Evidence #157 | March 1, 2021

Book of Mormon Evidence: Concept of Satan

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

Abstract

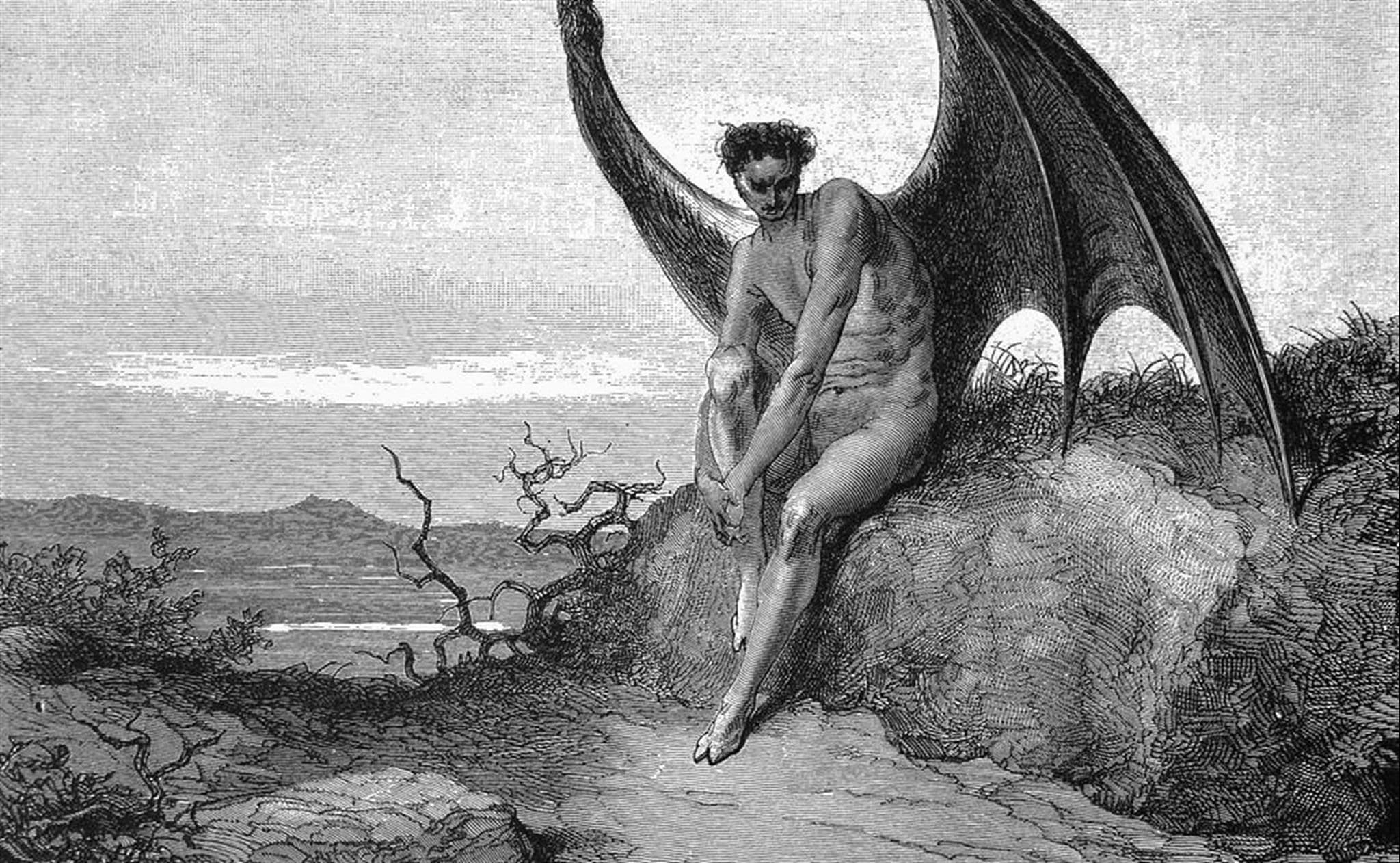

Lehi’s description of a source discussing Satan’s origins is consistent with biblical passages and related ancient Near Eastern mythology.When teaching his sons, Lehi declared, “And I, Lehi, according to the things which I have read, must needs suppose that an angel of God, according to that which is written, had fallen from heaven; wherefore, he became a devil, having sought that which was evil before God” (2 Nephi 2:17). Some have wondered how the Book of Mormon has such a vivid depiction of Satan and his origins, while the Old Testament appears to lack a concrete conception of him.1

While it is true that Satan (or “the satan”) appears in such passages as Numbers 22, Job 1–2, Zechariah 3, and 1 Chronicles 21, biblical scholars have questioned whether this figure is necessarily an evil supernatural entity opposed to God, and, if so, how his identity and function originated and evolved over time in ancient Israelite religion.2

As explained by biblical scholar G. J. Riley, “In the Hebrew Bible, one finds the concept of the ‘adversary’ (Heb. śāṭān) in two senses: that of any (usually human) opponent, and that of Satan, the Devil, the opponent of the righteous.”3 That śāṭān in Hebrew can refer to both mortal and supernatural adversaries (who may or may not always necessarily be evil) has led to conflicting interpretations of the Old Testament passages in which he appears.

Despite this ambiguity, there exist underlying conceptions from ancient Near Eastern mythology that may help clarify Satan’s identity in at least some biblical passages. According to Riley,

The Biblical idea that God and the righteous angels confronted the opposition of a great spiritual enemy, the Devil backed by the army of the demons, had a long history and development in the ancient world. Very old stories of conflict among the gods are found in each of the cultures which influenced the Biblical tradition, and these stories … contributed to the concept of the Devil.4

Riley specifically points to Mesopotamian and Canaanite myths that feature a head deity fighting back the forces of chaos, death, and evil as underlying elements in the biblical depiction of Yahweh fighting against “terrifying but legitimate spirits of calamity, disease, and death.”5 Thus, based on scriptural evidence, it appears that ancient Israelites indeed possessed an understanding of demons or other evil entities that opposed God.6 They likewise understood God as combatting sea monsters and waters that personified chaos and destruction.7 In later biblical writings, the chaos monster, “the great dragon” or “old serpent,” would come to be explicitly identified as Satan (Revelation 12:1–11).

While Lehi may have been referring to material not available in the Hebrew Bible, he might have specifically had this passage from Isaiah in mind: “How art thou fallen from heaven, O Lucifer, son of the morning! Art thou cut down to the ground, which did weaken the nations!” (Isaiah 14:12; cf. 2 Nephi 24:12).

The name rendered as “Lucifer” (Latin for “light-bearer”) in the Hebrew text is Helel ben Shachar (hēylēl ben šāḥar) and literally means “shining one, son of dawn.” This links him with “a Canaanite myth of the gods Helel and Shahar … who fall from heaven as a result of rebellion” (cf. Genesis 6:1–4),8 as well as a deity from the ancient Near East identified as “a star in the constellation … associated with Ištar and through which passes Venus” (cf. Job 38:6–7).9

As one scholar has explained, Lehi “would need to have a biblical text that described a fallen angel. Such a view appears in Isaiah 14. This biblical passage is a lament, mocking the death of the Assyrian king from the time of Isaiah.”10 The verse’s immediate setting, however, isn’t the only relevant context. “Even though this text refers directly to an Assyrian monarch who tried to make himself a divine being like the most High God, the taunt is based upon an ancient Canaanite motif of a literal divinity who tried to ascend to the throne of El, the highest god in the divine assembly.”11

In the words of John A. Tvedtnes, “Lucifer’s attempt to sit on the holy mountain reflects his desire to become part of the heavenly council.”12 Or, as expressed by another biblical scholar, Lucifer tried to “sit enthroned on the mountain where the assembly of gods met … in effect as the king of the gods.”13 For his presumption, Lucifer, perhaps the mythological personification of the Assyrian king Sargon II (circa 722–705 BC),14 was cast down to the underworld, where he was to be stripped of his power and prestige, mocked by those he once oppressed, and ultimately defeated by Jehovah (Yahweh) (Isaiah 14:15–23; 2 Nephi 24:15–23).

Conclusion

While it is ultimately uncertain where Lehi obtained his knowledge of Satan, the brief account he provides in 2 Nephi 2 is not inconsistent with the Hebrew Bible and broader Near Eastern traditions. Some biblical passages, such as those found in Isaiah 14, could very well have been the primary source to which Lehi was referring. It is also possible that the Brass Plates contained information about Satan that isn’t found in the current Hebrew Bible, such as the Satan narrative recorded in the Book of Moses.15 Whatever the precise channel of transmission may have been, it should be recognized that the Book of Mormon’s basic conceptual framework regarding Satan’s role and identity stretch deep into Israel’s past while also converging with its surrounding Near Eastern mythology.

David Bokovoy, Authoring the Old Testament: Genesis–Deuteronomy (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2014), 207–211.

John A. Tvedtnes, The Most Correct Book: Insights from a Book of Mormon Scholar (Springville, UT: Horizon Publishers, 2003), 132–153.

Clyde James Williams, “Satan,” in Book of Mormon Reference Companion, ed. Dennis L. Largey (Salt Lake City, UT: Deseret Book, 2003), 701.

- 1. See, for instance, the comments by Blake Ostler, who argued that the strong presence of Satan in the Book of Mormon is a theological “expansion” by Joseph Smith as the inspired translator of the text. Blake Ostler, “The Book of Mormon as a Modern Expansion of an Ancient Source,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 20, no. 1 (1987): 85–87.

- 2. See, generally, Peggy L. Day, An Adversary in Heaven: śāṭān in the Hebrew Bible, Harvard Semitic Monographs 43 (Atlanta, GA: Scholar’s Press, 1988); C. Breytenbach and P. L. Day, “Satan,” in Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, ed. Karel Van Der Toorn, Bob Becking, and Pieter W. Van Der Horst (Leiden: Brill, 1999), 726–732.

- 3. G. J. Riley, “Devil,” in Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, 247.

- 4. Riley, “Devil,” 244.

- 5. Riley, “Devil,” 245.

- 6. See NRSV Leviticus 16:8; 17:7; Deuteronomy 32:17; Psalm 106:37–38; Isaiah 13:21; 34:14. See also the commentary by G. J. Riley, “Demon,” in Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, 235–240.

- 7. See NRSV Psalm 74:12–17; 89:9–12; 93:3-4; Job 26:12–13; Isaiah 27:1; 51:9–10. See also, Stephen O. Smoot, “Council, Chaos, and Creation in the Book of Abraham,” Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture 22, no. 2 (2013): 31–34.

- 8. Joseph Blenkinsopp, “Isaiah,” in The New Oxford Annotated Bible, 3rd ed., ed. Michael D. Coogan (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2001), 999. One thinks also in this instance of the angels who were said, in the Enoch literature (1 Enoch 6–11), to have fallen from heaven. See Christopher Rowland, The Open Heaven: A Study of Apocalyptic in Judaism and Early Christianity (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 1982), 93; P. W. Coxon, “Nephilim,” in Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, 618–620.

- 9. J. J. M. Roberts, First Isaiah: A Commentary, Hermeneia: A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2015), 209.

- 10. David Bokovoy, Authoring the Old Testament: Genesis–Deuteronomy (Salt Lake City, UT: Greg Kofford Books, 2014), 209.

- 11. Bokovoy, Authoring the Old Testament, 209.

- 12. John A. Tvedtnes, The Most Correct Book: Insights from a Book of Mormon Scholar (Springville, UT: Horizon Publishers, 2003), 152.

- 13. Roberts, First Isaiah, 210.

- 14. Roberts, First Isaiah, 201, 207–209.

- 15. Considering that recent studies have discovered more intertextuality between these texts than originally thought, this possibility should not be discounted. See, for example, Noel Reynolds and Jeff Lindsay, “‘Strong Like Unto Moses’: The Case for Ancient Roots in the Book of Moses Based on Book of Mormon Usage of Related Content Apparently from the Brass Plates,” Presentation from Tracing Ancient Threads in the Book of Moses, September 18–19, 2020, online at interpreterfoundation.org. For examples of how other ancient Jewish texts relate to the account of Satan recorded in the Book of Moses, see Pearl of Great Price Central, “Moses Defeats Satan,” Book of Moses Essay #36, January 1, 2021, online at pearlofgreatpricecentral.org.