Evidence #70 | September 19, 2020

Book of Mormon Evidence: Quoting Long Passages

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

Abstract

The Book of Mormon’s depiction of prophets reading lengthy scriptural texts in public settings is consistent with practices of oral discourse found anciently in Israel and other societies.Long Quotations in Public Discourse

Biblical scholar Joachim Schaper has noted that in ancient Israel, “just like in any other ancient culture,” it was common for people to read texts out loud to a gathered audience.1 One possible reason for this is that books in the ancient world were rare and expensive. Today, it is easy to print off multiple pages of text, buy a mass-market paperback, or simply read a text digitally. But in the ancient world, when scribes had to create or transcribe documents one letter at a time, access to personal copies of books was limited.2 Accordingly, “written texts … provided the basis on which literate Israelites ‘performed’ texts on significant occasions.”3

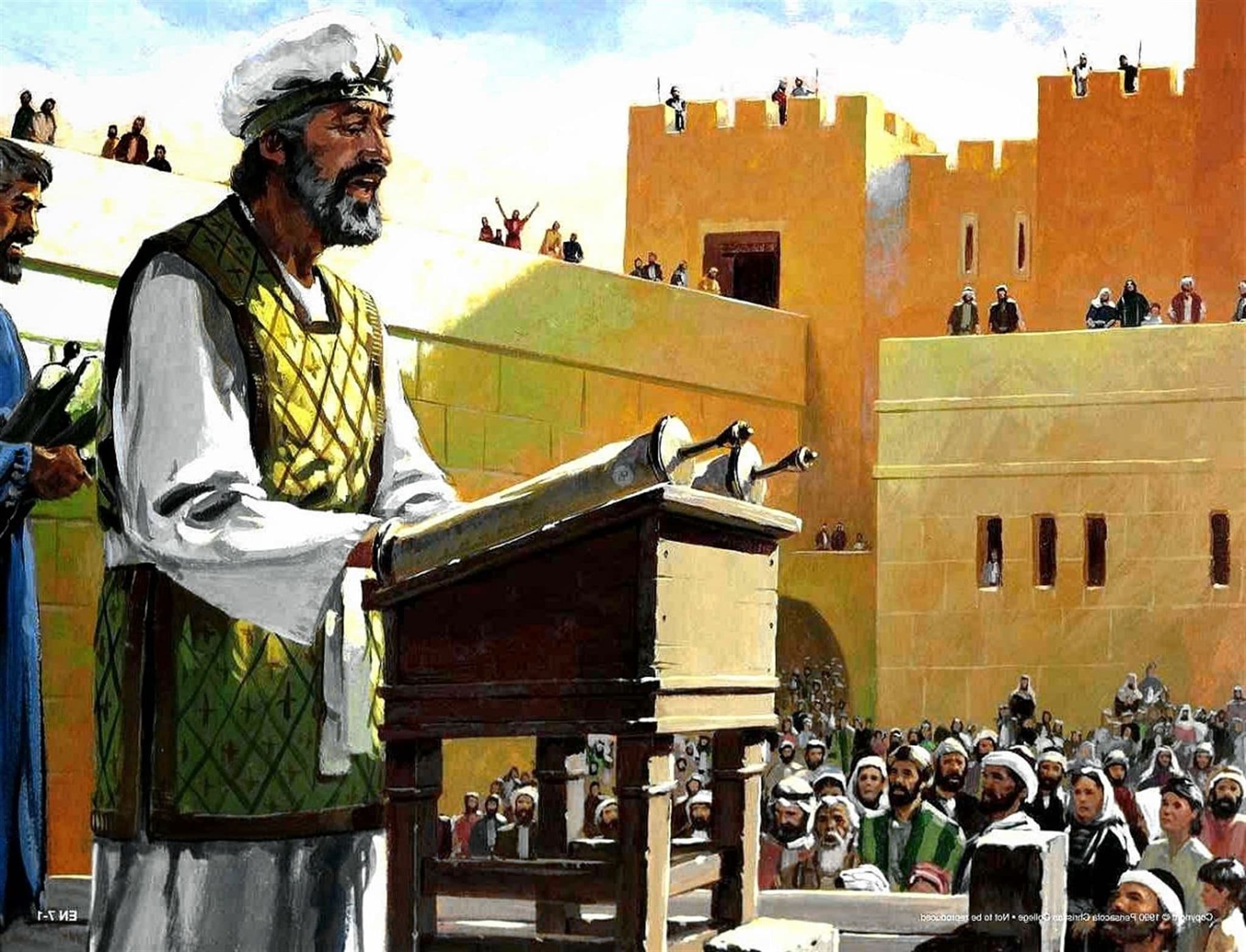

An example of a text being “performed” or read aloud in public can be seen in Nehemiah 8:1–3, which states that all the people gathered together and Ezra “read the Law of Moses to the men and the women, and those that could understand; and the ears of all the people were attentive unto the book of the law” (emphasis added).4 Deuteronomy 31:11 similarly notes that all Israel (men, women, and children) were commanded to come once every seven years to the house of the Lord to have the book of Deuteronomy “read … before all Israel in their hearing” (emphasis added).

Comparable descriptions can be found in the Book of Mormon. In some contexts a physical text was likely read aloud and in others it may have been quoted from memory. 1 Nephi 19:22 states that “Nephi ... did read many things” to his brothers “which were engraven upon the plates of brass.” Verse 23 specifies, “I did read many things unto them which were written in the books of Moses; but that I might more fully persuade them to believe in the Lord their Redeemer I did read unto them that which was written by the prophet Isaiah.” Nephi then “spake unto them, saying: Hear ye the words of the prophet, ye who are a remnant of the house of Israel, a branch who have been broken off; hear ye the words of the prophet, which were written unto all the house of Israel” (1 Nephi 19:24; emphasis added on all verses).

After quoting several chapters of Isaiah to his people, Jacob similarly declared, “And now, my beloved brethren, I have read these things that ye might know concerning the covenants of the Lord” (2 Nephi 9:1). He also quoted 77 verses from “the words of the prophet Zenos” (Jacob 5:1). During Abinadi’s trial before King Noah and his priests, Abinadi “read unto them” the Ten Commandments (Mosiah 13:11; emphasis added). He also quoted the entirety of Isaiah 53 (see Mosiah 14). And after Jesus appeared to the people at the temple in Bountiful, He quoted lengthy passages of Old World scriptures, including Mattnew 5–7 (cf. 3 Nephi 12–14), Isaiah 54 (cf. 3 Nephi 22), and Malchi 3–4 (cf. 3 Nephi 24–25).

Long Quotations in Written Texts

In a recent article, Jeff Lindsay has drawn attention to The Words of Gad the Seer—a Hebrew document of disputed authorship and origins. While some have viewed this work as deriving from medieval times, Meir Bar-Ilan, “a prominent Jewish scholar at Israel’s Meir Bar-Ilan University, named after his grandfather,” has argued for a much earlier dating.5 Interestingly, part of the evidence which he marshals for his case has to do with the insertion of long quotations of known biblical texts. Bar-Ilan writes,

The Words of Gad the Seer incorporate three chapters from the Bible as if they were part of the whole work. Chapter 10 here is Psalm 145, chapter 11 is no other than Psalm 144, and chapter 7 is a kind of compilation of 2 Sam 24:1–21 with 1 Chr 21:1–30, a chapter that deals with the deeds of Gad the Seer. As will be demonstrated later, the Biblical text in Gad’s book is slightly different from the masoretic text, with some ‘minor’ changes that might be regarded as scribal errata, though others are extremely important. In any case, this phenomenon of inserting whole chapters from the Bible into one’s treatise is known only from the Bible itself. For example, David’s song in 2 Sam 22:2–51 appears as well in Psalm 18:2–50, not to speak, of course, of other parallels in Biblical literature. It does not matter where the ‘original’ position of this chapter was. Only one who lived in the ‘days of the Bible’, or thought so of himself, could have made such a plagiarism including a Biblical text in his own work.6

Lindsay noted that this statement has particular relevance for the Book of Mormon:

Now that’s fascinating. … In light of Bar-Ilan’s argument, the things Nephi and other Book of Mormon writers do with other biblical texts, such as quoting entire chapters of Isaiah or combining extensive passages of scripture from different books, widely condemned as blatant plagiarism by our critics, might actually be indicators of antiquity, not modernity.7

Conclusion

Although certainly odd when viewed from a 21st century perspective, the Book of Mormon’s frequent insertion of lengthy texts in both oral and written communication can be seen as a genuine mark of antiquity. It is also somewhat fascinating that this very feature has been used to help resolve the dating of a disputed Hebrew document. If the use of long quotes provides valuable evidence that The Words of Gad the Seer derives from earlier biblical times, the same would certainly hold true for the Book of Mormon.

Jeff Lindsay, “The Words of Gad the Seer: An Apparently Ancient Text With Intriguing Origins and Content,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 54 (2022): 147–176.

Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Book of Mormon Prophets Quote Long Passages of Scripture? (1 Nephi 19:22),” KnoWhy 473 (October 4, 2018).

Brant A. Gardner, “Literacy and Orality in the Book of Mormon,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 9 (2014): 29–85.

Deanna Draper Buck, “Internal Evidence of Widespread Literacy in the Book of Mormon,” Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel 10, no. 3 (2009): 59–74.

David B. Honey, “Ecological Nomadism versus Epic Heroism in Ether: Nibley's Works on the Jaredites,” Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 2, no. 1 (1990): 143–163.

Hugh Nibley, Lehi in the Desert/The World of the Jaredites/There Were Jaredites, The Collected Works of Hugh Nibley: Volume 5 (Salt Lake City and Provo, UT: Deseret Book and FARMS, 1988), 285–423.

- 1. See Joachim Schaper, “Hebrew Culture at the Interface Between the Written and the Oral,” in Contextualizing Israel’s Sacred Writings: Ancient Literacy, Orality, and Literary Production, ed. Brian Schmidt (Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature, 2015), 333.

- 2. Schaper, “Interface Between the Written and the Oral,” 333.

- 3. Schaper, “Interface Between the Written and the Oral,” 333.

- 4. See Schaper, “Interface Between the Written and the Oral,” 333.

- 5. Jeff Lindsay, “The Words of Gad the Seer: An Apparently Ancient Text With Intriguing Origins and Content,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 54 (2022): 147. Specifically, Bar-Ilan argues that the text derives from late antiquity, probably from near the end of the first century AD. See Meir Bar-Ilan, “The Date of The Words of Gad the Seer,” Journal of Biblical Literature 109, no. 3 (1990): 491.

- 6. Meir Bar-Ilan, “The Date of The Words of Gad the Seer,” Journal of Biblical Literature 109, no. 3 (1990): 485–486. Quoted in Lindsay, “The Words of Gad the Seer,” 149.

- 7. Lindsay, “The Words of Gad the Seer,” 149–150.