Evidence #33 | September 19, 2020

Book of Mormon Evidence: Egyptian Writing

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

Abstract

Ancient Israelite scribes used and adapted the Egyptian language and writing systems in various ways, according to their needs and circumstances, sometimes mixing Egyptian with Hebrew or using Egyptian to write Semitic texts. The Book of Mormon’s statements about the Nephites using Egyptian language and writing are consistent with these findings.Hebrew would have been the native language of Israelites like Nephi and Lehi who lived in Jerusalem in the late seventh century BC. Yet, at the beginning of the Book of Mormon, Nephi said he wrote his record in “the language of my father, which consists of the learning of the Jews and the language of the Egyptians” (1 Nephi 1:2; emphasis added). Later, King Benjamin said that Lehi could read the plates of brass because he had knowledge of the Egyptian language (Mosiah 1:4). And by the end of the Book of Mormon, Moroni described their written script as “reformed Egyptian,” which had been “handed down and altered by us” (Mormon 9:32). Although writing in Egyptian apparently couldn’t capture their thoughts as perfectly as Hebrew (see Mormon 9:33), the authors of the Book of Mormon nevertheless utilized the Egyptian language throughout their history.

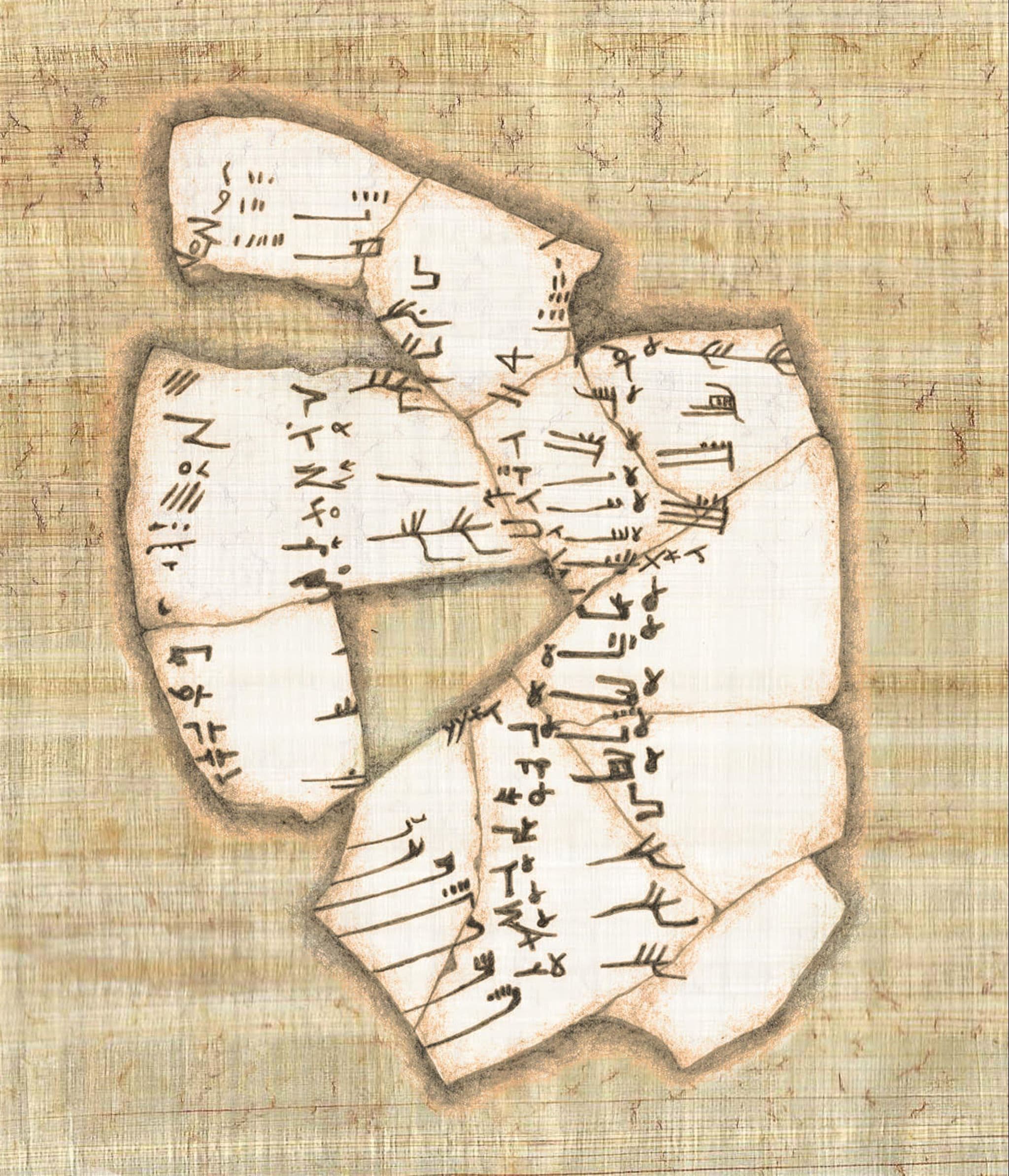

While some have viewed these claims as doubtful or unbelievable,1 evidence now demonstrates that Ancient Israelites were indeed familiar with Egyptian language and writing. More than 200 examples of Egyptian hieratic writing have been found in Israel and Judah, most dating to the eighth through early sixth centuries BC.2 Some of these texts are completely written in Egyptian hieratic,3 while others mix hieratic with Hebrew.4 Analysis of these inscriptions indicates that hieratic signs were adapted in unique ways to meet the needs of Israelite scribes,5 while also maintaining some continuity with adjustments made to hieratic writing in Egypt.6 The result was a uniquely “Judahite variety of Egyptian script” which some scholars refer to as “Palestinian hieratic.”7

Among surviving texts, the hieratic signs are generally limited to numerals, measurements, and commodities. Scholarly analysis of the texts, however, reveals subtle details which indicate that Israelite scribes had a more comprehensive understanding of the hieratic writing system.8 Judah’s status as an Egyptian vassal in the late seventh century BC, along with their continued diplomatic relationship and cultural influence, would have required Judahite scribes to have a full understanding Egyptian language and writing systems.9 Evidence for Egyptian literary influence in the Hebrew Bible makes it even more likely that Israelite scribes had comprehensive training in Egyptian.10

In addition to the texts discovered in Israel and Judah that mix hieratic with Hebrew, Israelite historical and religious texts found in Egypt were written in Aramaic using the Egyptian demotic script.11 This unexpected combination of language and script puzzled scholars for decades as they struggled to decipher the text.12 Even now, according to Menahem Kister, some parts of the writings on this papyrus “are extremely enigmatic because of the problems posed by the transcription of the Aramaic texts into Demotic script: one Demotic sign is equivalent to several Aramaic letters.”13

Conclusion

Altogether, the evidence from antiquity indicates that Israelite scribes from various times and places were familiar with the Egyptian language and writing systems, and that they used Egyptian in their own writing practices. Yet, although they used Egyptian writing and language, they followed their own Israelite scribal tradition,14 and adapted Egyptian writing systems to meet their own needs. Furthermore, Egyptian script could only imperfectly capture their Semitic texts. The little we know about the Nephites’ use of Egyptian language and writing is consistent with these findings.

Book of Mormon Central, “Why Did Mormon and Moroni Write in Reformed Egyptian? (Mormon 9:32),” KnoWhy 513 (May 2, 2019).

Book of Mormon Central, “Did Ancient Israelites Write in Egyptian? (1 Nephi 1:2),” KnoWhy 4 (January 4, 2016).

Neal Rappleye, “Learning Nephi’s Language: Creating a Context for 1 Nephi 1:2,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 16 (2015): 151–159.

William J. Hamblin, “Reformed Egyptian,” FARMS Review 19, no. 1 (2007): 31–35.

John A. Tvedtnes and Stephen D. Ricks, “Jewish and Other Semitic Texts Written in Egyptian Characters,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 5, no. 2 (1996): 156–163.

- 1. See Gimel, “Book of Mormon,” The Christian Watchman (Boston) 12/40 (October 7, 1831): “The plates were inscribed in the language of the Egyptians, see page 5. As Nephi was a descendant from Joseph, probably Smith would have us understand, that the Egyptian language was retained in the family of Joseph; of this, however, we have no evidence.” La Roy Sunderland, “Mormonism,” Zion’s Watchman (New York) 3/7 (February 17, 1838): “On p. 16 they say that the ‘records’ about which this book contains so much, were written in ‘the language of our fathers.’ Now, the language of Jacob and all his descendants, was Hebrew, but we have before shown, that the language in which this book professes to have been written, was ‘reformed Egyptian,’ a language which no person ever spake since the world was made.”

- 2. Stefan Wimmer, Palästiniches Hieratisch: Die Zahl- und Sonderzeichen in der althebräishen Schrift (Wiesbaden: Harraossowitz, 2008), 20.

- 3. Shlomo Yeivin, “A Hieratic Ostracon from Tel Arad,” Israel Exploration Journal 16, no. 3 (1966): 153–159; Orly Goldwasser, “An Egyptian Scribe from Lachish and the Hieratic Tradition of the Hebrew Kingdoms,” Tel Aviv: Journal of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University 18 (1991): 248–253.

- 4. Yohanan Aharoni, “The Use of Hieratic Numerals in Hebrew Ostraca and the Shekel Weights,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 184 (1966): 13–19; Shlomo Yeivin, “An Ostracon from Tel Arad Exhibiting a Combination of Two Scripts,” Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 55 (1969): 98–102; A. F. Rainey, “A Hebrew ‘Receipt’ from Arad,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 202 (1971): 23–30. See also John A. Tvedtnes, “Linguistic Implications of the Tel Arad Ostraca,” Newsletter and Proceedings of the SEHA 127 (1971): 1–5; John A. Tvedtnes and Stephen D. Ricks, “Jewish and Other Semitic Texts Written in Egyptian Characters,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 5, no. 2 (1996): 159, 161–163.

- 5. David Calabro, “The Hieratic Scribal Tradition in Preexilic Judah,” in Evolving Egypt: Innovation, Appropriation, and Reinterpretation in Ancient Egypt, ed. Kerry Muhlestein and John Gee (Oxford, Eng.: Archaeopress, 2012), 77–85; Stefan Jakob Wimmer, “Egyptian Hieratic Writing in the Levant in the 1st Millennium BC,” Abgadiyat 1 (2006): 23–28; Wimmer, Palästiniches Hieratisch, 271–273.

- 6. Wimmer, Palästiniches Hieratisch, 279.

- 7. Calabro, “Hieratic Scribal Tradition,” 83 uses “Judahite variety of Egyptian script.” Palestinian Hieratic is Wimmer’s term. See Wimmer, “Egyptian Hieratic Writing,” 27; Wimmer, Palästiniches Hieratisch. Goldwasser, “Egyptian Scribe,” 251 says that hieratic in Palestine was “an idiosyncratic variation of the ‘Israelite Scribe’.”

- 8. See Calabro, “Hieratic Scribal Tradition,” 77–85. Wimmer, “Egyptian Hieratic Writing,” 26 also notes a bulla where the scribe not only used an Egyptian numeral for the year number, but replaced the usual Hebrew formula with the hieratic “year” sign “in order to demonstrate his own high education.”

- 9. Bernd U. Schipper, “Egyptian Imperialism after the New Kingdom: The 26th Dynasty and the Southern Levant,” in Egypt, Canaan and Israel: History, Imperialism, Ideology and Literature, ed. S. Bar, D. Kahn, J. J. Shirley (Boston, MA: Brill, 2011), 268–290. See also John Gee, “Egyptian Society during the Twenty-sixth Dynasty,” in Glimpses of Lehi’s Jerusalem, ed. John W. Welch, David Rolph Seely, and Jo Ann H. Seely (Provo, UT: FARMS, 2004), 278–298; John S. Thompson, “Lehi and Egypt,” in Glimpses of Lehi’s Jerusalem, 259–276.

- 10. James K. Hoffmeier, “Some Thoughts on Genesis 1 & 2 and Egyptian Cosmology,” Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Studies 15 (1983): 39–49; John Strange, “Some Notes on Biblical and Egyptian Theology,” in Egypt, Israel, and the Ancient Mediterranean World: Studies in Honor of Donald B. Redford, ed. Gary Knoppers and Antoine Hirsch (Boston, MA: Brill, 2004), 345–358; Gordon H. Johnston, “Genesis 1 and Ancient Egyptian Creation Myths,” Bibliotheca Sacra 165 (2008): 178–194; Gary A. Rendsburg, “Moses as Equal to Pharaoh,” in Text, Artifact, and Image: Revealing Ancient Israelite Religion, ed. Gary Beckman and Theodore J. Lewis (Providence, RI: Brown Judaic Studies, 2010), 201–219; Bernd U. Schipper, “Egyptian Backgrounds to the Psalms,” in The Oxford Handbook of the Psalms, ed. William P. Brown (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2014), 57–75; Nili Shupak, “The Contribution of Egyptian Wisdom to the Study of Biblical Wisdom Literature,” in Was There a Wisdom Tradition? New Prospects in Israelite Wisdom Studies, ed. Mark R. Sneed (Alanta, GA: SBL Press, 2015), 265–303.

- 11. See Karel van der Toorn, “Egyptian Papyrus Sheds New Light on Jewish History,” Biblical Archaeology Review 44, no. 4 (2018): 32–39, 66, 68. The Papyrus in question (P. Amhurst 63) has a total of 35 Israelite, Syrian, and Babylonian texts, all written in Aramaic using demotic script. The papyrus dates to the mid-fourth century BC, but the texts are much older (some as old as the eighth century BC), and a corpus was put together in the late seventh or early sixth century BC. It is uncertain when the text was first transcribed in demotic. See also Tvedtnes and Ricks, “Jewish and Other Semitic Texts,” 159–160.

- 12. See Raymond Bowman, “An Aramaic Religious Text in Demotic Script,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 3, no. 4 (1944): 219–231.

- 13. Menahem Kister, “Psalm 20 and Papyrus Amherst 63: A Window to the Dynamic Nature of Poetic Texts,” Vetus Testamentum (2019): 2; doi:10.1163/15685330-12341400. See also Karel van der Toorn, “Psalm 20 and Amherst Papyrus 63, XII, 11–19: A Case Study of a Text in Transit,” in Le-ma‘an Ziony: Essays in Honor of Ziony Zevit, ed. Frederick E. Greenspahn and Gary A. Rendsburg (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2016), 248.

- 14. This may be what is meant by “learning of the Jews.” See Neal Rappleye, “Learning Nephi’s Language: Creating a Context for 1 Nephi 1:2,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 16 (2015): 151–159.