Evidence #347 | June 13, 2022

Book of Mormon Evidence: Foundation Deposits

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

Abstract

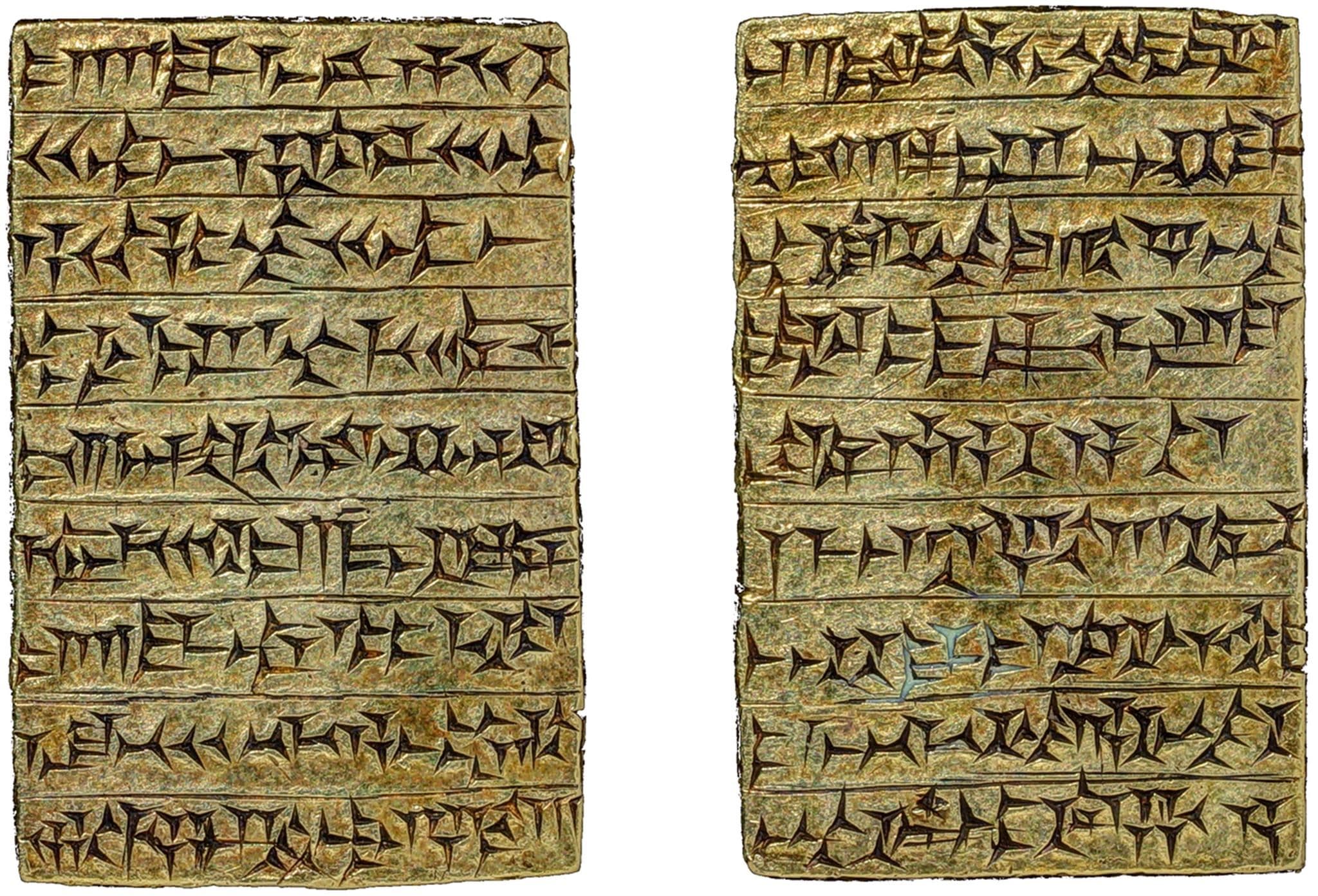

Mesopotamian foundation deposit inscriptions on metal plates correspond with the Book of Mormon in significant ways.Descriptions of plates in the Book of Mormon suggests that the practice of inscribing some important documents on metal likely existed in the ancient Near East previous to 600 BC (1 Nephi 3:3; 5:10–14). The discovery of metal documents made after the publication of the Book of Mormon provide significant correspondences. Mesopotamian foundation plates represent an interesting example of this early practice.

Mesopotamian Foundation Deposits

When ancient Mesopotamian rulers constructed palaces or temples, they sometimes interred within the walls or lower structures of these buildings objects described by scholars as foundation deposits. These included valuable objects of stone, jewels, or metal, which sometimes included inscriptions briefly referencing the deeds of the ruler and praising the gods. Sometimes these were inscribed on metal plates.1

Gold and Silver Tablets of Shalmaneser and Tukulti-Ninurta

The earliest example is a small gold tablet from the reign of Shalmaneser I (1274–1245 BCE). This tablet and two others from the reign of Tukulti-Ninurta I (1244–1208 BCE) were discovered at the time of Shalmaneser III (858–824 BCE) and reburied together. They were rediscovered in the early Twentieth Century in the lower room of a structure resting on a bed of sand in a small bowl.”2 Another bowl was then placed over the first and laced shut much like a modern time capsule.3 The ownership of the older tablet, which is “smaller than a credit card,” has been the subject of some controversy.4

Gold and Silver Tablets of Assurnasirpal II.

Two small gold and a silver tablets of Assurnasirpal II (883–859 BC) are part of the Babylonian Collection at Yale. The identical inscription on both plates states, “I laid its (the palace’s) foundations on tablets of silver and gold.”5 Pearce observes that “the inscriptions are unusual, for they are among the few instances that conspicuously mention the materials upon which the text is inscribed.”6 According to Ferris Stephens, the two tablets may have at one time been enclosed in a stone box made for that purpose.7

Tablets of Sargon II.

Archaeologists in 1854, working on the foundation of a ruined palace at of Sargon II (722–705 BC) at Khorsabad, discovered a chest containing six inscribed tablets. Two of these, one of which was made of lead, are now lost. The four remaining tablets were made of gold, silver, bronze, and magnesite.8 The tablets contain an inscription from Sargon II which state, “on tablets of gold, silver, bronze, lead, magnesite, lapis lazuli and alabaster I inscribed my name and I placed these in their foundation walls.”9

Tablet of Esarhaddon

In an inscription of Esarhaddon (681–669 BC) published in English in 1927, the king recorded, “I had memorial steles (tablets) made of silver, gold, copper, lapis lazuli, marble, salamdu (some black stone), ‘wheat’ stone (Fusulina limestone), elalu-stone (and) white limestone …. I engraved upon them. The might of the great warrior, Marduk, the deeds which I had accomplished, the works of my hands. I wrote thereon and put them into the foundations. I turned them over to (lit., left them for) the future (eternity).”10

Babylonian Tablets

Two Babylonian foundation tablets with identical inscriptions from the temple at Larsa are in the British Museum in London. Both tablets were inscribed on both sides. One is copper and the other is of limestone. The copper plate is a dedicatory inscription which originally contained 28 lines of text.11

Persian Tablets

In 1933 Ernst Herzfeld, during excavations at the site of Persepolis, discovered two stone boxes which had been buried within the walls at the corners of one of the main halls of the palace. Each box contained a single square plate, one of gold and the other of silver, from Darius I king of Persia (550–486 BC). The plates, each of which is 13 x 13 inches (33 x 33 cms.), contain identical inscriptions in the Persian, Elamite, and Akkadian scripts. The plates proclaim Darius as King of Kings and offer a plea that the god Ahuramazda may protect him and his house.12

Audiences Past and Future

Inscriptions on foundation deposits are relatively brief, but the expensive material upon which they are recorded point to the importance they had for ancient Mesopotamian rulers who viewed them as an offering to the gods. According to Pearce, these foundation inscriptions were believed by ancient rulers to “establish for eternity the devotion of the donor; in return for this expression of piety, he hoped to receive the fulness of the beneficiences the invoked deity might offer.”13

While some scholars believe that such inscriptions were “purely commemorative” and had no intended purpose beyond that of a private offering,14 others such as Christina Tsouparopoulou have suggested that they were intended to convey messages to future finders of the texts. They were “meant to pass on a royal message to future rulers unearthing these deposits in the course of their own building activities … It is possible that there was an intended audience, far into the future, and that this act recorded the ruler who commissioned and built those temples for posterity.”15

Correlations with the Book of Mormon

While foundation deposits on gold, silver, and bronze differ in some ways from plates described in the Book of Mormon, other correspondences are noteworthy. First, as with the case of ancient Near Eastern treaties on bronze plates, they show that the practice of inscribing texts on metal is ancient, predating the time of Lehi and the plates of brass by several centuries.

Second, this evidence shows that the practice of concealing metal inscriptions in stone boxes was known in the ancient Near East as well (Joseph Smith History 1:52).16

Third, while the plates known to the Nephites were not, strictly speaking, offerings to the gods, and had a practical purpose as archival records, Nephite prophets did consider their work to be divinely sanctioned and guided and that the strenuous efforts to record and preserve the plates were accepted and blessed by God. As Nephi wrote, “I know that the Lord God will consecrate my prayers for the gain of my people. And the words which I have written in weakness will be made strong unto them” (2 Nephi 33:4).

Fourth, some Book of Mormon scribes, such as Mormon and his son Moroni, directly address and give commandments to future custodians of the plates such as Joseph Smith (though not mentioned by name), with appropriate instructions and cautions (Ether 5:1–6).

Fifth, like some examples from ancient Mesopotamia, Nephite scribes sometimes reference the very materials upon which the plates are made. When Nephi describes how he made his first record on plates of ore, he first mentions that he found ore of gold, silver, and copper, perhaps indicating that the plates were formed of a compound of these substances (1 Nephi 18:25; 19:1). All of these correspondences point to an ancient background which may have influenced the Nephite scribal tradition.

Conclusion

The ancient Mesopotamian practice of embedding inscribed metal plates into the foundations of sacred structures has several parallels with the metal recordkeeping traditions perpetuated by Nephite scribes. This enhances the believability of the Book of Mormon as a genuine ancient document created by a society that inherited a Near Eastern literary tradition. Notably, the Mesopotamian foundation plates were all discovered long after the Book of Mormon was first published. It is therefore impossible that Joseph Smith’s story of the buried gold plates drew upon knowledge of this ancient practice.

Book of Mormon Central, “Is the Book of Mormon Like Other Ancient Metal Documents? (Jacob 4:2),” KnoWhy 512 (April 25, 2019).

Book of Mormon Central, “Are There Other Ancient Records Like the Book of Mormon? (Mormon 8:16),” KnoWhy 407 (February 13, 2018).

William J. Hamblin, “Sacred Writing on Metal Plates in the Ancient Mediterranean,” FARMS Review 19, no. 1 (2007): 37–54.

H. Curtis Wright, “Ancient Burials of Metal Documents in Stone Boxes,” in “By Study and Also By Faith”: Essays in Honor of Hugh Nibley, 2 vols., ed. John M. Lundquist and Stephen D. Ricks (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1990), 273–334.

H. Curtis Wright, “Metallic Documents in Antiquity,” BYU Studies Quarterly, 10, no. 4 (1970): 457–477.

Book of Mormon

Pearl of Great Price

- 1. One of the standard sources on the topic is Richard S. Ellis, Foundation Deposits in Ancient Mesopotamia (New Haven, CT. and London: Yale University Press, 1968).

- 2. Ellis, Foundation Deposits in Ancient Mesopotamia, 97–98, 191–192; Laurie E. Pearce, “Materials of Writing and Materiality of Knowledge,” in Gazing on the Deep: Ancient Near Eastern and Other Studies in Honor of Tzvi Abusch, ed. Jeffrey Stackert, Barbara Nevling Porter, David P. Wright (Bethesda, MD: CDL Press, 2010), 172.

- 3. Ellis, Foundation Deposits in Ancient Mesopotamia, 98; Pearce, “Materials of Writing and Materiality of Knowledge,” 172.

- 4. Michael Virtanen, “Assyrian Gold Tablet Must Go Back to Germany, NY Court Rules,” Science News, November 14, 2013.

- 5. Ellis, Foundation Deposits in Ancient Mesopotamia, 100.

- 6. Pearce, “Materials of Writing and Materiality of Knowledge,” 173.

- 7. Ferris J. Stephens, “The Provenance of the Gold and Silver Tablets of Ashurnasirpal,” Journal of Cuneiform Studies 7, no. 2 (1963): 73–74. See also, Evidence Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Ancient Records Hidden in Boxes,” Evidence# 0112, November 19, 2020, online at evidencecentral.org.

- 8. Daniel David Luckenbill, Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia. Volume II. Historical Records of Assyria from Sargon to the End (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1927), 56; Ellis, Foundation Deposits in Ancient Mesopotamia, 101–103. 194; Pearce, “Materials of Writing and Materiality of Knowledge,” 173–174.

- 9. Luckenbill, Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia. Volume II. Historical Records of Assyria from Sargon to the End, 58–59. See also 37.

- 10. Luckenbill, Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia, 248. See also 254–255.

- 11. C J. Gadd, “Babylonian Foundation Texts,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 4 (October 1926): 679–688.

- 12. Ellis, Foundation Deposits in Ancient Mesopotamia, 104, 195.

- 13. Pearce, “Materials of Writing and Materiality of Knowledge,” 174.

- 14. Ellis, Foundation Deposits in Ancient Mesopotamia, 107.

- 15. Christina Tsouparopoulou, “Hidden Messages Under the Temple: Foundation Deposits and the Restricted Presence of Writing in 3rd Millennium BCE Mesopotamia,” in Verborgen, Unsichtbar, Unlesbar – Zur Problematik Restringierter Schriftprasenz, ed. Tobias Frese, Wilfried E. Keil, Kristina Kruger (Berlin and Boston, MA: De Gruyter, 2014), 28.

- 16. See also, Evidence Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Ancient Records Hidden in Boxes,” Evidence# 0112, November 19, 2020, online at evidencecentral.org.