Evidence #316 | March 1, 2022

Book of Mormon Evidence: Egyptian Metal Plates

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

Abstract

Historical documents indicate that many ancient Egyptian texts were inscribed onto plates of gold, silver, brass, and bronze. Yet relatively few of these plates have survived into modern times.Book of Mormon

The tradition of keeping sacred records on metal plates by the people of Nephi resonates in many ways with the practice of writing on metal in other cultures in the past. Readers of the Book of Mormon may wonder why comparatively few examples from Lehi’s day have survived to the present. Historical texts from ancient Egypt provide a valuable perspective on this question as it relates to the Book of Mormon, especially because the Book of Mormon was written in an Egyptian script.1

Records on Metal Plates Mentioned in Egyptian Texts

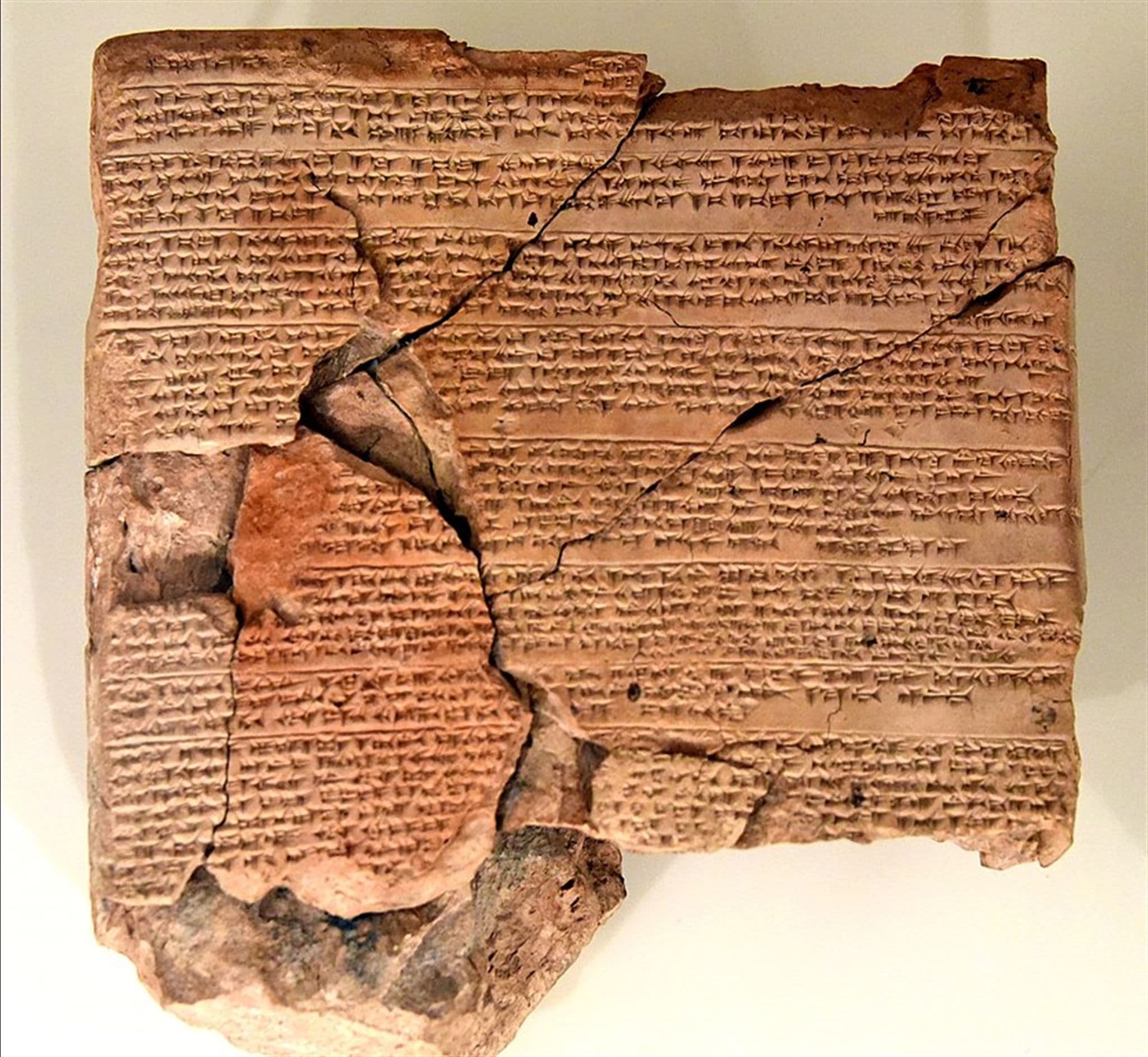

Egyptian texts refer to a variety of inscriptions on tablets of gold, silver, and brass, although little archaeological evidence for these metallic documents has survived into modern times.

Treaties

A thirteenth century treaty between Egypt and the Hittite kingdoms was made between Ramesses II and Hattusilis (circa 1280 BC). Two copies of the treaty were originally inscribed on silver tablets which were presented to each king to memorialize the agreement. These are now lost.2 The contents of this treaty are now only known from Egyptian and Hittite versions which were inscribed on stone and clay.3 The text of the treaty reviews the former hostile relations between the two kingdoms and the agreement to establish peace, an agreement for each to come to the defense of the other, extradition of refugees, divine witnesses of the treaty, and a stipulation of blessings and curses associated with compliance with the conditions set forth.4

Hymns

Egyptian texts from the New Kingdom period also refer to hymn-related inscriptions on tablets of gold, silver, and brass. The temple of Karnak contains a hymn to the god Amon which it says was originally inscribed on “a tablet of silver.”5 In a study of the text, Keith Seele observed that the silver tablet and other inscriptions on precious metal “have gone the way of most of the treasures of antiquity, having become ages ago a part of the loot of those pillagers whose unremitting activities have robbed us of most of the records and works of art in the ancient world.”6

Votive Offerings, Temple Records, and Rituals

The military campaigns of Ramesses, Merneptah, and Ramesses III brought tremendous treasure to Egypt, much of which was dedicated to the gods of Egyptian temples. According to T. Eric Peet, “The Great Harris Papyrus, drawn up by Ramesses IV to record his father’s benefactions to the temples of the land, gives an impressive idea of the wealth of which the temple and priesthood of Amun were possessed.”7 The text reads:

I made for thee great inscriptions of beaten gold, cut in the great name of Thy Majesty having my adorations. I made for thee other inscriptions of beaten silver in the name of Thy Majesty on the tablet of the temple. I made for thee great plates of beaten silver cut in the name of Thy Majesty engraved with the chisel having tablets and registers of the temples which I made in TA-MERA during my reign on earth to perpetuate thy name for ever and ever and ever, thou art their guide in responding face to face. I made for thee other plates of beaten brass, they were six-sided of the colour of gold, cut and engraved by the chisel in the great name of Thy Majesty with lists of the sanctuaries and of the temples also the numerous praises and adorations I made to thy name, thou wast pleased to hear them Oh Lord of the gods!8

None of these inscriptions on metal tablets have survived. Other Egyptian inscriptions indicate that some temple rituals were inscribed on metal. An inscription from the temple of Edfu refers to a ritual to be read from a tablet of silver, and at the Dendera similar tablets of silver and gold were also to be read during temple rituals.9

One of these is a bronze hieroglyphic inscription on a bronze plate from Pharaoh Necho II, which dates to the time of Lehi (610–595 BC).10 Additional inscriptions were discovered on the fragmentary remains of two bronze plates dating centuries later to the Roman period in Egypt (30 BC—AD 14), found at the Temple of Hathor at Dendera.11 The plates (BM 57371 and BM 57372) were votive or dedicatory offerings inscribed to be a permanent record of the donor’s generosity to the temple and piety. Both tablets were inscribed on both sides, one in hieroglyphic and the other in demotic, but the text is only partially readable. One of the plates (BM 57371) was damaged by fire, apparently in an attempt to melt it down.12

Rarity of Egyptian Archaeological Examples

When we compare references to plates found in Egyptian texts with the archaeological record, we are struck by the dearth of evidence from ancient Egypt. Addressing this problem, A. F. Shore observes, “The value of all metal during the ancient period virtually excludes the survival of such records except in the most fortuitous circumstances. The practice would certainly have been more common than the surviving material would suggest.”13

In light of the tragic loss of the tablets of gold, silver, and brass mentioned in the Great Harris Papyrus, it is not difficult to imagine what would have happened to Laban’s plates of brass had they remained in his treasury when Jerusalem was destroyed (2 Kings 24:13; 25:13–17; Jeremiah 20:5). It is noteworthy that one of the few fragmentary examples of metal plates that has survived is one that dates to the time of Lehi.

Commentating on the Dendera tablets, Shore observes “Since the two tablets are inscribed on both sides they can hardly have been intended for display in the temple of Dendera … the most likely place for them to have been kept would have been in the temple treasury or magazine and to have been found with the hoard or hoards of ritual and votive objects enumerated here.”14 These examples of double-sided plates lend support to the idea that records on metal may have served a purpose beyond their value as temple treasure and could potentially have been used for consultation by temple priests or scribes if the need arose, as was the case in other cultures where temple records were inscribed on metal.15

Conclusion

The disparity between references to records on metal plates in Egyptian texts and surviving examples of such documents illustrates how a prominent form of literary expression can be poorly represented in the archaeological record of a culture. Had no references to metal plates been preserved (typically on other records of papyri or stone), most scholars would long have assumed that the Egyptian practice of recording inscriptions on metal tablets was nearly non-existent.

In spite of their rarity, the limited and fragmented archaeological examples of metal records, coupled with literary references to the same, indicate that in ancient Egypt metal records included important international texts such as treaties, votive offerings to Egyptian temples, hymns of praise and adoration to deities, ritual temple texts, and registers of temple donations. Archaeological evidence also shows that some of these documents were inscribed on both sides (like the Book of Mormon plates), suggesting that they were not simply ornamental objects posted on a wall but could have been consulted when deemed necessary.

While not all of these genres are present in the Book of Mormon, there are some meaningful connections. For instance, the Savior’s request that records be brought forth when he visited the temple at Bountiful suggests that records of a religious or liturgical nature may have been kept somewhere in the temple precincts (3 Nephi 23:6–14). Treaties are mentioned on several occasions (Mosiah 9:6–7; 19:15; Mormon 2:28–29), as well as several examples of hymns of praise, including prayers to God (1 Nephi 1:14; 2 Nephi 4:15–35; Mosiah 8:20–21; Alma 29:1–17; 31:26–35; 33:4–11; 33:16; 3 Nephi 4:29–32)—all of which were eventually recorded on the metal plates of the Book of Mormon. This evidence is consistent with the ancient Near Eastern background of the Book of Mormon.

Book of Mormon Central, “Are There Other Ancient Records Like the Book of Mormon? (Mormon 8:16),” KnoWhy 407 (February 13, 2018).

William J. Hamblin, “Sacred Writing on Metal Plates in the Ancient Mediterranean,” FARMS Review 19, no. 1 (2007): 37–54.

H. Curtis Wright, “Ancient Burials of Metal Documents in Stone Boxes,” in “By Study and Also By Faith”: Essays in Honor of Hugh Nibley, 2 vols., ed. John M. Lundquist and Stephen D. Ricks (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 1990), 273–334.

H. Curtis Wright, “Metallic Documents in Antiquity,” BYU Studies Quarterly, 10, no. 4 (1970): 457–477.

- 1. See Evidence Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Egyptian Writing,” Evidence# 0033, September 19, 2020, online at evidencecentral.org.

- 2. James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, Third edition with Supplement (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1969), 199, 201–202.

- 3. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, 199.

- 4. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, 199–203.

- 5. Keith C. Seele, “A Hymn to Amon-Re on a Tablet from the Temple of Karnak,” in From the Pyramids to Paul: Theology, Archaeology and Related Subjects Prepared in Honor of the Seventieth Birthday of George Livingston Robinson, ed. Lewis Gaston Leary (New York, NY: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1935), 232.

- 6. Seele, “A Hymn to Amon-Re on a Tablet from the Temple of Karnak,” 224.

- 7. T. Eric Peet, The Great Tomb Robberies of the Twentieth Egyptian Dynasty (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1930), 6.

- 8. August Eisenlohr and S. Birch, “Annals of Rameses III,” in Records of the Past: Being English Translations of the Assyrian and Egyptian Monuments. Volume VI. Egyptian Texts, ed. A. H. Sayce (London: Samuel Bagster and Sons, 1892), 29. August Eisenlohr and S. Birch, “Annals of Rameses III,” 29–30. Eisenlohr and Birch’s translation somewhat confusingly characterizes these brass plates “as six sided.” A more accurate translation would be “six-fold alloy,” meaning referring to the content of the brass plates rather than their shape. See Pierre Grandet, Le Papyrus Harris I. 2 vols (Le Caire: Institut francais d’ archeologie orientale du Caire, 2005), 2:28–32.

- 9. Seele, “A Hymn to Amon-Re on a Tablet from the Temple of Karnak,” 226; A.F. Shore, “Votive Objects from Dendera of the Graeco-Roman Period,” in Glimpses of Ancient Egypt. Studies in Honour of H. W. Fairman, ed. John Ruffle, G.A. Gaballa, Kenneth A. Kitchen (Warminster, Eng.: Aris and Phillips, 1979), 158.

- 10. Susanne Bickel, In ägyptischer Gesellschaft: Aegyptiaca der Sammlungen Bibel + Orient an der Universität Freiburg (Fribourg: Academic Press, 2004), 42.

- 11. A.F. Shore, “Votive Objects from Dendera of the Graeco-Roman Period,” 141–158; Richard Parkinson, Cracking Codes: The Rosetta Stone and Decipherment (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1999), 147.

- 12. Parkinson, Cracking Codes: The Rosetta Stone and Decipherment, 147.

- 13. Shore, “Votive Objects from Dendera of the Graeco-Roman Period,” 158.

- 14. Shore, “Votive Objects from Dendera of the Graeco-Roman Period,” 158.

- 15. Examples of sets of metal plates with inscriptions on both sides include the bronze Iguvine Tablets from Italy, Buddhist bronze plates from Japan, and Medieval Indian copper plate grants. The Tiruvalla Copper Plates of Kerala India are a set of forty-three plates with inscriptions on both sides which contain a record of temple donations, temple committee resolutions, and a fine imposed for violations of temple rules during the 10–11th centuries AD. This archival collection was originally housed in the Hindu temple at Tiruvalla, but are now in the custody of the Archaeological Department of Kerala. See M.G.S., Narayanan, Perumals of Kerala: Brahmin Oligarchy and Ritual Monarchy (Kerala, Indian: Cosmo Books, 2018), 473.