473 | December 4, 2024

Book of Mormon Evidence: Sacrifices of Man, Beast, and Fowl

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

Abstract

Amulek’s mention of three types of sacrifice (man, beast, and fowl) and his refutation of vicarious human sacrifice fit well in both an ancient Near Eastern and ancient American cultural context.Three Types of Sacrifices

When teaching the poor among the Zoramites, Amulek clarified the nature of Christ’s atoning sacrifice by stating that it would not be “a sacrifice of man, neither of beast, neither of any manner of fowl; for it shall not be a human sacrifice; but it must be an infinite and eternal sacrifice” (Alma 34:10).1 This statement may be culturally significant, as both the Israelites and Nephites lived among societies that performed vicarious sacrifices.

For example, it appears that Micah, an Israelite prophet, also mentioned these three forms of sacrifice. He asked if he should “come before the Lord” with “burnt offerings [often birds], with calves of a year old?” Whether “the Lord [would] be pleased with thousands of rams” or if he should “give my firstborn for my transgression, the fruit of my body for the sin of my soul?” In answer, the Lord only required him “to do justly, and to love mercy, and to walk humbly with thy God” (Micah 6:6–8).

Assuming the “burnt offerings” mentioned by Micah were birds (see Leviticus 1:14), he presents a sequence of (1) fowl, (2) beast, (3) man.2 Interestingly, Amulek’s wording provides a reversal of this order, stressing that Christ’s atonement would not be a sacrifice of (3) man, (2) beast, or (1) fowl (Alma 34:10). If intentional, this may be an example of what scholars refer to as Seidel’s Law, in which Hebrew authors inverted the statements of past writers when quoting or paraphrasing them.3

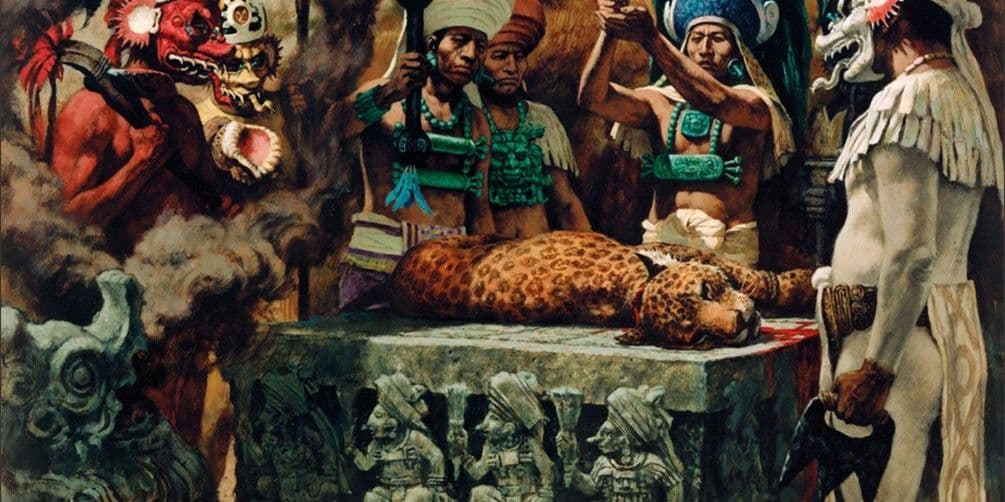

Yet Amulek’s statement would also have fit well in an ancient American setting. As pointed out by Brant Gardner, “Mesoamerican culture … offered parallel examples of animal sacrifices as part of their worship and even human sacrifice.”4 Mark Wright explains,

The peoples of the Book of Mormon would have been familiar with the types of sacrifices being offered by their surrounding Mesoamerican neighbors, which often comprised burnt offerings of animals, such as deer or birds. The righteous would have interpreted such sacrifices as a means to point their souls to Christ (Jacob 4:5; Alma 34:14). Yet Amulek prophesied that “it is expedient that there should be a great and last sacrifice; yea, not a sacrifice of man, neither of beast, neither of any manner of fowl; for it shall not be a human sacrifice; but it must be an infinite and eternal sacrifice” (Alma 34:10). It is significant that the three things that Amulek is expressly telling the apostate Zoramites not to sacrifice are the three most common things that were offered by Mesoamerican worshipers: human, beast, and fowl. It stands to reason that the Zoramites, in rejecting Nephite religion, would embrace the cultural practices of the more dominant culture, as would be expected of an apostate group.5

Vicarious Human Punishment or Sacrifice

After mentioning the types of sacrifices that could not provide atonement for sins, Amulek further explained: “Now there is not any man that can sacrifice his own blood which will atone for the sins of another. Now, if a man murdereth, behold will our law, which is just, take the life of his brother? I say unto you, Nay. But the law requireth the life of him who hath murdered; therefore there can be nothing which is short of an infinite atonement which will suffice for the sins of the world” (Amulek 34:11–12).

Once again, Amulek’s statement is congruent with Israelite law, which did not allow for the vicarious punishment or sacrifice but insisted “every man shall be put to death for his own sin” (Deuteronomy 24:16; cf. Ezekiel 18:20).6 In contrast, Jewish Studies lecturer Elaine Goodfriend explains, “Vicarious punishment—when the penalty for a wrong is suffered by someone other than the perpetrator—is found in” some Mesopotamian laws.7 Ze’ev Falk notes, “in Babylonian and perhaps also in Hittite law, the principle of talion was applied not only to the criminal himself but also to his dependents.”8

A similar conception of vicarious sacrifice or punishment was present in ancient Mesoamerica.9 In that context, “Maya kings voluntarily shed their blood as an offering on behalf of their people.”10 This came in the form of bloodletting, a practice where the king “used thorns, stingray spines, and obsidian blades to draw blood from” sensitive parts of the body.11

While this is a different conceptual background than that of the Babylonian laws in the Old World, it was indeed a system wherein a man could vicariously “sacrifice his own blood” for his people—precisely what Amulek was preaching against (Amulek 34:11). As proposed by Gardner, “Amulek says ‘sacrifice his own blood’ because the king’s letting of some of his own blood was ‘the mortar of ancient Maya ritual life.’”12

Conclusion

On various levels, Amulek’s discussion of sacrifices fits well in both an ancient Near Eastern and ancient American context. His statements are congruent with Israelite law and may draw upon the teachings of the Israelite prophet Micah. Yet they also fit exceptionally well in an ancient Mesoamerican context, where various animal and human sacrifices were prevalent and where human blood was indeed believed to have vicarious atoning power.13 Together, these combined cultural, legal, and textual parallels help support the Book of Mormon’s antiquity and miraculous translation.

Mark Alan Wright and Brant A. Gardner, “The Cultural Context of Nephite Apostasy,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 1 (2012): 25–55.

Mark Alan Wright, “Axes Mundi: Ritual Complexes in Mesoamerica and the Book of Mormon,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 46 (2021): 233–248.

Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 4:477–478.

- 1. See Mark Alan Wright and Brant A. Gardner, “The Cultural Context of Nephite Apostasy,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 1 (2012): 52: “Perhaps we are seeing clues to the process of apostasy when Amulek is teaching Zoramite outcasts and specifically defines Christ’s sacrifice by what it was not.”

- 2. Since other animals besides birds were also offered as burnt offerings, the interpretation of birds in this passage must remain tentative. See Leviticus 1:10.

- 3. See Scripture Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Inverted Quotations,” Evidence 440 (March 12, 2024).

- 4. Gardner, Second Witness, 4:477, typo silently corrected.

- 5. Mark Alan Wright, “Axes Mundi: Ritual Complexes in Mesoamerica and the Book of Mormon,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 46 (2021): 240.

- 6. Ze’ev W. Falk, Hebrew Law in Biblical Times, 2nd ed. (Winona Lake, IN and Provo, UT: Eisenbrauns and BYU Press, 2001), 68 notes, “Hebrew courts did not inflict punishment on ascendants or descendants.” In relation to vicarious punishment, Elaine Adler Goodfriend, “Ethical Theory and Practice in the Hebrew Bible,” in The Oxford Handbook of Jewish Ethics and Morality, ed. Elliot N. Dorff and Jonathan K. Crane (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2013), 48 n.9, notes, “Exod 21:31 and Deut 24:16 prohibit this practice.”

- 7. Goodfriend, “Ethical Theory and Practice in the Hebrew Bible,” 48 n.9. Goodfriend specifically cites “the Laws of Hammurabi 230 and 210, and Middle Assyrian Law A55.”

- 8. Falk, Hebrew Law in Biblical Times, 68. Talion is the “eye for an eye” concept, or in the case of murder, a life for a life. For a comprehensive study of talionic justice in the Book of Mormon, see Scripture Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Talionic Justice,” Evidence 198 (May 27, 2021).

- 9. See Scripture Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Auto-Sacrifice,” Evidence 238 (September 12, 2021).

- 10. Wright and Gardner, “The Cultural Context of Nephite Apostasy,” 51.

- 11. Wright and Gardner, “The Cultural Context of Nephite Apostasy,” 51.

- 12. Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 4:478.

- 13. For several recent studies on animal and human sacrifice in ancient Mesoamerican, see Rubén G. Mendoza and Linda Hansen, eds. Ritual Human Sacrifice in Mesoamerica: Recent Findings and New Perspectives (Springer, 2024); Sarah E. Newman and Franco D. Rossi, “Animal Sacrifice in Mesoamerica,” in Substance of the Ancient Maya: Kingdoms and Communities, Objects and Beings, ed. Garrison, Thomas G., and Andrew K. Scherer (University of New Mexico Press, 2024), 243–268; Vera Tiesler and Guilhem Olivier, “Open Chests and Broken Hearts: Ritual Sequences and Meanings of Human Heart Sacrifice in Mesoamerica,” Current Anthropology 61, no. 2 (2020); Ximena Maria Chavez Balderas, The Offering of Life: Human and Animal Sacrifice at the West Plaza of the Sacred Precinct (PhD. dissertation, Tulane University, 2019); Chinchilla Mazariegos, Vera Tiesler, Oswaldo Gómez, and T. Douglas Price, “Myth, Ritual and Human Sacrifice in Early Classic Mesoamerica: Interpreting a Cremated Double Burial from Tikal, Guatemala,” Cambridge Archaeological Journal 25, no. 1 (2015): 187–210. For more on auto-sacrifice, see Scripture Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Auto-Sacrifice,” Evidence 238 (September 12, 2021).