Evidence #34 | September 19, 2020

Book of Mormon Evidence: Zemnarihah’s Hanging

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

Abstract

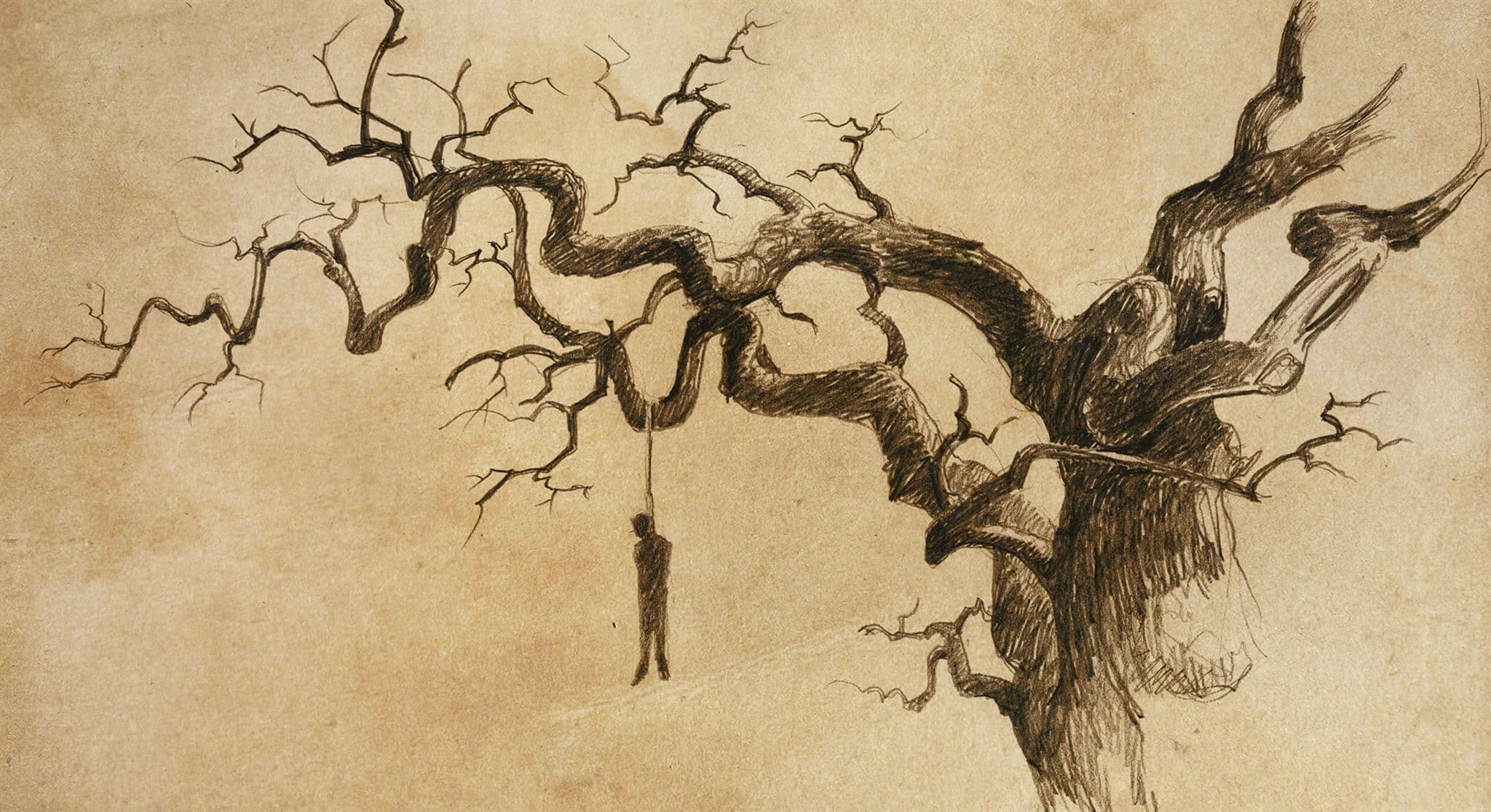

Various lines of evidence help establish that the story of Zemnarihah’s hanging is grounded in an ancient Near Eastern legal context.At the conclusion of a military conflict in 3 Nephi 4, the Nephites captured Zemnarihah, the leader of the Gadianton robbers whom they were fighting. According to the text,

Zemnarihah, was taken and hanged upon a tree, yea, even upon the top thereof until he was dead. And when they had hanged him until he was dead they did fell the tree to the earth, and did cry with a loud voice, saying: May the Lord preserve his people in righteousness and in holiness of heart, that they may cause to be felled to the earth all who shall seek to slay them because of power and secret combinations, even as this man hath been felled to the earth. (vv. 28–29)

Various lines of evidence suggest that the story of Zemnarihah’s hanging is grounded in an ancient Near Eastern legal context.

Lack of a Trial

The fact that no trial is mentioned for Zemnarihah is consistent with the way that robbers were legally perceived and dealt with in the ancient Near East. Legal scholar John W. Welch has explained, “Robbers in the ancient world were more than common thieves; they were outsiders and enemies to society itself. As such, the ancients reasoned, they were outlaws, outside the law, and not entitled to legal process. Against bandits and brigands, ‘the remedies were military, not legal.’”1

Hanging: An Ancient Israelite Tradition

In ancient Israel, the legal grounds for hanging as a form of execution come from Deuteronomy 21:22–23:

And if a man have committed a sin worthy of death, and he be to be put to death, and thou hang him on a tree: His body shall not remain all night upon the tree, but thou shalt in any wise bury him that day; (for he that is hanged is accursed of God;) that thy land be not defiled, which the Lord thy God giveth thee for an inheritance.

Welch has pointed to several examples demonstrating that, as interpreted and practiced under Israelite law, hanging “could be used either as a means of execution or as a way of displaying the body of an executed criminal.”2 There is evidence from the Dead Sea Scrolls that hanging was specifically used as a punishment for crimes of treason or dissention. This fits the case of Zemnarihah, who led a group of robbers that had dissented from the Nephites.3

Cutting Down the Tree

According to Welch, it appears that the felling of the tree upon which Zemnarihah was hanged was “done consciously in accordance with ancient legal custom. Although the practice cannot be documented as early as the time of Lehi, Jewish practice shortly after the time of Christ expressly required that the tree upon which the culprit was hung had to be buried with the body. Hence the tree had to be chopped down.”4 Although the “origins of this particular practice in Israelite legal history are obscure,” Welch suggested that its “striking similarities” with Zemnarihah’s hanging points to “a common historical base.”5

The Punishment Fits the Crime

Most ancient Near Eastern laws operated upon the principle of talionic justice. As explained by Welch, “Talionic justice achieved a sense of poetic justice, rectification of imbalance, relatedness between the nature of the wrong and the fashioning of the remedy, and appropriateness in determining the measure or degree of punishment.”6 In other words, people reaped what they sowed. “In Zemnarihah’s case, he was hung in front of the very nation he had tried to destroy, and he was felled to the earth just as he had tried to bring that nation down.”7

The People “Cried with a Loud Voice”

After Zemnarihah was hanged, the people publicly (and presumably in unison or in some sort of ritual or chant) “cried with a loud voice” (3 Nephi 4:28). Among other things, they petitioned that those who sought to slay the righteous would be “be felled to the earth … even as this man hath been felled to the earth” (v. 29; emphasis added). The public aspect of this ritual seems to be based upon Deuteronomy 19:20, which, after stipulating the punishment for sinners, states that those who “remain shall hear, and fear, and shall henceforth commit no more any such evil among you” (emphasis added). Such a display would likely help persuade all who witnessed or participated in it to not join the wicked groups of robbers who plagued the land.

Interestingly, this public statement also contains what is known as a simile curse, which uses a verbal comparison or ritual action to emphasize the nature of the curse. In this case, the curse compared the fate of the wicked to the fate of Zemnarihah. In the ancient world, such a curse, openly proclaimed by all the people in unison, would not have been taken lightly.8

John W. Welch, The Legal Cases in the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: BYU Press, 2008), 351–356.

John A. Tvedtnes, “More on the Hanging of Zemharihah,” in Pressing Forward with the Book of Mormon: The FARMS Updates of the 1990s, ed. John W. Welch and Melvin J. Thorne (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1999), 208–210.

John W. Welch, “The Execution of Zemnarihah,” in Reexploring the Book of Mormon: A Decade of New Research, ed. John W. Welch (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1992), 250–252.

- 1. John W. Welch, The Legal Cases in the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: BYU Press, 2008), 354. See also, John W. Welch, “Legal and Social Perspectives on Robbers in First-Century Judea,” BYU Studies 36, no. 3 (1996–1997): 141–153; Kent P. Jackson, “Revolutionaries in the First Century,” BYU Studies 36, no. 3 (1996–1997): 129–140; John W. Welch and Kelly Ward, “Thieves and Robbers,” in Reexploring the Book of Mormon: A Decade of New Research, ed. John W. Welch (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1992), 248–249; John W. Welch, “Theft and Robbery in the Book of Mormon and Ancient Near Eastern Law,” FARMS Preliminary Report (1985), 1–41.

- 2. Welch, Legal Cases, 351.

- 3. See John A. Tvedtnes, “More on the Hanging of Zemnarihah,” in Pressing Forward with the Book of Mormon: The FARMS Updates of the 1990s, ed. John W. Welch and Melvin J. Thorne (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1999), 208–210.

- 4. Welch, Legal Cases, 354.

- 5. Welch, Legal Cases, 354. Welch further commented, “The rationale for chopping down the tree seems to relate to the idea of removing all traces and recollections of the executed criminal from the face of the earth, as well as expunging any impurities that the dead body would have caused.” (p. 355). This corresponds to the passage in Deuteronomy, which indicates that the hanged criminal was not supposed to remain upon the tree but was to be buried because he was “accursed of God” (Deuteronomy 21:23).

- 6. Welch, Legal Cases, 338–339.

- 7. See John W. Welch, “The Execution of Zemnarihah,” in Reexploring the Book of Mormon: A Decade of New Research, ed. John W. Welch (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1992), 251–252.

- 8. See Evidence Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Simile Curses,” Evidence 0040, September 19, 2020, online at evidencecentral.org. See also, Donald W. Parry, “Hebraisms and Other Ancient Peculiarities in the Book of Mormon,” in Echoes and Evidences of the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2002), 156–159; John A. Tvedtnes, “As a Garment in a Hot Furnace,” in Pressing Forward with the Book of Mormon: The FARMS Updates of the 1990s, ed. John W. Welch and Melvin J. Thorne (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1999), 127–131; Mark J. Morrise, “Simile Curses in the Ancient Near East, Old Testament, and Book of Mormon,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 2, no. 1 (1993): 124–138.