Evidence #397 | March 21, 2023

Book of Mormon Evidence: Salt

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

Abstract

In his resurrected ministry at the temple in Bountiful, Jesus made several references to salt, similar to those given in the Sermon on the Mount. His sayings would have been well-understood in an ancient Mesoamerican context, where salt was a crucial commodity.Salt in the Bible and Book of Mormon

Throughout the Old and New Testaments, salt is mentioned dozens of times.1 In ancient Israel, it was used as a seasoning and preservative,2 as well as a means of causing environmental desolation.3 It also symbolized hospitality and was associated with covenants.4 Perhaps the most well-known biblical reference to salt is found in Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount, in which he compared his followers to the “salt of the earth” (Matthew 5:13).

In his resurrected ministry in the Americas, Jesus delivered essentially the same message, with only slight variation: “Verily, verily, I say unto you, I give unto you to be the salt of the earth; but if the salt shall lose its savor wherewith shall the earth be salted? The salt shall be thenceforth good for nothing, but to be cast out and to be trodden under foot of men” (3 Nephi 12:13). Several chapters later, Jesus applied this imagery to the Gentiles, declaring that if they “will not turn unto me,” then God would allow the house of Israel to “tread them down, and they shall be as salt that hath lost its savor” (3 Nephi 16:15).5

In contrast to the extensive references to salt in the Bible, these are the only two verses in the Book of Mormon that mention salt. This may lead one to wonder: Would Christ’s teachings have made sense in an ancient American context? Did people in the New World even have access to salt? And if so, how was it used?

Salt in Ancient Mesoamerica

In Mesoamerica, where many researchers believe the primary events of the Book of Mormon took place, salt was a crucial commodity and served various functions, as has been documented in numerous recent publications.6 Because of the tropical climate in this region (resulting in a substantial loss of bodily salt through sweat) and because of the presumably limited extent of domesticated animals (through which many societies obtain their necessary salt intake), many Mesoamerican societies were likely in constant need of supplemental dietary salt.7 According to Eduardo Williams,

Olmec traders actively engaged in salt extraction and trade along the Gulf coast in the Formative [period], and by 1200 B.C. Olmec merchants from the Gulf of Mexico had penetrated highland and Pacific coastal Guatemala, Oaxaca, and central Mexico in their quest for salt and various other strategic resources. … During the Middle Formative period (ca. 900–300 B.C.) the production of salt by boiling brackish spring water in pottery jars was a common activity. Salt making was probably one of Formative Mesoamerica’s most widespread regional specializations.8

Robust salt production then continued into the Classic and Postclassic eras, as evidenced from numerous sites.9 Particularly important was the “coastal Yucatán, where salt was obtained through solar evaporation.”10

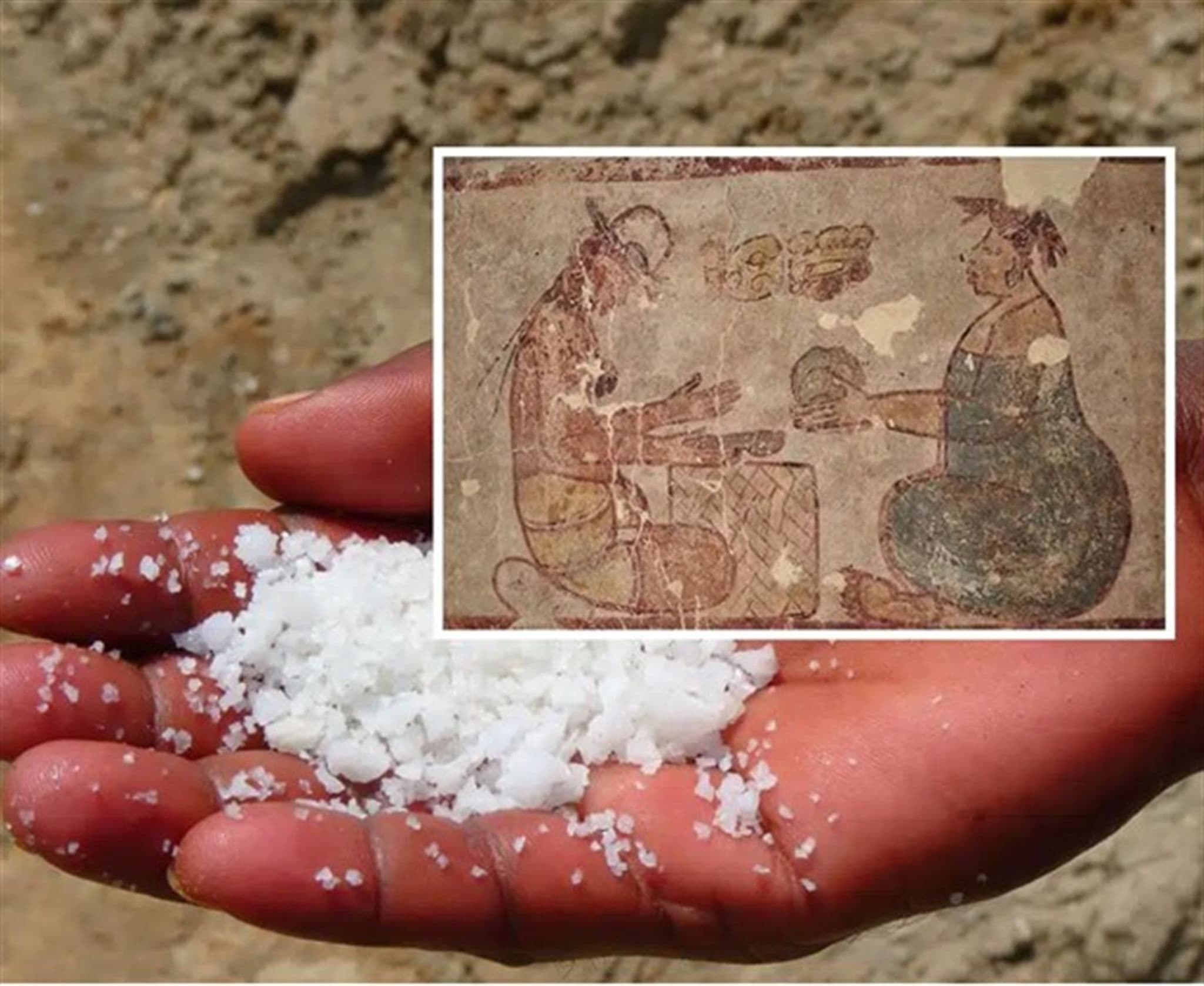

Yet to Mesoamerican peoples, salt wasn’t just a crucial dietary need or culinary want. Its preservative properties were apparently well-known and utilized, allowing for long-term storage and long-distance transportation of various types of meat, especially fish.11 Salt also played an important role in the production of dyed cloth,12 and it may have even been used as a type of currency or medium of exchange, especially in its form as a fire-hardened cake or loaf. Such a cake, accompanied by the hieroglyphic symbol for “salt,” has been identified on a mural from Calakmul, Mexico, dating to more than 2,500 years ago.13

According to Heather McKillop,

As a valuable commodity in a standard size that could be counted, divided, and stored, salt cakes would have been valued as a standard quantity of other commodities. As commodities that everyone valued because they needed it, the average Maya family may have had a salt cake in reserve for future purchases by barter or by perhaps using it as money.14

Saltworks were so important, in fact, that “wars were fought over their possession and control.”15 Williams concluded that the “procurement of salt and other strategic resources, as well as their distribution, the military control over source areas, and the extraction of tributes, were critical aspects for the economic and social life of [various] Mesoamerican polities.”16

Conclusion

Salt played a crucial role in ancient Mesoamerica during the period in which the Book of Mormon took place. Societies living in this region regularly used salt to enhance the flavor of their meals, but they also likely would have recognized it as a valuable preservative, a crucial component of their textile industry, and perhaps even as a commodity with bartering or purchasing power. They would therefore have been prepared to understand Christ’s metaphorical message involving this unique and valuable substance.17

- 1. A basic search of the King James Bible using WordCruncher shows that forms of the word salt occur 47 times in more than 20 different books.

- 2. See Job 6:6; Leviticus 2:13.

- 3. See Judges 9:45.

- 4. See Ezra 4:14; Numbers 18:19; 2 Chronicles 13:5.

- 5. Evidence on Sermon.

- 6. See Heather McKillop and E. Cory Sills, “Household Salt Production by the Late Classic Maya: Underwater Excavations at Ta’ab Nuk Na,” Antiquity 96 (2022): 1232–1250; Heather McKillop, “Salt as a Commodity or Money in the Classic Maya Economy,” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 62 (2021): 1–9; Carolyn Freiwalda, Brent K.S. Woodfill, Ryan D. Mills, “Chemical Signatures of Salt Sources in the Maya World: Implications for Isotopic Signals in Ancient Consumers,” Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 27 (2019): 1–8; Heather Irene McKillop, Maya Salt Works (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2019); Cory Sills and Heather McKillop, “Specialized Salt Production During the Ancient Maya Classic Period at Two Paynes Creek Salt Works, Belize: Chan b’i and Atz’aam Na,” Journal of Field Archaeology 43 (2018): 457–471; Heather McKillop and Kazuo Aoyama, “Salt and Marine Products in the Classic Maya Economy from Use-Wear Study of Stone Tools,” PNAS (2018): 10948–10952; Heather McKillop, “Underwater Archaeology, Salt Production, and Coastal Maya Trade at Stingray Lagoon, Belize,” Latin American Antiquity 6, no. 3 (2017): 214–228; Cory Sills, Heather McKillop, and E. Christian Wells, “Chemical Signatures of Ancient Activities at Chan b’i - A Submerged Maya Salt Works, Belize,” Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 9 (2016): 654–662; E. Cory Sills, “Re-evaluating the Ancient Maya Salt Works at Placencia Lagoon, Belize,” Mexicon 38, no. 3 (2016): 69–74; Edwardo Williams, “Salt Production and Trade in Ancient Mesoamerica,” in Pre-Columbian Foodways: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Food, Culture, and Markets in Ancient Mesoamerica, ed. John Edward Staller and Michael Carrasco (New York, NY: Springer, 2010), 170–190; Mark Robinson and Heather McKillop, “Fuelling the Ancient Maya Salt Industry,” Economic Botany 68 (2014): 96–108; Elizabeth Cory Sills, “Underwater Excavations of Two Ancient Maya Salt Works, Paynes Creek National Park, Belize” (Dissertation, Louisiana State University, 2013); Tamara L. Spann, “Salt of the Maya: Evidence of Prehispanic Salt Production and Architectural Function at the Eleanor Betty Site, Paynes Creek National Park, Belize” (Master’s Thesis, Louisiana State University, 2012); Satoru Murata, “Maya Salters, Maya potters: The Archaeology of Multicrafting on Non-residential Mounds at Wits Cah Ak’ Al, Belize” (Dissertation, Boston University, 2011); Ashley L. Hallock, “Paleoenvironmental Investigations Near Hattieville, Central Belize: Implications for Ancient Maya Salt Production” (Master’s Thesis, Washington State University, 2009); Heather McKillop, “One Hundred Salt Works! The Infrastructure of the Ancient Maya Salt Industry,” Research Reports in Belizean Archaeology 5 (2008): 251–260; Heather McKillop, “Classic Maya Workshops: Ancient Salt Works in Paynes Creek National Park, Belize,” Research Reports in Belizean Archaeology 2 (2005): 279–289; Heather McKillop, “Finds in Belize Document Late Classic Maya Salt Making and Canoe Transport” PNAS 102, no. 15 (2005): 5630–5634.

- 7. See Williams, “Salt Production and Trade in Ancient Mesoamerica,” 177.

- 8. Williams, “Salt Production and Trade in Ancient Mesoamerica,” 176.

- 9. See Williams, “Salt Production and Trade in Ancient Mesoamerica,” 179–184. See also Freiwalda, Woodfill, and Mills, “Chemical Signatures of Salt Sources in the Maya World,” 1–8.

- 10. Williams, “Salt Production and Trade in Ancient Mesoamerica,” 183.

- 11. Williams, “Salt Production and Trade in Ancient Mesoamerica,” 177–178.

- 12. Williams, “Salt Production and Trade in Ancient Mesoamerica,” 179.

- 13. See Ramón Carrasco Vargas, Verónica A. Vázquez López, and Simon Martin, “Daily Life of the Ancient Maya Recorded on Murals at Calakmul, Mexico,” PNAS 106, no. 46 (2009): 19248; Louisiana State University, “Mural Painted More Than 2,500 Years Ago Depicts Salt as an Ancient Maya Commodity at a Marketplace,” online at scitechdaily.com.

- 14. Heather McKillop, “Salt as a Commodity or Money in the Classic Maya Economy,” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 62 (2021): 7.

- 15. Williams, “Salt Production and Trade in Ancient Mesoamerica,” 176. The author further explains, “The Maya site of Emal, the richest salt deposit in coastal Yucatán, was fortified to repel enemy incursions. Elsewhere in Mesoamerica salt was used as a powerful political tool; Muñoz Camargo relates how the Aztecs tried to conquer the province of Tlaxcala by siege, depriving the Tlaxcaltecans of many goods such as cotton, gold, silver, green feathers, cacao and salt. This siege lasted for over seventy years, and as a result the Tlaxcaltecans supposedly became accustomed to eating without salt” (p. 176).

- 16. Williams, “Salt Production and Trade in Ancient Mesoamerica,” 188.

- 17. It should be noted that the validity of the Book of Mormon doesn’t rest on salt having been a well-known substance in ancient America. Book of Mormon peoples would have been familiar with the content of the brass plates, which surely had references to salt. So, in theory, they could have understood (at least to some extent) Jesus’s references to salt through their religious heritage, rather than through first-hand cultural or economic interactions with it. That being said, his words would undoubtedly have been more meaningful for a society intimately familiar with salt and its distinctive qualities.