Evidence #112 | November 19, 2020

Book of Mormon Evidence: Records Hidden in Boxes

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

Abstract

Joseph Smith claimed that the Book of Mormon and other Nephite artifacts were deposited a stone box. There is ample archaeological and historical precedent for hiding documents and other relics in boxes.Nephite Artifacts Discovered in a Stone Box

In his account of finding the plates of the Book of Mormon, Joseph Smith described them as having been placed in a stone box along with other Nephite artifacts:

Convenient to the village of Manchester, Ontario county, New York, stands a hill of considerable size, and the most elevated of any in the neighborhood. On the west side of this hill, not far from the top, under a stone of considerable size, lay the plates, deposited in a stone box. … The box in which they lay was formed by laying stones together in some kind of cement. In the bottom of the box were laid two stones crossways of the box, and on these stones lay the plates and the other things with them. (Joseph Smith—History 1:51–51)

Records Discovered in Boxes in the Ancient Near East

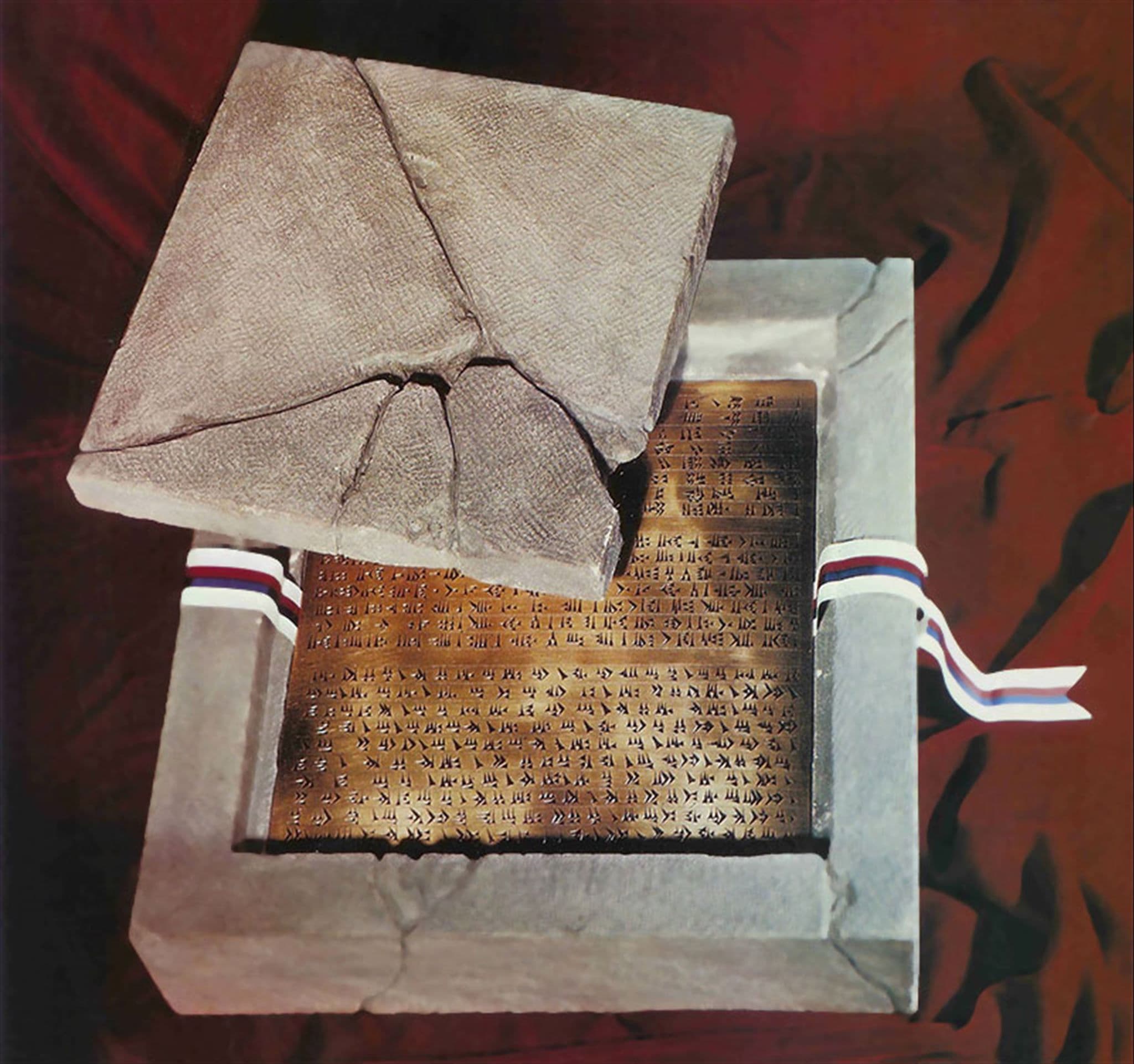

H. Curtis Wright has drawn attention to the nearly 3000-year-long practice of placing various types of engraved metal texts in box-like receptacles and then secreting them in the foundations, walls, or other inaccessible recesses of ancient temples and palaces.1 A well-known example of such a text can be seen in the inscriptions of Darius, which were written on plates made of gold and silver. The set from Hamadan (a similar set with the same inscription was found at Persepolis) was found embedded within two square hewn stones.2 Since many of these documents were stored in the foundations of temples, it is noteworthy that the original Book of Mormon records may likewise have been kept within the precincts of Nephite temples.3

Codices Associated with Boxes in Ancient America

Moving to the New World, there is some evidence that the ancient Maya may have stored documents in various types of boxes.4 The dimensions of a stone box discovered in a Guatemalan cave, for example, seem appropriate for the storage of Maya books known as codices.5 The sides of the box depict deities interacting in various ways with codices, leading researcher to suspect that the stone container “may well have once held a codex.”6 Other discoveries of box-like receptacles, or iconographic depictions of them, suggest that some ancient Maya books were indeed “kept in ‘bespoke’ boxes … as objects of sacred meaning, to be set apart, kept apart, ritually activated, perhaps even sprinkled with incense and other offerings.”7

Reports of Ancient Records Deposited in Boxes

In addition to archaeological finds, John A. Tvedtnes has drawn attention to various ancient reports of records kept in boxes. The most prominent example is surely the Israelite Ark of the Covenant, the contents of which have numerous parallels with the those found in the stone box containing the Book of Mormon and other Nephite relics.8

Other examples come from Egyptian texts, one of which “describes how to inscribe a text on a gold or silver lamella (plate) and place it ‘in a clean box.’”9 Another Egyptian document relates that a man named Horus “slept overnight in a temple, where the god Thoth told him in a dream that he would find a box containing a book written by Thoth himself concealed in a naos [inner sanctuary] within the temple.”10 Another sample says that “Thoth’s book of magic was hidden in a gold box inside a silver box, inside an ebony and ivory box, inside a box of juniper wood, inside a copper box, inside an iron box concealed in the river at Coptos.”11

Similar accounts can be found in Jewish and Christian writings. In the Jewish text known as 3 Enoch, “we read that the angel in charge of the heavenly archives keeps a scroll in a sealed box. The box is to be opened and the scroll is to be read in the heavenly court” (see 3 Enoch 27:1–2).12 According to Pirqe Rabbi Eliezer 50, the “records of the Persian king were placed ‘in the king’s box,’ whence they could be retrieved and read when necessary.”13 At the conclusion of the of the Apocalypse of Peter (Ethiopic version), Peter tells Clement about the transfiguration and instructs him to “hide the revelation in a box.”14 And, as a final sample, the preface to the Apocalypse of Paul reports that “the document was discovered during the fourth century in a stone box buried beneath a house in Tarsus, when a young man followed the instructions of an angel and searched for it.”15

Conclusion

Many more archaeological and historical examples could be cited, but these samples demonstrate that the notion of hiding records (including metal records) in various types of boxes was widespread in the ancient world. These findings lend plausibility to Joseph Smith’s claim of having discovered a set of ancient artifacts, including an engraved metal record, in a stone box.

John A. Tvedtnes, “Hiding Records in Boxes,” in The Book of Mormon and Other Hidden Books: “Out of Darkness Unto Light” (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2000), 31–57.

H. Curtis Wright, “Ancient Burials of Metal Documents in Stone Boxes,” in By Study and Also By Faith: Essays in Honor of Hugh W. Nibley, Volume 2, ed. John M. Lundquist and Stephen D. Ricks (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1990), 273–334; republished as H. Curtis Wright, Ancient Burials of Metallic Foundation Documents in Stone Boxes, Occasional Papers 157 (Urbana-Champaign, IL: University of Illinois, 1993).

Joseph Smith—History 1:51–51

- 1. See H. Curtis Wright, “Ancient Burials of Metal Documents in Stone Boxes,” in By Study and Also By Faith: Essays in Honor of Hugh W. Nibley, Volume 2, ed. John M. Lundquist and Stephen D. Ricks (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1990), 273–334; republished as H. Curtis Wright, Ancient Burials of Metallic Foundation Documents in Stone Boxes, Occasional Papers 157 (Urbana-Champaign, IL: University of Illinois, 1993). Based on the available archaeological data, this practice seems to have begun in Mesopotamia during the Early Dynastic period (ca. 2700–2500 BC). According to Wright, “The metallic foundation tradition, though frequently interrupted, lived on until the crash of the Late Assyrian Empire (ca. 626–609 B.C.), when it perished because the NeoBabylonians instituted other documentary procedures. It was briefly resurrected from the Late Assyrian period by the Achaemenid dynasty of Persia (539–331 B.C.), only to die once more, at least to all appearances, when Alexander the Great fired the palace at Persepolis. But the metallic foundation inscription surfaced yet again at Alexandria in the excavations of (1) a granite box for holding the writings of a late Greek author, and (2) dozens of small metallic plates from the foundations of the Serapis Temple, which housed the Serapeum Library.” (pp. 282–283)

- 2. See Wright, “Ancient Burials of Metal Documents in Stone Boxes,” 280–281.

- 3. See Don Bradley, The Lost 116 Pages: Reconstructing the Book of Mormon’s Missing Stories (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2019), 4–8, 200–208; Don Bradley, “American Proto-Zionism and the ‘Book of Lehi’: Recontextualizing the Rise of Mormonism,” (M.A. Thesis, Utah State University, 2018), 89–95, 128–133; Don Bradley, “Piercing the Veil: Temple Worship in the Lost 116 Pages,” FairMormon presentation, 2012, online at archive.bookofmormoncentral.org. See also Evidence Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: The Nephite Ark,” November 18, 2020, online at evidencecentral.org.

- 4. Allen Christensen has drawn attention to the “rather common practice among the ancient Maya to periodically demolish their pyramid temples and build over them …. Beneath the floors of each successive structure the Maya placed caches or elite burials containing precious objects from the previous phase to ensure the continuation of [the] temple’s efficacy according to sacred precedent.” Allen J. Christenson, “Art and Society in a Highland Maya Community: The Altarpiece of Santiago Atitlán (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2001), 50. Possibly connected with this practice, four identical stone boxes containing such objects were discovered in each corner of the foundation of a church in Santiago Atitlan, which was constructed in 1570. Christenson, “Art and Society in a Highland Maya Community,” 50–51. Although these boxes didn’t contain documents, they are similar in concept to the foundation deposits from the ancient Near East (as discussed in the previous section).

- 5. See Evidence Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Codices in Stone Boxes,” September 19, 2020, online at evidencecentral.org.

- 6. Brent K. S. Woodfill, Stanley Guenter, and Mirza Monterrosa, “Changing Patterns of Ritual Activity in an Unlooted Cave in Central Guatemala” in Latin American Antiquity 23, no. 1 (March 2012), 107. See also Stephen Houston, Charles Golden, and Andrew Scherer, “Information Storage & the Classic Maya” in the blog Maya Decipherment, May 19, 2017, online at mayadecipherment.com.

- 7. Houston, Golden, and Scherer, “Information Storage & the Classic Maya,” online at mayadecipherment.com.

- 8. See Evidence Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: The Nephite Ark,” November 18, 2020, online at evidencecentral.org; John A. Tvedtnes, “Hiding Records in Boxes,” in The Book of Mormon and Other Hidden Books: “Out of Darkness Unto Light” (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2000), 33–35.

- 9. Tvedtnes, “Hiding Records in Boxes,” 36.

- 10. Tvedtnes, “Hiding Records in Boxes,” 36–37.

- 11. Tvedtnes, “Hiding Records in Boxes,” 37.

- 12. Tvedtnes, “Hiding Records in Boxes,” 36.

- 13. Tvedtnes, “Hiding Records in Boxes,” 36.

- 14. Tvedtnes, “Hiding Records in Boxes,” 36.

- 15. Tvedtnes, “Hiding Records in Boxes,” 39. See also Tvedtnes, “Appendix 1: The Book of Mormon and the Apocalypse of Paul,” in The Book of Mormon and Other Hidden Books, 183–194.