Evidence #35 | September 19, 2020

Book of Mormon Evidence: Olmec Iron

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

Abstract

The Book of Mormon describes the Jaredites digging iron ore out of the ground and working it (ca. 1100 BC). Archaeology has shown that during the same general time period, the Olmec civilization was digging iron ore out of the ground, transporting it, and shaping it in specialized workshops.Ether 10:23 describes Jaredite metal working ca. 1100 BC. No blast furnaces or smelting operations are mentioned in the text. It appears that, at this time, the Jaredites simply dug naturally-occurring high-grade ores right “out of the earth” and worked the ores as lumps of material to fashion useful objects. One of the metallic ores they dug up and worked was iron.

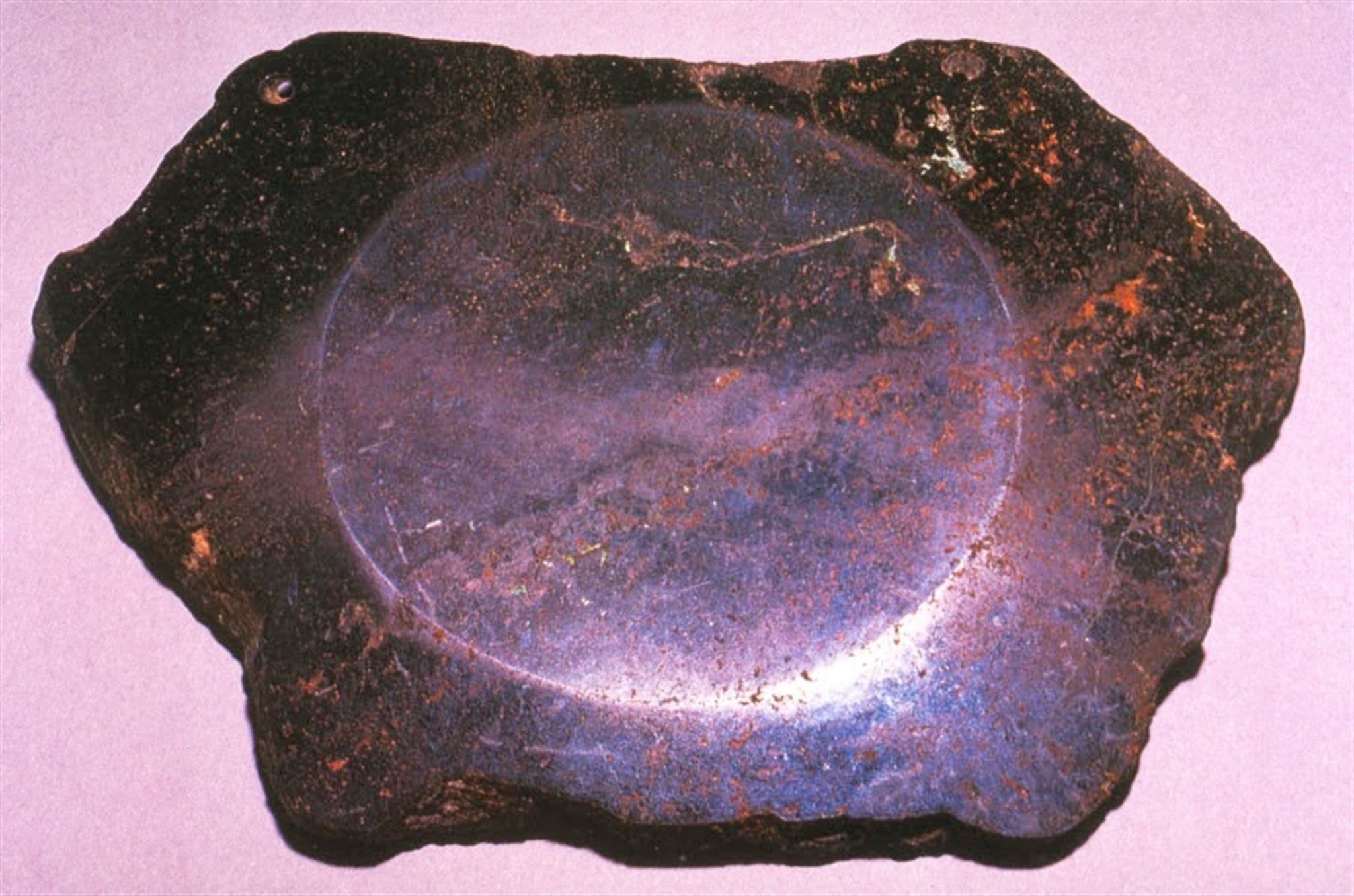

High grade meteoric iron (iron from fallen meteors) is rare, but other high-grade iron ores such as hematite, magnetite, and ilmenite are more abundant and are mined commercially today. It is widely-known among archaeologists that the Olmec fashioned polished concave iron mirrors out of naturally-occurring hematite, magnetite, and ilmenite.1

Both of the mirrors displayed above are dated prior to 400 BC, the traditional date of the Olmec collapse. A particularly impressive Olmec piece is now in the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, CT. It is a figurine of a seated dwarf fashioned from a single lump of highly polished hematite iron-ore.

Shops that worked another form of iron ore (ilmenite, a principal source of modern titanium) at an industrial scale have been discovered at three sites in southern Mesoamerica: San Lorenzo in Veracruz, and Mirador Plumajillo and Amatal, both in Chiapas. The ilmenite ore these workshops processed was imported from igneous sources in Oaxaca and Chiapas.

San Lorenzo was the first Olmec capital. Ann Cyphers Guillén found 8 tons of polished, perforated ilmenite iron-ore beads at a workshop in the SE sector of the San Lorenzo plateau. The workshop dated to ca. 1100 BC.2

The perforations were made with a drill, likely using fine sand as an abrasive. Several of the San Lorenzo artifacts were analyzed by physicists and geologists.3 The iron-ore pieces could have been used as jewelry, chain mail armor, or miniature tools when hafted with a small wooden handle. Beads average 3 centimeters in length. They are very similar in form to decorative jade beads found throughout Mesoamerica.

Jerry D. Grover, Jr., “The Swords of Shule,” in The Swords of Shule: Jaredite Land Northward Chronology, Geography, and Culture in Mesoamerica (Provo, UT: Challex Scientific Publishing, 2018), 267–281.

John L. Sorenson, Mormon’s Codex: An Ancient American Book (Provo and Salt Lake City, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship and Deseret Book, 2013), 331–344.

Steven E. Jones, Samuel T. Jones, and David E. Jones, “Archaeometry Applied to Olmec Iron-ore Beads” in BYU Studies Quarterly 37, no. 4 (1997): 129–142.

- 1. See John B. Carlson, “Olmec Concave Iron-Ore Mirrors: The Aesthetics of a Lithic Technology and the Lord of the Mirror” in The Olmec and Their Neighbors: Essays in Memory of Matthew W. Stirling, ed. Matthew W. Stirling, Michael D. Coe, Elizabeth P. Benson, and David C. Grove (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks, 1981). Matthew Stirling discovered polished hematite mirrors at La Venta in the 1940s.

- 2. See Ann Cyphers Guillén, “San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán” in Los Olmecas en Mesoamérica, ed. John E. Clark (Mexico City: Citibank/Mexico, 1994), 43–67.

- 3. Steven E. Jones, Samuel T. Jones, and David E. Jones, “Archaeometry Applied to Olmec Iron-ore Beads” BYU Studies Quarterly 37, no. 4 (1997): 129–142.