Evidence #149 | July 19, 2022

Book of Mormon Evidence: Flying Fiery Serpents

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

Abstract

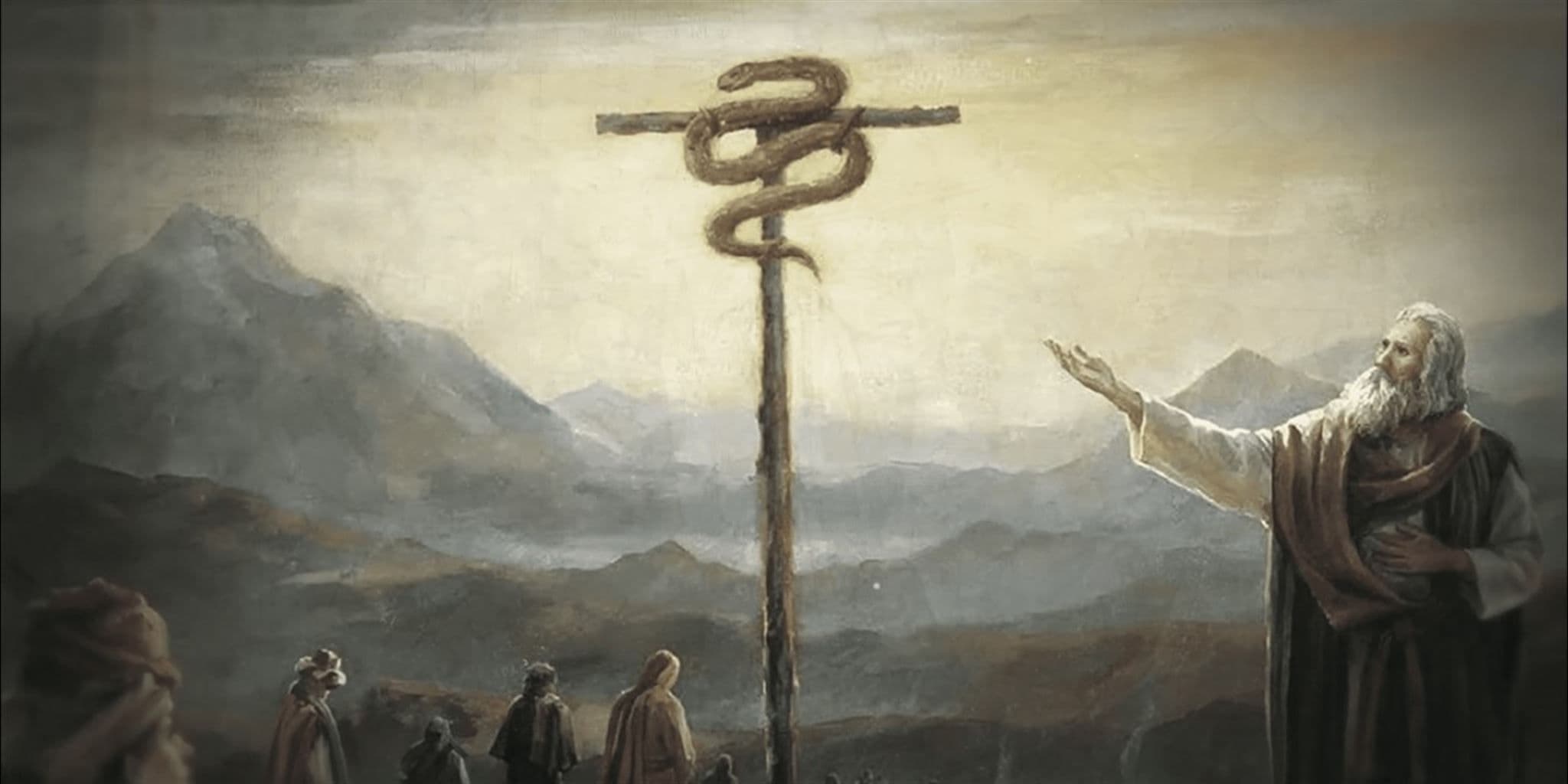

Nephi’s description of “flying fiery serpents” when recounting the brazen serpent narrative is supported by linguistic and archaeological evidence.The Bible records that on one occasion, when the Israelites murmured in the wilderness, they were subsequently bitten by “fiery serpents” (Numbers 21:4–9; Deuteronomy 8:15). When Nephi related this story to his brothers at Bountiful, he referred to them as “flying fiery serpents” (1 Nephi 17:41).1 Several lines of evidence suggest that the addition of “flying” in reference to these serpents authentically reflects ancient beliefs about venomous snakes living in the desert regions of Arabia and Sinai.

Flying Serpents in the Bible

Although the biblical accounts about the Israelites in the wilderness do not explicitly say that the serpents were “flying,” Isaiah twice mentions “fiery flying serpents” in his writings (Isaiah 14:29; 30:6). One of these is in reference to “the beasts of the south” (Isaiah 30:6), meaning the Negev desert—the very place where the Israelites were when the brazen serpent incident happened.2 This is the same region Lehi’s family traveled through when fleeing Jerusalem (1 Nephi 2).

The Hebrew expression translated “fiery flying serpents” (śrp mʿpp) in these Isaiah passages uses the same word that Numbers and Deuteronomy use to refer to “fiery serpents”: seraph (plural seraphim). This is also the word used in Isaiah 6 to describe the fiery, winged beings protecting the throne of God (Isaiah 6:2, 6). Thus, many scholars believe that the seraphim of Isaiah’s vision were winged, serpent-like creatures.3

Since Isaiah’s vision was set in the heavenly temple, some scholars have argued that its imagery reflects the physical realities of the temple in Jerusalem.4 If this is true, the seraphim mentioned by Isaiah would correlate with the brazen serpent (referred to as a seraph in Numbers 21:8) which was most likely kept in the temple prior to being destroyed by Hezekiah (see 2 Kings 18:4).5

This has led some scholars to conclude that the brazen serpent itself likely had wings,6 and that the seraph-serpents encountered by the Israelites in the wilderness were remembered as being winged or flying serpents. For instance, Moshe Weinfeld has translated the reference to seraph-serpents in Deuteronomy 8:15 (where Moses is recapping the dangers the Israelites faced in the wilderness) as “flying serpents.”7 Similarly, James Charlesworth defined seraphim as “winged-serpents” or “fiery winged-serpents.”8

Archaeological Evidence

Winged serpents are commonly depicted on ancient Egyptian artifacts. Perhaps the most famous example is the golden throne found in Tutankhamun’s tomb, with “armrests … in the form of winged serpents.”9 Egyptian shrines or throne rooms were often decorated with rows of winged cobras above the throne to protect the king or god. Winged cobras have also been found on Egyptian scarabs from the early first millennium BC.10 The fact that Nephi was writing in an Egyptian script (1 Nephi 1:2) suggests that his family may have been familiar with other aspects of Egyptian culture and tradition, such as its use of winged-serpent symbolism.

Winged serpents are associated with royal symbolism in Israel and Judah as well.11 For example, winged serpents were carved into ivories from a 9th century BC palace in Samaria (capital of the northern kingdom),12 and Israelite bronze bowls depict a royal/divine symbol flanked on each side by a winged serpent.13

Most frequently, winged serpents were depicted on Israelite and Judahite seals from the 8th and early 7th centuries BC.14 One noteworthy example is a stamp seal with a four-winged serpent, found in a 7th century BC home on the slopes of the western hill in Jerusalem.15 This region of Jerusalem was settled by refugees from the northern Israelite tribes in the late 8th century BC,16 leading some Latter-day Saint scholars to believe that this is where Lehi and his family lived around 600 BC (cf. 1 Nephi 5:14–16; Alma 10:3).17 Most biblical scholars believe that the winged serpents depicted on these artifacts are the biblical seraph, i.e., the “fiery serpent.”18

Word Order Evidence

In the current edition of the Book of Mormon printed by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1 Nephi 17:41 uses the same word order found in the King James translation of Isaiah 14:29 and 30:6: “fiery flying serpents.” As noted above, this is actually a translation of only two words in Hebrew: śrp mʿpp.

In the original manuscript of the Book of Mormon’s translation, however, the expression appears as “flying fiery serpents,” with flying coming before fiery.19 Since “fiery serpent” is the translation of a single word in the parallel expressions from Isaiah, Royal Skousen argued that the word order of the original manuscript was more faithful to the underlying Hebrew:

In the two Isaiah passages as well as the one in Numbers 21:8, there is a single Hebrew word for ‘fiery serpent’, namely śārāf, … . In the two other passages (Numbers 21:6 and Deuteronomy 8:15), the Hebrew word for ‘serpent’, naḥaš, occurs with the modifying śārāf … . Thus, in a literal translation of the Hebrew in any of these five passages, the words fiery and serpent should occur together. In the Isaiah passages, where the word for flying is added, the literal translation would thus be “flying fiery serpent”, which is the word order found in the original manuscript from 1 Nephi 17:41.20

Skousen thus concluded that “the reading of the original manuscript … follows the Hebrew construction.”21

Conclusion

Although the biblical account of the brazen serpent only mentions “fiery serpents” (Numbers 21:6, 8; Deuteronomy 8:15), the underlying Hebrew term (seraph) for these fiery serpents indicates winged creatures in other biblical contexts, and some scholars even translate seraph or its plural form seraphim as inherently referring to flying or winged serpents—something not readily apparent to someone unfamiliar with biblical Hebrew, such as Joseph Smith was in 1829.

Furthermore, the word order of “flying fiery serpent” found in the original manuscript more faithfully follows the likely underlying Hebrew expression, again suggesting a knowledge of Hebrew that Joseph Smith lacked at the time of the translation. If Joseph had merely copied this phrase from relevant passages in the King James Bible (Isaiah 14:29; 30:6), the word order would have been different.

The flying-fiery-serpent connection is reinforced by iconography from Nephi’s day that represented seraphim as winged serpents. Yet these serpent-depicting artifacts were only discovered and studied by scholars long after 1829, again making relevant knowledge inaccessible to Joseph Smith. As Neal Rappleye concluded:

This evidence strongly suggests that, whatever the actual nature of the serpents which pestered the children of Israel in the wilderness, in the 8th–7th centuries BC, seraphim (śrpym) were understood to be flying, winged serpents. … Thus, Nephi’s reference to “flying fiery serpents” reflects the common Israelite understanding of seraph-serpents at that time.22

Neal Rappleye, “Serpents of Fire and Brass: A Contextual Study of the Brazen Serpent Tradition in the Book of Mormon,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 50 (2022): 217–298.

John Gee, “Cherubim and Seraphim: Iconography in the First Jerusalem Temple,” in The Temple: Past, Present, and Future, ed. Stephen D. Ricks and Jeffrey M. Bradshaw (Orem, UT: The Interpreter Foundation; Salt Lake City: Eborn Books, 2021), 97–108.

Royal Skousen, Analysis of Textual Variants of the Book of Mormon, 2nd ed. (Provo, UT: FARMS and BYU Studies, 2017), 1:380–381.

- 1. The word order used here, with flying before fiery, follows Royal Skousen, The Book of Mormon: The Earliest Text, 2nd ed. (New Haven, CT: 2022), 54, and is based on the original manuscript (see discussion of the word order later in the evidence summary).

- 2. The Hebrew term translated as south in the KJV is negev (sometimes spelled negeb) and refers to the desert between Judah and Egypt. See Joel F. Drinkard Jr., “Negev,” in HarperCollins Bible Dictionary, rev. ed., ed. Mark Allan Powell (New York, NY: HarperOne, 2011), 694–695; Lynn Tatum, “Negeb,” in Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible, ed. David Noel Freedman (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2000), 955. See alternative translations such as the NIV, NRSV, and JPS, which make it clearer that the Negev is what is being referred to. On the children of Israel being in this area during the brazen serpent incident, see Anson F. Rainey and R. Steven Notley, The Sacred Bridge: Carta’s Atlas of the Biblical World (Jerusalem, Israel: Carta, 2006), 121.

- 3. See Karen Randolph Joines, “Winged Serpents in Isaiah’s Inaugural Vision,” Journal of Biblical Literature 86, no. 4 (1967): 410–415; Karen Randolph Joines, Serpent Symbolism in the Old Testament: A Linguistic, Archaeological, and Literary Study (Haddonfield, NJ: Haddonfield House, 1974), 42–60; T. N. D. Mettinger, “Seraphim,” in Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, 2nd ed., ed. Karel van der Toorn, Bob Becking, and Pieter W. van der Horst (Leiden: Brill; Grand Rapids MI: Eerdmans, 1999), 742–744; J. J. M. Roberts, “The Visual Elements in Isaiah’s Vision in Light of Judaean and Near Eastern Sources,” in From Babel to Babylon: Essays on Biblical History and Literature in Honour of Brian Peckham, ed. J. R. Wood, J. E. Harvey, and M. Leuchter (New York: T & T Clark, 2006), 204–210; J. J. M. Roberts, First Isaiah, a Commentary, ed. Peter Machinist (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, an imprint of Augsburg Fortress, 2015), 95–98. See also Marvin A. Sweeney, “Seraphim,” in HarperCollins Bible Dictionary, 935–936; William B. Nelson, “Seraphim,” in Eerdmans Dictionary, 1186; Matthew A. Thomas, “Serpent,” in Eerdmans Dictionary, 1188.

- 4. See Roberts, “Visual Elements in Isaiah’s Vision,” 197–212; H. G. M. Williamson, “Temple and Worship in Isaiah 6,” in Temple and Worship in Biblical Israel, ed. John Day (New York, NY: T & T Clark, 2005), 123–144.

- 5. Roberts, First Isaiah, 96, 98; Roberts, “Visual Elements in Isaiah’s Vision,” 205; Joseph Blenkinsopp, Isaiah 1–39: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (New York, NY: Doubleday, 2000), 225.

- 6. Roberts, First Isaiah, 96; Roberts, “Visual Elements in Isaiah’s Vision,” 205; Jacob Milgrom, Numbers, The JPS Torah Commentary (Philadelphia, PA: Jewish Publication Society, 2003), 174n8; James H. Charlesworth, The Good and Evil Serpent: How a Universal Symbol Became Christianized (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010), 332.

- 7. Moshe Weinfeld, Deuteronomy 1–11: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (New York, NY: Doubleday, 1991), 385, 387, 395.

- 8. Charlesworth, Good and Evil Serpent, 444–45, 602n187.

- 9. Jaromir Malek, Tutankhamun: Egyptology’s Greatest Treasure (London: SevenOaks, 2018), 146. See also Joines, “Winged Serpents,” 413.

- 10. “Scarab with Winged Uraeus (Wadjet) on Gold Hieroglyph, ca. 1070–525 BC,” Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

- 11. This is discussed in Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Nephi Say Serpents Could Fly? (1 Nephi 17:41),” KnoWhy 316 (May 22, 2017).

- 12. Joines, “Winged Serpents,” 413–414; Othmar Keel and Christoph Uehlinger, Gods, Goddesses, and Images of God in Ancient Israel, trans. Thomas H. Trapp (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1998), 251, 253 illus. 245.

- 13. R. D. Barnett, “Layard’s Nimrud Bronzes and their Inscriptions,” Eretz-Israel: Archaeological, Historical, and Geographical Studies 8 (1967): 3* fig. 2; J. J. M. Roberts, “The Rod that Smote Philistia: Isaiah 14:28–32,” in Literature as Politics, Politics as Literature: Essays on the Ancient Near East in Honor of Peter Machinist, ed. David S. Vanderhooft and Abraham Winitzer (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2013), 393 fig. 1b. See also Roberts, First Isaiah, 96; Roberts, “Visual Elements in Isaiah’s Vision,” 205.

- 14. Most of these seals can be seen in Nahman Avigad, rev. Benjamin Sass, Corpus of West Semitic Stamp Seals (Jerusalem: Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities; Israel Exploration Society; Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1997), nos. 11, 82, 104, 127, 194, 206, 284, 381, 385, 689. See also Benjamin Sass, “The Pre-Exilic Seals: Iconism vs. Aniconism,” in Studies in the Iconography of Northwest Semitic Inscribed Seals, ed. Benjamin Sass and Christoph Uehlinger (Gottingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht; Fribourg: University Press; 1991), 211 figs. 75–76, 215 figs. 77–81; Keel and Uehlinger, Gods, Goddesses, and Images of God, 253 illus. 245–47b, 275 illus. 274a–274d; William A. Ward, “The Four-Winged Serpent on Hebrew Seals,” Rivista degli studi orientali 43, no. 2 (1968): 137 fig. 1.

- 15. Shlomit Weksler-Bdolah, Alexander Onn, Shua Kisilevitz, and Brigitte Ouahnouna, “Layers of Ancient Jerusalem,” Biblical Archaeology Review 38, no. 1 (January/February 2012): 40; Tallay Ornan, “Member in the Entourage of Yahweh: A Uraeus Seal from the Western Wall Plaza Excavations, Jerusalem,” ʿAtiqot: Journal of the Israel Department of Antiquities 72 (2012): 15–20.

- 16. K. A. Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2003), 52, 59; Mordechai Cogan, “Into Exile: From Assyrian Conquest of Israel to the Fall of Babylon,” in The Oxford History of the Biblical World, ed. Michael D. Coogan (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1998), 325; Steven L. McKenzie, “Judah, Kingdom of,” in Eerdmans Dictionary, 746; Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman, The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of its Sacred Texts (New York, NY: Touchstone, 2001), 243; Charles H. Miller, “Jerusalem,” in HarperCollins Bible Dictionary, 447.

- 17. Jeffrey R. Chadwick, “Lehi’s House at Jerusalem and the Land of his Inheritance,” in Glimpses of Lehi’s Jerusalem, ed. John W. Welch, David Rolph Seely, and Jo Ann H. Seely (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2004), 87–99, 118–124; Brant A. Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon, 6 vols. (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 1:32; Brant A. Gardner, Traditions of the Fathers: The Book of Mormon as History (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2015), 65–67.

- 18. John Gee, “Cherubim and Seraphim: Iconography in the First Jerusalem Temple,” in The Temple: Past, Present, and Future, ed. Stephen D. Ricks and Jeffrey M. Bradshaw (Orem, UT: The Interpreter Foundation; Salt Lake City: Eborn Books, 2021), 97–100, 105; Izaak J. de Hulster, “Of Angels and Iconography: Isaiah 6 and the Biblical Concept of Seraphs and Cherubs,” in Iconographic Exegesis of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament: An Introduction to Its Theory, Method, and Practice, ed. Izaak J. de Hulster, Brent A. Strawn, and Ryan P. Bonfiglio (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2015), 147–55. See also Keel and Uehlinger, Gods, Goddesses, and Images of God, 273–274.

- 19. Royal Skousen and Robin Scott Jensen, eds., Revelations and Translations, vol. 5: Original Manuscript of the Book of Mormon, The Joseph Smith Papers (Salt Lake City, UT: Church Historians Press, 2021), 113. See also Royal Skousen, ed., The Original Manuscript of the Book of Mormon: Typographical Facsimile of the Extant Text (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2001), 142, line 15. Spelling errors of the original manuscript have not been retained in the body of the text.

- 20. Royal Skousen, Analysis of Textual Variants of the Book of Mormon, 2nd ed. (Provo, UT: FARMS and BYU Studies, 2017), 1:381.

- 21. Skousen, Analysis of Textual Variants, 381.

- 22. Rappleye, “Serpents of Fire and Brass,” 220.