KnoWhy #256 | August 21, 2019

Was Nephi’s Slaying of Laban Legal?

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

“Therefore I did obey the voice of the Spirit, and took Laban by the hair of the head, and I smote off his head with his own sword.” 1 Nephi 4:18

The Know

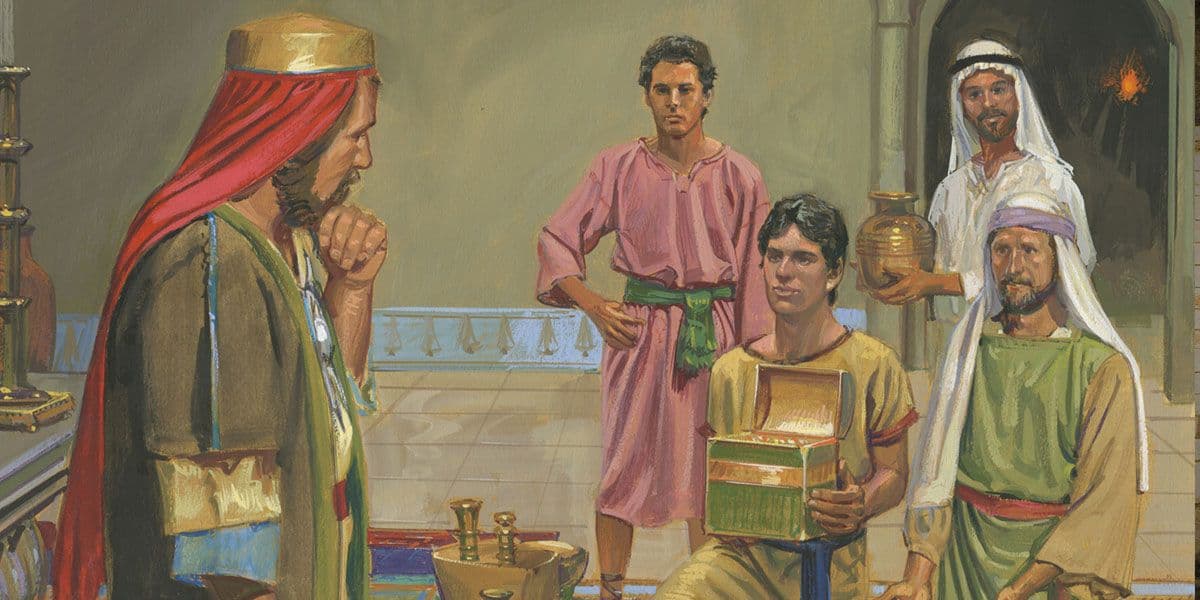

Shortly after leaving Jerusalem with his family, Nephi and his brothers returned to get a rare copy of the scriptures from a man named Laban (1 Nephi 3:2–4). The brothers tried twice to get the plates, to which Laban responded by trying to have them killed (v. 24–26). Finally, Nephi returned at night and found Laban passed out drunk (1 Nephi 4:7). After initially resisting the unexpected prompting (v. 10), Nephi killed Laban (v. 18), and managed to get the plates (v. 24).

This story can be as jarring to modern readers as it was disturbing to Nephi at the time (1 Nephi 4:10). Yet John W. Welch, a long-time student of biblical law, has argued that the complexities of “Nephi’s slaying of Laban can be evaluated profitably through the perspectives of the prevailing legal principles of Nephi’s day.”1

Even though such a killing would not be justifiable in most legal systems today, the text presents “several factors that substantially reduce Nephi’s guilt or culpability under the law of Moses as it was probably understood in Nephi’s day, around 600 BC.”2 Welch explained that the critical legal factors in this case are:

(1) State of mind—did the killer “lie in wait,” or “come presumptuously” with murderous intent?

(2) The role of divine will—did “God deliver him into his hand” (Exodus 21:12–14)?3

Unlike the modern definition, the ancient idea of premeditation required a murder to have been preplanned or implemented through treachery.4 From this Welch argued, “Several strong clues indicate that Nephi had the ancient definition in mind when he wrote the story of Laban.”5 Regarding his state of mind, Nephi specifically noted that he proceeded “not knowing beforehand the things which I should do” (1 Nephi 4:6).

As Welch has explained, this point demonstrates that Nephi had not necessarily even planned to find Laban, let alone to kill him. Nephi did not know where Laban would be, or that he would be drunk. “The occasion presented itself spontaneously. Nephi was completely surprised to find Laban. His deed was not preplanned and, therefore, not culpable.”6

And regarding the role of divine will, as Welch has written, “the ultimate reason for his action was God’s deliverance of Laban into Nephi’s hands. As the Spirit stated, it was the Lord who caused Laban’s death.”7 The specific words used in the text are important here. When Nephi stumbled upon Laban, the Spirit told Nephi to kill him. When Nephi resisted, the Spirit told Nephi again to “slay him, for the Lord hath delivered him into thy hands” (1 Nephi 4:12, emphasis added). This justification may refer to Exodus 21:13, which states that a slayer may flee to a city of refuge “if [he] lie not in wait, but God deliver him into his hand” (emphasis added). The striking parallel between these texts indicates that the Spirit may have been legally excusing Nephi for slaying Laban.8

One possible reason for this is because Laban committed three serious offenses against Nephi and his brothers. (1) He had falsely accused them of a capital crime (being “robbers,” 1 Nephi 3:13; Deuteronomy 19:16–19). (2) He had stolen their property, thus proving to be a robber himself (1 Nephi 3:25–26; 4:11). (3) He had not listened to the commandments of the Lord (1 Nephi 4:11; Deuteronomy 13:15).9

Thus, Nephi killed a man whom God had delivered into his hands, indicating that he was worthy of death from a divine perspective. Some killings in the Old Testament happened under similar circumstances. For example, the priest Phinehas killed Zimri and Cozbi for violating the law (Numbers 25:8). Amnon had violated his half-sister Tamar (2 Samuel 13:14-17), and his half-brother Absalom killed him because of it (v. 29).

Importantly, the Spirit provided yet another rationale for the act: “It is better that one man should perish than that a nation should dwindle and perish in unbelief” (1 Nephi 4:13). Welch has stated that this rationale “concerning the relative rights of the individual or the group also has a long tradition in biblical and Jewish legal history.”10 One example of this practice is the giving up of Samson to the Philistines (Judges 15:9–13). Extra-biblical tradition even suggests that the council of elders may have handed over Jehoiakim—a king of Judah at the time of Lehi—to Nebuchadnezzar in order to save the kingdom.11

The Why

It is important to look at ancient texts in their own context, not in a modern one. While the slaying of Laban is disturbing or uncomfortable for modern readers, “in its ancient legal context ... [it] makes sense, both legally and religiously, as an unpremeditated, undesired, divinely excusable, and justifiable killing—something very different from what people today normally think of as criminal homicide.”12 From this, Nephi was changed, seeing that God would provide a way for him to keep God’s commandments, no matter how impossible that appeared. Nephi also learned the importance of following the Spirit and staying within the rules that the Lord had revealed.

However, as convinced as Nephi was that his action was approved by God, Welch also noted that Nephi acted at considerable risk to himself: “I do not know if Nephi would have been able to persuade a court in Jerusalem to let him off or not, but I think he certainly saw himself as not having violated the law.”13

Indeed, the killing of Laban was not without penalties or consequences. In a case like Nephi’s, where the killing wasn’t preplanned, the killer still had to flee to one of the specifically-designated cities of refuge or leave the Holy Land (Numbers 35:6). Nephi did just that. In effect, his punishment for killing Laban was voluntary exile, an exile from which Nephi would never return.

It may also be important for readers to let the event impact them like it impacted Nephi.14 As Elder Holland noted, the narrative is

squarely in the beginning of the book—page 8—where even the most casual reader will see it and must deal with it. It is not intended that either Nephi or we be spared the struggle of this account. I believe that story was placed in the very opening verses of a 531-page book and then told in painfully specific detail in order to focus every reader of that record on the absolutely fundamental gospel issue of obedience and submission to the communicated will of the Lord. If Nephi cannot yield to this terribly painful command, if he cannot bring himself to obey, then it is entirely probable that he can never succeed or survive in the tasks that lie just ahead.15

Ultimately, one should avoid forcing God “into a box of our own making. Violence is intrinsic in this life, and, much as we might despise it, we should be wary of attempting to impose any kind of absolutes (from our point of view) on God.”16 This traumatic experience was difficult for Nephi, and this account, written several years later, likely captures years of wrestling with and reflection on his actions from legal, ethical, and political angles.17 Just as when Moses’s killing a man in Egypt (Exodus 2:11-15) marked the beginning of a new life of flight and separation from Egypt for himself and his people, Nephi’s traumatic experience opened the way toward a new land and life for him, his family, and all of his people as well.

Ben McGuire, “Nephi and Goliath: A Case Study of Literary Allusion in the Book of Mormon,” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 18, no. 1 (2009): 16–31.

John W. Welch and Heidi Harkness Parker, “Better That One Man Perish,” in Pressing Forward with the Book of Mormon: The FARMS Updates of the 1990s, ed. John W. Welch and Melvin J. Thorne (Provo, Utah: FARMS, 1999), 17–18.

John W. Welch, “Legal Perspectives on the Slaying of Laban,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 1, no. 1 (1992): 119–141.

Hugh Nibley, Lehi in the Desert/The World of the Jaredites/There Were Jaredites, The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley, Volume 5 (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1988), 94–104.

- 1. John W. Welch, The Legal Cases in the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press and the Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, 2008), 358.

- 2. John W. Welch, “Legal Perspectives on the Slaying of Laban,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 1, no. 1 (1992): 121.

- 3. Legal Perspectives,” 123.

- 4. Welch, “Legal Perspectives,” 124.

- 5. Welch, “Legal Perspectives,” 124.

- 6. Welch, “Legal Perspectives,” 125.

- 7. Welch, “Legal Perspectives,” 131.

- 8. See Book of Mormon Central, “Why Was Helaman’s Servant Justified In Killing Kishkumen? (Helaman 2:9),” KnoWhy 173 (August 25, 2016).

- 9. See Welch, “Legal Perspectives,” 131, 137; John A. Tvedtnes, The Most Correct Book: Insights from a Book of Mormon Scholar (Salt Lake City, UT: Cornerstone Publishing, 1999), 104–105; Taylor Halverson, “Reading 1 Nephi With Wisdom,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 22 (2016): 291–292.

- 10. Welch, “Legal Perspectives,” 134.

- 11. See John W. Welch and Heidi Harkness Parker, “Better That One Man Perish,” in Pressing Forward with the Book of Mormon: The FARMS Updates of the 1990s, ed. John W. Welch and Melvin J. Thorne (Provo, Utah: FARMS, 1999), 17–18.

- 12. Welch, “Legal Perspectives,” 140–141.

- 13. John W. Welch, “Introduction,” Studia Antiqua 3, no. 2 (2003): 12.

- 14. David Baron, Social Ethics of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints: Analysis and Critique (Los Angeles, CA: University of Southern California, 2004), 84–87.

- 15. Jeffrey R. Holland, “The Will of the Father in All Things,” BYU Speeches, January 17, 1989, online at speeches.byu.edu.

- 16. Gregory Dundas, review of By Study and Also by Faith, Vol. 2, edited by John M. Lundquist and Stephen D. Ricks, Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 4 (1992): 131.

- 17. On the political aspects of the Laban story, see Noel B. Reynolds, “The Political Dimension in Nephi’s Small Plates,” BYU Studies 27, no. 4 (1987): 22–25; Val Larsen, “Killing Laban: The Birth of Sovereignty in the Nephite Constitutional Order,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 16, no. 1 (2007): 26–41, 84–85.