Evidence #56 | September 19, 2020

Book of Mormon Evidence: Mosiah’s Coronation

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

Abstract

The account of Mosiah’s ascension to the throne reflects prominent themes and motifs found in ancient coronation ceremonies, as attested in Israel and other Near Eastern societies.In Mosiah 1:9–10, King Benjamin asked his people to gather together so that he could publically appoint his son Mosiah to be the next king. In his study of this topic, Stephen D. Ricks found that Mosiah’s ascension to the throne has several striking parallels with ancient Near Eastern coronation ceremonies.

The Sanctuary as the Site of the Coronation

According to Ricks, “A society’s most sacred spot is the location where the holy act of royal coronation takes place.”1 Just as ancient Israelite coronations took place at the temple or at the location where the Ark of the Covenant resided,2 Mosiah’s coronation took place in a temple context (see Mosiah 1:18; 2:1, 5–7). In addition, ancient coronation ceremonies were typically divided into two parts—the anointing and the enthronement. Similarly, “Mosiah was first designated king in a private setting, presumably at the royal palace (see Mosiah 1:9–12), and then presented to the people in the public gathering at the temple (see Mosiah 2:30).”3

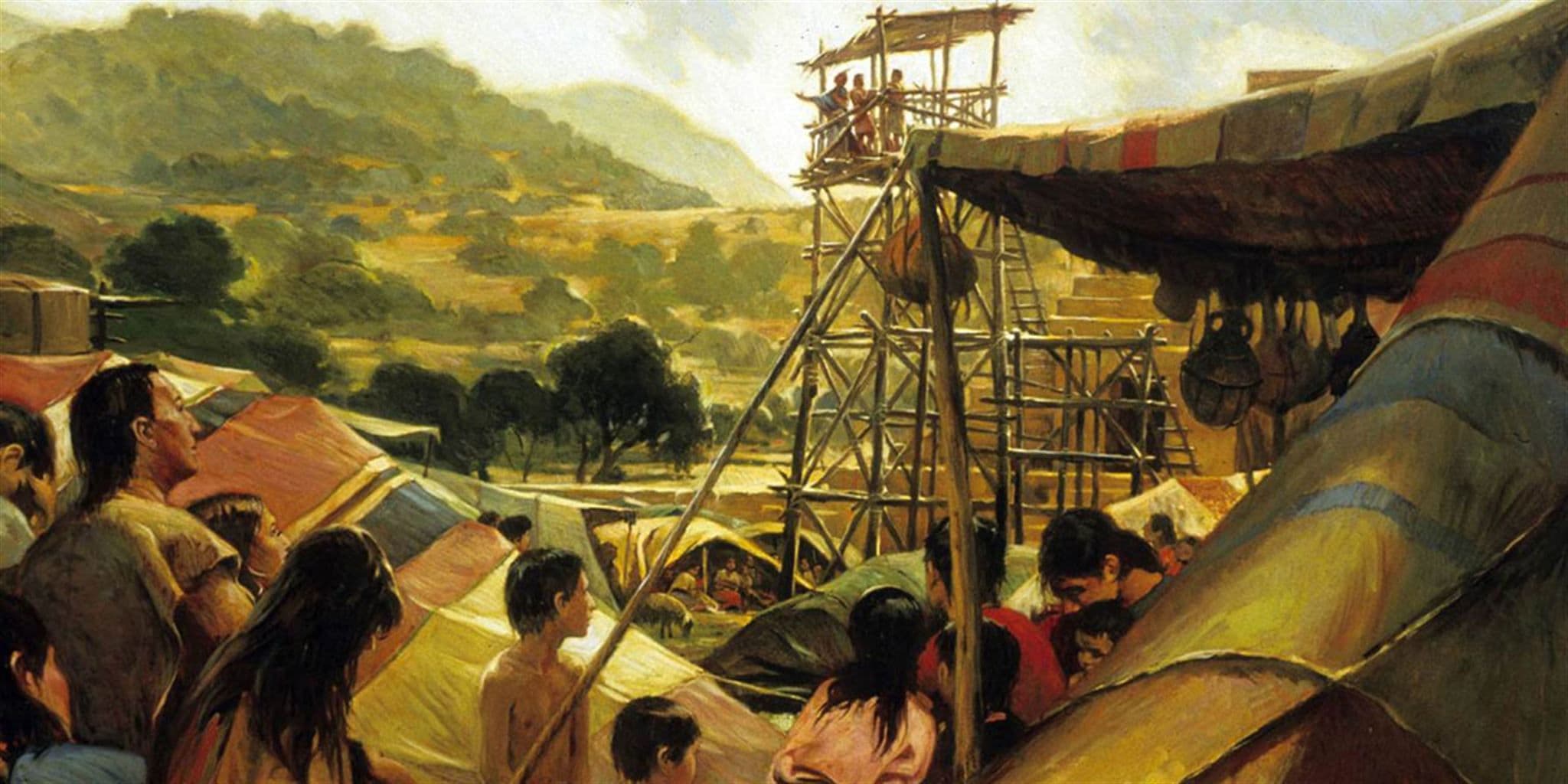

The Royal Dais

On important occasions, ancient kings often addressed their people from a raised platform, pillar, or dais. Evidence for this practice can be found in the Bible and later Jewish commentaries.4 After highlighting a number of examples, Ricks noted that together they

illustrate that platforms are (1) located in the temple precinct, (2) associated with the coronation of new kings, (3) used by the king or another leader to read the law to the people, (4) used to offer dedicatory prayers for the temple, and (5) associated with the Festival of Booths. In view of these considerations, one can conclude that Benjamin’s tower was more than just a way to communicate to the people—it was part of an Israelite coronation tradition in which the king stands on a platform or pillar at the temple before the people and before God.5

Installing in Office with Insignia

Ancient coronation ceremonies often included the bestowal of symbolic emblems or insignia upon the new king, which in various contexts included such items as a diadem (crown), a record of the law, a sword, a round ball, sacral garments, the breastplate of judgment, and the Urim and Thummim.6 The Book of Mormon indicates that King Benjamin passed on similar objects to Mosiah, including the law and other sacred writings recorded on the Brass Plates, the sword of Laban, the Liahona (see Mosiah 1:15–17) and, apparently, the Nephite interpreters (see Mosiah 28:13–14).7

Anointing

Ricks noted that to “anoint the king with oil was a significant part of coronation ceremonies in ancient Israel and in the ancient Near East generally.”8 In the Book of Mormon, the word anoint is typically used in reference to the setting apart of kings.9 While the account in the book of Mosiah doesn’t specifically mention that Mosiah was anointed with oil, it does mention that King Benjamin “consecrated his son Mosiah to be a ruler and a king over his people” (Mosiah 6:3). Ricks commented,

The verb to consecrate (from the root *QDS) is restricted to priests in the Old Testament. The two terms are similar but not identical in meaning. To anoint means to set apart by applying oil to the body, specifically the head, and to consecrate, a more general term, means to make holy. Consecrating could be done by anointing, but is not limited to it. It is possible that the consecration of Mosiah included anointing, which would have been in accordance with the practices in ancient Israel and the ancient Near East.

Presentation of the New King

Ricks proposed that, in agreement with ancient Near Eastern precedents, King Benjamin presented Mosiah to the people, at least in part, to avoid disputations or contentions about who should ascend to the throne (Mosiah 2:30–31).10 King Benjamin’s unequivocal declaration of Mosiah’s impending kingship and the people’s public acceptance (Mosiah 4:2; 5:2–4) of that declaration “follows the ancient pattern closely.”11

Receiving a Throne Name

“In many societies,” wrote Ricks, “a king received a new name or throne name when he was crowned king. Several Israelite kings had two names, a ‘birth name’ and a throne name.”12 After demonstrating several examples of this phenomenon, Ricks drew attention to the pattern set by the Nephites to call their kings “second Nephi, third Nephi, and so forth, according to the reigns of the kings; and thus they were called by the people, let them be of whatever name they would” (Jacob 1:10–11).13 Receiving a new name also plays a prominent role in King Benjamin’s speech, except in that case he broadened the ceremony to include the people at large (see Mosiah 1:12; 5:10–12).14

Divine Adoption of the King

In the ancient Near East it was commonly understood that, upon ascension to the throne, a king would be adopted as a “son” of God.15 Similarly, King Benjamin emphasized that through a sacred covenant his people “shall be called the children of Christ, his sons, and his daughters” (Mosiah 5:7). Matthew L. Bowen has proposed that when King Benjamin made this statement he was “evidently quoting the royal rebirth formula (sometimes called an adoption formula) of Psalm 2:7 ‘Thou art my Son [bĕnî ʾattâ]; this day have I begotten thee.’ Some scholars have proposed that a legal formula stands behind the phrase bĕnî ʾattâ in Psalm 2:7, pointing to similar language in Mesopotamian legal contracts.”16

Conclusion

The account of Mosiah’s ascension to the throne reflects prominent themes and motifs found in ancient coronation ceremonies, as attested in Israel and other Near Eastern societies. The way that all these details and themes show up together surrounding Mosiah’s coronation helps confirm the antiquity of that notable ceremony and, by extension, the authenticity of the Book of Mormon.

Matthew L. Bowen, “Becoming Sons and Daughters at God’s Right Hand: King Benjamin’s Rhetorical Wordplay on His Own Name,” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 21, no. 2 (2012): 2–13.

John W. Welch, “Democratizing Forces in King Benjamin’s Speech,” in Pressing Forward with the Book of Mormon, ed. John W. Welch and Melvin J. Thorne (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1999), 110–126.

Stephen D. Ricks, “Kingship, Coronation, and Covenant in Mosiah 1–6,” in King Benjamin’s Speech: “That Ye May Learn Wisdom,” ed. John W. Welch and Stephen D. Ricks (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1998), 233–276.

Stephen D. Ricks, “The Coronation of Kings,” in Reexploring the Book of Mormon: A Decade of New Research, ed. John W. Welch (Provo and Salt Lake City, UT: FARMS and Deseret Book, 1992), 124–126.

Stephen D. Ricks, “King, Coronation, and Covenant in Mosiah 1–6,” in Rediscovering the Book of Mormon: Insights You May Have Missed Before, ed. John L. Sorenson and Melvin J. Thorne (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1991), 209–219.

John W. Welch and Terry L. Szink, “Benjamin’s Tower and Old Testament Pillars,” in Pressing Forward with the Book of Mormon: The FARMS Updates of the 1990s, ed. John W. Welch and Melvin J. Thorne (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1999), 100–102.

- 1. Stephen D. Ricks, “Kingship, Coronation, and Covenant in Mosiah 1–6,” in King Benjamin’s Speech: “That Ye May Learn Wisdom”, ed. John W. Welch and Stephen D. Ricks (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1998), 233–275. See also, John W. Welch and Terry L. Szink, “Benjamin’s Tower and Old Testament Pillars,” in Pressing Forward with the Book of Mormon: The FARMS Updates of the 1990s, ed. John W. Welch and Melvin J. Thorne (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1999), 100–102.

- 2. Ricks, “Kingship, Coronation, and Covenant in Mosiah 1–6,” 244.

- 3. Ricks, “Kingship, Coronation, and Covenant in Mosiah 1–6,” 245.

- 4. Ricks, “Kingship, Coronation, and Covenant in Mosiah 1–6,” 245–247.

- 5. Ricks, “Kingship, Coronation, and Covenant in Mosiah 1–6,” 246–247.

- 6. See Ricks, “Kingship, Coronation, and Covenant in Mosiah 1–6,” 248–249.

- 7. See Ricks, “Kingship, Coronation, and Covenant in Mosiah 1–6,”248.

- 8. Ricks, “Kingship, Coronation, and Covenant in Mosiah 1–6,” 249.

- 9. The only contrary examples of this are found in 2 Nephi 20:27 and 3 Nephi 13:17, both of which are derived from the Old World texts (Isaiah 10 and Matthew 6).

- 10. See Ricks, “Kingship, Coronation, and Covenant in Mosiah 1–6,” 251.

- 11. Ricks, “Kingship, Coronation, and Covenant in Mosiah 1–6,” 252.

- 12. Ricks, “Kingship, Coronation, and Covenant in Mosiah 1–6,” 252.

- 13. Ricks, “Kingship, Coronation, and Covenant in Mosiah 1–6,” 253.

- 14. For the possible reasons that King Benjamin may have had for doing this, see Matthew L. Bowen, “Becoming Sons and Daughters at God’s Right Hand: King Benjamin’s Rhetorical Wordplay on His Own Name,” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 21, no. 2 (2012): 2–13; John W. Welch, “Democratizing Forces in King Benjamin’s Speech,” in Pressing Forward with the Book of Mormon, ed. John W. Welch and Melvin J. Thorne (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1999), 110–126.

- 15. See Ricks, “Kingship, Coronation, and Covenant in Mosiah 1–6,” 253–254.

- 16. See Bowen, “Becoming Sons and Daughters at God’s Right Hand,” 6.