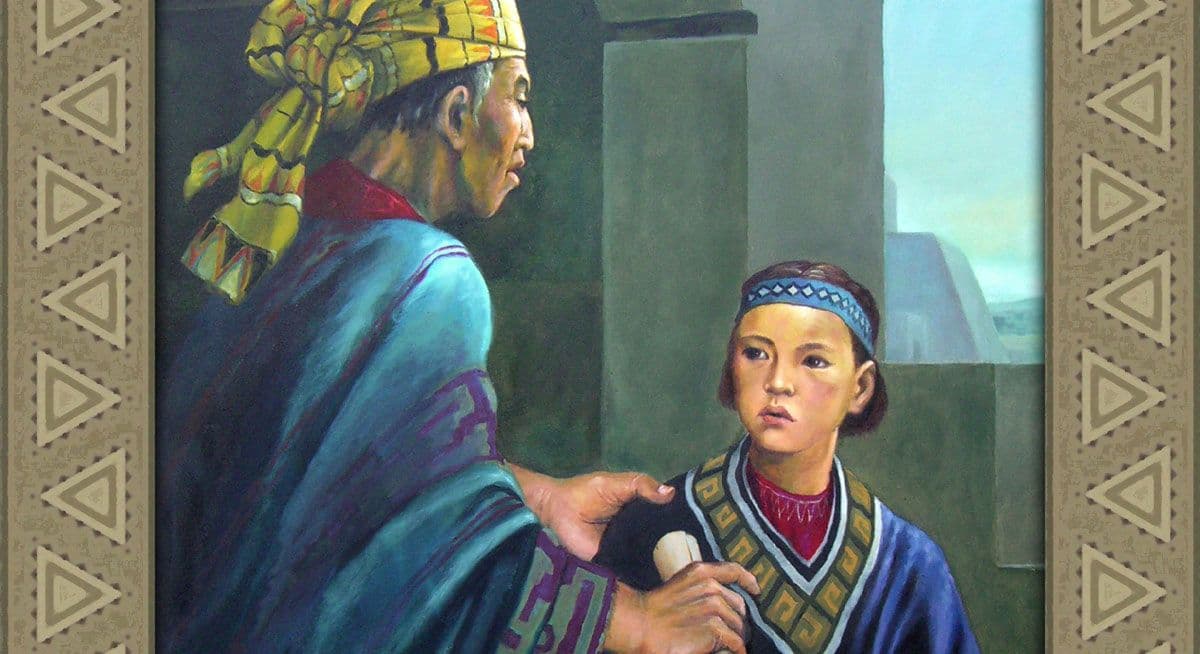

Ammaron, the previous record keeper, must have had enough interaction with Mormon to assess that Mormon (at ten years of age) was a “sober child”6 who was “quick to observe”7 (v. 2). Because of Mormon’s favorable qualities, Ammaron commissioned Mormon to retrieve the Nephite records when he turned “twenty and four years old” (v. 3) and to “engrave on the plates of Nephi all the things that ye have observed concerning this people” (v. 4).8

Although Mormon didn’t directly express it, readers can appropriately assume that being given such a lofty responsibility at such a tender age would have profoundly influenced him as a youth. Indeed, by the age of fifteen, Mormon was “visited of the Lord, and tasted and knew of the goodness of Jesus” (Mormon 1:15).9 At the age of sixteen, Mormon was chosen as the leader of the Nephite armies (Mormon 2:1–2). Apparently, Ammaron, the Lord, and Mormon’s people all saw something extraordinary in his capacity and character as a young man.

As far as secular learning goes, Mormon reported that when he was about ten years old, “I began to be learned somewhat after the manner of the learning of my people” (Mormon 1:2).10 The fact that this statement was in the context of Ammaron’s commission for him to become the next Nephite record keeper hints that at least some of Mormon’s learning was literary in nature. At age eleven Mormon was “carried by [his] father into the land southward, even to the land of Zarahemla” (v. 6).11 And throughout his military career, Mormon traveled among the lands of his people in order to defend them from the attacks of the Lamanites.12

These types of details suggest that from at an early age, Mormon gained military, geographic, and literary education—all crucial disciplines of knowledge for a prophet-historian in training. As Richard Holzapfel suggested, “Mormon had the best education his culture could furnish.”13 Sorenson similarly concluded, “Young Mormon came to maturity in the midst of a society revolutionizing itself. Because of his lofty priestly connections, his noble lineage, and the consequent high degree of literacy he must have commanded, he was thrust into a leadership role with which no average sixteen-year-old would ever have been entrusted.”14

A careful analysis of Mormon’s childhood thus demonstrates that education, travel, military leadership, emotional maturity, profound spiritual experiences, and unflagging righteousness in the face of adversity helped shape the prophet whose record would eventually “sweep the earth as with a flood” (Moses 7:62).15

The Why

Modern readers—especially young people—can learn much from Mormon’s stalwart example. Marilyn Arnold has commented, “It was nothing short of miraculous that a child born and reared in a society glutted with iniquity could remain spiritual, loving, and tenderhearted.”16 Elder Jeffrey R. Holland similarly concluded, “His faith, his hope, and his charity were irrepressible.”17 Mormon’s life thus aptly illustrates President Thomas S. Monson’s teaching that the righteous must sometimes dare to stand alone.18

For instance, right after noting that he was “fifteen years of age,” Mormon reported that he “did endeavor to preach unto this people” (Mormon 1:15–16). Then, in what must have been sorely disheartening, Mormon was “forbidden … [to] preach” because the people “wilfully rebelled against their God” (v. 16). Like many righteous young people, Mormon desired to serve a mission with his whole heart, but circumstances—specifically others’ choices, over which he had no control—denied him the opportunity.

Being one of the few faithful members of his community and also being forbidden to formally share his most deeply held values must have been terribly lonely. When he finally was able to preach to the people, Mormon reported that “it was in vain” because the people “did harden their hearts against the Lord their God” (Mormon 3:3). Mormon personally experienced rejection, and he knew what it felt like to stand alone in defense of the truth.

The way that Mormon’s apparent education and advanced literacy prepared him for his prophetic calling is also instructive. To young people, President Gordon B. Hinckley taught, “Do not short-circuit your education.”19 Elder Russell M. Nelson similarly declared, “Because of our sacred regard for each human intellect, we consider the obtaining of an education to be a religious responsibility.”20 Like Mormon, each child of God should educate and prepare themselves to do great, even seemingly impossible things while in mortality.21 As Elder Richard G. Scott declared, “Our Heavenly Father did not put us on earth to fail but to succeed gloriously.”22

It may have been tempting for those who rejected Mormon’s message to see him as a failure. In fact, Mormon himself at times seemed to have been deeply discouraged, even declaring at one point that “my joy was vain” because the people would not repent (Mormon 2:13). Yet readers of the Book of Mormon today recognize that Mormon’s mission was one of the greatest and most miraculous accomplishments in the history of the world. Elder Neil L. Andersen taught, “With our mortal eyes, we cannot judge the effect of our efforts, nor can we establish the timetable. When you share the love of the Savior with another, your grade is always an A+.”23

While certainly excruciating in the moment, Mormon’s life experiences gave him a unique capacity to compile the records of his people and to interpret them in way that would resonate with modern readers.24 As Thomas W. Mackay described it, “Mormon’s humanity, his anguish, and his individuality all resound from the pages of the book.’”25 Grant Hardy similarly described Mormon’s voice as “sorrowful, humane, moralistic, and precise.”26 It is this informed and compassionate voice—prepared, refined, and purified by the Lord—that continues to guide readers of the Book of Mormon throughout the world.

Matthew L. Bowen, “‘O Ye Fair Ones’ — Revisited,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 20 (2016): 315–344.

Thomas S. Monson, “Dare to Stand Alone,” Ensign, November 2011, 60–67, online at lds.org.

Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, “Mormon, the Man and the Message,” in The Book of Mormon: Fourth Nephi, From Zion to Destruction, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1995), 117–131.

- 1. Grant Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon: A Reader’s Guide (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2010), 93. Mormon’s personal record is technically not the first time he introduced himself in the text, but it is the first time that he discussed his personality, upbringing, and life experiences with any degree of depth. For an analysis of his other introductions, see Book of Mormon Central, “Why did Mormon Introduce Himself in 3 Nephi 5? (3 Nephi 5:12),” KnoWhy 194 (September 23, 2016); Book of Mormon Central, “Why Is ‘Words of Mormon’ at the End of the Small Plates? (Words of Mormon 1:3),” KnoWhy 78 (April 14, 2016).

- 2. See Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon, 90: “The somewhat late introduction of a new major voice—an editor working at the end of Nephite civilization—means that everything that follows has to be interpreted from the perspective of Mormon. Careful readers must constantly ask, ‘Why would Mormon choose to include this? What might he have omitted? Is there any significance in the way he arranges events or tells particular stories? And who is Mormon anyway?’”

- 3. For commentary which clarifies Mormon’s role as an abridger, see Brant A. Gardner, “Mormon’s Editorial Meta-Message,” FairMormon video presentation (time: 3:55–5:24), online at youtube.com.

- 4. John L. Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex: An Ancient American Book (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2013), 684. As an alternative to Sorenson’s view, Brant A. Gardner has noted, “Maya practice suggests that the literate were most likely nobles outside direct inheritance lines. This is, of course, exactly where my speculation would place Mormon.” See Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 6:49.

- 5. For additional analysis of Mormon’s name, heritage, and qualifications as a record keeper, see Book of Mormon Central, “Why did Mormon Introduce Himself in 3 Nephi 5? (3 Nephi 5:12),” KnoWhy 194 (September 23, 2016). See also, Gardner, Second Witness, 5:272–275.

- 6. Mormon’s self-assessment agreed with Ammaron’s praise: “I, being fifteen years of age and being somewhat of a sober mind” (Mormon 1:15). See also, D. Kelly Ogden and Andrew C. Skinner, Verse by Verse: The Book of Mormon, 2 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2011), 2:234: “Sober usually means possessing an earnestly thoughtful character, temperance, moderation, and showing no extreme qualities of fancy, emotion or prejudice.”

- 7. See Gardner, Second Witness, 6:49: “Ammaron’s description of Mormon as ‘quick to observe’ may mean that he learned quickly or was a bright student. In this case, Ammaron would have meant Mormon’s ability to read and write, required traits for a recordkeeper.” For a doctrinal application of “quick to observe,” see David A. Bednar, “Quick to Observe,” Ensign, December 2006, online at lds.org.

- 8. For a plausible relationship between Ammaron and Mormon, see Gardner, Second Witness, 6:48.

- 9. Mormon’s usage of the terms “visited,” “tasted,” and “knew” suggest that his experience with Jesus Christ was likely very personal and revelatory. See M. Catherine Thomas, “The Brother of Jared at the Veil,” in Temples of the Ancient World: Ritual and Symbolism, ed. Donald W. Parry (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1994), 394–397; David A. Bednar, “‘If Ye Had Known Me,’” Ensign, November 2016, 102–105, online at lds.org.

- 10. Interestingly, Mormon’s introduction mirrors Nephi’s self-introduction: “I, Nephi, having been born of goodly parents, therefore I was taught somewhat in all the learning of my father” (1 Nephi 1:1). For a discussion of how Nephi’s writings may have influenced Mormon’s autobiography, see Matthew L. Bowen, “‘O Ye Fair Ones’ — Revisited,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 20 (2016): 333–334. For a broader comparison of Nephi’s and Mormon’s editorial styles, see Grant Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon: A Reader’s Guide (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2010), 91–92; Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, “Mormon, the Man and the Message,” in The Book of Mormon: Fourth Nephi, From Zion to Destruction, ed. Monte S. Nyman and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1995), 128–129.

- 11. Considering that most eleven-year-olds are capable of walking long distances, the description of Mormon being “carried” by his father may seem rather odd. One possible explanation for this statement is that in ancient Mesoamerica, the social elite were often carried on litters or sedan chairs when traveling on special journeys. Mormon’s childhood education, scribal literacy, and precocious military attainments suggest that his father may have been a prominent social figure. See Book of Mormon Central, “What is the Nature and Use of Chariots in the Book of Mormon? (Alma 18:9),” KnoWhy 126 (June 21, 2016).

- 12. For examples of Mormon’s military travels, see Mormon 2:3–6, 16–17, 20–21; 4:2–3, 19–20; 5:3–7; 6:4.

- 13. Holzapfel, “Mormon, the Man and the Message,” 129.

- 14. John L. Sorensen, An Ancient American Setting for the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1985), 336.

- 15. See Ezra Taft Benson, “Flooding the Earth with the Book of Mormon,” Ensign, October 1988, online at lds.org.

- 16. Marilyn Arnold, “Mormon2,” in Book of Mormon Reference Companion, ed. Dennis L. Largey (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2003), 547.

- 17. Jeffrey R. Holland, “Mormon: The Man and the Book, Part 1,” Ensign, March 1978, online at lds.org. See also, Jeffrey R. Holland, “Mormon: The Man and the Book, Part 2,” Ensign, April 1978, online at lds.org.

- 18. Thomas S. Monson, “Dare to Stand Alone,” Ensign, November 2011, 60–67, online at lds.org.

- 19. Gordon B. Hinckley, “Four B’s for Boys,” Ensign, November 1981, online at lds.org.

- 20. Russell M. Nelson, “Where Is Wisdom?” Ensign, November 1992, online at lds.org.

- 21. See Russell M. Nelson, “Becoming True Millennials,” Worldwide Devotional for Young Adults, January 2016, online at lds.org.

- 22. Richard G. Scott, “How to Obtain Revelation and Inspiration for Your Personal Life,” Ensign, May 2012, 47, online at lds.org. Also quoted in Richard G. Scott, “Learning to Recognize Answers to Prayer,” Ensign, November 1989, online at lds.org.

- 23. Neil L. Andersen, “A Witness of God,” Ensign, November 2016, online at lds.org.

- 24. For example, Mormon seemed to select texts from what Phyllis Round called a “veritable library of engraved documents” in order to provide a supporting witness to the Bible—a book that he knew modern readers would be familiar with (see Mormon 9:7). See Phyllis Ann Roundy, “Mormon,” Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 4 vols., ed. Daniel H. Ludlow (New York, NY: Macmillan, 1992), 2:933.

- 25. Thomas W. Mackay, “Mormon and the Destruction of Nephite Civilization,” in The Book of Mormon, Part 2: Alma 30 to Moroni, ed. Kent P. Jackson, Studies in Scripture: Volume 8 (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1988), 321.

- 26. Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon, 97.